superpower paper project • curriculum

advertisement

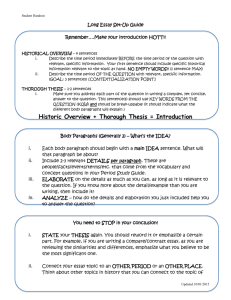

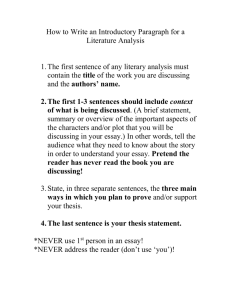

SUPER-POWER ESSAY • CURRICULUM FOR 6th GRADE SALMON BAY MIDDLE SCHOOL © 2003 by Craig Coss BEGINNING THE PROJECT Transition ideas • Ask students if anyone reads comic books, and then ask how many superpowers they know about from comics, film, television, myths, novels, or other stories. (Nathaniel brought up John Henry: a great story.) • Tell a personal story of a real person you heard about, read about, or saw who demonstrated a supernatural “super” power. Looking at Past Superpower Papers • Tell students that last year, every 6th grader wrote an essay—of publishable quality—on what they thought the most useful super-power would be. All of the papers were published and sent to a high school for art students to read, decide which one was persuasively written in their mind, and illustrate. • The superpowers could be yours, a superhero’s, or a belong to a god, goddess, or other supernatural being. But you may only pick one power and argue why that power would be most useful. • Have students volunteer to read a couple of sample essays aloud from last year, so the students get the idea. • Talk about the quality of last year’s writing, if it comes-up and seems natural. Introducing the Project • Hand-out the Super-power Paper Project instructions (with the rubric on the back). • Have students read the various writing phases of the project aloud. • Emphasize that each phase will be done together. Nobody should go home tonight and write an essay. Instead, “We’ll do each phase together as a class, a little bit at a time, until you’ve finished your essay.” PHASE ONE: BRAINSTORM IDEAS • In table groups, students spend ten minutes (time it!) brainstorming as many different super-powers as you can think of. Emphasize that a brainstorm means that no ideas (except, perhaps, clearly silly ones) are left out: just get them all down. • This is always very fun and lively, and some groups pride themselves on collecting many powers. I sometimes tell the class that some groups in the past have thought of over 40 powers in ten minutes. • While students brainstorm, teacher prepares to write “categories of usefulness” on the board (or some other place to display powers) • Ring the 10-minute bell (“Time’s up”) and have each table share with the class an exotic or unusual power that they think no other table might have. • Explain the different levels of usefulness. I like to do this with the students’ input and phrasing: 1) Powers that are useful only (or mostly) to the person who possess them. 2) Powers that help others, or are useful to humanity. 3) Powers that are useful to more than just people, such as nature, animals, and the earth. 4) Powers that are useful for some great cosmic purpose, or truth. • With these headings posted or written on the board, have students write different powers under each heading. In the past, I’ve had one student/table write at a time, and hand the chalk off to someone else at their table. • While this happens, the students at their tables then may either look for a first and second choice, debate which powers would be most useful, and try to decide on a first and second choice (their “back-up” power). Brainstorming Homework • Pick two powers (first choice and your “back-up”) and then brainstorm, on your own, at least twelve uses for each power. (I suggest using one side of a piece of paper for each power, so they’re both on the same page.) Your ideas could be general uses, specific uses, or examples of how the power could be used. • You might want to brainstorm uses for a power that nobody has chosen on the board, using the class’s ideas as a group. PHASE TWO: ORGANIZING A CONCEPT WEB • Using the concept web graphic organizer, students will organize their best (i.e., most persuasive) ideas from their brainstorms onto two concept webs. • Discuss the difference between a general use, a specific use, and an example. • Use your brainstormed uses that the class contributed above to develop general and specific uses, and then flesh out with examples on a concept web. The overhead projector might come in handy here. (I did it on the board.) PHASE THREE: CREATING AN OUTLINE Introduction to Outlining • Ask about students’ prior experience with outlines. Some have written them in Kate’s unit, and others have studied them in elementary school. Discuss how an outline is like a skeleton or an armature to build a well-organized essay or other writing piece around. • Students will need to make a final choice about which superpower to pick. Since they’ve written complete concept webs for both, they should have a good idea about which power has more convincing reasons. • Review/explain how Roman numerals work (especially I-XX). Roman numerals are used for the first (highest) level of information on an outline: the general topics. Transitioning from Concept Web to Outline: Labeling the Concept Web with Numbers and Letters • Using the sample superpower, written on a concept web and displayed on the overhead, decide and label each general idea with Roman numerals. Ask the students to think about which idea should appear first in the essay, which second, and so on. Then rearrange the “general use” numerals to reflect the class’s choices, or have students come up to the overhead and do this. • Next, label all of the specific topics/uses (2nd level branches from the general uses) with capital letters (A, B, C…) in the order the class thinks would make the most sense, for each branch around the concept web. • Then, label the examples and detailed ideas (3rd level) with numbers 1, 2, 3… Some Technicalities of Outlining: F.Y.I. • For students who ask about 4th level labeling, use lower case letters set off by parentheses: a), b), c)… The 5th level is labeled with numbers set off by parentheses: 1), 2), 3)… The 6th level is lower case Roman numerals: i), ii), iii)… and after that, the last three repeat with double parentheses, e.g.: (1), (2), (3), etc. • Typically, in an outline, you should not write a lower level under a heading if you only have one sub-topic to write. Lower levels should have at least two lines (e.g.: A. and B.). Information under a heading without another sub-topic under that heading should be included with that heading, not written as another level below it. However, because students may add more ideas as they go, I let them write only one sub-topic under a topic, as I don’t think it interferes with their writing. Writing an Outline • Tell the students that the title of their outline should be the name of their superpower. • Now, write the beginning of an outline for the students, modeling the organization that the students decided on with the concept web you worked with earlier. Refer to the sample outline: Talking With Trees Outline. • General topics (uses) will begin with Roman numerals next to the left margin. • Show how each progressive level gets indented a little more, so the letter or numeral is actually placed right under the first letter of the letter of the sentence above it. *Use the sample outline: Talking With Trees Outline. • Also, point-out that the entire entry on each sub-topic stays intented; the next line does not begin at the margin, but remains indented with the line above it. *Use the Poorly Indented Outline to show the difference. • Encourage students to change the organization before they begin their outline, or while writing it. This is the place to fuss over your paper’s organization: especially the order that you will present your ideas. • Also encourage students to add any new ideas to their outline that they didn’t have in their concept web before. Naturally, new ideas may come up: especially examples or details. Even a new general topic could come to mind. The outline is a great place to continue to add ideas while organizing how the essay will be structured. • Outlines take time. Allow students a couple of days in class and at home to perfect their outline. • To exceed expectations, some students may want to write a counter-argument or contrast their power to other super-powers, and include this in their outline. I recommend teaching the “WRITING AN ESPECIALLY PERSUASIVE ESSAY” section, below. PHASE FOUR: WRITING THE ROUGH DRAFT Writing an Introductory “Intro” Paragraph • Although It’s possible to include your intro paragraph in your outline, we don’t in this project. Instead, we’ll use the outline to help us structure an into paragraph for the beginning of our rough draft. • A thesis statement is the one (sometimes two) sentence, almost always in an essay’s intro paragraph, that “states” exactly what the entire essay is about. In a persuasive essay, the thesis statement will state what the essayist is trying to prove or convince her reader. Thesis statements are concise, and to the point. It’s this statement that “sums up” the whole essay in one sentence. It’s the seed of the rest of the essay. • A good into paragraph often consists of four parts: 1) A grabber or lead-in that invites or excites the reader to read on. (One to around five sentences.) 2) Transitional sentences that provide background, context, or important information to help you reader understand the thesis statement. (Usually not more than four or five sentences, if needed.) 3) The thesis statement. (Try to write it in one sentence.) 4) Sentences that clarify the thesis statement, describe how something might work, and/or link it directly to the various topics in the essay. (Usually one to five sentences, if needed.) The Lesson: Identifying Elements of an Intro Paragraph • Students will identify the four parts of an intro paragraph. • Give each table group of students the first pages of four super-power essays written by last year’s students. • With a partner, students will underline or circle grabber or lead-in sentences with green, transitional or context sentences blue, and the thesis statement of each essay with a red marker or pencil. • After each essay, each pair of students should double-check its work with the other two students at the table to make sure they all understand the idea and are doing it well. • Assess the students’ understanding as you move from table to table, and determine if and where students get stuck or confused. • Review on the overhead with one or two essays, if necessary. Writing an Intro Paragraph: Grabbers and Lead-ins • Discuss good ideas for grabbers. Questions, hypothetical situations, or invitations (that don’t sound like T.V. adds) all have potential to work well. But lead-ins don’t have to be exciting; they could also be sincere or poetic, and evoke the reader’s imagination, such as: For thousands of years, humans have lived with trees, and trees appear in the myths of cultures all around the world. Perhaps trees give us more than food and air to breathe. They certainly can live longer than people do. Perhaps they know things we haven’t yet understood. If a person could talk to trees, they could, perhaps, learn many amazing things. • Generate a grabber or lead-in that would invite or excite a high school student to read your essay. Share the grabber or lead-in with people at your table, and ask for constructive feedback. Get an honest opinion about your grabber. • Give a working title to your essay’s rough draft, indent five spaces, and write a lead-in or grabber or lead-in that you think will work well with your essay. Writing an Intro Paragraph: Determine Your Thesis Statement • Because the point of this essay is to argue why your super-power is the most useful, your thesis statement should reflect that. • Some thesis statements sound stronger or bolder than others, and, accordingly, become more difficult to argue or support. Compare these four thesis statements. Which is the strongest? Does it seem overly bold? Which is the least bold? Does it seem too weak? Talking to trees could be a useful super-power for someone to possess. The supernatural ability to talk to trees would help not just you, but other people as well. The ability to talk with trees is the most useful super-power that any human could have. Without a doubt, the supernatural power to talk with trees is the most useful power in the universe. • Facilitate a discussion to help the students see that the last statement will need many more ideas, examples, counter-arguments, and proof than the first statement—which seems easy enough to argue that many people might not even want to read on! • Students write the transition sentences to their thesis statement and their thesis statement. Finishing the Intro Paragraph • Tell the students that the final sentences in the intro paragraph help the reader see the general argument in your essay as an overview, or help the reader picture how something will work. • Some students may want to summarize their general uses for their power after their thesis statement. Compare these two approaches to writing an overview with the sample outline’s general uses: Or: If you could talk with trees, you could learn about things that trees can see, help many people eat, and enrich your life all around. If I could talk to trees, I would learn about things that trees can see as well as provide food to the hungry with my knowledge of their fruits. I could also have fun talking to trees. • This is a good place to describe how an unusual or difficult to imagine super-power works. Show, through images, exactly what happens to activate and use the power. For example: Someone with the power to consume pollution would generate a supernatural hunger for garbage spontaneously, whenever they felt angry about any type of pollution. After the hunger begins, any garbage would be licked up and devoured, and air pollution would be inhaled and processed through their lungs. Write the Body of the Essay • Now that their intro paragraphs are written, students can easily write their rough drafts by converting their outline into sentences. • Emphasize that all drafts must be double-spaced, to help edit the writing. Transition Words and Phrases • Introduce transition words and phrases to help the sentences “flow” together more easily, and to move from one idea to the next. Many excellent transition words and phrases from The Golden Page are listed on my website. Google search for “Craig” and “Mythology”; I’m the first on Google’s list: http://www.salmonbay.seattleschools.org/class/craig.html Writing an Essay’s Body Paragraphs • As a rule, each main idea or topic—in this essay, “general use”—will have its own body paragraph to support it. • A body paragraph typically has four parts: 1) A transition from the topic above to the new topic—if not done at the end of the last paragraph (a phrase or a complete sentence); 2) One topic sentence for that paragraph; 3) Two to ten supporting statements for that topic sentence, including details, arguments, and examples; 4) An optional transition to the next topic. • Note that a paragraph’s topic sentence may appear at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of a the paragraph. WRITING AN ESPECIALLY PERSUASIVE ESSAY Contrast Your Power with Other Powers • Your essay will be especially persuasive if you can write of good reasons that your power is more useful than other specific, popular super-powers, such as: flying, weather control, time-travel, or healing. One of your final paragraphs may wish to include that counter-argument. Write a Counter Argument • Another option for building an especially powerful argument is to defend the weaknesses of your super-power by writing a counter-argument. Think of the reasons why many would think your power was not the most useful; then, write to convince that person that either: 1) 2) 3) 4) The flaw is not very serious, problematic, or major, or The flaw is a misunderstanding of the power, or The weakness can be compensated or solved somehow, or Even with that failing or flaw, your choice of power might still prove to be the most useful because of other uses that most people may not have thought about. Then you’ll have to bring those uses to light! You may use more than one of the above counter-arguments. WRITING A CONCLUSION • Students may either write a concluding statement as a paragraph or as a sentence or two at the end of their last boy paragraph. Generally, this choice hinges around the length and complexity of their essay. Ending a Short Essay • If the essay is less than two pages, a simple restatement of the thesis—writing the same meaning in a different way—will do the trick and conclude the essay well. • If the essay is longer than two pages, and especially if many different ideas, examples, and counter-arguments have been written, a concluding paragraph is appropriate. Ending a Longer Essay: Writing a Concluding Paragraph • A concluding paragraph typically has four parts: 1) A transition from the body of the essay to the conclusion (one sentence); 2) A restatement of the thesis (a new way to write the thesis statement in one or two sentences); 3) A summary of the essay’s main topics—in this essay, general uses (one to four sentences); 4) A closing statement, which reconnects the reader back to his/her life, leads them to think about larger issues, or ends with a poetic image or final thought (one to three sentences).