Third Reading from Chavez: from Jacques Levy, Cesar Chavez

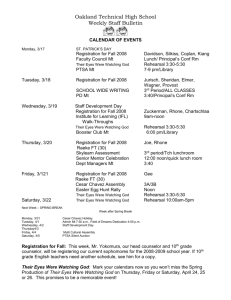

advertisement

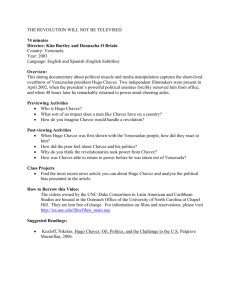

1 SI SE PUEDE – IT CAN BE DONE! A Sermon For MLK Sunday by The Rev. Wayne B. Arnason West Shore UU Church, January 20, 2008 INTRODUCTION: On this holiday weekend honoring the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. it has been traditional at West Shore Church that the service and the sermon explores some aspect of the legacy that the Dr. King’s life and the movement that he lead has left us. In a way, we are doing more than that one MLK service this year, however, because the theme that we have been exploring during January services: “Resistance” was inspired by the King holiday falling in this month. If you have been attending this series, you will remember that we have already explored through the lives of two very different historical figures the themes of Resistance through Mind and Spirit, and Resistance through Prophetic Witness. Today’s theme is Resistance Through Organizing, and next week we finish the series with Resistance Through Force. I have to say that all of these first three themes fit together like those decorative nesting Russian eggs. You cannot resist oppression or injustice in any effective way without a solid mental and spiritual foundation that accepts the suffering that resistance entails. You cannot mobilize others to support you and stand with you in resistance without a vision of a just world that can be invoked by the spoken word, by communicating and preaching what the world could be like if injustice and oppression were overcome. Rarely, however, have these two elements of resistance been enough over time to actually win victories. The third element of resistance that we recognize in today’s service is Organizing. 2 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life embodies all three of these forms of resistance to oppression and models how they work together. His spiritual foundation for the moral and political leadership he exerted is unquestioned, and his theological reflections on the spiritual foundation of his work continue to be studied by theologians and political leaders alike. King’s stature as a prophet is what most often is celebrated on this annual weekend, for unlike so many other generations who revered their prophets of the past, we continue to have King’s presence both in living memory and in recorded form. We can hear him preach his dream as easily as we can read it on a printed page. But Martin King was also an organizer, and we wanted to honor this dimension of his legacy on this Sunday, not through reflections on the civil rights movement he led, but by looking at the work of a great organizer in another field of organizing, the historical motherland of organizing in America, the labor movement. We chose Cesar Chavez as the biographical focus for our service today on Resistance through Organizing for some obvious reasons. Chavez is a person of color who has become for Mexican Americans and other Americans of Hispanic origins as iconic a figure for his culture as King is for African Americans. Indeed, there is an active movement to establish a national holiday honoring Chavez and there has been some success in establishing state holidays. The United Farm Workers Union that Chavez founded and organized holds a similar place in the history of Hispanic political power that the civil rights movement holds in the story of black political power. But most importantly today for us, it is appropriate to honor Cesar Chavez and study his life in this series on resistance because Chavez was inspired by the same spiritual and political leaders as Dr. King was to base his movement and his organizing on principles of non-violence, at a time and in a place 3 when non-violent resistance brought death and suffering in random ways to those who practiced it. Today’s service builds, then, on the last two. They all go together. Next week, when we look at John Brown, we will try to understand how resistance loses its way when it surrenders to the temptation of force as the only way to victory. To bring this historical service into the contemporary world of organizing and what it means to us as a congregation, I wanted to invite our friend and partner of West Shore who is a professional organizer to share our service this morning. I want to welcome Jason Lehrer, the Executive Director of Northeast Ohio Alliance for Hope, the faith based organizing network that our church supports. Jason will be offering readings today in the voice of Cesar Chavez and will be available after the service to chat informally with anyone who wants to know more about NOAH. Let’s enter into this service today, then, with an invocation of the vision of a world more fair, with all her people one, as choir offers us Andre Thomas’s “I Dream a World”. 4 Sermon Part 1 : There are enough of us in this room who saw the justice of the United Farm Workers demands, and who honored the boycotts of grapes and lettuce in 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s that we have a personal memory of how Cesar Chavez leadership affected us. But I would guess few in this room know much about his life or how he came to commit himself to the power of organizing. Cesario Chavez was born in 1927 near Yuma in the southwest corner of Arizona. He was the second of five children born to Librado Chavez and Juana Estrada. The Depression dried up the spending money that made possible the businesses Librado ran and so the couple raised their family eking out a living on the farm Librado’s father owned. By 1933, drought in Arizona dried up the farm as well, and Librado had to move his family to the barrio on the edge of Oxnard, California. But when Oxnard’s harvest ended, the family had no choice but to uproot and follow the harvest. At the age of eleven, Cesar first began to know the life that would define his mission : the life of the migrant farm worker. In 1935 President Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act, which gave workers the right to form unions and hold strikes. But there was a thirteen word catch in that law: “ the term ‘employee’ shall not include any individual employed as an agricultural laborer. “ Farm laborers had to fight for the same rights as other workers for years afterwards. Eventually different unions among different kinds of agricultural workers came into being, but their effectiveness was hampered by the intentional importation of thousands of braceros, undocumented temporary Mexican workers that the government let in to meet the growers complaints that their Mexican Americans were leaving them for other jobs with better conditions during and after World War 11. 5 Chavez was first exposed to labor unions through his father’s memberships in them. When his father was injured, Cesar had to drop out of high school to help feed the family and he never went back. He was in the Navy during the War, and when he came back he fell in love with the girl he had dated when the family was based in the grape growing town of Delano. In 1948, Cesar Chavez and Heleb Fabela were married. The year before, Congress had passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which limited the power of labor unions to sign up all the workers in a company, and which required unions to give sixty days notice before striking. Cesar Chavez was a union member, but it was an ineffective force when it came to improving the dismal conditions under which farm workers labored. In 1952 two white men who would become lifelong friends and inspirations to Cesar Chavez came into this life . The Chavez family by then had four of what would be eight children, and they were living in barrio called Sal Si Puede near San Jose. The name translates to “Get Out if You Can”. The first man was a priest, Father Donald McDonnell, who encouraged Chavez to work with him on farm workers rights end encouraged him to begin to read about the movement, and to read books by an Indian leader named Mohandas Gandhi. The second man was Fred Ross, a community organized working for a project of the Industrial Areas Foundation, the network founded by Saul Alinsky that is the prototype for all the faith-based organizing networks active today. Fred Ross was trying to create a Community Service Organization (a CSO) in San Jose, and he was looking for leaders, and people told him about Cesar Chavez. Chavez passion for justice, and his new exposure to theories and practice of non-violence, now 6 came together with the mentoring of a man who knew the power of organizing. The combination would be profoundly important to shaping the rest of Chavez’ life. As a CSO organizer, Cesar Chavez learned about voter registration drives, house meetings, and door to door calling. It was not easy for him. He was a shy man. Although he learned to speak in public, it was not his strength. He was fortunate to meet and make common cause with other equally passionate leaders like Dolores Huerta, who was a firebrand compared to Chavez steady light. Chavez worked on various organizing projects as paid staffer for the CSO, but his original reason for getting involved was to form a real farmworkers union, controlled not by the big unions back east, but by the local workers themselves. Chavez had some success cooperating with the Packing Workers Union, and was promoted to general director of CSO in 1958. With McDonnell, Huerta and others they helped create the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, but AWOC found that it had to fight not only the growers, but another union, the Teamsters, a freight handlers union that was competing with them for workers and was willing to let growers continue to use braceros. I’ll let Jason Lehrer and Nancy Mayer-Emerick tell you what happened next in Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta’s own words as found in Jacques Levy’s autobiographical memoir : 7 FIRST READING FROM CESAR CHAVEZ: Cesar Chavez: (Jason) I stayed in the Community Service Organization director a couple more years, hoping I could persuade the Board to organize farm workers. I thought I could do it alone, but I was discouraged by some friends, mostly some of the priests that I worked with. They said I couldn’t start a union without the help of the AFL-CIO… I didn’t know that they knew less about it than I did. When I met with the priests and Dolores Huerta, only Dolores encouraged me. Dolores Huerta (Nancy): Only three months before, we had a CSO Board meeting with Saul Alinsky just before our own convention. Cesar wanted the CSO to organize farm workers. He told the Board: “If CSO doesn’t go for this farm labor project,. I’m going to leave the organization.” It was quite obvious to us even then that the AFL-CIO wasn’t going to succeed in their drive. Then Alinsky said: “ If the CSO will have to die so that a union for farm workers can be built, it will be a very healthy death. Sometimes an organization has to die.” The board agreed to back Cesar’s project. But later, when the vote came at the convention, we were defeated. They said CSO was not a labor organization, it was a civic organization. We were all so sad. As the convention ended, (Cesar) got up and said: “I have an announcement to make. I resign.” Cesar Chavez (Jason): I stayed with CSO for two weeks after the convention, and then I quit on March 31, my thirty-firth birthday. I heard people say that because I was thirty-five, I was worried I hadn’t done much in my life.. But I wasn’t worried. I didn’t even consider thirty-five to be old. I didn’t care about that. I just knew we needed a Union. What I didn’t know is that we would go through hell in the beginning years. There would be lots of frustrations, lots of doubts, and tremendous challenges. What I didn’t know is that we would go through hell because it was all but an impossible task. Wayne announces a hymn at this point “Step By Step”. SECOND READING FROM CESAR CHAVEZ: “It is not good enough to know why we are oppressed and by whom. We must join the struggle for what is right and just. Jesus does not promise that it will be an easy way to live life, and His own life certainly points in a hard direction; but it does promise that we will be “satisfied” (not stuffed; but satisfied). He promises that by giving life we will find life – full, meaningful life as God meant it. Jesus life and words are a challenge at the same time they are Good News. They are a challenge to those of us poor and oppressed. By His life he is calling us to give ourselves to others, to sacrifice for those who suffer, to share our lives with our brothers and sisters who are also oppressed. He is calling us to “hunger and thirst after justice” in the same way that we hunger and thirst after food and water: that is, by putting our yearning into practice.” 8 SERMON PART 2: Spiritual Foundations for Organizing The story of the best known parts of Cesar Chavez life will not be told today, because we won’t have time. I wanted you most to know where he came from and what sustained him. It was certainly not money. When he resigned from the CSO to start a Farm Workers Union on his own, he worked the first three years in the field by day and did his organizing work at night. Over that time, he held public meetings, debuted the black eagle logo, created the slogan “Viva La Causa”, recruited a thousand members, and started fifty chapters. In 1964 he finally got a break when the federal government ended the bracero workers program. Their farm workers’ first successful strike leading to a boycott of Schenley Wines began in 1965. It was marked by violence against picketers and arrests. Under Chavez leadership there was no retaliatory violence from the strikers. La Causa got the attention and support of the United Auto Workers President Walter Reuther, and in March 1966 Senator Robert F. Kennedy became the first national politician to endorse the farm workers’ strike and boycott. Chavez’ hard work and leadership had made the union possible, but there is no doubt in my mind that Chavez’s Roman Catholic faith provided him a spiritual foundation. It was a faith that went beyond doctrinal Catholicism, that embraced service and accepted suffering as the conditions under which justice could be achieved. It was faith would be severely tested when the violence the union faced in future strikes made its members want to respond in kind. Inspired by Gandhi, Chavez turned to a tactic that initially he would use to reign in his own members by putting his own life on the line through a hunger strike. Three times in his career, Chavez undertook hunger strikes of four to six weeks as the ultimate spiritual and physical gesture he could make for the 9 cause. We are grateful to the UFW for this video about Cesar’s fasts, as described by Dolores Huertam his children and his friends. (Video from UFW) Third Reading from Cesar Chavez: from Jacques Levy, Cesar Chavez “At a public meeting, when Chavez asked for volunteers to go door to door to talk to workers about the union, one man stood up and said: “It’s a great idea , Mr. Chavez. The only trouble, it just won’t work. The growers are too powerful”. Most of the others began to nod solemnly. “I think that’s where we make our mistake” (Chavez) began gently, “making ourselves believe that the growers are more powerful than they really are. It’s true, they’re powerful all right, but if the movement fails, it won’t be because the growers are powerful enough to stop it, but because the workers refuse to use their power to make it go.” Sermon Part 3 : The Romance and the Reality of Organizing What little I know first hand, and from study about organizing, tells me that it is the form of resistance that requires the most patience, the longest commitment, and the greatest spiritual depth to truly be successful. That’s why so few people can make a career of it, and why so few people can be judged by conventional standards to be successful at it. Cesar Chavez is one of the great labor leaders of this century, and yet the story of the United Farm Workers under his leadership is hardly one of one victory after another. On the contrary, despite the national attention the movement received, despite the ability to successfully negotiate contracts, the union met setbacks and defeats at the hands of the growers, the Teamsters, and the courts. Lest you think I am overly romantic about the labor movement, I need to say that one of the most tragic aspects of the Cesar Chavez story is the degree to which organizing rivalries within organized labor and among unions were among his most difficult 10 challenges. Organized labor is hardly exempt from egotism, demagoguery, and particularly racism. Organizing is about power, and power has a tendency to corrupt leadership. Chavez had his critics in his later years leading the UFW, who found him stubborn and protective of his own role and style of leadership. His moral and spiritual integrity, however, was never questioned, which is what made it possible for his fasts to make a difference and for his leadership to continue. Resistance through organizing means first organizing people, and second, organizing money. In our own small efforts here at West Shore to be connected to the community organizing effort represented by the Northeast Ohio Action for Hope, we have also had to come to grips with another reality of organizing -- that people are willing to be organized and money will flow because of self-interest first, and high ideals second. Despite the high moral and ethical ground the United Farm Workers have managed to defend over the years, let’s not forget that this was and is primarily a struggle for healthy working conditions and better pay their labor. Over the six years that I have been involved with NOAH, the issues we have engaged with that has captured the imaginations of people here at West Shore have been ones where out self-interest is at stake: suburban sprawl and transportation, predatory mortgage lending practices, and our unconstitutional education funding system here in Ohio. But as NOAH has turned its focus more from these state level issues to grass roots organizing in the poorest community in Northeast Ohio, East Cleveland, our ability to directly engage with their work as a congregation has diminished. We understand intellectually that we are one region and that we have a stake in what happens in East Cleveland, but it is hard to 11 translate that into much else that funding support for NOAH and a few of us showing up when there is a call for support for a public meeting. The Unitarian Universalist churches that have had the greatest engagement and success with their faith based organizing relationships are ones that are urban or who have a different relationship to the urban core of their city than we do. Nevertheless, we will continue as a church to be a part of NOAH, and to participate as we can, through showing up at events, through fund-raising, and through whatever support is asked by the community leaders in East Cleveland whose lives we are touching. We will keep doing this because we understand that this kind of resistance to injustice, to poverty, and to oppression is critical work for a church like ours to own. We don’t hold up a leader like Cesar Chavez or Martin Luther King in a Sunday sermon in church because we are gathered here to do political work. We hold them up because in the free church tradition we have always understand that our religious lives inevitably call us towards political involvement, and because men like these exemplify the kind of embodied spiritual leadership that we trust and encourage. Both men, King and Chavez, rooted in their own religious traditions, never questioned the secular basis and religious neutrality of our civil society, embraced people of all beliefs and no beliefs, and never used their power or reputation to say that the religious faith that was so important to each of them should be the only one that should dominate our national consciousness or identity. We hold up King and Chavez today not only as icons of resistance but as the true example of religiously based political leaders that should be guiding us as we start the journey through this Presidential campaign season. May it be so.