Journey`s End - Annan Academy English Department Blog

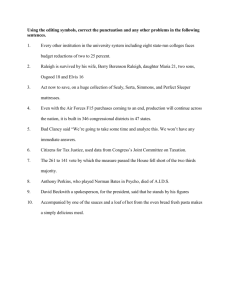

advertisement

Journey’s End by R.C. Sherriff (Page numbers from the Penguin Modern Classics 2000 edition) Introduction Act I Act II Act III Introduction R.C. Sherriff was born on June 6 1896 in Surrey. In 1915 he joined the East Surrey Regiment and in 1917 he was wounded at Passchendaele. He spent six months in hospital then returned to his job in the Sun Insurance Office in London. Journey’s End was first performed in late 1928 early 1929 with Laurence Olivier playing the part of Stanhope. It was Sherriff’s seventh play but the first to be successful. Sherriff died on 13 November 1975. When he tried to get a commission in the army as an officer he was told that only young men leaving public school were given commissions. However, the army had to rethink this rule after so many men were killed. In 1915 Sherriff became a captain in the East Surrey Regiment. The play is based on his experiences in the war. When war broke out in 1914 everyone thought it would be short-lived and many young men saw joining the British Army as an ‘adventure’. They had no idea what the fighting would be really like. Set in St Quentin, France in 1918, the play begins on Monday 18th March, three days before Germany launched ‘Operation Michael, an attack on St Quentin. The attack was part of the Spring Offensive, an attempt by the Germans to break through and separate the British and French forces. War came to an end on 11th November 1918. In the 1920s the class system was changing and many people who had never been to the theatre before started going. Few plays at the time were political or commented on social events. Few war plays were a success. However, Journey’s End, written in traditional form, proved to be a turning point between old and new theatre. Historically accurate, the setting is very important as it has come to be viewed as a play about the truth of war. Sherriff did not intend the play to explore the rights and wrongs of war. He wrote in his autobiography that his characters were ‘simple, unquestioning men who fought the war because it seemed the only right and proper thing to do … (it was a play) in which not a word was spoken against the war … and no word of condemnation was uttered …’ What he hoped to do was to show ‘how men really lived in the trenches, how they talked and how they behaved.’ All of the action takes place in the dugout where the British soldiers eat and sleep. Sound and lighting are used throughout to create a realistic and theatrically effective image of war. The basic living conditions – the drying of the sock etc – remind us of the hardships the soldiers endured. They spent a lot of time waiting and doing nothing in cramped conditions. Even in such conditions duty, loyalty and bravery emerge demonstrating the nobility of the soldiers and reminding us of the horrible wreckage of their young lives and the futility of their deaths. Act 1 Act 1 (Part 1 pages 9-15) Osborne, Stanhope’s second-in-command, takes over from Hardy, an officer of another regiment. The opening sets the scene, providing us with information about the conditions of war and its effect on the men. We also gain insights into the characters especially Stanhope who is discussed at some length by Hardy and Osborne before he appears on stage himself. The stage directions describe the starkness of the setting. Light is provided by candles, disinfectant is added to the drinking water to kill microbes; the drying of Hardy’s sock over the candle flame indicates the damp/wet conditions; and rats and earwigs are mentioned later. Hardy is cheerful – he is singing and humming – flippant, clearly untidy and disorganised. He seems to rely on the sergeant major to check on details. Osborne is ‘fussy’ and keen to get everything prepared correctly for Stanhope. Hardy, on the other hand, is keen to leave before Stanhope arrives to find fault. The song he sings might seem unimportant but it mentions women in a place where there are none and time which is a recurring motif in the play. Life in the trenches is a waiting game – “Sometimes nothing happens for hours on end; then – all of a sudden – ‘over she comes! – rifle grenades…’ ” (p10). Hardy provides information about the expected German attack and details of guns and ‘posts’. We also learn that a new officer is expected. Hardy describes Stanhope as a ‘freak’, a hardened drinker and implies that Osborne would be a better commander. From Osborne we learn that Stanhope has been involved in the war for almost three years. ‘He came straight from school – when he was eighteen. He commanded this company for a year – in and out of the front line. He’s never had a rest…’ (p13) ‘He’s a long way the best company commander we’ve got.’ (p12) ‘I’ve seen him on his back all day with trench fever – then on duty all night’ (p13) ‘There isn’t a man to touch him as a commander of men. He’ll command the battalion one day if – ’ (p14) As the play progresses we gain greater insight into Stanhope through what others say and do and through what we see of him himself. (Part 2 pages 15-22) Osborne and Raleigh talk. Osborne appears approachable. He engages in light-hearted conversation with both Mason and Raleigh. Mason is able to confide in him about the pineapple chunks/apricot mixup and hopes he will intercede on his behalf with Stanhope. The others call Osborne ‘uncle’ suggesting that his advice is sought by the younger soldiers. Raleigh is surprised by the quiet and the waiting for something to happen. ‘I never thought it was like that’ highlights not only his inexperience but also the false expectations that many had of war. Raleigh represents the romantic, idealistic beginner. His ‘boyish voice’ and the stage directions ‘self-consciously’ and ‘laughs nervously’, suggest his youth and inexperience. We learn more about Stanhope from Raleigh. That he should have organised things so as to be sent to Stanhope’s company shows that Stanhope commands loyalty. Raleigh knew him from school. The reference to Stanhope’s anger at the boys drinking whisky is ironic in view of what we have already heard about his own drinking but helps us to understand Stanhope’s reluctance to go home and be seen as he is now – he is so far from his own idea of what a ‘fit’ young man should be like. Osborne tells Raleigh – and us – that Raleigh ‘mustn’t expect to find him – quite the same.’ War has been ‘a big strain’ on him. The language and topic of conversation – rugby and cricket – remind us of their public school background whilst the talk of food adds comic relief. Any diversion – including earwig racing – is essential to their survival. (Minnies are German guns, mine-throwers.) (Part 3 pages 22 – 28) The arrival of Stanhope The stage directions establish Stanhope as young and good-looking with a smart uniform but the ‘pallor under his skin and dark shadows under his eyes’ indicate the strain he is under. He is caught off guard by Raleigh’s presence and tells Mason off. Trotter is different from the others in that he has a working-class accent and has clearly not been to public school. His carefree and jovial attitude helps to lighten the atmosphere. He clearly likes food – we may come to suspect that he uses it in the same way as Stanhope uses drink. The comic play over the boxes used for seats and his talk about food lighten the mood. His drawing of the circles (one for each hour) and remark about the revolvers being needed to shoot the rats show he has found ways to cope with stress. The rats and the need for pepper as a disinfectant remind us of conditions in the trenches. The men also have to put up with not knowing what will happen next. (Part 4 pages 28-35) Hibbert represents the conflict between cowardice and heroism. We see the psychological effects of war on a man. Stanhope is unsympathetic. He thinks Hibbert is using ‘neuralgia’ as an excuse and refers to him as a ‘worm’. Osborne can see that Stanhope is utterly exhausted. The colonel, he says, recognises that leave is ‘due’ to Stanhope but they cannot afford to lose him. Stanhope confesses, ‘without being doped with whisky – I’d go mad with fright.’ It was the horrors he saw at Vimy Ridge that caused him to take to drink. He is worried that Raleigh will reveal the truth to his sister. Stanhope feels responsible for Raleigh but wants to prevent the truth from reaching Madge. Osborne tucks Stanhope into bed – once more taking on the role of carer. Their closeness makes Stanhope’s later loss all the greater. Symbolically at the end of Act I, Osborne winds up his watch as if suggesting that the move towards an end is only a matter of time. It is clear here that Stanhope is in a distressed state when he describes Raleigh as ‘a little prig’. His decision to censor Raleigh’s letters is a sign of the despair and paranoia he feels as well as an example of the abuse of power we see him demonstrate on a number of occasions in the play. Act II Part I (pages 36-40) Once again the conversation about food provides light relief after the tension of the end of Act I and Stanhope’s decision to censor Raleigh’s letter. That the sound of a bird is funny is significant. The men at war feel separated from the real world – the natural world. This idea is reinforced when Trotter recalls the incident when the scent of the may-tree was confused with a gas attack. The numerous references to how quiet it is are a reminder that an attack is imminent and suggest the coming tragedy. The talk of duties and war and jam make us acutely aware of how war has become the normal state of affairs for these men. Whilst the men recognise and respect Stanhope for his service to his country, they are also acutely aware of the effects on him. They can see that he is ‘ill’ and his behaviour is erratic. Trotter says: ‘Nobody’d be well who went on like he does.’ Stanhope tells Raleigh to go to bed ‘just as if Raleigh’d been a school kid’ – a reminder to us of how they knew each other before the war and evidence that Stanhope wants to protect him as he once did at school. The conversation about gardening allows us to see how sharing memories of home comforts the two older and married officers. Part 2 (pages 40-42) Despite having been at the front only a few hours Raleigh says, ‘I feel I’ve been here ages.’ The constant references to time and how quiet it is reinforce the grinding effect of boredom upon the men. Their conversation draws attention to the divide between the men at the front and the politicians whose war they are fighting. Osborne tells the story of the Germans allowing them to carry a wounded man back to safety – an example of the humanity, the human decency, that exists on both sides – but Sherriff (for all his claims that this is not an anti-war play) demonstrates the futility and callousness of war when Osborne ends his account of the incident by describing how, ‘Next day we blew each other’s trenches to blazes.’ We can only agree with Raleigh when he says how ‘silly’ it all seems. Raleigh is impressed when he discovers that Osborne played rugby for England but Osborne knows that ‘It doesn’t make much difference out here!’ The dramatic irony of Raleigh referring to writing a letter home just as Stanhope enters leads us to anticipate conflict. Part 3 (pages 42 -47) Stanhope’s abilities as a leader and strategist are seen here when he talks to Osborne about the company’s ‘strong position’. The imminence of the German attack is made clear. They will have no ‘help from behind’. We are once again reminded of the torturous effect of time when Osborne says, ‘Well, I’m glad it’s coming at last. I’m sick of waiting.’ Stanhope envies Trotter’s lack of imagination and recognises that he himself may be going ‘potty’. Mason’s entrance once again relieves the tension briefly before Raleigh enters and asks what he should do with his letter. Part 4 (pages 47-49) Stanhope bullies Raleigh over the letter. Raleigh forgets for a moment that his relationship with Stanhope is not what it was and addresses him as Dennis. Stanhope is quick to remind him that he is not in school anymore and he is Raleigh’s superior officer. Our sympathy is with Raleigh even though we understand why Stanhope is worried about what the letter might say. Stanhope is embarrassed at his own behaviour and cannot bring himself to read the letter. Through Stanhope, Sherriff has built us up to believe that Raleigh will have told his sister the truth about Stanhope. However, the letter is full of admiration and praise. Stanhope is ashamed of his underestimation of Raleigh and moves into the shadows on the stage. The audience can see, as Stanhope does, that Raleigh is clearly more aware of his captain’s worth than Stanhope believed. The shining sun at the end of this scene is symbolic of the light of knowledge that the letter brings for all of us. Part 5 (pages 50-54) We see Stanhope in his role of commanding officer when he talks to the sergeant major. The situation is clearly hopeless and Stanhope is acting under orders to hold position. The colonel confirms the date for the big German attack but also brings news of a British raid to take place on the German line. Both he and Stanhope think the timing is wrong but the general has given his orders. The colonel must follow the general’s orders and Stanhope, in turn, has no choice but to follow the colonel’s orders. Stanhope bravely offers to lead the raid but the colonel immediately dismisses any such suggestion. As commanding officer, Stanhope is far too important. The colonel suggests Osborne and Raleigh instead. Hibbert is not considered stable enough and Trotter is too fat to ‘make the dash in’. Stanhope comments that, ‘It’s rotten to send a fellow who’s only just arrived’ but the colonel insists he’s ‘just the type. Plenty of guts – .’ For all that R.C. Sherriff claimed his characters were ‘simple, unquestioning men’ it is easy for the modern audience to see this as a criticism of the way absent politicians and high-ranking officers sent men to their deaths. For C Company, time is quite clearly running out. Part 6 (pages 54-59) We the audience are in no doubt about Stanhope’s feelings about Hibbert and his supposed illness as he made them abundantly clear earlier in the play. When Hibbert enters he is completely unaware of this. The dramatic irony of this (bearing in mind that Stanhope is unhappy about the raid) leads us to expect conflict. Stanhope has indeed spoken to the doctor so that Hibbert will not be given leave on medical grounds. Stanhope’s lack of sympathy and his threat to shoot Hibbert may cause us to be less sympathetic towards him. However, his ability to win Hibbert round is a testament to his qualities as a leader. When his tough approach is unsuccessful, he recognises Hibbert’s desperation and confides in him in a way we have previously only seen him confide in Osborne. He makes Hibbert feel he is not alone and offers his support to ‘see if we can stick it together.’ ‘We all feel like you do sometimes, if you only knew. I hate and loathe it all.’ He plays on Hibbert’s feelings of guilt, his loyalty to the other men and his sense of duty, honour and decency. Hibbert has been psychologically damaged by war. He would prefer to know when he is going to die and be ‘ready’ for it than face the endless waiting. Part 7 (pages 59-64) The tension of the last scene is at first relieved by the discussion of food and the onion tea. When Osborne enters and talk turns to the raid, the scene once more becomes tense. Stanhope knows (‘I’m damn sorry’) that there will be casualties. However, Osborne accepts the situation and knows Stanhope will be able to recruit volunteers – evidence of the heroism of the company and the loyalty Stanhope commands. Again we are reminded of the distance between the soldiers at war and those who make decisions regarding events at the front. Osborne’s controlled and understated treatment of the subject highlights the way in which people’s lives are being treated as unimportant. Only Trotter openly states how stupid it all seems: ‘Joking apart. It’s damn ridiculous making a raid when the Boche are expecting it.’ The rhyme from Alice in Wonderland holds a truth. Like the crocodile that charms and smiles, the First World War enticed men to join up in the hope of glory, only for them to be used as cannon fodder. The act ends with Osborne writing what will be his last letter to his wife, Stanhope going on duty with a terrified Hibbert and Raleigh returning from duty with all the excitement of a new recruit hungry for glory and unaware of its cost. Act III Part 1 (pages 65-68) Stanhope’s nervousness is apparent in his pacing, his anxious look at his watch (indicating the importance of time). It is clear that he hoped for a change of plans when he talks to the colonel. His bitter comment: “They can’t have it later because of dinner, I suppose” shows just how unhappy he is with the commanding officer’s decisions. The enemy has placed red flags along the wire, suggesting the men’s deaths. The colonel obviously feels uncomfortable and whilst he says their actions could win the war he reminds them to empty their pockets so that if they are taken prisoner they have nothing that might be of use to the enemy. Part 2 (pages 68-73) Aware of the dangers of the raid, Osborne passes on his belongings to Stanhope, signalling the coming tragedy. The awkwardness increases as Raleigh and Osborne wait. They smoke and talk. The silences and pauses indicate once more the fear and tension on stage. Osborne looks at his watch, signalling the return to reality. When Raleigh notices Osborne’s ring on the table, Osborne is not entirely truthful about his reasons for leaving it behind to protect Raleigh from the knowledge of his true motives. Note the countdown – time – waiting – time running out. Part 3 (pages 73-77) When the young German soldier is questioned we see how little information is extracted and how high a price has been paid. That Stanhope leaves the colonel to carry out the questioning and goes to see the men after the raid shows his loyalty to his company. Stanhope’s words are bitter and show his sadness and sense of loss: ‘Still it’ll be awfully nice if the brigadier’s pleased’ ‘Did you expect them to be all safely back, sir?’ Raleigh’s behaviour and appearance suggest the trauma he has endured. He ‘sits with lowered head’; his hands are covered in blood. Stanhope’s voice is ‘expressionless and dead’ when he says, ‘Must you sit on Osborne’s bed?’ Part 4 (pages 77 – 83) The mood is a stark contrast to the tension of the preceding scene. Hibbert is unusually talkative, sharing his postcards of women with the others and making jokes. They are celebrating knowing that they might die in the morning. Stanhope’s call for whisky on top of the champagne is a reminder of the strain he is under. The mood changes when Stanhope learns why Raleigh is absent. Stanhope’s anger kills the celebration and he orders Hibbert to bed. He tells Trotter he envies his ability to stay calm. When Trotter says: ‘Always the same am I? (He sighs) Little you know,’ it suggests that he too hides his true feelings. When he is told he is second-in-command he says, ‘I won’t let you down.’ He, too, is anxious to do his best for Stanhope. Part 5 (pages 83 – 86) Raleigh is obviously uncertain of the reception he will receive. Stanhope’s disappointment in him is evident when he confronts him over his absence at dinner. Stanhope loses control, clearly upset at Osborne’s death. The scene ends with the personified sounds of war – ‘the impatient grumble of gunfire that never dies away’ – a reminder of the constant threat of attack that trench life brings. Stanhope rarely reveals his true feelings. However, in this scene he does. ‘My God! You bloody little swine! You think I don’t care – you think you’re the only soul that cares! … The one man I could trust – my best friend – the one man I could talk to as man to man – who understood everything – and you think I don’t care – But how can you when - ? To forget, you little fool – to forget! D’you understand? To forget! You think there’s no limit to what a man can bear? Part 6 (pages 86 – 89) Mason wakes Stanhope at 5.30. Trotter is already awake and has woken the others, a clear indication that he is taking his role as second in command seriously. His singing and Stanhope’s joke about ‘pâté de foie gras’ relieve the tension. We are reminded of Osborne and Raleigh before the raid when the men are to be given ‘a decent spot of rum’. We expect a similar loss of life and remember that they are not to expect help and are under orders to hold their position. The supply of whisky is at an end as is the play and the men’s lives. Stanhope and Raleigh exchange casual greetings before Raleigh leaves the dugout. Part 7 (pages 89 -91) By the time Hibbert is called, the attack is in full swing. ‘He is very pale … he is the picture of misery.’ He asks for water and sips it slowly as a delaying tactic. Stanhope forces Hibbert to leave by telling Mason that Hibbert will guide him to the front line. Part 8 (pages 91 to the end) When the soldier arrives with the news from the front line it is clear things are not going well. There are many casualties and shells are heard throughout. Stanhope is preparing to join the others when news of Raleigh’s injury arrives. He asks that Raleigh be brought to the dugout – evidence of the responsibility he feels towards Raleigh. Sherriff describes him being carried in ‘like a child in his huge arms’ and he is referred to as ‘the boy’ in the stage directions reminding us (as if we needed a reminder) of just how young he is. This makes the tragedy of his impending death all the more acute. Raleigh represents the thousands of young soldiers who died in the First World War. Significantly, Stanhope has made Osborne’s bed ready for Raleigh. He addresses him by his first name. The talk of rugby reminds us of their shared history. Stanhope tries to make light of Raleigh’s injury but the change in Raleigh’s voice when he finds he cannot move his legs tells us that he has realised that he is dying. As he dies ‘the faint rosy glow of dawn is deepening to an angry red’. ‘It’s so frightfully dark and cold.’ Is he referring to the dugout or to death? Stanhope is shocked. As he leaves he runs his fingers tenderly over Raleigh’s hair and after he has gone the dugout collapses into the darkness. The ‘red dawn’ symbolises their lost blood and the dull rattle of machine guns the continuing battle.