Unit 8 Coursepack - Community Charter School of Cambridge

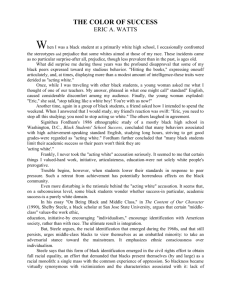

advertisement