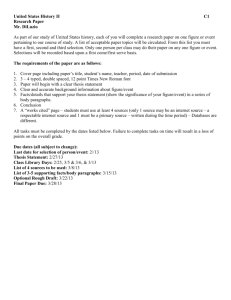

Steps to Completing the Research Paper

advertisement

STEPS TO COMPLETING YOUR RESEARCH PAPER Step One: Choose a Topic Your broad subject has already been assigned. Now you need to narrow your topic to a manageable topic for the space and time you have to work. For topic ideas, you may consult the daily media—radio, television, newspapers, the Internet. Listen carefully to general conversations, for they, too, may suggest topics. Choose a topic that’s right for you and for your assignment. Choose a good topic that has these characteristics: Interesting: A good topic holds your interest and that of your audience; it’s something you want to learn more about. Manageable: You have only a limited amount of time and resources available, so choose a topic you can handle. Worthwhile: Choose something of substance, something that matters. Original: A good topic is not just a rehashing, for instance, of Abraham Lincoln’s childhood. A more original topic might be how the books he read as a boy seem to have influenced his later political decisions. Avoid a topic with these characteristics: Too broad. Avoid a topic that is too broad. The Ice Age is far to broad a topic, but the role of the Ice Age in the formation of the Great Lakes will work. Hieroglyphics is too broad a topic, but how original Egyptian hieroglyphics are protected will work. Too narrow. By contrast, also avoid a topic that is too narrow, one for which little information is available. For example, metric cooking conversions is too narrow; it can be explained in a few sentences or even in a chart. The complexity of national metric conversion, however, has sufficient breadth for a suitable topic. Too factual. A research paper is not merely a recitation, for instance, of the facts of Thomas Jefferson’s life. Finally, choose a topic that you can word in a question, like these: How did Jefferson affect American politics prior to his presidency? How do the Amish differ from the Mennonites? What elements are necessary in a landfill design to protect future generations? Step Two: Do the Preliminary Work Before you get down to serious business, do some preliminary work. In the long run, it will save you hours, maybe even days. The preliminaries consist of three parts: 1. Do some preliminary reading to get background information about your topic. 2. Write a research question that reflects the purpose of your paper. 3. Prepare a working outline. Step Three: Locate Secondary Sources Secondary resources are materials written later about someone or something, like books, and magazine articles. For your purpose, secondary sources are sufficient. Be sure to seek a wide variety of sources. Evaluate your sources to see whether or not the information is accurate and reliable. Step Four: Prepare Bibliography Cards When you have located adequate resources, prepare a bibliography card for each. Use a separate 3 x 5 inch card for each source. If you follow these guidelines, your Works Cited page will be a snap. On each card you must include: Author (last name, first name) Title of the Work. Titles of books and periodicals should be italicized or underlined. Place quotation marks around the titles of articles. Capitalize words in titles correctly. Publishing Information: BOOKS: place of publication, name of publisher, date of publication MAGAZINES: issue date (day, month, year), page numbers, state of publication INTERNET SOURCES: date of publication, URL, date you visited the site Here’s a major tip: If you are unsure how to document a source on your Bib. cards, reference the MLA Style Handbook or visit <Noodles.com>. Another helpful website which provides examples of thesis statements, literary papers, and documentation of sources is www.dianahacker.com. Step Five: Take Notes GENERAL GUIDELINES: Use a separate note card for each idea, even if you write only a few words on a card. Write in ink, only on one side of the card. While you may develop your own form of shorthand, use only abbreviations that will make sense to you later. On every note card, in the upper right corner, write the number, circled, too identify its source. Follow the source number with a hyphen and then the page numbers. On the top line of every note card add a slug—a title that identifies the topic of the note and corresponds to the heading or subheading in your preliminary outline. Avoid Plagiarism! Plagiarism is literary theft, using someone else’s words or ideas as if they were your own. It’s a serious offense, usually with serious penalties attached—like automatic failure for the paper or even the course. Direct Quotations are used when you want to quote a source’s exact words. If you use a source’s exact words and do not put it in quotations, it is considered plagiarism. Paraphrased Notes are a rewording of the original in about the same amount of words. If you do not document where this information came from, this is also considered plagiarism. You must indicate where you receive all of your information in your research paper. Step Six: Write the Final Outline Your final outline should include your thesis statement. You thesis statement is NOT a question. It is a statement. Sort your note cards according to their slugs—those topics that came from your working outline. You may organize your information chronologically, spatially, or in order according to importance. Below is a model of an outline: Thesis Statement: When earth’s citizens recognize wetlands’ values, perhaps they will be more concerned about the protection of those vanishing areas. I. II. III. IV. Definition of wetlands A. Definition by category B. Definition by characteristics C. Definition by law Destruction of wetlands A. Losses 1. Past 2. Continuing B. Causes Effects of destruction A. On plant life B. On animal life 1. Marine creatures 2. Waterfowl 3. Other wildlife C. On water 1. Storage area 2. Filtering system 3. Storm protection D. On biosphere Value to humans A. Economic impact B. Economic controversy C. Resulting efforts Step Seven: Write the Draft Writing the Introduction: Make a conscious effort in your introduction to attract reader interest. Startle the reader with facts and statistics. Use a story or conversation to introduce an event. Explain a conflict or inconsistency. As a provocative question. Use a quotation, adage, or proverb. State your thesis statement in your introduction. Writing the Body Paragraphs: Be sure to document ALL of your sources in your rough draft to keep yourself from plagiarizing in your final draft. Be sure each paragraph has a topic sentence and your details support that topic sentence. Use your note cards to provide the details to support your ideas. Follow your outline. Use transitional words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs to connect ideas within and between paragraphs. Omit any irrelevant material. Writing the Conclusion: Provide a summary. Reach a conclusion. Make an observation/solution. Issue a challenge. OR Refer to the introduction. Step Eight: Revise the Draft Use the following checklist when revising your first draft: Do all of your body paragraphs support your thesis statement? Does the order of my paragraphs make sense to the reader? Are they arranged in some logical order? Did I follow my outline or its revision? Does each paragraph have a topic sentence and details that support that topic sentence? Did I use transitional words and phrases when I change ideas/topics? Have I written grammatically sound sentences, avoiding fragments, run-ons, and redundancies? Is my punctuation correct? Did I capitalize the first letter of every sentence and provide the proper end punctuation? Is my paper interesting? Do I vary my sentence structure and provide valuable information? Did I document ALL of my information in my paper? Step Nine: Prepare the Final Manuscript Use 8x11 white paper. Double-space the entire paper. Maintain one inch margins on both sides. Don’t use a font any larger than 12 point. Indent five spaces for each paragraph. Your first page should contain your name, your teacher’s name, the course title, and the due date. Documentation: Include documentation after every quotation or paraphrase. Example: The stream waters flowing out of such wetlands are “cleaner than most municipally treated water” (Klockenbrink 72) and teem with fish, plants, and birds. Example: Annual wetlands productivity in Georgia’s Alcovy River Swamp equals roughly a $3.1 million impact (Goodwin and Niering 4-7). The Works Cited Page: See teacher provided examples. Be sure to adhere to the format you used on your bibliography cards. Step Ten: Proofread the Paper Proofreading the paper is an exacting task. Allow plenty of quiet time to complete this step. Read every word and sentence carefully, looking for mistakes in spelling, punctuation, and grammar. Check for consistent use of tense and point of view. Most of the time you are going to use present tense and third person point of view. Check all of your information to make sure it is documented correctly. Check that every source listed on your Works Cited Page is also used somewhere in your paper. Check to make sure you have avoided plagiarism.