Democracy and Development: A Long-Term Relationship

advertisement

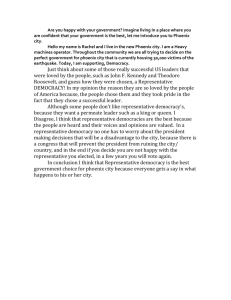

Chapter One: INTRODUCTION Does democracy promote development? Should we view regime-change as a development policy? Or should we view it as “development-neutral,” or even as a negative factor in development? What is the effect of regime type on economic growth, infrastructure, human capital, social equality, and the overall quality of life?1 Few questions in the post-Cold War era have engaged politicians and policymakers with such intensity. While democracy has always been an objective of U.S. foreign policy, perhaps at no time in our history has it been cast in such a central role. At the same time, democracy has come to be incorporated into the mission of the World Bank, the United Nations, and other development agencies. All presume that the causal effects of democracy on development are, on balance, positive. Yet the scholarly evidence for this proposition is thin. Political scientists, economists, and sociologists generally view the effect of regime type on development as inconsistent, at best. It is not clear whether democracies produce better policies and policy results than autocracies. Some argue, with an eye towards the East Asian NICs, that economic growth is most likely to be achieved through a period of strict authoritarian rule, deemed necessary to instill discipline in the labor force, to prioritize long-term savings and investment over current consumption, and to resist the rentseeking pressures of organized groups.2 Democracy is often associated with policy sclerosis3 and with skewed political representation, a situation in which relatively educated and well-organized voters (e.g., public sector unions and urban elites) are able to monopolize state resources and prevent measures to redistribute resources to the rural poor.4 Democracy may also encourage a clientelist, rent-seeking style of politicking in which side-payments to special interests trump the provision of collective goods.5 Democracy may even open the floodgates to ethnic conflict and social disorder.6 In short, there are many reasons—and a considerable amount of anecdotal evidence—to suggest that democracy does not stimulate positive development outcomes.7 Evidence for these judgments is drawn from case studies and, increasingly, from crossnational statistical studies. The latter typically focus on the relationship between regime type and economic performance. Here, the median finding is a null result. The net effect of regime type appears to be neutral or inconsistent. Scholars are somewhat more optimistic about the causal effects of democracy on social development; yet, even here there is great ambiguity. Democracies do spend more on social policies, but it is not clear that there is a robust association between Granted, development may also condition the arrival and persistence of democracy (Boix, Stokes 2003). The relationship is, quite possibly, reciprocal. However, the causes of democracy are not our concern in this study (Geddes 1999; Boix, Stokes 2003; Whitehead 2002). Naturally, we shall have to take some account of these factors in our analysis of democracy’s causal effects. 2 Amsden (1989), Chan (2002), Haggard (1990), Kohli (2004), Pempel (2002), Woo-Cumings (1999). 3 Olson (1982). 4 Lipton (1977). 5 Buchanan, Tollison, Tullock (1980), Kahn (2005). 6 Snyder (2000). 7 Hippler (1995), Leftwich (1996, 2005). 1 spending levels and policy achievements in the developing world (e.g., longer life expectancy, higher literacy, and so forth). The social policy bucket is very leaky.8 These arguments are reviewed at greater length in subsequent chapters of the book. At present, it is sufficient to observe that the scholarly view of these matters is ambivalent. While democracies may prevent certain domestic policy disasters, such as widespread famine,9 their positive accomplishments appear to be quite thin. Democracy has not proven to be associated with development, as that term is commonly understood. Of course, democracy might still be defended for other reasons, e.g., because it enhances citizen participation, civil liberties, and civil society. While these are important outcomes, it should be pointed out that this sort of argument is unlikely to inspire great enthusiasm among those currently forced to live on less than one dollar a day—roughly one fifth of the world’s population. In summarizing the results of a recent poll in eighteen Latin American countries the authors note that “the preference of citizens for democracy is relatively low; many Latin Americans value development above democracy and would even stop supporting a democratic government if it proved incapable to resolving their economic problems.”10 Indeed, the demand for “food first” sounds more sensible than the call for “democracy first.” Democracy is emphatically not equivalent to justice; it is, at best, a component of justice.11 Thus, it would be quite wrong for first-world actors to presume that a democratic organization of politics is preferable for countries in the developing world if another regime-type promises greater material reward.12 Is democracy a luxury to be enjoyed only by countries rich enough to afford it? We think not. Our reasoning hinges on a matter of conceptualization and measurement, as well as a larger theory of regime dynamics. We begin by sketching the overall argument and proceed to a discussion of possible causal mechanisms THE ARGUMENT The academic literature provides scant evidence for the proposition that democracy fosters development, as we have observed. Yet, it is notable that these empirical probes examine focus largely on the immediate or short-term causal effects of regime type. Whether a country is democratic or authoritarian today is expected to influence its developmental trajectory in the next year or decade (as defined by a given study’s research design).13 The theoretical issue is thus framed along a single dimension. Countries are classified according to their regime-status in the present or recent past. We believe that this expectation is implausible. A change in regime is unlikely to produce marked changes in the quality of governance in the immediate term. A fortiori, it is unlikely to produce marked changes in the quality of policy outcomes in the years immediately following a regime Filmer, Pritchett (1999), Ross (2005). For a general review of democracy’s effect on a host of policies see Mulligan, Gil, Sala-i-Martin (2004). 9 Dreze, Sen (1989). 10 UNDP (2004: 6). 11 Arneson (2004). Nelson’s (1980) well thought-out justification for democracy rests on its propensity (he claims) to reach just decisions, thus identifying the virtue of democracy with the larger virtue of justice. 12 See Lee Kuan Yew, quoted in The Economist, August 27, 1994, 15. 13 Among extant studies we have found only a few that approach the concept of democracy over time (e.g., Weede 1996) and none that stretches back over the course of the twentieth century. 8 2 change. Regime changes are often periods of extreme instability and unpredictability. It would be surprising, therefore, if the performance of countries moving from authoritarian to democratic rule were substantially improved during a period of transition. It is no surprise, then, that empirical tests often fail to reject the hypothesis that regime type is uncorrelated with a particular development outcome. Our contention is that the effects of political institutions are likely to unfold over time— sometimes a great deal of time—and that these temporal effects are cumulative. Regimes do not begin again, de novo, with each calendar year. Where one is today depends critically upon where one has been before. Countries build their political institutions over long periods of time. Historical work suggests that democracy and authoritarianism construct deep legacies, extending back several decades, perhaps even centuries.14 It follows that we should concern ourselves with the accumulated effect of these historical legacies, not merely their contemporary status. Thus, we introduce a second dimension – time – to our judgment of regimes. This means that, for purposes of discussion, there are four theoretically relevant ideal-types, not two: A) old authoritarian regimes, B) young authoritarian regimes, C) young democratic regimes (newly democratized countries), and D) old democratic regimes. There are also a corresponding set of transition possibilities among these four regimes, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. Our supposition is that the quality of governance increases from A to B, from B to C, and from C to D. The worstgoverned polity is an old autocracy, the best-governed polity an old democracy. 14 Collier, Collier (1991), Hite, Cesarini (2004), Linz, Stepan (1996), Mahoney (2002). 3 Figure 1.1: Regime-types in Time Democratic C D B A RegimeType Authoritarian Young Old History A=Old autocracy; B=Young autocracy; C=Young democracy; D=Old democracy. Arrows represent possible regime transitions. 4 However, in our view, both dimensions of this phenomenon are rightly conceptualized as matters of degree. The concepts “Old democracy,” “Young democracy,” et al. are therefore regarded as heuristic tools rather than discrete political entities. Indeed, there are an infinite number of regimes that fall in between these sharp categories and, equally important, there are no theoretical end-points. Hence, Figure 1.1 is constructed as a line graph, rather than a 2x2 matrix. In short, democracy is a good thing and its goodness is cumulative. The more a country has of it the better off it will be, all other things being equal. The less a country has of it the worse off it will be, ceteris paribus. These are matters of degree, hinging upon the twin components of the underlying concept. It follows that we wish to consider democracy as an accumulated stock concept rather than as a level concept, as it has traditionally been understood. We conceive of this stock as the accumulation of democratic experience over time, so it is comprised of both dimensions displayed in Figure 1.1: regime-type (a country’s degree of democracy-authoritarianism at a given point in time) and regime history (how long it has had those characteristics). The expectation is that the greater a country’s stock of democracy, the greater its “flow” of good governance. CAUSAL MECHANISMS In what ways might a country’s democratic stock contribute to its developmental potential? Why might old democracies experience improved economic development, political development, and human development relative to autocracies and young democracies? Identifying causal mechanisms is a daunting task. The theoretical variable of interest – “democracy” – encompasses a wide range of features, and the policy outcomes associated with “development” are even broader in scope, and perhaps more difficult to reach agreement on. As a result, the causal story we have to tell is necessarily quite complex. Democracy affects development through multiple channels. In this initial discussion we focus on seven causal mechanisms that we suspect have important implications across a variety of policy areas: 1) transparency, 2) civil society, 3) accountability, 4) learning, 5) equality, 6) consensus, and 7) institutionalization. (Later chapters will concentrate on causal pathways specific to particular policy areas.) These are not new concepts. Indeed, they are common elements in the usual contrast among regime-types. Democracies are often said to enjoy advantages in transparency, civil society, accountability, learning, equality, consensus, and institutionalization. Our contribution is to point out that these traditional arguments are much more persuasive if applied to established (consolidated) democracies, for the development of these distinctively democratic virtues takes time, sometimes a great deal of time. TRANSPARENCY Democracies, almost by definition, operate with a greater degree of openness than autocracies. Leaders and issues must be paraded before the electorate, institutions enjoy a degree of autonomy from each other (and are often in direct competition with each other), and the most important information-dispensing institution, the press, is comparatively free from political control 5 (freer, that is, than it would be under authoritarian rule).15 In a democracy, politics is everybody’s business. This means that the mechanisms by which political transparency might be achieved are generally much more prevalent in a democracy than in an autocracy. The basic point is not contested. What deserves emphasis, from our perspective, is that the mechanisms by which transparency becomes realized are not achieved simply by the installation of multi-party elections and constitutionally guarantees of freedom of the press. Indeed, the very goal of transparency may take time to establish as a valued good. This is especially true for countries emerging from a long period of authoritarian rule, where post-transition elected governments are likely to champion strong government, disparage the goal of openness, and be intolerant of critical views in the public sphere. In any case, it takes time for institutions that produce transparency – principally, government agencies, legislative committees, the media, the judiciary, and NGOs -- to become skilled investigators of public malfeasance and monitors of the public weal. They must first carve out their respective roles, develop constituencies, defend their independence, gain knowledge of complex issues, create knowledge networks across institutions, and develop a reputation for perspicacity and probity such that their word on a subject carries weight. CIVIL SOCIETY The creation of a strong civil society – a sphere independent from politics and from the market – is virtually impossible under circumstances of authoritarian rule. Indeed, neither the strong authoritarian state nor the weak authoritarian state can effectively guarantee the flourishing of voluntary associations. In the first instance, the institutions of the state or ruling party tend to pervade all public deliberations. In the second instance, there is no space safe for public deliberations because there is no public order. Thus, it may be argued that civil society is premised on the existence of a democratic regime.16 However, voluntary associations representing diverse purposes, interests, and ideals do not spring up immediately following the declaration of multi-party elections. In some cases, there is scarcely a semblance of civil society prior to the instauration of multi-party competition. In other cases, where such organizations are already in place, it takes some time for them to gain traction, i.e., to reach out to new constituencies and to mobilize resources. Even in well-educated and comparatively developed societies such as the former Soviet bloc the development of civil society has lagged behind the democratization process.17 Yet, over time, the density and diversity of voluntary associations seems to grow under conditions of democratic rule. Despite the decline of party organization in some longstanding We realize that sometimes freedom of the press is regarded as a core definitional trait of democracy and at other times it is seen as secondary. For our purposes, it matters little. 16 Democracy is not a necessary condition for the presence of a strong civil society, as can be seen in cases like Zimbabwe, a less than democratic state with a strong network of AIDS-related NGOs (Batsell 2005). (We are grateful to Even Lieberman on this point.) But it is likely that, all else being equal, civil society networks will be stronger in a democratic system than a non-democratic one. Note that in semiauthoritarian or semi-democratic regimes such as France and England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, civil society flourished among sectors of the populace who were granted civil liberty, namely the aristocracy. Yet, even in these instances, the right of privileged actors to project dissenting views prominently in the public arena was limited by a jealous state. Thus, civil society maintained a covert quality, quite similar to the role of the intelligentsia in semi-authoritarian regimes around the world, who are free to talk amongst themselves but dare not engage a broader public. 17 Howard (2003). 15 6 democracies, the general pattern of civil society is one of persistence and increasing diversity. In developing societies, the trend is even more marked.18 Thus, it seems fair to regard civic associations as a hallmark of established democracies. ACCOUNTABILITY Where conditions of democracy hold, we expect that mechanisms of accountability will, over time, become more established.19 In this principal-agent relationship, the principal is the electorate, composed of all citizens (we leave aside the precise definition of the citizenry), and the agent is the class of elected officials (acting through appointed members of the bureaucracy). The class of issues to which such mechanisms apply constitute the domain of the principal-agent relationship. In order for mechanisms of accountability to exist the principal must have some way to monitor the activity of the agent; otherwise, there is no connection between what the agent does, and potential punishment or reward that the principal might bestow. In order for mechanisms of accountability to be fully operative across a nation several conditions must hold: a) the agent must be identifiable and relatively coherent (otherwise, there is no person or persons to reward or punish); b) the principal must have monitoring capacity; c) the members of the class of principals must be large (a mass electorate rather than a narrow selectorate), and, most importantly; d) mechanisms by which the principal can regularly reward or punish the principal must be available. It follows that mechanisms of accountability are likely to be weak and/or limited in purview in an authoritarian regime. To be sure, there is likely to be an identifiable agent. However, this agent will be difficult to monitor because authoritarian regimes tend not to operate in an open, transparent fashion. Equally important, the class of persons with an accountability relationship to the agent is generally very small, extending perhaps to the military, an aristocracy, a landowning class, or the agent’s ethnic grouping. The “selectorate” is much smaller than the potential electorate. Of course, the citizens at the base can exact revenge upon an irresponsible leader by overthrowing him or her. But this is a crude, irregular, and generally ineffective mechanism of accountability, and operates (to the extent that it operates at all) only in the most extreme cases of malfeasance. This means that the class of issues to which mechanisms of accountability can be said to apply in a dictatorship is limited to those of concern to the selectorate and/or those which might anger the broader citizenry to the point of open revolt. In sum, accountability is not a concept with much use in a typical authoritarian regime. On this score, there is general agreement. The point we wish to stress is that the establishment of effective mechanisms of accountability in a democracy requires a good deal of time. Indeed, the immediate effect of multi-party elections is quite limited. Leaders must pay verbal homage to what the electorate wants (or thinks it wants), at least during election periods, but such rhetorical flourishes may be only that, unless and until leaders realize that they will be punished or rewarded for what they do once in office. The various facets of accountability, as defined above, generally require multiple iterations of an electoral cycle to become fully effective. We have already demonstrated that it takes time for the ideal of transparency to become realized. It also requires time for the assignment of responsibilities – e.g., between executive, legislature, and judiciary, between elective and unelective bodies, between national and subnational authorities – to become clear. Until then, there is no “agent” who can plausibly be praised or blamed for their performance. 18 19 Boone & Batsell (2001), Parker (1994), Webb (2004). For helpful discussions of the meaning of accountability see Fearon (1999) and Schedler (1999). 7 It takes time for mechanisms of “horizontal” accountability to develop.20 Most important, it takes time for electoral institutions to develop such that the electorate can exact revenge (or heap rewards) upon officeholders. The accountability relationship between elites and masses is particularly evident in the arena of economic policy for the simple reason that the fate of the economy is a high-salience issue. Here, mechanisms of electoral accountability are highly plausible.21 Perhaps the most important lesson that democratically elected elites learn is that growth performance matters for their political future. They are more likely to retain their jobs if the country prospers, and very likely to lose their jobs if it does not.22 Note that in new democracies, politicians frequently adopt short-term policies intended to pay off political supporters and stimulate the economy during election seasons.23 Short-term goals dominate because there is no assurance that elites would be able to make good on longer-term promises. However, once elites and voters have experienced a series of electoral and economic cycles, longer time horizons may prevail. Voters who have directly experienced the effects of populist economic policies are likely to be skeptical of claims that soaking the rich, inflating the economy, abrogating debt agreements, or resorting to massive expropriation of property will enhance their livelihoods.24 Indeed, various studies have shown it takes time for voters in a newly democratized country to begin to link their votes to the country’s economic performance. Economic voting appears only as the electorate develops trust in new institutions and begins to treat elected politicians as guardians of the economy.25 Consequently, leaders in established democracies may be willing to impose sacrifices over the short term to facilitate stronger growth performance over the course of their administration.26 Thus, as democratic experience accumulates we expect a slow transition away from a populist style of politics and policy-making. As a result, we expect countries with longer democratic histories to institute better policies than transitional democracies or authoritarian regimes. LEARNING Politics is not simply a product of power and interests. It is also, to some considerable extent, a product of cognition, i.e., of learning.27 As we use the term, learning refers to any cognitive development that is rational (a product of reason), true (as near as one can tell), and helpful in realizing basic values or objectives (assumed to remain fixed). For example, citizens may learn that a party or politician is corrupt, or that a party’s promises are credible (or non-credible). Politicians may learn that a particular issue is of great salience to the electorate, or that it should be framed in a particular way in order to be palatable to the electorate. And politicians and citizens may learn that one policy works better than another to achieve a given policy objective. These are all examples of O’Donnell (1999). Samuels (2004). 22 Lewis-Beck, Stegmaier (2000). 23 Dornbusch, Edwards (1991). 24 Weyland (2002). 25 Anderson, Dodd (2005), Duch (2001). 26 Stokes (2001, 2002). 27 Hall (1993), Heclo (1974), Mantzavinos (2004), Preuss (2006), Weyland (2004). 20 21 8 learning as it pertains to the political sphere.28 Over time, politicians learn to be better politicians, and citizens learn to be better citizens. Our expectation is that there are more opportunities for learning in a democratic context than in an authoritarian context. As we have already observed, policymaking processes in authoritarian regimes is usually closed (non-transparent), and is generally monopolized by a small number of elite actors – typically, a single leader and his or her coterie (though they may be assisted by a large bureaucracy).29 There is generally little turnover among the leadership cadre, and when turnover does occur, e.g., by natural death or by coup, it is usually not the sort that is propitious for policy learning. In a democracy, by contrast, opportunities for learning are much greater because the policy process is more open, the number of actors is greater (each of whom may bring a different perspective to a policy problem),30 turnover happens more frequently, and it happens in a context where new elites are able to build upon prior experience. Since learning takes time we expect its benefits to accrue over time, as democratic stock accumulates. Consider that political learning is largely experiential. Since general theories of politics and policymaking offer only the most general guidance (and few politicians pay heed to political science anyway), citizens and policymakers must learn by doing. And undoing. A new policy is tried, its effects are evaluated, and a new course of action is considered. Occasional bold experiments are followed by long periods of muddling through. Learning occurs in the political realm as new issues are trotted out before the electorate, the framing of these issues is adjusted, leaders enter and exit the political stage, and the public’s response – via elections and opinion polls – is registered. The process is time-consuming and error-prone. “Lessons” are learned only after many miscues. Not only must governing politicians learn what constitutes good policy; voters must also learn to recognize good policy. There may even be a third stage, during which politicians learn that voters have learned to distinguish good policies from bad.31 EQUALITY We have already noted the importance of mechanisms of accountability, ensuring that political elites in a democracy will be responsive to the electorate at-large (or at least a majority or plurality of that electorate). Here, we explore the possibility of an egalitarian thrust that gains its power from other aspects of a democratic constitution.32 28 In Weberian terms, learning involves instrumental rationality while deliberation involves more basic substantive rationality, where the goals themselves are called into question. The concept of deliberation covers both aspects of cognitive development. It is of course quite possible that democracies encourage not only learning but also deliberation over matters of substantive rationality. However, this claim is perhaps harder to sustain and is unnecessary, we think, to the broader argument. 29 Bueno de Mesquita et al. (2003). 30 The sheer number of decisionmakers may, by itself, enhance the quality of decision making, as suggested by recent research in social psychology (Surowiecki 2004). As yet, there have been only a few attempts to test the “wisdom of crowds” in political settings (Blinder & Morgan 2005; Lombardelli, Proudman & Talbot 2005). 31 In Sartori’s (1987: 152) words: “Elected officials seeking reelection (in a competitive setting) are conditioned, in their deciding, by the anticipation (expectation) of how electorates will react to what they decide. The rule of anticipated reactions thus provides the linkage between input and output, between the procedure . . . and its consequences.” Sartori refers to this as a “feedback theory of democracy.” 32 As will become clear, this is an institutional argument (following Schattschneider), not a cultural one (following Tocqueville). 9 Note that the formal basis of power in a democracy is votes, a fact that separates this regime-type from an autocracy, where power is based on factors such as coercion, money, loyalty, connections. Even though power in a democracy does not rest solely on votes, votes matter quite a lot. This means that every citizen has equal power while standing in the polling booth, and this central fact may prompt political elites to pay attention to those without money, status, connections, or other resources than they would in other circumstances. Second, because every citizen’s vote matters we can expect that political conflicts in a democracy may exhibit an expansionary quality. Just as the loser of a fight appeals for support from the crowd, a losing faction is likely to appeal to those who were not initially involved (or perhaps even aware) of the conflict. Thus, while most political conflicts begin in small spheres, and may be restricted to elite players, outsiders are continually being appealed to. Their participation is demanded. And this expansionary quality of conflict in a democracy promises to reach out to previously excluded groups. E.E. Schattschneider called this the contagiousness of conflict, and viewed democracy as “the greatest single instrument for the socialization of conflict.”33 For this reason, we expect that the vote-seeking dynamic of multiparty democracy will lead politicians from the losing (or minority) party to craft policy platforms that will appeal to voters who are currently excluded, or poorly served, by established parties. There is a natural affinity between an out-party and an out-group. Both are excluded. So long as the out-party is allowed to campaign freely (as even the most minimal definitions of democracy presume), leaders of that party should find their natural constituency among the discontented. While autocrats characteristically seek to limit access to the public sphere, democrats seek to expand access – registering voters, getting them to the polls, educating them on the issues, and seeking their allegiance. In this fashion, competitive multiparty democracies have successfully integrated new voters and nonvoters. Finally, it is important to note that the institutions of democracy are, in form and in spirit, egalitarian, for democracy presumes the political equality of all citizens.34 Once it is accepted that all citizens are equal members of the polity, this may engender a certain degree of cognitive dissonance if certain members of the polity are grossly mistreated (i.e., treated in a manner unbecoming of a citizen). In this way, the status of citizenship may lead to greater respect across social groups. Similarly, citizenship may serve as a template and a political fulcrum for out-groups to assert their rights within a community.35 Thus, for both normative and power-seeking reasons, we expect that democracies will do a better job of representing out-groups, and we expect that this will contribute to the social and economic empowerment of these groups, whether defined by social class, ethnicity, race, religion, language, caste, or sex. However, none of the processes that we have identified is quick and easy. Indeed, all take a good bit of time to materialize. The American civil rights movement, to take an extreme example, occurred a century and a half after the instauration of democratic rule and a century after the principle of equal suffrage was enunciated. Thus, like other mechanisms leading to better governance, we theorize that egalitarian tendencies will be most marked in old democracies and of uncertain import in new democracies, where xenophobic and parochial tendencies often hold sway. We suspect that the constitutional system of democracy helps to account for the ubiquity, and the eventual success, of campaigns for social justice undertaken by working classes, peasants, and ethnic and racial minorities in democracies around the world.36 Schattschneider (1960: 12). Beitz (1989). 35 Thompson (1963), Wilentz (1984). 36 Alvarez, Dagnino & Escobar (1998: 17), Armijo & Kearney (2007), Dominguez (1994), Myrdal (1944). 33 34 10 Few analogues can be found in the history of authoritarian states. To be sure, regimes such as the Ottoman Empire, Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and China have been quite successful in suppressing ethnic strife, at least for a period of time. Yet, authoritarian rule in these countries has not led to a popular acceptance of the principle of minority rights; nor has it led to an enhancement in the status of most minority groups. These groups have remained, for the most part, cultural outsiders. Rarely, if ever, have they been included in the process of governance. This cannot be considered a healthy outcome. It is important to keep in mind that social exclusion, while intrinsically bad, also has negative externalities. It reduces levels of trust across a society, removes large portions of society from active participation in higher education and in high-skilled sectors of the labor market, lowers the quality and reach of social service provision, and may fuel ethnic conflict at some point in the future. We are of course cognizant of the various exceptions to our argument. Thus far, democracy has not worked toward the inclusion of out-groups in Sri Lanka (with respect to the Tamils), or in Thailand (with respect to the Muslim population in the south). Similarly, there are examples of authoritarian regimes (e.g., the Ottoman Empire) and semi-authoritarian regimes (e.g., Malaysia) who successfully deter, or at least defer, ethnic conflict. Nonetheless, it is notable that these regimes have not done so through processes of inclusion. Rather, they have practiced the art of ethnic separation, a solution that rarely provides a workable long-term solution to the problem of ethnic conflict, for the principle of equal rights and equal citizenship is explicitly disavowed, or at best downplayed. CONSENSUS Over time, we expect that the operation of a democratic system will lead to greater consensus in a society. 37 This does not mean that contending ideologies will disappear.38 It means, rather, that there will be areas of agreement that stretch across the major parties and social groupings, and that such areas of disagreement as persist are unlikely to engender violent conflict. The argument for consensus is not self-evident. A large literature on democratic overload posits that democracy engenders costly and destabilizing power struggles among subgroups.39 And the literature on democratization is replete with examples of the difficulties encountered by newly democratizing countries—particularly when those countries are poor or ethnically divided or where the question of nationality is open to question.40 The problem of democratization in the modern era is enhanced by a surfeit of expectations, accumulated over many years. Citizens have been told to expect great achievements from self-government, and they generally expect these goods to materialize in a hurry. It is the fashion of political leaders during the long and dangerous struggle for democracy to overpromise, and transitions offer little preparation for the humdrum nature of everyday politics. Thus, when the transition finally occurs, it may be greeted with extravagant expectations. Almost inevitably, democracy experienced is never quite the same as democracy envisioned.41 The democratic process of give-and-take among competing priorities may seem to barter away what had initially been gained, a corruption of the democratic ideal into brokerage politics. Needless to say, such disillusionment does not augur well for political stability. In addition, democratization frequently stimulates a surge of demands on the part of previously quiescent and Dahl (1966), Eckstein (1966), Graham (1984), Horowitz (1962), Keman (1997), Lijphart (1999). Fukuyama (1992). 39 Crozier, Huntington, Watanuki (1975). 40 Chua (2003), Fein (1995), Mousseau (2001), Papaioannou, Siourounis (2004), Snyder (2000). 41 O’Donnell, Schmitter (1986). 37 38 11 perhaps even actively repressed groups. These might be lower classes, excluded ethnic or racial groups, or some other category of out-group.42 Such mobilizations from below may be destabilizing and may have negative externalities for the climate of social and economic opportunities.43 We are not making any claims about the conditions under which new democracies will survive or fail. Our point is simply that if they do survive their tumultuous youth, democratic societies are likely to experience a tempering of political conflict. Consider that the inclusionary tendencies of democratic polities (noted in the previous section) create opportunities for elite members of all sizeable social groups. These are the cadres who assume leadership positions in social movements, political parties, and perhaps even revolutionary insurrections. Once granted a taste of political power as leaders of legitimate (and legal) entities, these elites may find it in their interest to work within, and to uphold, the democratic polity. It is not just a matter of personal gain (the power and pelf they may receive from their leadership position), but also a matter of political logic; they are now in a position to bargain, to achieve real gains for their social group or political cause. Additionally, the relatively open nature of deliberation in an established democracy may diminish the appeal of conspiracy theories, which tend to flourish in the deep fog of authoritarian rule.44 It is possible to know, with a reasonable degree of certainty, who is in charge and who is responsible for a given decision. Over the long run, the open-ness of a democracy may serve as the strongest weapon against intrigue and, indeed, against any surprising political developments. Where all parties can express their views, organize freely, and where a vigilant press reports on all salient political developments, the uncertainties of politics are greatly reduced. In any case, whatever centripetal tendencies are inherent in democracy are more likely to be in evidence when those democratic arrangements have been in operation for some time. For these reasons, the thesis of democratic overload is much more compelling when applied to new democracies than when applied to old. New democracies tend to be boisterous, obstreperous affairs. Established democracies, by contrast, tend to be more restrained. In particular, the norm of incremental change is more likely to be accepted. Thus, given sufficient time and given a sufficient degree of political institutionalization, we expect that democracies will develop greater consensus than authoritarian regimes. INSTITUTIONALIZATION Many of the comparisons that we have been drawing -- between established democracies on the one hand and autocracies and recently democratized societies on the other – hinge upon a more general and abstract process known as institutionalization. Although the concept is rather difficult to define, there is little dispute over its central importance to the quality of governance. “The major role of institutions in a society is to reduce uncertainty by establishing a stable . . . structure to human interaction,” writes Douglass North.45 Political institutions thus offer a mechanism for solving society’s myriad coordination problems. What does this mean, in practical terms? How do we differentiate a well-institutionalized polity from a poorly-institutionalized polity? March and Olsen suggest the following: Eckstein (1989), Escobar, Alvarez (1992), Stepan (1989), Tarrow (1998). Haggard, Kaufman (1995: 184-6). 44 Tilly (1997). 45 North (1990: 6). 42 43 12 (1) that there are key social institutions that are viewed as existing over time, enduring through generations of individuals, and accumulating a collection of practices and rules that reflect generations of social and political experience. And . . . (2) that individuals act within the political system as trustees of those institutions, rather than as autonomous individuals. When a farmer sacrifices current crops to maintain the water table for future generations of his family, he acts as a trustee of his family. When a political official refuses to increase the public debt even though it would ameliorate immediate problems of unemployment, inequity, or injustice, he acts as trustee of the future community.46 Drawing on the passages quoted above, as well as on other works devoted to the subject, we stipulate that a well-institutionalized polity is functionally differentiated, regularized (and hence predictable), professionalized (including meritocratic methods of recruitment and promotion), rationalized (explicable, rule based, and nonarbitrary), and infused with value.47 We surmise that relatively few authoritarian regimes in the modern era are well institutionalized. Ethiopia, for example, has enjoyed sovereignty for centuries but has yet to develop a well-articulated set of governing institutions: as in most authoritarian states, power remains highly personalized and informal.48 In contrast, virtually all long-standing democracies have highly developed, highly differentiated systems of governance, involving both formal bureaucracies and extra-constitutional organizations such as interest groups, political parties, and other nongovernmental organizations. Thus, the length of time a democracy has been in existence serves as a rough indicator of its degree of institutionalization, while the length of time an authoritarian regime has been in existence may have less of a bearing on its level of institutionalization. Indeed, reversals are common, as in the latter days of the Soviet Union or in Iraq under Saddam Hussein. There are a few exceptions to this general rule, i.e., longstanding authoritarian states with highly institutionalized systems of rule such as China and Singapore, or longstanding democracies with poorly institutionalized public spheres such as Bangladesh and Papua New Guinea. But these are notable exceptions to what appears to be a strong general trend. When indicators of state capacity are regressed against a measure of democracy stock the relationship is strong and robust, as shown in Table 1.1. [Insert table showing the Kaufmann indicators regressed against democracy stock, along with the usual controls – GDPpc, urbanization, regional dummies, English colony, trade openness,…] We suspect that the reasons for this stem directly from their systems of rule. Where power is personalized, as it is in most authoritarian settings, the development of legal-bureaucratic authority is virtually impossible. In particular, leadership succession is difficult to contain within regularized procedures and promises a period of transition fraught with uncertainties. Thus, even if a monarch or dictator adheres to consistent policy objectives during his or her rule, there may be little continuity between that regime and its successor (“regime” is employed here in its broader sense). The hallmark of a long-standing democracy, by contrast, is its ability to resolve the problem of leadership succession without turmoil and without extraordinary discontinuities in policy and in political organization. The framework remains intact, and this means that the process of institutionalization may continue. March & Olsen (1995: 99-100). Huntington (1968), Levitsky (1998), March, Olsen (1995: 99-100), Polsby (1968). The concept of institutionalization has deep intellectual roots and may be traced back to work by Henry Sumner Maine, Ferdinand Tonnies, Max Weber, Emile Durkheim, and Talcott Parsons, among others (Polsby 1968: 145). 48 Marcus (2002). 46 47 13 More importantly, we suspect that the institutionalization of power leads to greater gains within a democratic setting than in an authoritarian setting. Institutionalization matters more under democracy. Consider the task of establishing social order and stability in a polity and resolving problems of coordination.49 Noninstitutionalized polities are unstable and inefficient, almost by definition, for there are no regularized procedures for reaching decisions. However, in an authoritarian setting a Hobbesian order may be established simply and efficiently by fiat and force. Rule by coercion, insofar as it is successful, can be imposed without loss of time and without negotiation; the threat of force is immediate. Consequently, there is less need for highly institutionalized procedures for reconciling differences and establishing the force of law. The sovereign may rule directly. Thus, the authoritarian transition period, during which actors accustom themselves to a new set of rules, should be fairly quick. In a democratic setting, by contrast, resolving conflict is complicated. Somehow, everyone must agree upon (or at least agree to respect) the imposition of societywide policy solutions that involve uneven costs and benefits. In order to handle these quintessentially political problems, a democratic polity has little choice but to institutionalize procedures for negotiation among rival constituencies and organizations. Establishing these procedures takes a good deal of time, and no little struggle. An electoral law, for example, is not fully institutionalized until patterns of behavior have adapted to that particular set of formal stipulations – in this case, one may judge the degree of institutionalization by the percentage of “wasted votes” and by the degree of churning among the parties. The process of adjustment always involves mutual interaction between elites and masses. One side’s behavior is contingent upon the other (and indeed, may be fully “rational” in light of the other’s suboptimal behavior). However, once a stable equilibrium becomes established, we expect it to be more effective in resolving differences and finding optimal solutions than would be fiats imposed from above. Another product of successful political institutionalization under democratic auspices is that nebulous state of grace known as the rule of law. In a state governed by the rule of law 1) laws must be general; 2) laws have to be promulgated (publicity of the law); 3) retroactivity is to be avoided, except when necessary for the correction of the legal system; 4) laws have to be clear and understandable; 5) the legal system must be free of contradictions; 6) laws cannot demand the impossible; 7) the law must be constant through time; and 8) congruence must be maintained between official action and declared rules.50 The rule of law is generally acknowledged to be a key ingredient in the establishment of secure property rights and in the achievement of credible commitment to those policies, which underpin growth in a market economy. While a limited rule of law has been successfully established in some authoritarian states, it is usually difficult to maintain and can never, by definition, bind the ultimate decision makers. With respect to the legislature, the judiciary, and other arms of government authoritarian states usually find it difficult to depersonalize political authority, a key requisite of the rule of law. In no autocracy is it possible for present-day rulers to effectively constrain decisions taken by their successors. This means that long-term credible commitment is impossible in an authoritarian setting. By contrast, the institutionalization of power in a democratic regime is closely linked to the establishment of rule of law. The same forces that rationalize channels of power also tacitly endorse the rule of law—so much so that a fully institutionalized democracy (as described above) is impossible to imagine in the absence of rule of law. While we have granted causal precedence to 49 50 Hardin (1999). Sanchez-Cuenca (2003: 68). 14 “institutionalization,” it will be seen that these two processes are so closely aligned that they are difficult to disentangle empirically. In any case, the key point is that it takes a great deal of time to establish a formal framework to create and administer the law in a new regime, to ensure compliance, and to allow for the slow diffusion of norms sanctioning this delicate arrangement. Thus, it may be argued that there are two necessary conditions for the firm establishment of the rule of law: democracy and a well-institutionalized public sphere. CONCLUSION We have argued that democracy, if maintained over time, is likely to foster transparency, civil society, accountability, learning, equality, consensus, and institutionalization. If this argument is plausible, tertiary benefits should also materialize. These might include a) greater political stability, b) longer time-horizons, c) a more credible commitment to policies (once adopted), and d) greater legitimacy accorded to political leaders and to government policies. And this, in turn, should eventuate in better governance outcomes across a wide range of policy areas. These putative interrelationships are summarized in Figure 1.2. Accordingly, we believe that the argument for a democratic “development effect” is quite plausible if one considers regime type through a historical lens. Schematically: democracy + time = development. 15 Figure 1.2: Overview of the Argument Exogeneous Cause Democracy (multi-party elections, civil liberties, broad suffrage,...) + Time Principal Causal Mechanisms Tertiary Benefits 1. Transparency 2. Civil Society 3. Accountability 4. Learning 5. Equality 6. Consensus 7. Institutionalization 1. Stability 2. Long timehorizons 3. Credible commitment 4. Legitimacy 16 Expected Policy Outcomes 1. Growth 2. Economic policy 3. Infrastructure 4. Policy continuity 5. Environmental policy 6. Education 7. Public health 8. Gender equality Of course, this is a highly schematic view of what is bound to be an extraordinarily complex set of causal relationships. Several of these complexities deserve notice (each will be discussed at greater length in the following chapters). First, the key theoretical variable of interest -- “democracy” -- is exceedingly difficult to define. In our view, minimalist democracy (multi-party competition) is good for development, but the deepening of democracy (including, e.g., civil liberties and multiple avenues of participation) is even better. Thus, we adopt a continuous conception of this key concept; countries are more or less democratic across a variety of dimensions. For ease of exposition, we sometimes refer to democracies and autocracies as if they were crisp categories, i.e., regime-types. However, our theoretical conception of democracy is non-dichotomous. The breadth of this concept introduces some degree of ambiguity into the causal theory, for it is not clear what the “treatment” might consist of. The saving grace is that most of the recognized components of democracy co-vary, so that even a loose conceptualization of the concept does not introduce a huge degree of error into the empirical analysis. Second, the five causal mechanisms identified by the theory are highly abstract. As a consequence, they are rather difficult to measure and hence to test. They also have a tendency to overlap with one another. It is difficult to say, for example, where “learning” begins and “institutionalization” ends. Even so, they represent conceptually distinct causal mechanisms that, we suppose, have strong effects on a wide range of governance outcomes. Although one might prefer a more concise theoretical framework, this should not tempt us to abandon accuracy and comprehensiveness. Insofar as democracy affects development, it seems quite likely that all five of the causal pathways sketched in this chapter are at work. Thus, we retain them in our general argument. Subsequent chapters will provide a more nuanced picture of these causal relationships as they pertain to specific policy areas (chapters 3-10) or specific country cases (chapters 11-13). Evidently, the causal mechanisms connecting regime history with economic policymaking may be somewhat different from those that extend from regime history to social policy. Even so, we believe that there is an essential consistency to the overall argument about democracy and development. Insofar as learning affects economic policy, it should also affect social policy and environmental policy. To this extent, the causal theory presented in this book is coherent and consistent, applying across a broad range of policy outcomes. Finally, we expect that there are multiple feedback loops in the diagram contained in Figure 1.2. For example, the development outcomes listed in the diagram are by no means independent of each other. Economic policies affect growth, and growth presumably affects everything else, to name only one example. A second type of feedback loop concerns the effect that developmental outcomes might have on a country’s regime-type. A country’s economic success, for example, may affect its ability to achieve, or maintain, a democracy (a matter that is disputed among scholars). These feedback loops lie outside the purview of the theory (though, naturally, they pose problems for the empirical analysis). After so many caveats and qualifications, the reader may be perplexed. Evidently, democracy’s putative relationship to development is not easy to articulate. However, it is important to keep in mind that the principal argument of the book is about the causal relationship between regime history and development. As such, the question of causal mechanisms is secondary. We are of course concerned to present a plausible account of how the accumulation of democratic experience might influence a variety of developmental outcomes. This is critical to the argument. But we are not concerned to specify precisely how this happens. This sets the bar much too high for an analysis of structural causes and distal outcomes in the social sciences, where causal pathways are often multiple, overlapping, and resistant to measurement. 17 Consider, for example, the causal effects of economic development (as measured by per capita GDP or urbanization) on human development, social policy, or state capacity. These three causal relationships are well established. Indeed, there is a virtual unanimity among scholars that economic development fosters these outcomes (though it is certainly not the only factor that matters). At the same time, there is great disagreement over which causal mechanisms might be at work, and which might be most significant. The point is, uncertainty about mechanisms, and the fact that we are well short of a unified “theory” explaining any of these outcomes, has not led anyone to doubt the existence of causality. Our theory, which also relates a structural cause to a set of distal outcomes, suffers from the same ambiguity. Again, the reasonable and achievable goal for a theory of this nature is plausibility, not precision, in the specification of causal mechanisms.51 OUTLINE OF THE BOOK [To write] To this, the chary reader might respond that the solution to ambiguities introduced by vague macro-theories is the avoidance of macro-theorizing. Yet, the cost of sacrificing macro for micro, if adopted as a general strategy in the social sciences, would be to eliminate discussion of virtually all structural causal arguments. The exception would be instances where macro theories could be successfully broken down into their constituent parts, which could be individually theorized and tested. We have already seen that this is virtually impossible to accomplish with the concept of regime type, and we suspect it is similarly challenging for other important causal factors such as economic development. Thus, our position is that the current enthusiasm for micro-level research, while warranted, should not become a new dogma. There are still many circumstances in which the messy reality of macro-level variables is all we have to work with. For further discussion of these points see Gerring (2007c). 51 18