File - Ms. Bruggers` World History & Geography Page

advertisement

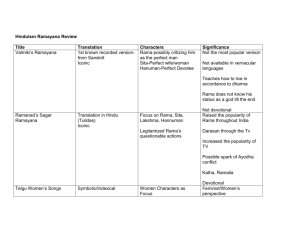

The Story of the Ramayana Briefly (Laura Gibbs, laura-gibbs@ou.edu) So, just to let you know what you are in for, here is a very brief summary of the Ramayana, the adventures of lord Rama. Rama is the son of King Daśaratha, but he is also an incarnation of the god Vishnu, born in human form to do battle with the demon lord Ravana. Ravana had obtained divine protection against other demons, and even against the gods - but because he scorned the world of animals and men, he had not asked for protection from them. Therefore, Vishnu incarnated as a human being in order to put a stop to Ravana. King Daśaratha has three other sons besides Rama. There is Lakshmana, who is devoted to Rama. There is also Bharata, the son of Daśaratha's pretty young wife Kaikeyi, and finally there is Śatrughna, who is as devoted to Bharata as Lakshmana is to Rama. When Daśaratha grows old, he decides to name Rama as his successor. Queen Kaikeyi, however, is outraged. She manages to compel Daśaratha to name their son Bharata as his successor instead and to send Rama into exile in the forest. Rama agrees to go into exile, and he is accompanied by his wife Sita and his brother Lakshmana. When their exile is nearly over, Sita is abducted by the evil Ravana who carries her off to Lanka city (on the island of Sri Lanka). Rama and Lakshmana follow in pursuit, and they are aided by the monkey lord, Hanuman, who is perfectly devoted to Rama. After many difficulties and dangers, Rama finally confronts Ravana and defeats him in battle. What happens after that is a matter of some dispute in the different versions of the Ramayana. Did Rama accept Sita back into his household? Or did he send her away because she had been in the possession of another male? You will see different versions of the ending in the two different editions of the Ramayana that you will read for this class. A Digression About Time In historical terms, the events of the Ramayana are supposed to precede the events of the Mahabharata. The time periods of Hindu mythology are called "yugas," and the world as we know it goes through a cycle of four yugas. Sometimes these four yugas are compared to a cow standing on four legs. In the "Best Age," the Krita Yuga, the cow is standing on all four legs. In the next age, the Treta Yuga, or "Age of Three," the cow is standing on only three legs and is slightly teetering, and so the world is slightly corrupted. In the next age, the "Age of Two," or Dwapara Yuga, there is only half as much righteousness in the world as there used to be, like a cow standing on only two legs. This is followed by the worst age, the Kali Yuga, where there is only one-fourth of the world's original righteousness remaining. As a result, the world of the Kali Yuga has become extremely corrupt and utterly unstable. The cow is standing on just one leg! The events of the Ramayana take place in the Treta Yuga, when the world is only somewhat corrupted. The events of the Mahabharata take place much later, at the end of the Dwapara Yuga, the "Age of Two," when the world is far more grim and corrupt than in Rama's times. The violent and tragic events at the end of the Mahabharata mark the end of the Dwapara Yuga and the beginning of the Kali Yuga, the worst age of the world. We are living in the Kali Yuga, in case you were wondering... The Story of the Mahabharata Briefly In some ways, the entire story of the Mahabharata is an explanation of how our world, the world of the Kali Yuga, came into being, and how things got to be as bad as they are. The Ramayana has its share of suffering and even betrayal, but nothing to match the relentless hatred and vengeance of the Mahabharata. The culmination of the Mahabharata is the Battle of Kurukshetra when two bands of brothers, the Pandavas and the Kauravas, the sons of two brothers and thus cousins to one another, fight each other to death, brutally and cruelly, until the entire race is almost wiped out. The five sons of Pandu, the Pandavas, are the heroes of the story. The eldest is King Yudhishthira. Next is Bhima, an enormously strong fighter with equally enormous appetites. After Bhima is Arjuna, the greatest of the warriors and also the companion of Krishna. The last two are twins, Nakula and Sahadeva. These five brothers share one wife, Draupadi (she became the wife of all five of them by accident, as you will learn). The enemies of the Pandavas are the Kauravas, who are the sons of Pandu's brother, Dhritarashtra. Although Dhritarashtra is still alive, he cannot manage to restrain his son Duryodhana, who bitterly resents the achievements of his cousins, the Pandavas. Duryodhana arranges for his maternal uncle to challenge Yudhishthira to a game of dice, and Yudhishthira gambles everything away, even himself. The Pandavas have to go into exile, but when they return they engage the Kauravas in battle. Krishna fights on the side of the Pandavas, and serves as Arjuna's charioteer. The famous "Song of the Lord," or Bhagavad-Gita, is actually a book within the Mahabharata, as the battle of Kurukshetra begins. When Arjuna faces his cousins on the field of battle, he despairs and sinks down, unable to fight. The Bhagavad-Gita contains the words that Krishna spoke to Arjuna at that moment. The Pandavas do win the battle. Duryodhana is killed, and the Kaurava armies are wiped out. But it is hardly a happy ending. Yudhishthira becomes king, but the world is forever changed by the battle's violence. If you are familiar with the Iliad, you might remember how that epic ends with the funeral of the Trojan hero Hector, a moment which is utterly bleak and sad. The same is true for the Mahabharata. There are many truths that are learned in the end, but the victory, such as it is, comes at a terrible price. From http://onlinecourselady.pbworks.com/w/page/12763819/Online%20Course%20Lady Kalidasa's Life (page 1) (from http://kireetjoshiarchives.com) "Valmiki, Vyasa and Kalidasa are the essence of the history of ancient India", said Sri Aurobindo, "if all else were lost, they would still be its sole and sufficient cultural history." Yet, of the life of these three great poets we know very little. And the three plays and four poems of Kalidasa tell us nothing directly about himself. Even Mallinatha, the great commentator of Kalidasa, who lived in the XIVth century AD is silent about his life. As there was more than one author bearing the name of Kalidasa, the facts about one got mixed with that of the others creating confusing myths about his life story. It is generally believed that Kalidasa was a native of Malava (ancient Avanti) and that he lived in its capital Ujjain (in today's Madhya Pradesh). It appears certain that Kalidasa knew Ujjain well and described the beauty of the city including its river, Kshipra. Yet Kalidasa's works show such a wealth of knowledge about the fauna and flora of different regions that many parts of India, including Bihar, Varanasi, Bengal, Kashmir and Vidarbha have laid claim to the honour of being the birth-place of the poet. For instance an author could remark that Kalidasa, being able to describe a flower of saffron, must have lived in Kashmir. Others said that his description of the Ganges prove that he was a native of Bengal, etc. The date of Kalidasa's birth is also a subject of great debate. The Indian tradition regards Kalidasa as one of the nine ratnas (gems) that adorned the King Vikramaditya's court in Ujjain. But various kings in the history of ancient India called themselves by that title, Vikramaditya meaning "Sun of valour". Some scholars identify this Vikramaditya with the King who defeated the Shakas and established the Samvat era in 57 BC in Ujjain. Some others claim that the Vikramaditya in question is Chandragupta II (c. AD 375-414) of the Gupta dynasty. Various other dates have been proposed, so much so that a book like Kalidasa and His Times could present no less that five different theories, along with their arguments and counter-arguments. In any case, it seems certain that the earliest limit would be the second century BC (as one of Kalidasa's plays Malavikagnimitra mentions some historical events of the Shunga period), and the latest limit would be the seventh century AD (as the name of Kalidasa was found in the Aihole inscription dated AD 634, and also in the Harshacharita of Bana, a court poet of emperor Harsha of Kanauj who reigned from AD 606 to 647). Indian scholarship tends to place Kalidasa earlier in history than Western scholarship. Around this uncertainty, and probably because of it, a number of anecdotes, fanciful stories and legends have grown. Some belong to the Indian tradition, some to the Tibetan, and some to the Ceylonese tradition. It seems that anecdotes and folklores about Kalidasa began to emanate from the sixteenth century onwards. Kalidasa’s Life (page 2) According to some accounts, particularly the Tibetan tradition, Kalidasa was born to Brahmin parents and was orphaned soon after his birth. He was brought up by a cowherd and was so dumb that he would sit on the upper end of a branch of a tree and cut the lower part of it with an axe, the perfect example of an idiot. A wicked man, having been refused by the learned Vasanti, daughter of the king of Varanasi, wanted to take his revenge. He managed through some tricks to have her marry the young boy. After a few days, Vasanti discovered that her husband was an idiot and she ordered him out of the house. According to some stories, Kalidasa then undertook a tapasya and prayed to the goddess Kali. That is how he took the name of Kalidasa, the servant of Kali. The goddess was pleased and conferred on him high poetic genius. Then, a transformed man, he came back to the house. The door was closed. Kalidasa called his wife in Sanskrit: "anaavritakapaatam divaaram dehi" ("open the door") His learned wife was surprised to hear him speak in Sanskrit. She asked : "asti kashchit vaagvisheshah", that is to say: "Has some quality come into your speech?" Then Kalidasa is said to have taken the three words uttered by his wife, respectively asti, kashchit, and vaag, and written three poems, each one starting with one of these words. From asti came Kumarasambhava. From kashchit, Meghaduta and from vaag, Raghuvamsha. We can find stories about Kalidasa in the tradition of Sri Lanka also. A Ceylonese work Parakramabahucharita which is five hundred years-old speak of Kalidasa's friendship with Kumaradasa, ruler of Ceylon, who was himself a good poet. . . Many anecdotes seem fanciful. But the facts that such legends abound testify to the immense popularity of Kalidasa. "Not only these, while travelling in trains and villages of India we find innumerable stories, very amusing and interesting regarding Kalidasa. All these show that Kalidasa does not live only among the scholars of India and abroad but he is equally one of the most beloved and dearest poets even among those who are not all acquainted with his works or who do not even know how to write and read. And Kalidasa perhaps lives as dearly and as lovingly among them as he does in the minds of the erudite scholars."* What seems certain at any rate since it comes from a study of Kalidasa's writings themselves is that the extent of his knowledge was prodigious. He knew the Vedas, the Upanishads, the different Shastras, the epics. He must have travelled extensively in Northern India as he described the different kingdoms with their particular customs, manners and products, their geography, their streams and mountains and valleys. He described the trees, flowers, fruits of many regions. He portrayed the beauty of the Himalayas and the Ganges. He gave precise and minute descriptions of all kinds of birds. He possessed a great knowledge of music both vocal and instrumental. He was expert in three ragas of Indian music. He was familiar with the various strata of Indian society. His keen observation surveyed all sorts and conditions of men, princes and peasants, wise and worldly Brahmanas, fishermen and policemen. In fact his knowledge seems so extensive that some authors saw it fit to give him the title of Sarvajna: the all-knowing. Works: Seven works are attributed to Kalidasa. Out of them, three are plays. . . and four are poems,). There is no external evidence to ascertain the chronology of Kalidasa's works. However, judged on the base of internal evidence, a few remarks have been made, for instance that Ritusamhara seems to be an early work, and that of the three plays Malavikagnimitra must have been the first and Shakuntala the last.