A Bank of England Conspiracy - Political Research Associates

advertisement

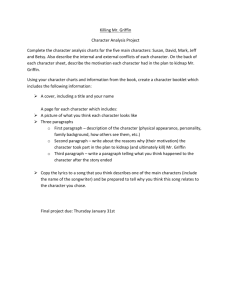

A Bank of England Conspiracy? ©1997 by Gerry Rough The Bank of England holds a special place in the hearts of New World Order conspiracy theorists. It is here that the central banking mechanism begins to appear in the pages of history, although in the late seventeenth century it was still not a central bank in the modern sense. Considered by many to be the virtual hub of the New World Order, the Bank has somehow managed to remain a mystery to be solved; no small temptation indeed for the faithful. With this new mechanism in place, the New World Order can now begin its final assault to enslave the planet. The central banking mechanism, you see, represents the power of the rich to control the masses. It represents one of the last steps to be put in place before the New World Order finally reveals itself as the dark beast that it is. Lets take a look at the history of the Bank of England and see if indeed there is a conspiracy that emerges. G. Edward Griffin provides our first glimpse: England was financially exhausted after half a century of war.Unable to increase taxes and unable to borrow, Parliament became desperate for some other way to obtain money.There were two groups of men who saw a unique opportunity arise out of this necessity. The first group consisted of the political scientists within the government. The second was comprised of the monetary scientists from the emerging business of banking.The two groups came together and formed an alliance. No, that is too soft a word. The American heritage dictionary defines a cabal as "A conspiratorial group of plotters or intriguers." There is no other word that could so accurately describe this group.The Cabal met in Mercer's chapel in London and hammered out a seven point plan which would serve their mutual purposes.[1] Conspicuously absent from Griffin's text, however, as well as all other conspiracy texts, Parliament actually had several schemes for producing new revenue. More importantly, Sir John Clapham, author of the classic The Bank of England: A History, puts these new banking schemes into a much broader context: In June 1687 there began to reach London the first treasure salved by an English company from a Spanish ship lost over forty years earlier near Hispaniola.This whetted the appetite of the promoters the projectors as they were called of a vigorous and inventive age, in which all sorts of men were "joining their heads to understand the useful things in life", and to make money. The Revolution over and Dutch William on the throne, a whole series of treasure hunting companies was set up, forerunners or products of the promoting boom of 1692-5, in which both the Bank of England and the Bank of Scotland came into existence [2] So Griffin's assertion of conspiracy falls under its own weight when viewed as a larger movement during the 1692-1695 time period. Further, Parliament rejected William Paterson's idea not once, but twice before finally passing the law: a blatant contradiction not found in any writings of conspiratorial repute. [3] Of interesting note, the Bank of Scotland mentioned above was formed under almost identical circumstances yet is nowhere mentioned as part of the New World Order. It would seem as though history itself has provided its own argument against the conspiracy theorists. The "treasure hunting companies" mentioned above should not be interpreted in the modern context of those seeking lost treasure. Rather, Clapham is speaking of those finding new and inventive ways of making money, most of which ended in failure. [4] The meeting at Mercer's chapel? Hardly a conspiracy, it was completely public. Anyone who wanted to subscribe to the original stock could do so. As R.D. Richards puts it: [A]ny person or persons, natives or foreigners, bodies politic or corporate. [5] Let's not forget the seven point plan, either. It never existed. Griffin himself fabricated the idea from the two sources he gives for it. [6] Griffin again provides more analysis: The new money created by the Bank of England splashed through the economy like rain in April.Consequently, when these plentiful banknotes landed in their [the country banks] hands, they quickly put them into the vaults and then issued their own certificates in even greater amounts. As a result of this pyramiding effect, prices rose 100% in just two years. Then, the inevitable happened: There was a run on the bank, and the Bank of England could not produce the coin.In May of 1696, just two years after the Bank was formed, a law was passed authorizing it to "suspend payment in specie" [suspend payment in gold for the face value of the note being presented]. By force of law, the Bank was now exempted from having to honor its contract to return the gold. [7] It's the old delete and switch routine. What Griffin deleted was the facts behind the bank of England's suspension of specie payment. R. D. Richards fills in the blanks: Indeed, the Bank was so heavily involved in the "business of remises," as it is usually termed in the court minutes, that the directors reported to the treasury in 1696 that they had "extreamely strained themselves." [8] But Richards analysis does not stop there. Chapters VI and VII of his text are an indepth study of "The Early Transactions of the Bank of England." Richards continues his analysis: Thus within ten weeks of its foundation, and before it had paid to the Government the final installments of its original loan of £1,200,000, the bank had commenced to remit large sums overseas.When it is recalled that at the time the last of these grants of credit was made the Bank had not completed its first seven months, and that it had advanced to the Government before 6th February 1695 not only the whole of its original capital of £1,200,000, but also a further sum of £300,000, these early remittances overseas were remarkable transactions. But there were even bigger remittances to follow within the next eighteen months.Meanwhile, however, as already stated, large sums were also remitted by the Bank to Savoy, and for the use of the fleet. [9] So the suspension of specie payment had nothing to do with the pyramiding effect mentioned in Griffin's text. It had EVERYTHING to do with the fact that the Bank was overextended by force of both Parliament and the crown. Richards continues: [T]he court had resolved to discontinue the remittances to Holland, after having come to the conclusion that the borrowing of another £200,000 in Holland would not "keep them in the business.".Despite this decision the King ordered them to continue the remittances. [10] The absurdity of calling it a conspiracy when half of the conspiracy is forcing the other half to obey, is not a conspiracy at all. And that's just for starters. There were other factors as well. [11] But by far the most damaging to Griffin's case from the above citation is that the Bank of England was not to blame for the bank run in 1696. In fact, it was literally the ENEMIES of the Bank who conspired to make a bank run! That’s right, the ENEMIES of the Bank are the real conspirators! But first, lets digress for a moment to size up the opposition. The first of these groups were the Tory party and the Jacobites. This group feared that the bank would become too strong, and that if the Bank ever failed to meet its obligations, it would be powerless for lack of funds. Indeed the Tories believed the institution was not compatible with a monarchy. Further, it may even be one step closer to a [gasp!] REPUBLIC! The second of these groups was the country gentry and the small land owners who feared that the Bank would charge excessive interest rates on loans. The last and most important of the large opposition groups was the goldsmiths and the money-lenders, who were fearful of the new scheme that might endanger their profits. [12] It was this last group whom Andreades speaks of when he would later write: [O]n May 6, when the goldsmiths organized a run on the Bank of England, the latter had not enough coin to meet the suddenly increased demand. [13] Further damaging to Griffin's case is the words of every conspiracy theorists accidental ally, Murray N. Rothbard, the avowed enemy of central banking and professor at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, cult of libertarian think: [I]n the short span of two years, the Bank of England was insolvent after a bank run, an insolvency gleefully abetted by its competitors, the private goldsmiths, who were happy to return to it the swollen Bank of England notes for redemption in specie. [14] So we find on further examination that Griffin is seriously lacking in his presentation of the facts and that the enemies of the Bank were really the ones to blame for the bank run of 1696. In yet another twist of conspiratorial fate, William Paterson would be forced to leave the Bank within a year over a major policy dispute. To his credit, Griffin acknowledges this, [15] but fails to see the obvious contradiction. Bob Adelmann never knew of Paterson's removal, and hence blindly writes of the bank run of 1696: This incident underscores the power and influence that Paterson and others had over the financial affairs of the English government. [16] A conspiracy of this magnitude would never think of forcing one of their own fly the coup. Paterson would have no doubt donned cement shoes if there was truly a conspiracy at work. This argument alone is seriously damaging to the conspiracy theorists case. As mentioned earlier, there were several competing schemes at the time the Bank of England was formed. But even after the bank was formed and had already begun its initial operations, Parliament would pass yet another banking scheme, that of the Land Bank. The venture would quickly turn sour, however, and Parliament would be forced to call on the Bank of England to help clean up the mess. [17] As the early history of the Bank of England unfolded, there appeared yet one more major attempt to circumvent the Bank to pay the National debt. This second attempt was the famous South Sea Bubble of 1720. It too would meet a premature death, while the bank of England would again be asked to clean up the mess left by its own competitors. [18] The point of all of this is to point out that the same Parliament that "conspired" to create the Bank of England, also created its fiercest rivals, both within the first twenty-five years of its existence. One less enamored with conspiracy theories would be tempted to ask some obvious questions at this juncture. One of the presuppositions of the central banking issue that you read most often in conspiracy writings is that the Bank of England was a central bank from the very beginning. This fits the New World Order theory very nicely, since it conveys the idea that the conspirators had enormous power even as far back as 300 years ago, and have been gaining power and global influence ever since. Before putting this theory to the test, let's see what the opposition says on the subject. Pat Robertson states matter-of-factly in his text, The New World Order: But what is a central bank? The idea first occurred to a canny Scot named William Paterson, who in 1694 agreed to establish a joint stock company to loan £1.2 million at 8 percent interest to William of Orange to help the king pay the cost of his war with Louis XIV of France. [19] J.R. Church makes a similar error in his book, Guardians of the Grail, although in this citation, it is more assumed than it is stated: For example, in 1694 international banker William Paterson obtained the charter of the Bank of England, and the power over England's money system fell into private hands.Two hundred thirty years later, Reginald McKenna, British Chancellor of the Exchequer said, "The banks can and do create money and they who control the credit of the nation direct the policy of governments and hold in the hollow of their hands the destiny of the people." [20] But there is another side to the story. Historian H.V. Bowen exposes the error succinctly when he states: The Bank of England during the eighteenth century was not a central bank in the modern sense. By the end of that century the Bank had acquired some of the features of a central bank as now understood, but the Bank had neither been established, nor consciously developed, with central banking functions in mind. Instead, the Bank followed two separate, though overlapping, lines of development which, in their different ways, drew it close to the realm of modern banking. Such was the hesitant nature of both developments that the characteristics of central banking only emerged slowly as the Bank began to gain the capacity to act as lender of last resort and regulator of financial activity within the economy at large. It was only when these separate lines of development began to meet at a point in the early nineteenth century that the Bank began more clearly to display the characteristics of a central bank. [21] G. Edward Griffin acknowledges the error of other conspiracy theorists by stating: It must be understood that, at this time [early in its history], the Bank of England was not yet fully developed as a central bank. [22] Be ye not quick to sigh, however. Griffin contradicts himself on numerous occasions on this very issue, the following being but one example: The charter was issued in 1694, and a strange creature took its initial breath of life. It was the world's first central bank. [23] So again we find the conspiracy theorists sorely lacking even on the most basic of issues regarding the history of the Bank of England. But, unfortunately, our journey must take two more twists. First, recall that J.R. Church stated above that "they who control the credit of the nation direct the policy of governments." Assuming this to be true, that central banks have absolute control over their respective governments, it is difficult to imagine how the Bank of England could have gone from private hands to public hands in 1946, which it did when Parliament revoked the charter and nationalized the Bank. Church even tries at this point to explain the obvious contradiction: In 1946 England's labor government revoked the charter and nationalized the Bank of England. Officially, it became a part of the government. It is important to note, however, that as late as 1961 Lord Cromer, of the banking family of Baring, was named governor of the bank, and the board of directors included representatives of Lazard, Hambros, and Grenfell-- the same banking families who had previously controlled the board! Nothing had changed except for outward appearances for the benefit of the uninformed. [24] Consistent with conspiratorial absurdities, "Lord Cromer," of the above citation, is really George Rowland Stanley Baring, The Earl of Cromer. [25] Worse yet, Church never bothered to take a head count before stating his argument. Let's see now: Duck, duck, duck, duck, duck, goose, duck, duck, duck, duck, goose, duck, duck, goose, duck, goose. I count twelve ducks and four goose. You have to wonder if he ran out of toes or something. [26] Our last conspiratorial absurdity is that committed by Bob Adelmann mentioned earlier. Adelmann states: The First Bank of England In 1694, William Paterson created the First Bank of England. [29] Imagine, if you will, submitting a serious research paper entitled "George Washington, The Third President of the United States." Or a Doctoral dissertation on the history of President John Forsythe Kennedy. Or maybe the Japanese attack on Washington, D.C. harbor, December 7th, 1941. In every measurable sense, this is the same magnitude of error that Adelmann has done. By calling the Bank of England the "First" Bank of England, he has both destroyed his own credibility, while at the same time he has exposed the weak link of the conspiracy camp. Conspiracy theorists thrive on the ignorance of their audience. This should not be taken to mean or imply that conspiracy theorists are less intelligent than everyone else. This is certainly not the case. But it's a great reminder though, that ignorance does indeed breed suspicion. Sources 1) G. Edward Griffin, The Creature from Jekyll Island (Appleton: American Opinion Publishing, Inc., 1995) 175, 176 2) Sir John Clapham, The Bank of England: A History (New York: The Macmillan company, 1945) 13, 14 3) A. Andreades, History of the Bank of England: 1640-1903 (New York: August M. Kelley, Bookseller, 1966) 65-67 4) Sir John Clapham, p. 14 5) R. D. Richards, The Early History of Banking in England (London: Frank Cass and Company,Ltd., 1958) 146 6) Martin Mayer, The Bankers (New York: Weybright & Talley, 1974) 24, 25. See also Rothbard, p. 180 7) Griffin, p. 178, 179 8) Richards, p. 179 9) Richards, p. 183, 184 10) Richards, p. 188 11) Richards, p. 189 12) Andreades, p. 67-69 13) Andreades, p. 107, 108. See also Richards, p. 189 14) Murray N. Rothbard, The Mystery of Banking (New York: Richardson & Snyder, 1983) 181 15) Griffin, p. 176. 16) Bulletin: Committee To Restore The Constitution, February, 1989. P.O. Box 986, Ft. Collins, CO 80522 17) Andreades, p. 103-113 18) Andreades, p. 128-145 19) Pat Robertson, The New World Order (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1991) 120 20) J.R. Church, Guardians of the Grail...and the men who plan to rule the world! (Oklahoma City: Prophecy Publications, 1989) 193 21) Richard Roberts and David Kynaston, ed., The Bank of England: Money, Power and Influence 1694-1994 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995) 1,2 22) Griffin, p. 174 23) Griffin, p. 176 24) Church, p. 193-194 25) Roberts and Kynaston, p. 274 26) Roberts and Kynaston, p. 197 27) Bulletin: Committee To Restore The Constitution, February, 1989. P.O. Box 986, Ft. Collins, CO 80522 Additional Resources Norman Angel, The Story of Money (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1929) Elgin Groseclose, Money and Man (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976) W. A. Shaw, The Theory and Principles of Central Banking (London: Sir Isaac Pitman sons, Ltd.)