Paper for Conf on Org Routines

advertisement

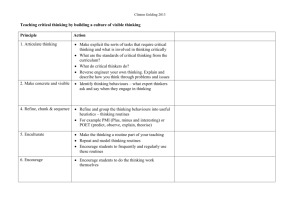

USING PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT AS AN INSTRUMENT OF CHANGE: THE MICRO ASPECTS OF ‘MANAGING THROUGH MEASURES’ Andrey Pavlov Centre for Business Performance Cranfield School of Management Cranfield MK43 0AL United Kingdom andrey.pavlov@cranfield.ac.uk Mike Bourne Centre for Business Performance Cranfield School of Management Cranfield MK43 0AL United Kingdom ABSTRACT Performance management has integrated the insights from various fields of management knowledge into a broad perspective that can offer a number of sophisticated and effective ways of managing organizational development. However, in order to realize this potential, the performance management field needs a strong theoretical foundation that can explain the mechanics of its impact on organizational processes. We argue that such foundation is provided by the organizational routines literature. We review the literature on performance management and organizational routines to propose a model which explains the effects of performance management on the evolution of routines. The model suggests that performance management uses its measurement function to affect organizational routines in three distinct ways: by triggering, leading, and stimulating the iterations between changes in the ostensive and the performative dimensions of a routine. The paper closes with a discussion of research implications stemming from the relationships proposed in the model. Keywords: Organizational routines; Performance management; Performance measurement Introduction Performance management (PM) is a relatively new term in management literature. While the issue of managing organizational performance has been a topic of interest for a long time, the field itself did not emerge until the early 1990’s. Since then PM has progressed from providing general recommendations on improving performance to formulating comprehensive PM frameworks and systems (Folan and Browne, 2005), and finally to the issues of implementing and using PM systems to manage organizational performance. As such the field has come to realize that PM systems are an integral part of the organization, which means that they accomplish their objectives by affecting multiple organizational processes that deliver organizational performance (Bourne et al., 2003; Kennerley and Neely, 2002, 2003). However, the field is lacking an organizational theory foundation that would allow it to address adequately the challenge of managing performance in its organizational complexity. 1 In this paper, we argue that this challenge is best addressed by adopting an organizational routines perspective on PM and treating organizational processes as routines. There are two major reasons for this argument. First, this perspective lends the PM field a much needed insight into the organizational structure and processes underlying performance. Second, we suggest that PM has developed a number of distinct ways of influencing organizational performance, which correspond remarkably closely to some of the key developments in the organizational routines literature. This makes PM a suitable candidate for being used as an instrument for affecting organizational routines. We assume the view that PM accomplishes its objective of managing performance in its organizational complexity by influencing the development of organizational routines. Responding to this view, we then propose a model that links together the insights from PM and the organizational routines literature in order to explain the dynamics of this effect. We argue that the evolution of organizational routines can be influenced by performance measurement – a key tool of PM – in three distinct ways: by initiating, guiding, and intensifying iterations between adjustments in the ostensive (abstract concept) and the performative (concrete action) dimensions of a routine. The paper is structured in the following way. It opens with a review of the literature on organizational routines and performance management. First, the organizational routines literature is reviewed in so far as it informs the main question of using PM to affect organizational processes. Particular attention is devoted to the distinction between understanding routines as cognitive regularities and behavioral patterns. We then review the management control systems and performance management literature in order to identify the key elements of the PM process that make it a useful instrument for managing the development of organizational processes. Subsequently, a conceptual model is proposed that spells out the role of PM in influencing the evolution of routines. The paper closes with a brief discussion and outlines a number of possible avenues for further research based on the proposed model. Action and Representation in Organizational Routines The concept of the organizational routine fully entered the field of management research after the seminal work of Nelson and Winter (1982). In this contribution, the authors gave a broad definition of organizational routines, which included organizational processes whose complexity varied from simple operational routines to revisions in the corporate strategy. The authors noted that the structure of organizational routines could be conceived of as a hierarchy: while some routines play an operational role, other—higher-order—routines perform an organizing function. A complete set of processes then determines organizational boundaries at any given point in time. Nelson and Winter (1982) noted that these organizational processes of different order evolve in response to performance feedback. If the feedback received after the execution of a routine indicates that the performance is no longer satisfactory, the organization initiates a “routine-guided, routine-changing” process of search (Nelson and Winter, 1982: 18). As a result of this search, routines adapt to the new environmental conditions. In this sense, organizational routines are remarkably similar to performance programs (March and Simon, 1963), which are learned routinized responses of organizational actors, or groups of actors, to the problems presented by the external environment. Similar to routines, performance programs incorporate a certain degree of discretionary action, which allows them to evolve in response to the changing demands of the environment. This problem-centered search that underscores the evolution of performance programs is a central characteristic of the decision-making process (Simon, 1979) and is triggered when the appropriate 2 performance feedback is received (March and Simon, 1963; Cyert and March, 1963). Performance feedback is the mechanism through which an organization learns about the adequacy of its performance and which triggers the change in routines (Cyert and March, 1992). Although the view of routines put forward by these scholars was aimed primarily at explaining stability, continuity and repetitiveness, subsequent research made considerable progress in understanding and explaining the dynamic aspects of routines (e.g., Pentland and Rueter, 1994; Feldman, 2000; Feldman and Pentland, 2003) and subsequently applying them to the study of organizational change (e.g., Tranfield and Smith, 1998; Zellmer-Bruhn, 2003; Bresnen et al., 2005). As Becker et al. (2005: 776) note, routines “…are fundamental to understanding change partly because they provide a basic definition of what change ‘really is’ at the organizational level”. It is this definition of change-through-routines that is crucial for the argument that underlies the model presented in this paper. Following the work of Nelson and Winter and behavioral theorists, the concept of organizational routines evolved to incorporate two meanings: routines as behavioral patterns and routines as cognitive regularities. In other words, while for some researchers organizational routines represent primarily recurrent patterns of behavior (e.g., Nelson and Winter, 1982; Teece et al., 1997; Edmondson et al., 2001), others understand it as mental rules or heuristics (e.g., Simon, 1976; Cohen, 1991). Similar to this is the distinction between the ostensive (an abstract concept) and the performative (a concrete action) definitions of routines proposed by Feldman (2000). Becker (2005b) uses the terms “representation” and “action” to make the distinction between the understanding of routines as rules and as concrete observable patterns of behavior. “Cognitive and behavioral”, “representation and action”, “ostensive and performative” are different terms that have been used to describe the key distinction between the two ways in which organizational routines can be conceptualized. Other ways of understanding routines have been suggested. The most notable of these is the view of routines as tendencies or dispositions to express certain behaviors (Hodgson, 2003; Hodgson and Knudsen, 2004), which, as Becker (2005 a, b) states, reflects the deepest ontological level of existence of routines. However, it is the distinction between the understanding of routines as abstract rules and concrete behavioral patterns that underlies most of the current research examining the organizational role of routines. This distinction is very useful for understanding the nature and dynamics of change through organizational routines. One of the most notable pieces of research that shed light on this issue is Feldman’s (2000) study of organizational change in a university housing department. On the basis of empirical observations, she concludes that change in routines can be conceptualized as continuous iterations between reflection and action of individual agents involved in the execution of a routine. Agency is thus a central element of the evolution of organizational routines, and the agents’ cognitive and behavioral activity is the force powering the evolution process. Routines change as the result of “people doing things, reflecting on what they are doing, and doing different things (or doing the same thing differently) as a result of the reflection” (Feldman, 2000: 625). In the process of such a change, both the cognitive models and the behavioral patterns evolve, leading to the full adaptation of a routine to the new conditions. Extending this idea, Feldman (2003) argues that the distinction between the ostensive and performative levels lends an insight not only into the dynamics of change, but also into the mechanism of preserving stability in organizational routines. She argues that the ostensive dimension of a routine may be reinforced by the agents 3 who take into consideration a number of organizational factors in making a conscious decision as to whether or not to bring about the change in behavior (see Espedal, 2006 for an example of such factors albeit in a somewhat different context). In this model of evolution of organizational routines, not only are the ostensive and the performative levels conceptually distinct (Becker, 2005b), but also neither of these levels of activity is superior to the other. In order to adjust the routine so as to generate sustainable performance adequate to the new task at hand, both the mental model and the corresponding pattern of behavior need to adjust. It would be misleading to state that in this process of adjustment, one level of a routine leads the other. Rather, the routine evolves through the interaction of agents’ mental models and their behavioral manifestations (Feldman 2003; Feldman and Pentland, 2003). Both of these levels depend on each other for execution but at the same time are open to unpredictable autonomous variations. The continuous interaction between these levels determines the evolution of the routine. Feldman (2000) compares this process to Argyris’ (1976) concept of single-loop and double-loop learning and Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) knowledge creation process. Empirical work on this model of evolution of routines is scarce. The most notable application of this framework was made by Huberman (2001), although he did not refer to it explicitly. He modeled the process of organizational learning as creation of new or modified routines, where routines were assumed to be stable patterns of behavior. The results of his study suggest that if new action patterns are created faster than the decision rules are updated, the rate of improvement in the system’s performance decreases. In terms of the characteristics of organizational routines discussed earlier, this result may support the proposition that in order to achieve optimal performance, changes in behavioral patterns must be balanced by the corresponding changes in cognitive rules. In summary, the concept of organizational routines provides a useful perspective for investigating the nature of change in organizational processes. While performance feedback triggers the change in organizational routines, the change itself is powered by the agents who are involved in the execution of the routine. The nature of this change is best understood as taking place through continuous iterations between the two levels of routines: cognitive regularities and behavioral patterns. Neither of these leads the other. Rather, routines evolve through the interaction between action and reflection, both of which need to be balanced in order to produce optimal performance. Management Control and Performance Management The factors that make PM an effective instrument for influencing the development of organizational routines can be found in the roots of the contemporary PM research. These roots lie in the fields of accounting (Franco-Santos and Bourne, 2005) and management control systems (Otley, 2003). It has been argued that all the major achievements in accounting were accomplished by the early 20th century (Johnson and Kaplan, 1987) and that accounting practices had lost their relevance to business reality, becoming more of an obstacle than an enabler of effective PM (Kaplan, 1984; Johnson and Kaplan, 1987). New accounting frameworks, such as activity-based costing (Cooper, 1988), were put forward to address this limitation and received some success. However, it has been noted that this success could be attributed not so much to the replacement of the old accounting frameworks by a new paradigm of managing performance, but to the fact that the new methods delivered their benefits indirectly – by stimulating the debates about the drivers of performance and encouraging organizational change (Neely et al., 1995). 4 The issue of control occupies a central place in management literature. It traces its history to the work of Taylor (1911), who saw it as a prerequisite to achieving operational efficiency, and Fayol (1949), who considered it to be one of the five functions of management. Traditionally, control was seen as a function that ensured that business processes remained aligned to the organization’s business objectives. As late as in the 1960s, management control was still defined as “…the process by which managers ensure that resources are obtained and used effectively and efficiently in the accomplishment of the organizational objectives” (Langfield-Smith, 1997: 208). The limitation of this view of control as a coordinating activity fuelled the development of research on management control systems (MCS). In an early study of management control systems, Flamholz et al. (1985) identified four core components of a MCS – planning, measurement, feedback and rewards. They further discussed it in terms of their temporal orientation. While planning takes place before an action is taken, feedback and rewards perform an ex post function – they are triggered by the action. Measurement, however, has a dual role – it can act as an information provider ex post and as a guide for learning ex ante. In its ex post function, it is very similar to feedback in the sense that it communicates to the management the information about the performance of a process that has already been executed. In its ex ante guiding role, however, it is prescriptive in nature - it can focus organizational attention on critical areas before any action is taken. It helps to create the goals towards which the performance will gravitate. The distinction between these two functions is instrumental in understanding the effects of measurement on organizational routines. Routines, as it was mentioned before, can incorporate diverse information in the process of their development, and the way in which the information is “fed into” routines can affect this process. The ex ante and ex post functions of measurement offer two distinct ways of generating this information – by providing an input into the routine before it is executed and by producing the feebdback about its historical performance. Later research in MCS addressed this distinction explicitly and incorporated both functions of measurement into the discussion of management control. Schreyogg and Steinman (1987) introduce the term “feedforward” that corresponds to the ex ante function of measurement and is used to differentiate this function from the traditional ex post feedback effect. Broadly, feedforward refers to the data generated and communicated by performance measures when the latter are used to inform an action before it is taken. Others note that feedforward is preventive in nature and can be used to anticipate threats and lead change (Morgan, 1992) and that it is an autonomous management function that allows management to make steering decisions (Preble, 1992). Simons (1994, 1995) provides the most comprehensive model of a management control system that builds on these propositions and is empirically tested. His idea of diagnostic and belief control systems reflects the use of control in its feedback or information-providing function, while interactive control systems are seen as performing the feedforward function allowing prescriptive actions and leading the development of new behavior in key areas. A similar trend towards incorporating explicitly both functions of measurement can be observed in PM literature. Performance measurement has always been a major instrument of PM, as it provides and integrates all information relevant for making decisions related to the task of managing performance (Bititci et al., 1997). The early contributions in the field of PM thus focused on performance measurement frameworks and pursued the objective of ensuring the alignment between an organization’s strategy and the measures it uses (Eccles, 1991; Lynch and Cross, 1991; Kaplan and Norton, 1992, 1996; Neely et al., 1995). The behavioral 5 impact of measurement was discussed only in terms of eliciting behavior consistent with the intended strategy (Neely et al., 1995; Neely, 1999). In most of these early studies, measurement was used in its feedback function, providing the management with the information necessary to challenge the assumptions underlying the organization’s business model. However, more recent contributions reflect the use of measurement in its feedforward role, where measures are used to prescribe learning domains and stimulate learning in strategically important areas and where processes are allowed to evolve without being fully predetermined by the management (e.g., Kerssens-van Drongelen and Bilderbeek, 1999). Contemporary PM thus encompasses both ways of using measures – as feedback-generating devices that provide information after an event takes place and as communication devices that are used to prescribe the domains of development a priori. Besides the useful distinction between the feedback and feedforward roles of management, another aspect of performance measurement is important for creating a model of the impact of PM on organizational routines. Recent contributions to the PM field, including both qualitative (e.g., Johansson et al., 2001a; Askim, 2004; Vaivio, 2004) and quantitative (e.g., Chenhall, 2005) studies, demonstrated that PM often delivers its benefits indirectly – not simply by encouraging behavior consistent with the determined strategy, but rather by initiating and stimulating the debates about the factors that determine organizational performance. This aspect of PM echoes the insight into the benefits of activity-based costing mentioned earlier and is most pronounced in the stream of PM literature devoted to the measurement of intangibles. Mouritsen (1998) and Johansson et al. (2001 a, b) note that the primary value of measuring intangibles lies not in the accurate estimation of their value, but in stimulating the process of discovering the drivers of organizational performance through the localized search triggered by measurement. In the process of designing objective measures for the resources and processes that are inherently difficult to quantify, the subjective perceptions of such resources and processes surface and become the object of analysis and discussion, during which learning takes place. The existing mental models are projected onto the existing patterns of behavior in an attempt to form an agreed-upon model of organizational performance drivers that could subsequently be measured. This process echoes the dynamics of search that underlies the change in routines discussed earlier. Non-financial measures are particularly powerful in stimulating this search (Vaivio, 2004). Measurement thus intensifies the iterations between action and reflection in organizations. The relationship between measurement and the evolution of organizational routines in not unidirectional, of course. The change in the mental models and the patterns of behavior that takes place as a result of PM efforts in turn influences the process of measurement. De Loo (2006) notes that changes in routines caused by the measurement-fuelled debates become incorporated into the structure of organizational processes, thus becoming higher-order routines. Kloot (1997) points out that management control systems produce the learning environment, in which they cannot but undergo changes themselves. These changes subsequently become a part of new structures and systems and can ultimately lead to the change in organizational boundaries. This parallels the most recent contributions to the field of PM, which find that performance measurement processes can be viewed as a mechanism powering organizational change (Bourne et al., 2003) and that PM systems are deeply embedded in organizational processes and involve a number of individual and collective behaviors (Neely and Bourne, 2000; Kennerley and Neely, 2002, 2003). Summarizing the argument put forward in this section, it can be said that PM affects changes in organizational processes through performance measurement. The performance 6 measurement process affects organizational development by fuelling the constant interaction between reflecting on the performance and altering organizational behaviors and processes, including the measurement process itself. By stimulating the iterations between action and reflection, it intensifies the search for a better match between the mental models of organizational performance and the corresponding patterns of behavior. Two particular elements of the performance measurement process that allow it to be used as a tool of influencing this interaction can be identified from the management control systems literature. Feedback acts as an ex post information-providing mechanism communicating the performance data after an event takes place. The feedback function of measurement is necessary for the evaluation of past performance. Feedforward, on the other hand, is the mechanism for communicating performance priorities ex ante in order to provide guidance for the evolution of mental models and behavioral patterns. Performance Management and Evolution of Organizational Routines In this section, the conclusions drawn earlier are synthesized into a model that explains the effect performance measurement has on the interaction and evolution of organizational cognitive rules and patterns of behavior. Graphically, this model is represented in Figure 1. current organizational boundaries measures of routines (feedback) representation Performance Feedforward from management; feedback; Routines Intensification Intensification action measures of routines (feedback) current organizational boundaries Figure 1. Effects of PM on organizational routines. Organizational processes are understood as routines, which in turn are conceptualized as existing on two levels – action and representation. Changes in routines are described by iterations between these levels. Depending on the way in which performance measurement is used, it affects this process in three distinct ways. When measurement is used in its feedback-generating function, measures communicate the results of the past execution of the routine and indicate whether its performance is adequate to meet the demands of the environment. If such measures indicate a discrepancy, they essentially indicate the necessity to change the routine. As such, measures act as triggers in the process of change in the organizational routines, initiating the process of matching and adjusting existing patterns of behavior and their representations. When measurement is used in its feedforward function, it can affect the direction of the change after it was triggered. In this role of guiding the search, performance measurement can influence the aspects of the routines that undergo change and – more importantly – the balance between 7 changes at the representational and behavioral levels of the organizational routines. In other words, once the change is triggered, it can be guided, and measurement in its feedforward function accomplishes this objective. Finally, regardless of the role that measurement assumes, it makes another contribution to the process of iterations between the representational and the behavioral levels of organizational routines – it intensifies these iterations. As described earlier, measuring organizational processes forces the search for the understanding of existing mental rules and behavioral patterns and stimulates the process of adjusting them in order to respond to the new demands of the environment. Thus, the measurement process itself intensifies the change in the routines precisely through stimulating the interaction between mental models and behavioral patterns. It also has to be noted that in order for this model to be complete, there needs to be an additional smaller feedback loop that would allow management to see where and whether the changes in the routines take place and modify the measurement process accordingly. This feedback is provided by measures of organizational routines, where measurement performs an ex post feedback-generating role. A preliminary classification of related measures of organizational routines is reported elsewhere (Pavlov and Bourne, 2007). As noted earlier, this feedback may also lead to the adjustment of the performance measurement process itself. Discussion and Avenues for Further Research The model presented above is a conceptual model that aims to describe and explain the impact of performance measurement on the evolution of organizational processes. This evolution takes place through the interaction of agents’ mental models and corresponding patterns of behavior. Performance measurement, being a key instrument of PM and offering a number of distinct ways of affecting this interaction, can thus be a tool for initiating, leading and stimulating the evolution of organizational processes. The model responds to several key issues discussed in the opening section of this paper. First, by virtue of employing organizational routines as one of its core constructs, it provides a rich organizational context and a solid theoretical foundation that are lacking in the PM literature. As it was mentioned earlier, the PM field is facing the challenge of using performance measurement systems to manage organizational performance in its full complexity, and no theoretical perspective is as suitable and provides as deep an insight into the relevant issues as that of organizational routines. When organizational processes become the key object of PM initiatives, it is necessary to clarify two key issues: first, what these processes are and how they are related to organizational performance and, second, how they could be affected. The model presented above draws on the insights from the organizational routines literature to address the former issue and on the PM literature to respond to the latter one. As such, it is a model that explains the impact of PM on organizational processes, which responds to the contemporary challenges in the PM field. While the argument laid out in the preceding paragraph describes the contribution of the organizational routines literature to the PM research, the model also suggests that further study of routines can likewise benefit from the insights of the PM field. Generally operational and applied by nature, the PM field has accumulated vast experience with analyzing the concrete methods of using performance measurement to affect performance (e.g., devising and balancing measures (e.g., Ittner and Larcker, 1998; Melnyk et al., 2004) or evaluating their impact on performance (Ittner et al., 2003)). Through its roots in the management 8 control systems research, it has also described the information-providing mechanism that underlies this effect. As such, performance measurement is a relatively well-operationalized tool for affecting organizational dynamics, and therefore is expected to be extremely useful in designing empirical studies of organizational routines. The main implications for further research likewise stem from the interdisciplinary nature of the model. Some of the relationships that make up the structure of the model have been empirically tested – most notably, the trigger effect of performance feedback demonstrated by behavioral theorists and the ex ante effect of feedforward described in the works of MCS scholars culminating in Simons’ (1994, 1995) system of levers of control. However, pulling these findings together and adopting an organizational routines perspective, the model permits asking more and deeper questions about the ways in which PM can be used as an instrument for managing change. These questions will have to be answered empirically. Organized by the function of measurement described earlier, they make up the empirical research agenda offered by the model. As far as the feedback effect of measurement is concerned, the trigger effect and the subsequent search leading to the modification of the routine are well-documented. However, in order for measurement to become an effective instrument for changing organizational routines, its relative impact on the two levels of existence of routines needs to be evaluated. Performance measurement in the wider sense has the power to trigger change in both cognitive models and behavioral patterns. This means that balancing measures to affect both as well as understanding which one should be the primary focus of measurement in which context is necessary for an informed use of performance measurement as an instrument of change. This can perhaps be taken forward by the stream of PM literature examining cognitive mapping and the design of performance measures. Another question pertaining to the feedback effect of measurement is the question of whether the difference in routines’ responsiveness to the effect of feedback can be explained by the dynamics of interaction between the ostensive and the performative dimensions of organizational routines. If either of these dimensions is considerably more stable than the other or the link between them is impaired, will the effect of feedback from performance measures be sufficient to trigger change in the routine? Any PM initiative encounters cases in which existing organizational processes resist change when the new behavior is incentivized without considering the strength of the mental model underlying such processes and vice versa. Whether this question could be answered through the dynamics of iterations between the ostensive and the performative dimensions of routines needs to be evaluated empirically. The feedforward effect of measurement offers even richer and more interesting avenues for further research. First, performance measurement in its feedforward function may determine the routines through which learning takes place. If it is prescriptive in nature and thus drives localized change, it can be an instrument of focusing attention on particular organizational routines. Second, by virtue of possessing tools for affecting both behavior and cognition, performance measurement (again, in its ex ante, prescriptive function) must be able to influence the ostensive and the behavioral level of organizational routines selectively. Third – although at this point it is admittedly speculative – if performance measurement can influence decisions ex ante and has a number of well-operationalized tools, then once the iterations between cognitive and behavioral level of a routine are triggered, it can determine which effect will prevail (i.e., whether the adjustment will take place through changes in mental 9 models or alterations in behavior). These questions stem from the relationships proposed in the framework, and to answer them, more empirical work is necessary. Finally, as far as the intensification effect of measurement is concerned, the model suggests two major questions that need to be answered. First, the existence of the effect itself needs to be validated within the organizational routines perspective. In other words, it remains to be seen whether the process of performance measurement does indeed affect the intensity of the iterations between adjustments on the representational and the behavioral levels of routines, and hence the intensity of change in the routines. Second, if the effect does exist, the question is whether the intensity of such iterations depends on whether performance measurement is used in its feedback or feedforward role. Again, these questions need to be answered empirically. Performance management can be an effective tool for guiding organizational change by affecting the development of organizational processes. However, in order to understand how this potential can be realized, it is necessary to explain the mechanics of its functions. This paper offers a step towards this goal by integrating the relevant findings from a diverse range of literature domains to propose a model that explains the effects of PM on organizational routines and by outlining an agenda for research that can advance our ability to understand the ways in which change in organizational processes can be managed effectively. 10 REFERENCES Argyris, C. 1976. Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision making. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21: 363-375. Askim, J. 2004. Performance Management and Organizational Intelligence: Adapting the Balanced Scorecard in Larvik Municipality. International Public Management Journal, 7: 415-438. Becker, M. C. 2005a. A framework for applying organizational routines in empirical research: linking antecedents, characteristics and performance outcomes of recurrent interaction patterns. Industrial & Corporate Change, 14(5): 817-846. Becker, M. C. 2005b. The concept of routines: some clarifications. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 29: 249-262. Becker, M. C., Lazaric, N., Nelson, R. R., and Winter, S. G. 2005. Applying organizational routines in understanding organizational change. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14: 775-791. Bititci, U. S., Carrie, A. S., & McDevitt, L. 1997. Integrated performance measurement systems: a development guide. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 17(5): 522-534. Bourne, M., Neely, A., Mills, J., and Platts, K. 2003. Why some performance measurement initiatives fail: Lessons from the change management literature. International Journal of Business Performance Management, 5(2,3): 245. Bresnen, M., Goussevskaia, A., & Swan, J. 2005. Organizational routines, situated learning and processes of change in project-based organizations. Project Management Journal, 36(3): 27-41. Chenhall, R. H. 2005. Integrative strategic performance measurement systems, strategic alignment of manufacturing, learning and strategic outcomes: an exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30: 395-422. Cohen, M. D. 1991. Individual learning and organizational routine: emerging connections. Organization Science, 2(1): 135-139. Cooper, R. 1988. The rise of activity-based cost systems: part I - what is an activity-based cost system? Journal of Cost Management, 45-54. Cyert, R. M., and March, J. G. 1963. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Cyert, R. M., and March, J. G. 1992. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. De Loo, I. 2006. Action and organizational learning in an elevator company. The Learning Organization, 13: 204-214. Eccles, R. G. 1991. The Performance Measurement Manifesto. Harvard Business Review, 11 69(1): 131-137. Edmondson, A. C., Bohmer, R. M., and Pisano, G. P. 2001. Disrupted Routines: Team Learning and New Technology Implementation in Hospitals. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46: 685-716. Espedal, B. 2006. Do Organizational Routines Change as Experience Changes? Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 42(4): 468-490. Fayol, H. 1949. General and Industrial Management. London: Pitman. Feldman, M. S. 2000. Organizational routines as a source of continuous change. Organization Science, 11: 611-629. Feldman, M. S., and Pentland, B. T. 2003. Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48: 94-118. Flamholtz, E. G., Das, T. K., and Tsui, A. S. 1985. Toward an integrative framework of organizational control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10: 35-50. Folan, P., & Browne, J. 2005. A review of performance measurement: Towards performance management. Computers in Industry, 56 (7): 663-680. Franco-Santos, M., and Bourne, M. 2005. An Examination of the Literature Relating to Issues Affecting How Companies Manage Through Measures. Production Planning and Control, 16: 114-124. Hodgson, G. M. 2003. The mystery of the routine: The Darwinian Destiny of An Ecolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Revue Economique, 54: 355-384. Hodgson, G. M., & Knudsen, T. 2004. The complex evolution of a simple traffic convention: the functions and implications of habit. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 54(1): 19. Huberman, B. A. 2001. The Dynamics of Organizational Learning. Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 7: 145-153. Ittner, C. D., & Larcker, D. F. 1998. Innovations in Performance Measurement: Trends and Research Implications. Journal of Management Accounting Research , 10: 205-238. Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F., & Randall, T. 2003. Performance implications of strategic performance measurement in financial services firms. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 28(7/8): 715. Johanson, U., Martensson, M., and Skoog, M. 2001a. Measuring to understand intangible performance drivers. European Accounting Review, 10: 407-437. Johanson, U., Martensson, M., and Skoog, M. 2001b. Mobilizing change through the management control of intangibles. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26: 715733. Johnson, H. T., and Kaplan, R. S. 1987. Rise and fall of management accounting. 12 Management Accounting, 68: 22-30. Kaplan, R. S. 1984. The Evolution of Management Accounting. The Accounting Review, LIX: 390-418. Kaplan, R. S., and Norton, D. P. 1992. The Balanced Scorecard - Measures That Drive Performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1): 71-79. Kaplan, R. S., and Norton, D. P. 1996. Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harvard Business Review, 74(1): 75-85. Kennerley, M., and Neely, A. 2002. A framework of the factors affecting the evolution of performance management systems. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 22: 1222-1245. Kennerley, M., and Neely, A. 2003. Measuring performance in a changing business environment. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 23: 213-229. Kerssens-van Drongelen, I. C., and Bilderbeek, J. 1999. R and D performance measurement: More than choosing a set of metrics. R and D Management, 29(1): 35-46. Kloot, L. 1997. Organizational learning and management control systems: Responding to environmental change. Management Accounting Research, 8(1): 47-73. Langfield-Smith, K. 1997. Management control systems and strategy: A critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22: 207. Lynch, R., & Cross, K. 1991. Measure up-The essential guide to measuring business performance. London: Mandarin. March, J. G., and Simon, H. 1963. Organizations. New York: Wiley. Melnyk, S. A., Stewart, D. M., & Swink, M. 2004. Metrics and performance measurement in operations management: dealing with the metrics maze. Journal of Operations Management, 22(3): 209-218. Morgan, M. J. 1992. Feedforward Control for Competitive Advantage: The Japanese Approach. Journal of General Management, 17 (4): 41-52. Mouritsen, J. 1998. Driving growth: Economic Value Added versus Intellectual Capital. Management Accounting Research, 9: 461-482. Neely, A. 1999. The performance measurement revolution: why now and what next? International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 19: 205-228. Neely, A., and Bourne, M. 2000. Why Measurement Initiatives Fail. Measuring Business Excellence, 4(4): 3. Neely, A., Gregory, M., and Platts, K. 1995. Performance measurement system design: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 15(4): 80-116. 13 Nelson, R. R., and Winter, S. G. 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press. Nonaka, I., and Takeuchi, H. 1995. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press. Otley, D. 2003. Management control and performance management: whence and whither? British Accounting Review, 35: 309-326. Pavlov, A., & Bourne, M. 2007 (forthcoming). Responding to contemporary challenges in performance management: Measuring organizational routines. Proceedings of the 14th International Annual EurOMA Conference, Ankara, Turkey. Pentland, B. T., & Rueter, H. H. 1994. Organizational Routines as Grammars of Action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(3): 484-510. Preble, J. F. 1992. Towards a Comprehensive System of Strategic Control. The Journal of Management Studies, 29: 391-409. Schreyogg, G., and Steinmann, H. 1987. Strategic control: A new perspective. Academy of Management Review, 12(1): 91-103. Simon, H. A. 1976. Administrative Behavior. A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organization (3rd ed.). New York: The Free Press. Simon, H. A. 1979. Rational decision-making in business organizations. American Economic Review, 69: 493-513. Simons, R. 1994. How new top managers use control systems as levers of strategic renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 15: 169-189. Simons, R. 1995. Control in an age of empowerment. Harvard Business Review, 73(2): 8088. Taylor, F. W. 1911. The Principles of Scientific Management . New York: Harper. Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18: 509-533. Tranfield, D., & Smith, S. 1998. The strategic regeneration of manufacturing by changing routines. International Journal of Operations & Production Management , 18(1/2): 114-129. Vaivio, J. 2004. Mobilizing Local Knowledge with 'Provocative' Non-financial Measures. European Accounting Review, 13(1): 39-71. Zellmer-Bruhn, M. E. 2003. Interruptive Events and Team Knowledge Acquisition. Management Science, 49(4): 514-528. 14