SAMPLE Research Paper

Centanni 1

Student Writer

Professor Centanni

English 101

30 July 2015

Popular Speech for the Populace: The Simplification of Political Discourse

It certainly seems that American politics is stuck in a linguistic trend of valuing simple – often “folksy” – discourse over cerebral, challenging dialogue on issues. At some point, it became a political advantage to seem like “just another person” instead of a wordsmith. Echoing this notion, Vocativ, an online news website, performed an unofficial study in 2014 that indicates presidential speeches have become less sophisticated, on average, over time according to the

Flesch-Kincaid readability test. Their data shows that from the inception of our nation into the early 20 th century, the majority of political speeches delivered by presidents measured at a college reading level or higher. Since the middle of the century, however, speeches have hovered around the 8 th

grade level (Fox et al ). Somewhere along the line, the American populace became convinced that “truth” could only be delivered via “straight talk” in favor of intellectually complex discourse. This revelation has drastically altered the habits of political speakers.

However, is this downgraded level of communication something that is truly effective for politicians? Perhaps more importantly, does it help democracy to function in our country? These are questions that my research seeks to answer.

This paper will examine the rhetoric of two American politicians: Donald Trump and former President George W. Bush. It will examine particular strategies that each politician uses in order to appeal to their voter base. In the case of Mr. Trump, a presidential candidate, the focus will be on his strategy of “expressing outrage.” I will then analyze President Bush’s

Centanni 2 rhetorical moves of infusing his speeches with a simplified bravado. First, I endeavor to examine why each speaker opted to employ the strategies they did. Then I will look to research to see why such tactics were likely to persuade the audiences to which they were delivered. Finally, I will consider whether or not this “dumbed down” discourse helps or hurts our nation’s attempts at running a thriving democracy.

Donald Trump’s rhetorical decision to express outrage in his appearances stems from a desire to stand apart from other candidates as an “anti-politician.” He (rightly) thinks that

“politician” is a sort of four-letter-word in the minds of his audience, so he seeks to echo their frustrations in order to win them over. To the listeners whose frustrations with politicians are well-founded, Trump’s “truths” match their emotional states. This outrage can be found in his

June 2015 speech announcing his candidacy. When referring to Jeb Bush’s support for an education policy he finds ineffective, he says of his opponent, “How the hell can you vote for this guy?” (Trump). His statement is both disparaging toward a fellow candidate and informal.

Ultimately, his “truth” is that the Common Core is bad and one should not vote for a supporter of it. Unlike the typical politician, who values diplomacy and hedged language, Trump uses a mild curse word. It seems to show that, much like his constituents, he has had enough. Without the expletive, the line becomes far less of a relatable sentiment, and perhaps veers closer to a complaint. The fact that his audience breaks into applause nearly immediately after this moment seems to indicate that he struck an emotional chord with his audience and was, thus, highly effective in that particular moment. Put simply, the audience felt convinced that what Trump said was true because they, too, were mad.

Similarly, George W. Bush was well-known for building a kinship with his “fellow

Americans” by often eschewing proper English in favor of a vocabulary of bravado. This over

Centanni 3 confidence, which attracted many patriotic voters, led many media outlets in 2004 to praise Bush as “the president you can have a beer with.” However, this also led some of his political discourse to stray from policy and focus on image. After the tragic events of September 11,

2001, many in the nation were grappling with strong emotions. President Bush gave a radio address with the following message: “[T]he United States is presenting a clear choice to every nation: Stand with the civilized world, or stand with the terrorists” (Bush). At a time when citizens felt overwhelmingly passionate about restoring our nation’s pride, Bush gave an ultimatum that made it seem like he shared our passions. He convinced a vulnerable country that standing up and unifying against an abstractly defined “terrorists” would be the strong tack. The

“truth” Bush creates does not need a concrete enemy, because it has a concrete ally: us. He uses terms such as “clear” and “stand with” to simplify the issue in a way that apolitical listeners would understand. The issue was suddenly reduced to the simplicity of a backyard game of dodgeball: there is a clear line, and you must stand on one side or the other. This message does not take into account the nuances involved in identifying who exactly “the terrorists” are, nor does it seek to find answers through patient wisdom. It panders to the emotions of Americans who did not quite know what they wanted to do – but they knew they wanted to appear powerful.

Considering the context of the time period, and the sizable bump in approval George Bush earned in the months following the attacks, it is difficult to argue that this rhetorical decision proved to be convincing.

Clearly Trump and Bush found effective rhetorical means with which to convince their particular audiences to side with them; however, why would they select such strategies in favor of others? Why would Trump not rationally discuss the details of the education policy about which he criticized Jeb Bush? Similarly, why would President Bush not detail the specifics about

Centanni 4 which groups he considered to be “terrorists”? Researcher Charles Kneupper may suggest that these choices were made because political rhetoric that goes into too much detail is simply uninteresting to listeners. His 1986 scholarly article “Political Rhetoric and Public Consequence:

A Crisis for Democracy?” takes on the similar task of assessing the devolution of political rhetoric and predicting its collateral damage. His study concludes that the state of political discourse in 1986 already “constitute[d] a threat to democracy” (Kneupper 131). But why did this regression take place to begin with?

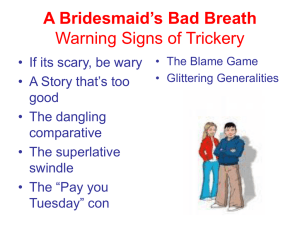

Kneupper argues this altered political climate came about largely due to the fact that the public was no longer interested in the discourse. He states, “[The public] are generally disappointed due to the vague and ambiguous language” (Kneupper 128). While the statement seems to interchange “vague” and “ambiguous,” the two words have starkly different connotations. Vague implies that something is missing while ambiguous indicates that exploration is needed. Therefore, politicians had to combat a public that felt something was either missing in the political speeches or, perhaps more dangerously, thought candidates were asking them to engage in unwanted critical investigation. Obviously, a statement that not-sovaguely asks voters, “Why the hell [emphasis mine] would you vote for this guy?” is going to leave nothing to the imagination. There is nothing unclear about what Trump is asking his listeners – no media intermediary is needed to translate. Bush’s ultimatum has the same effect, asking for minimal public engagement but still rewarding the listener with a feeling of inclusion.

They can say to themselves, “I am against terrorists” and feel as though they understand a complex situation. In other words, helping people feel involved sparks interest, which combats complacency. This is why simplistic political discourse has become so mainstream.

Centanni 5

So what does this mean for the American form of democracy? Is it going to strengthen public involvement, endanger policymaking decisions, or something else altogether? Most people agree that a democracy is a government in which the People actively participate in decisions based on obtaining as much truth as possible. The issue seems to complicate itself when such “truth” is shaped by political rhetoric. While Kneupper indeed feels that the regression in the intellectual quality of political discourse will have a negative effect on the

American political landscape, he admits that, “It is not entirely clear that the degree of the problem is accelerating. Nor is it clear that the condition was ever vastly better in the past” (131).

However, it is hard to deny that the psychological effect of “group think” may come into play more drastically if politicians continue to resort to a “rallying” approach. If issues fail to be at the forefront of political communication, voters will effectively be asked to join “teams” rather than to critically evaluate the needs of our nation and the competencies of our leaders. At that point, competing truths will be based on sponsorships and memberships rather than facts and reality.

Pandering to an audience is not something that politicians invented. In every field from the arts to business to science, leaders attempt to persuade their intended audience through identifying with them. Modern politicians Donald Trump and George W. Bush simply take this reality into the political realm through the use of colloquial speech, expressing outrage, exhibiting bravado, and simplified speech patterns. That their tactics are successful is clear; however, at what cost do these political victories come? Only time will tell. The fact of

American politics, at this point, is that Truth with a “capital T” is simply less engaging than relative truths that attract audiences and demographics. In that regard, politicians are doing whatever they need to do in order to have their “truth” heard.

Centanni 6

Works Cited

Bush, George W. “President Bush’s Weekly Radio Address.” October 6, 2001. Transcript.

Accessed July 22, 2015. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpsrv/nation/specials/attacked/transcripts/bushaddress_100601.html>

Fox, EJ, Mike Spies, and Matan Gilat. “Who Was America’s Most Well-Spoken President?”

Vocativ . October 10, 2014. Online. < http://www.vocativ.com/interactive/usa/uspolitics/presidential-readability/>

Kneupper, Charles W. “Political Rhetoric and Public Competence: A Crisis for Democracy?”

Rhetoric Society Quarterly . Vol.16, No. 3. Summer, 1986: 125-133. JSTOR Database

Search.

Trump, Donald. “Our Country Needs a Truly Great Leader.” June 16, 2016. Transcript.

Accessed July 22, 2015. <http://blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2015/06/16/donald-trumptranscript-our-country-needs-a-truly-great-leader/>