Hermione Granger - cowles-english10-2011

advertisement

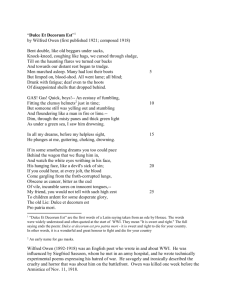

Hermione Granger Year Ten IGCSE English Ms. Cowles December 1st, 2011 Images of the Anti-Hero in Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce Et Decorum Est” Wilfred Owen’s poem “Dulce Et Decorum Est” is one of the most well-known poems to come out of the first World War because of its anti-war message. Owen’s use of intense, violent imagery does not glorify the act of war or elevate the war hero; instead, it dispels the myth that war makes heroes out of the common man. By using a pattern of anti-heroic and gruesome imagery, Owen challenges the notion that it is “sweet and becoming to die for one’s country” by exposing the indignity of death and the lasting psychological effects of watching countless men die in battle. To begin, there is an ironic relationship between the title of Owen’s poem, and the pattern of anti-hero imagery throughout. For example, in the opening stanza, Owen writes, Bent double, like old beggars under sacks Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs And towards our distant rest began to trudge. Many marched asleep. Many had lost their boots But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots Of tired, outstripped Five Nines that dropped behind (lns1-8) In this stanza, Owen depicts the soldiers as haggard and lame—they take the posture of “beggars under sacks” rather than a more iconic pose of strength and fearlessness. The emphasis on the soldiers’ physicality, “knock-kneed, coughing like hags,” reveals their vulnerability; he emasculates the image of the soldier by comparing him to a lame, knock-kneed hag, thereby challenging the notion that dying in battle is beautiful, as the title of the poem suggests. The images that Owen uses to describe the tired soldiers become anti-heroic, as they do not glorify the common man as a fearless war hero, but rather suggest that war strips men of their strength and dignity. Furthermore, Owen’s gruesome imagery emphasizes the lasting psychological effects of battle. For example, Owen writes, Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling, Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time; But someone still was yelling out and stumbling, And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime . . . Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning (lns 9-16) In this second stanza Owen reinforces the soldiers’ vulnerability by using words like, “clumsily” and “fumbling,” creating an image of men who are ill prepared for battle, rather than soldiers who are in control. He suggests that this vulnerability goes beyond the physical suffering of war and becomes psychological, as the survivors are haunted in their dreams by those they lost in battle. The memory of the soldier who did not survive, “plunges at [him], guttering, choking, drowning,” suggesting that the horrors of war do not end when the battles are won, but live on indefinitely in the minds of the surviving soldiers. In addition, Owen’s poem collapses the myth of the war hero in the last line of the final stanza: “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori,” which means, “it is sweet and becoming to die for one’s country” (ln 23). By depicting men at their weakest moment, not as heroes, but as fallen men who are scared and helpless, Owen challenges the mythology surrounding war and cautions young men against believing propaganda which suggests that war will make them strong, heroic and beloved in their country. In conclusion, Owen’s poem focuses on depicting the suffering of war by using gruesome, anti-heroic imagery and by revealing the long-lasting psychological effects of surviving a battle. In the end, Owen’s message is clear: young men need to be educated about the indignities of war and to challenge the myth of the war hero which is created to lure them into combat, the affects of which they will experience long after the war is over.