The life of Blaise Pascal

advertisement

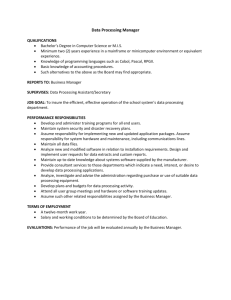

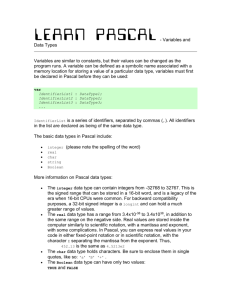

The life of Blaise Pascal BY: JEREL PATTERSON TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Life History 2. Mathematical Discoveries 3. Contributions to Society, Technology, of Field of Mathematics 4. Bibliography Blaise Pascal Blaise Pascal was born at Clermont on June 19, 1623, and died at Paris on August. 19, 1662. His father was a local judge and tax collector at Clermont. They moved to Paris in 1631, partly to prosecute his father’s own scientific studies, partly to carry on the education of his only son, who had already displayed exceptional ability. One day, being then twelve years old, he asked in what geometry consisted. His tutor replied that it was the science of constructing exact figures and of determining the proportions between their different parts. Blaise Pascal gave up his play-time to this new study, and in a few weeks had discovered for himself many properties of figures, and in particular the proposition that the sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to two right angles. At the age of sixteen Blaise Pascal wrote an essay on conic sections; and in 1641, at the age of eighteen, he constructed the first arithmetical machine, an instrument which, eight years later, he further improved. In 1642, while he was still a teenager, he started working on calculating machines, and after three years of effort and 50 prototypes he invented the mechanical calculator. He built twenty of these machines (called the Pascaline) in the following ten years. Pascal was a mathematician of the first order. He helped create two major new areas of research. He wrote a significant treatise on the subject of projective geometry at the age of sixteen, and later corresponded with Pierre de Fermat on probability theory, strongly influencing the development of modern economics and social science. Pascal showed an amazing aptitude for mathematics and science. At the age of eleven, he composed a short treatise on the sounds of vibrating bodies, and his father responded by forbidding his son to further pursue mathematics until the age of fifteen so as not to harm his study of Latin and Greek. One day, his father found him (now twelve) writing an independent proof that the sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to two right angles with a piece of coal on a wall. Following Desargues' thinking, the sixteen-year-old Pascal produced, as a means of proof, a short treatise on what was called the "Mystic Hexagram", Essai pour les coniques ("Essay on Conics") and sent it—his first serious work of mathematics—to Père Mersenne in Paris; it is known still today as Pascal's theorem. It states that if a hexagon is inscribed in a circle (or conic) then the three intersection points of opposite sides lie on a line (called the Pascal line). Pascal continued to influence mathematics throughout his life. His Traité du triangle arithmétique ("Treatise on the Arithmetical Triangle") of 1653 described a convenient tabular presentation for binomial coefficients, now called Pascal's triangle. In conclusion, if I could interview Blaise Pascal why was math more interested to him then being physicist? Pascal learned mathematic by teaching himself, he was interested in learning through his tutor. An event in my life of how I can relate to Pascal is playing basketball. Source: About.com. written by Mary Bellis, Web. 16 Oct. 2010 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, second edition, by Katz, Victory. Reading, Mass.: Addison Wesley Educational Publishers, 1998. 2. Blaise Pascal, by Bibliothèque Nationale. Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale, 1962. 3. Letters on Probability, by Renyi, Alfred, translated by Vekerdi, Laszlo. Detroit, Mich.: Wayne State University Press, 1972. (These are some of the letters Pascal wrote to Fermat.) 4. Pascal, by Krailsheimer, Alban. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 1980. 5. L'oeuvre Scientifique de Pascal, by Costabel et al. Paris: Presses Universitaire de Frace, 1964. (This is where I found the copy of Essai pour les coniques.) 6. Pascal Oevres Complètes, by Chevalier, Jacques. Paris: Gallimard, 1954. 7. Blaise Pascal: The Genius of his Thought, by Hazelton, Roger. Philadelphia, Penn.: Westminster Press, 1974. 8. An Introduction to Projective Geometry, by O'Hara and Ward. London, UK: Oxford University Press, 1937. 9. Pascal, the Man and his two Loves, by Cole, John. New York, NY: New York University Press, 1995. 10. Dictionary or Scientific Biography. 11. Pascal's Mystic Hexagram: Its History and Graphical Representation, a thesis, by Linton, Anne and Linton, Elizabeth. Philadelphia, Penn.: University of Pennsylvania, 1927. 12. Blaise Pascal, by Davidson, Hugh. Boston, Mass.: Trayne Publishers, 1983. 13. Pascal: Life of a Genius, by Bishop, Murray. New York, NY: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1936.