Ph.D DOCUMENT.doc

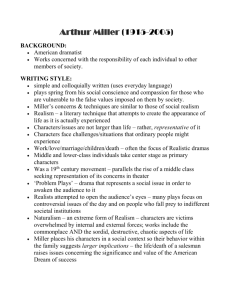

advertisement