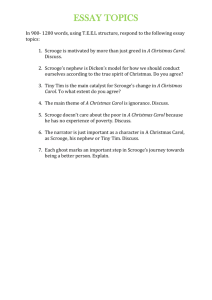

A Christmas Carol

advertisement