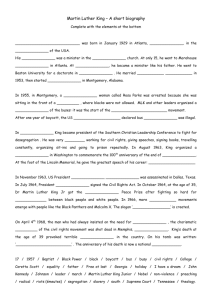

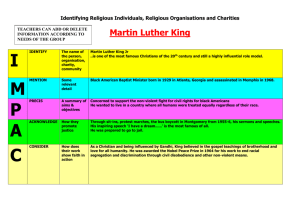

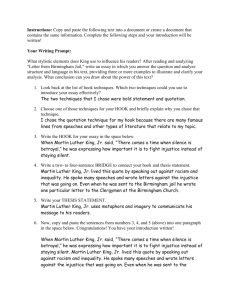

Secondary 2016 Martin Luther King Instructional Resource Guide

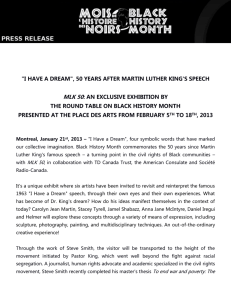

advertisement