FM: 2003

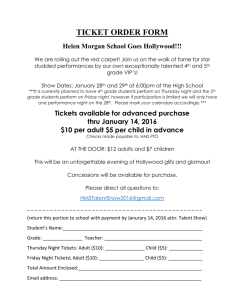

advertisement