REPORT OF THE COUNCIL ON SCIENTIFIC AFFAIRS

advertisement

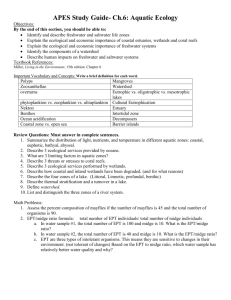

REPORT OF THE COUNCIL ON SCIENTIFIC AFFAIRS CSA Report 9-A-05 Subject: Expedited Partner Therapy (Patient-Delivered Partner Therapy) (Resolution 820, I-04) Presented by: Melvyn L. Sterling, MD, Chair Referred to: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 Reference Committee E (Daniel W. van Heeckeren, MD, Chair) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Resolution 820 (I-04), introduced by the American Association of Public Health Physicians, the American Medical Women’s Association, and the Washington Delegation at the 2004 Interim Meeting and referred to the Board of Trustees, asks: That our American Medical Association (AMA): (1) encourage state licensing boards, medical societies, health and malpractice insurance carriers, and others to consider the demonstrated benefits of Patient-Delivered Partner Therapy (PDPT) when evaluating the appropriateness of this practice; (2) encourage continued research on expedited partner treatment (EPT) and other innovative strategies for sexually transmitted infection (STI) control; (3) encourage federal, state, and local governments to fully fund STI control programs; (4) support and encourage efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to identify opportunities for increased use of PDPT; analyze existing and potential barriers to PDPT use; encourage use of PDPT in all appropriate settings; and establish model guidelines and recommendations for implementation of PDPT and other EPT strategies; and (5) notify appropriate medical societies, federal and state agencies, and malpractice carriers of its position on PDPT. This Council on Scientific Affairs report briefly describes our AMA’s current collaborative efforts with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on the issue of expedited partner therapy (EPT) and provides recommendations for consideration by the House of Delegates. DATA SOURCES Our AMA participated in a meeting, Expedited Partner Therapy Stakeholders Consultation, organized by the CDC on March 2-3, 2005. This meeting presented a systematic review of the science of EPT as well as significant background information on the issues that need to be considered when implementing EPT. INTRODUCTION EPT has been discussed and used by health care professionals over the past decade.1,2 EPT involves enabling treatment, without a prior examination, of sex partners of individuals diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease (STD). Patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) is an extension of EPT in that the patient is asked to deliver the treatment to the sex partner. Currently, the focus of EPT is on the sex partners of those persons infected with gonorrhea or Chlamydia because of the significant public health burden of these diseases and the relative ease of treatment with antibiotics. Thus, EPT can be carried out by physicians giving medication to patients for their partners, giving prescriptions to patients for their partners, or providing “use as needed” prescriptions. Public health CSA Rep. 9 -- A-05 — page 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 professionals can also deliver medication during partner follow-up interviews with or without collecting morbidity data. The rationale for EPT arises from data indicating there is an inability to provide public health staff the assistance and resources they need to contact, notify, and bring to treatment many sex partners of persons infected with STDs. Indeed, in 1998 only 17% of gonorrhea and 12% of Chlamydia patients received partner-notification services.3 CURRENT SCIENTIFIC DATA ON EXPEDITED PARTNER THERAPY While limited, sufficient good-quality studies exist to indicate that EPT can not only reduce the incidence of chlamydial infections,4 it can also significantly reduce the reinfection rates of patients with chlamydial infection.5-7 EPT has been shown to be more effective than patient self-referral (whereby the patient is asked to notify partners about exposure and encourage them to seek treatment) in ensuring follow-up with the sex partner.8 Similarly, a randomized, controlled study by Schillinger demonstrated reduced incidence of chlamydial infection in patients receiving EPT as compared to patients in the self-referral arm.9 Studies also indicated significant reduction in gonorrheal reinfections and significant reduction in symptomatic urethritis due to Neisseria gonorrhea following EPT.5 Data also indicate that EPT improves the frequency at which the partner receives notification of his/her potential exposure and the frequency of treatment.5,10 Additionally, those who received EPT are more likely to ensure that their partner completes the treatment. Data also indicate that those participating in EPT are more likely to improve sexual behaviors (eg, reduce frequency of unprotected sex). Accordingly, it appears that with respect to medical science, EPT is indicated for partners of those diagnosed with gonorrheal or chlamydial infections. Since 2001, medical professionals in California have been allowed by law to provide patients diagnosed with Chlamydia infection with antibiotics to deliver to their sex partners. While preliminary, data emerging from California support published findings and indicate that most participating physicians feel that EPT protects patients from reinfection and that EPT helps provide better care for patients with Chlamydia. Consequently, the CDC is currently engaged in a major effort to improve the use of EPT in the United States. As part of this process, the CDC has already conducted a systematic review of the scientific evidence on EPT in order to produce an official guidance on the implementation of EPT. From a cost-effectiveness perspective, while the data are limited, it appears EPT is at least comparable if not less costly than standard referral in terms of cost per index patient and cost per partner treated; however, more research is indicated. A study by Postma suggests that partner therapy reduces net costs per outcome averted by about 50% and sensitivity analyses indicate that even when assumptions are varied, cost-effectiveness was demonstrated. 10 However, most participants in the stakeholders’ meeting agreed that while EPT should be an option available to physicians in their “toolbox” for combating chlamydial and gonorrheal infections, the primary goal is still to get the partner of the index patient to a physician for examination. This reflects concerns about the potential loss of the partner to actual physician follow up due to EPT, which may result in lost opportunities to identify potentially more serious medical conditions associated with chlamydial and gonorrheal infections, such as pelvic inflammatory disease. CSA Rep. 9 -- A-05 — page 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 BARRIERS TO THE IMPLEMETNATION OF EXPEDITED PARTNER THERAPY A significant portion of the CDC meeting focused on discussing barriers that must be overcome to facilitate EPT in the United States. These range from funding mechanisms to liability. Some of the more important barriers are summarized below. Funding Mechanisms Some public health clinics and other similar providers will likely pay the direct and administrative costs of providing EPT, especially if the treatment is delivered through the index patient. However, the sustainability of such funding is uncertain as burdens on state public health funding continue to increase. In the private care setting, the patient, the sex partner, or their insurers will be responsible for the cost of EPT, potentially creating barriers in some situations. While the data indicating reduced risk of persistent or recurrent gonorrhea and chlamydial infections and their accompanying complications will prompt some health maintenance organizations to cover EPT, others will decline to cover it for logistical and administrative reasons, or due to liability concerns. Cost of EPT Cost is of particular concern for already under-funded public health departments and in this situation, the benefits derived from EPT will have to balanced by the trade-offs with other prevention strategies, such as primary screening of women, expansion of screening to underserved populations of women, screening programs for males, and rescreening of persons treated for either chlamydial or gonorrheal infection. However, it is likely that the actual expenses of EPT are modest relative to the total costs incurred in the diagnosis and management of patients with treatable STDs, and in relation to the potential to prevent complications and curtail the spread of infection. Legality of EPT For EPT to become reality in California, a specific exception to the state’s Medical Practice Act had to be enacted by the state legislature. This reflects the fact that providing a prescription drug to a patient with whom the clinician lacks an established physician-patient relationship may not be legal in all settings and may be considered a breach of medical ethics.11 Regardless of the actual legal status of EPT, perceived illegality is another significant barrier to its implementation. As is evidenced by experience in California, Tennessee, and Washington state, changes may have to be made to grant physicians the option of EPT for their patients diagnosed with Chlamydia or gonorrhea. As suggested earlier, preliminary data from California indicate that the removal of legal barriers improves utilization of EPT. STD Co-morbidity in Partners As noted above, EPT may involve missed opportunities for diagnosis and treatment of STDs that would be detected by personal examination of the partners. It is clear that where traditional partner management approaches are available to the physician, EPT should be deemphasized. However, this risk of delayed diagnosis and undertreatment may be balanced by the improved rates of notification and treatment of sex partners associated with EPT. Regardless, all physicians should be aware of these caveats before considering EPT for their patients, and partners should be urged to seek followup examinations after EPT. CSA Rep. 9 -- A-05 — page 4 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Concern is also expressed about the potential missed opportunities for prevention counseling of partners receiving EPT. However, there are no data to quantify the prevention efficacy of such counseling, or to document that the prevention benefit of an interview outweighs that which would be possible via the use of educational literature that can accompany EPT. Liability Concerns Physicians may encounter litigation in the event of adverse outcomes due to EPT. State law may also prohibit prescribing to patients with whom a physician has no established relationship. However, as the CDC continues to educate on the value of EPT as an additional tool to treat STDs, it is likely that this concern will decrease as EPT becomes a legally acceptable community practice. On the reverse side, liability concerns also exist should it be argued that a physician failed to prevent reinfection of his/her patient by failing to offer EPT to the patient’s partner. The CDC acknowledges the value of establishing EPT as an accepted community standard of care and intends to use its planned guidance to accomplish this. CURRENT STATUS OF THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION EXPEDITED PARTNER THERAPY GUIDANCE The CDC has stated its intention to issue two documents on EPT. These documents will reflect the extensive literature reviews and expert opinion/stakeholder consultations that have been conducted. The first document will be a “white paper” highlighting the scientific data supporting EPT and the associated risks and benefits of adding this tool to the physician’s options to reduce the incidence of Chlamydia and gonorrhea. A second, less scientific, “implementation guidance” will then follow the white paper to assist states to implement the legislation, policies, and education necessary to establish EPT as an acceptable and available practice. At this time, the CDC anticipates that the first “white paper” will be available for stakeholder review in Fall 2005. CONCLUSIONS The CDC has already expended significant effort in researching the scientific evidence for or against a more widespread implementation of EPT. It appears from the presentations and discussions at the CDC-sponsored EPT stakeholder meeting held in Atlanta on March 2-3, 2005, that the medical and scientific evidence supports the use of EPT in treating the sex partners of patients who have been diagnosed with either chlamydial or gonorrheal infections. However, numerous barriers remain to be addressed for EPT be successfully implemented throughout the United States. Our AMA should remain engaged with the CDC as it completes its guidance on the implementation of EPT. Following official publication of the guidance, our AMA can review and offer its support for the guidance recommendations at that time. CSA Rep. 9 -- A-05 — page 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 RECOMMENDATIONS The Council on Scientific Affairs recommends that the following statements be adopted in lieu of Resolution 820 (I-04), and that the remainder of this report be filed: 1. That our American Medical Association continue to work with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as it prepares its “white paper” on expedited partner therapy (EPT) and its follow-up guidance on the implementation of EPT. (Directive to Take Action) 2. That our AMA review and then support, as appropriate, the final documents on expedited partner therapy as issued by the CDC. (Directive to Take Action) 3. That our AMA encourage continued research into benefits and potential adverse outcomes that might be associated with the use of EPT to treat sex partners of those diagnosed with either chlamydial or gonorrheal infections. (Directive to Take Action) Fiscal Note: $3,000, to continue to participate in CDC stakeholder meetings on EPT. CSA Rep. 9 -- A-05 — page 6 REFERENCES 1. Golden MR, Whittington WL, Gorbach PM, Coronado N, Boyd MA, Holmes KK. Partner notification for chlamydial infections among private sector clinicians in Seattle-King County: a clinician and patient survey. Sex Transm.Dis. 1999;26:543-547. 2. Hogben M, McCree DH, Golden MR. Patient-delivered partner therapy for sexually transmitted diseases as practiced by U.S. physicians. Sex Transm.Dis. 2005;32:101-105. 3. Golden MR, Hogben M, Handsfield HH, St Lawrence JS, Potterat JJ, Holmes KK. Partner notification for HIV and STD in the United States: low coverage for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and HIV. Sex Transm.Dis. 2003;30:490-496. 4. Klausner JD, Chaw JK. Patient-delivered therapy for chlamydia: putting research into practice. Sex Transm.Dis. 2003;30:509-511. 5. Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N.Engl.J.Med. 2005;352:676-685. 6. Ramstedt K, Forssman L, Johannisson G. Contact tracing in the control of genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Int.J.STD AIDS. 1991;2:116-118. 7. Kissinger P, Brown R, Reed K, et al. Effectiveness of patient delivered partner medication for preventing recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm.Infect. 1998;74:331-333. 8. Nuwaha F, Kambugu F, Nsubuga PS, Hojer B, Faxelid E. Efficacy of patient-delivered partner medication in the treatment of sexual partners in Uganda. Sex Transm.Dis. 2001;28:105-110. 9. Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: a randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm.Dis. 2003;30:49-56. 10. Postma MJ, Welte R, van den Hoek JA, van Doornum GJ, Jager HC, Coutinho RA. Costeffectiveness of partner pharmacotherapy in screening women for asymptomatic infection with Chlamydia Trachomatis. Value.Health. 2001;4:266-275. 11. Golden MR, Anukam U, Williams DH, Handsfield HH. The legal status of patient-delivered partner therapy for sexually transmitted infections in the United States: a national survey of state medical and pharmacy boards. Sex Transm.Dis. 2005;32:112-114.