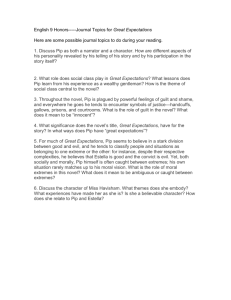

Expectations of the Average

advertisement

1 Daniel Williams Professor Ayres Composition II/British Literature II April 21st, 2003 Expectations of the Average The long battles against adversity in life cannot all be victories. In the case of Phillip “Pip” Pirrip, the protagonist of Charles Dickens’ novel, Great Expectations, this is most certainly true. A boy and a man held to so many expectations that reasoning the path to these ends proved fruitless. In the end it was only through following his honor and his heart did he truly find a place in life. The young Pip began his trials of failed expectations when he was still under the care and guidance of his older sister, Mrs. Joe Gargery. Under this regime, Pip was kept to unusually high standards of order, gentleness, and cleanliness for a child of his age. (Corrupt, 70) These charges were far greater than he could understand nor manage in the company of a poor blacksmith. It is here that Dickens first gives hint that Pip is not to be successful in meeting all of his expectations as a gentleman of humble beginnings. Pip fails in reporting the dreaded convict of the marshes and agrees to assist him in his escape. Admittedly, little else could be expected of a young, frightened boy. However, he was nonetheless kept to higher expectations and in failing this one he set in motion a chain of events that would forever after determine the fate of his later expectations. Pip, despite all the shortcomings he experienced in his early life, is an idealist. Upon meeting the beautiful, young Estella in the care of the eccentric 2 Miss Havisham, Pip becomes acutely aware of his inadequacies and sets out to better himself to become a distinguished gentleman. It is through his ideology that he remains resolute in trying to accomplish this status so he may be worthy of the affections and company of Estella. Pip begins to setup his own expectations for himself and his life after several visits at Satis House. He cleverly disguises them in his thoughts as mere hopes, but as he begins to cling to them as a road to happiness and self-worth he sees no fallacy in believing in them. The later revealed fact is that he has indeed met his expectations in his love for Estella, although for a very sinister cause. Miss Havisham’s only use for him was to serve as someone for Estella to practice her bewitching ways and observe how well she may accomplish this task. When this purpose is concluded, Miss Havisham destroys Pip’s self-imposed expectations for a time in concluding his visits and arranging his apprenticeship as a blacksmith. She recalls him only on his birthdays, apparently to offer him compensation for his previous usefulness and perhaps to further twist the knife concerning the inaccessible Estella (Craig, 1). The much forgotten convict, Magwitch, unknowingly counters this blow to Pip’s personal conjectures by increasing his social standing. This allows Pip to aspire to all the graces of wealth that his dreams had planned out for him. As his unknown benefactor specifies he is to become educated as one of high standing, he sets out with great enthusiasm to take up again his old expectations of social 3 grandeur and renews his belief that it is Miss Havisham’s will that he and Estella are to be together (1). When Pip arrives at Satis house to wish Miss Havisham farewell before he leaves for London she has discovered that Pip is no longer to be stricken to the life of a country boy laborer and she revises her expectations for the young man that she sees only as a pawn. During this meeting Miss Havisham deliberately encourages Pip’s belief that she is his patron by making it clear that she is aware of the two conditions of his fortune: the benefactor will not be named and the name Pip must be retained. The purpose of supporting Pip’s belief was to prolong his usefulness as an instrument of heartbreak towards Estella’s suitors who, would in turn, bring Pip great heartbreak as well (1). At the very beginning of Pip’s new beginning as a gentleman of wealth, we catch some foreshadowing of his poor management of his new position by his benefactor’s lawyer (and his own guardian), Mr. Jaggers. The man of neverending criminal scrutiny against the whole of man puts forward this suggestion in toying with Pip about the money he shall need for his expenses. When Pip later requests additional funds for the leasing of furniture, Jaggers gives the impression of pleasure as he seems to be witnessing the first step towards his less than spectacular expectations for Pip. As Pip takes up residence and companionship with the son of his tutor, Herbert Pocket, Pip finds himself expending large sums of money on various social gatherings. Herbert and Pip quickly begin to amass a substantial amount of debt through one particular club known as The Finches of the Grove, which 4 Pip says he would, “have never divined, if it were not that the members should dine expensively once a fortnight...” (GE, 274) It is in this that we begin to see a quickening turn for the worst for Pip’s expectations, though he seems to have met those of Mr. Jaggers. However, Pip did make some small concession to the gallantry of friendship at this time. Despite his personal losses, Pip grew concerned with Herbert’s financial status and made plans with Mr. Jaggers’ clerk, Mr. Wemmick, to create a position in which Herbert may be employed without the knowledge of his helping hand. Perhaps this action was originally some combination of fear of losing his friend and his continued belief that, once the ultimate conditions of his fortunes are made known, he will possess a great affluence that will forever eliminate debt. Nevertheless, some measure of genuine courtesy for his friend must account for this act. Pip’s conformity and adaptation to the societies in which he his now an active member become increasingly evident in his treatment of his dear friend and brother-in-law, Joe Gargery, and his former tutor and confidant, Biddy. In his relations to these two we see a major failure in Pip’s expectations. Pip’s acquaintance with the social graces of high society London have led him to be ashamed of the country boy mentality of Joe and everyone else of the primitive social order he left behind to become a gentleman. During Joe’s visit to his residence, Pip loathes every aspect of his socially uncouth demeanor(Craig, 2). Instead of helping Joe, Pip persists in treating him in much the same manner as the least noble Mr. Pumblechook once treated 5 himself when he was boy. The result is an uncomfortable situation for them both that drives a stake between the two that further compromises Pip’s bearing on his life. This arrogance over the lives of Joe and Biddy continues after the funeral of Mrs. Joe when Pip, despite his pleas to Biddy that he will cease to demonstrate this attitude and begin regular visits with them. With the appearance of Magwitch as his benefactor, Pip’s (and the reader’s) hopes for a fairy-tale outcome to his life are partly put to end and partly reassured in a skewed form(Meditating, 4). This revelation indicates that all that Pip has reasoned to accomplish in his life was either the product of or made possible by the sketchy ventures of a former convict, or so Pip begins to regard them. Here, Pip fails to see much of the good in his “dreaded” visitor as Magwitch is only trying to effect some amount of bestowment to the order of righteousness in making a great man out of Pip. Although Pip is found on the wrong side of integrity towards Magwitch at this point he does manage to gain some sense concerning his arrangements with Miss Havisham and Estella. With the knowledge that Estella and Pip’s rival, Bentley Drummle, Pip finally relinquishes his hopes that he and Estella and appeals to valor in asking Estella, in asking Miss Havisham, that she not be married to the deplorable Drummle, and that she be married to someone more suiting her grace and beauty, someone more suited than even Pip himself, for the sake of Estella’s heart. Pip goes further to ask Miss Havisham to do some good in this world and see to it that Herbert’s may continue so that he and his wife-to-be may have the happiness she kept from Estella and himself. 6 This is the point at which we begin to see a great alteration in Pip’s attitude toward the troubles of his life. By these honor-guided and heart-felt requests, he exceeds beyond the conceptions of Miss Havisham and makes such a strong impression upon her that some change of her heart is made during his oration. This accomplishment far surpasses many of Pip’s expectations. Changing the heart of one so lost to love and joy as Miss Havisham is indeed an achievement worthy of great distinction. Pip continues his change in philosophy and softens to the true nature of his benefactor. His affection grows so strong that Pip casts away all his notions of maintaining an image ideological of London high society and resolves to standing by Magwitch, a convict, and a good man through all that may come. Taken extremely ill following his time with Magwitch after he is caught trying to leave the country, Pip and Joe are reunited. Pip contends to restore his humanity towards Biddy and Joe in an effort to redeem himself and his expectations. Affirmed in addressing life with a dignity not manufactured in the streets of London and a charity of the soul and not of the pocketbook, Pip arrives at the end of his expectations as a young man. No longer bound by his expectations, nor Estella bound to Miss Havisham’s, they too are reunited and find a new beginning. Great Expectations is a story that defines the errors of human nature that are the product of great expectations. Pip tries to achieve these expectations by looking only at the means to and end but Pip discovers through the course of his life that one cannot be the protagonist of one’s own life by personal design (Craig, 7 1). The moral carried forward to the reader is that only through remaining true to one’s heart and one’s loved ones can they realize their expectations no matter how great. 8 Works Cited Craig, Amanda. “Amanda Craig on Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations.” New Statesman 735 (2002): 51-52. CD-Rom. Microsoft, 2003. Barickman, Richard. Corrupt Relations. Columbia University Press: New York, 1982. Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. New American Library: 1961. Morgantaler, Goldie. “Meditating on the low: A Darwinian reading of Great Expectations.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 Autumn 1998: 707-721. CD-Rom. Microsoft, 2003.