Philo and the Epistle to the Hebrews

advertisement

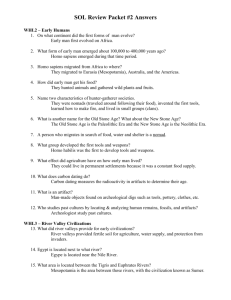

Philo and the Epistle to the Hebrews: Ronald Williamson’s Study after Thirty Years1 KENNETH L. SCHENCK 1. 2. 3. 4. Introduction The Fundamental Differences 2.1 Eschatology 2.2 Allegory 2.3 The Extent of the Differences 2.3.1 The Cosmology/Psychology of Hebrews 2.3.2 Philo’s Eschatology 2.3.3 The Exegetical Methods of Hebrews and Philo Hebrews, Philo, and Alexandrian Judaism 3.1 Fundamental Similarities 3.2 Hebrews and Middle Platonism 3.2.1 The Intermediary Realm 3.2.2 The Heavenly Tabernacle Conclusion 1. Introduction Susanne Lehne, in a 1990 monograph on the new covenant theme in the Epistle to the Hebrews, made a passing comment that reflects in more than one way the status quaestionis in regard to the relationship of Hebrews to Philo. In a casual footnote she wrote, ‘There can be no denying the presence of Platonic thought patterns in Heb, which may have reached our author through the Middle-Platonism current in his day.’2 What is ironic is that Lincoln Hurst’s monograph of the same year concluded on the same issue that ‘The Platonic/Philonic background for Hebrews is … ‘not proven’, and as such…must give way to an examination of other possible backgrounds.’3 These two quite different statements reflect the somewhat ambiguous state of the question in Hebrews scholarship today. On the one hand, Hurst stands in a tradition that goes back to C. K. Barrett’s foundational 1956 article, ‘The Eschatology of the Epistle to 1 This article is an edited version of a paper presented to the SBL Philo of Alexandria Group at the 2000 annual meeting in Nashville, Tennessee. 2 The New Covenant in Hebrews, JSNTSS 44 (Sheffield 1990) 129 n. 26. 3 The Epistle to the Hebrews: Its Background of Thought, SNTSMS 65 (Cambridge 1990) 42. For Hurst, ‘not proven’ means ‘not so’. the Hebrews’, an important benchmark on the question of Hebrews’ background.4 In that article Barrett argued that the thought of Hebrews was much closer to apocalyptic Jewish traditions than to Philo, even if the author might have used Platonic language in his argument.5 In the years that followed, the Platonic interpretation of Hebrews seemed to unravel in English scholarship, most noticeably in Ronald Williamson’s 580 page tome, Philo and the Epistle to the Hebrews, the focus of this article.6 In his often tedious investigation, Williamson systematically deconstructed the similarly compendious study of Çeslas Spicq, whose 1952 two volume commentary on Hebrews had been a tour de force some twenty years before.7 Spicq had contended on a grand scale that the author of Hebrews was ‘un philonien converti au christianisme’. Nevertheless, Williamson’s study showed that the particular arguments Spicq had used were often tendentious and careless. It would be easy for some to see Hurst’s subsequent monograph as the ‘nail in the coffin’ of the Philonic interpretation, effectively bringing to conclusion a consensus that had lasted for over half a century.8 Yet despite the dissimilarities between Hebrews and Philo, a significant number of scholars—perhaps in fact the majority—still believe there to be some relationship between the two, even if it is only a distant one.9 Indeed, at the time his book was published Williamson himself could write that the author was ‘a thinker undoubtedly 4 In W. D. Davies and D. Daube (edd.), The Background of the New Testament and Its Eschatology, Festschrift for C. H. Dodd (Cambridge 1956) 363-393. 5 ‘Eschatology’ 389, 393. 6 ALGHJ 4 (Leiden 1970). 7 L’Épître aux Hébreux, vol. 1 (Paris 1952) 91. 8 Others who believe that Hebrews has more affinities with apocalyptic traditions than with Philonic ones include Barrett, ‘Eschatology’ 393; G. B. Caird, ‘The Exegetical Method of the Epistle to the Hebrews’ CJT 5 (1959) 45; G. Hughes, Hebrews and Hermeneutics: The Epistle to the Hebrews as a New Testament Example of Biblical Interpretation, SNTSMS 36 (Cambridge 1979) 63; Hurst, Background 38-42; and D. A. deSilva, Perseverance in Gratitude: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on the Epistle “to the Hebrews” (Grand Rapids 2000) 27-32; to name only a few. 9 A number of other backgrounds have of course been suggested as the interpretive key to Hebrews. See Hurst’s monograph. Platonism and ‘apocalyptic’ remain the major contenders. 2 influenced by Alexandrian literature and by the Book of Wisdom in particular’. 10 In another place Williamson quotes with approval Spicq’s contention that Philo and the author of Hebrews both came from ‘une source alexandrine commune’.11 In the end, it was the idea that Hebrews had been directly or indirectly influenced by Philo himself that Williamson vigorously opposed, not the claim that they came from similar cultural backgrounds. On this broader level of consideration, a moderate consensus on the question of Philo and Hebrews does not seem too far out of reach. In fact, it is fairly close at hand—even if the right hand sometimes does not seem to know what the left is doing. The moderating position that places Hebrews and Philo in the same general stream of Hellenistic, perhaps even Alexandrian Judaism commands a great deal of support. Harold Attridge writes, ‘there are undeniable parallels that suggest that Philo and our author are indebted to similar traditions of Greek-speaking and –thinking Judaism.’12 David Runia similarly concludes ‘the author of the Hebrews and Philo come from the same milieu in a closer sense than was discovered in the case of Paul. I would not be at all surprised if he had had some form of direct contact with Judaism as it had developed in Philo’s Alexandria.’13 But perhaps Helmut Feld put it best when he noted that while the extensive discussion has not been able to prove that the author specifically knew Philo’s works, it has not disproved he knew Philo’s thought either. What is relatively certain, Feld claims, is that the author ‘in den exegetischen Methoden des hellenistischen Judentums gebildet war, und mit einer gewissen Wahrscheinlichkeit, daß er diese Bildung in Alexandrien erhalten hat.’14 10 Philo 406. I say ‘at the time’ because Williamson later made a case for Merkabah mysticism as the principal background against which to read Hebrews (cf. ‘The Background of the Epistle to the Hebrews’, ExpTim 87 [1976] 232-37). 11 Philo 571. 12 The Epistle to the Hebrews (Philadelphia 1989) 29. 13 Philo in Early Christian Literature: A Survey (Minneapolis 1993) 78. 14 ‘Der Hebräerbrief: Literarishe Form, religionsgeschichtlicher Hintergrund, theologische Fragen’, in ANRW II 25.4 (1987) 3550. 3 If this much is probable, and we believe it is, then a whole set of interpretive options suddenly moves from the realm of the possible to the probable. Indeed, it is interesting that even though Williamson himself accepted that the author had come under Alexandrian influence, he was so preoccupied with the desire to distance Hebrews from Philo that he often went to the opposite extreme. Thirty years later, with a better understanding of both Hebrews and Philo, it seems possible to reach a more balanced conclusion. At the very least, the writings of Philo and other Alexandrian Jews provide us with the most helpful non-biblical corpus for understanding the cosmology and metaphysic of Hebrews.15 While the author’s thought is fundamentally eschatological in orientation, his cosmology and metaphysical language broadly coheres with Middle Platonic thought. The way he16 quotes certain Scriptures may even point to the Alexandrian synagogues as his point of origin. Nevertheless, at crucial points the author does not argue from biblical texts in quite the way we would expect him to argue if he were promulgating a straightforward Philonic message. Thus while Hebrews and Philo both seem to draw on similar Alexandrian traditions, they develop them quite differently. 2. The Fundamental Differences 2.1 Eschatology The last thirty years have significantly tempered a number of Williamson’s claims and arguments, many of which were overstated and/or anachronistic. Nevertheless, his discussion of ‘Time, History, and Eschatology’ points to the most significant difference between the thought of Hebrews and Philo.17 While the thinking of Hebrews is thoroughly and fundamentally eschatological in orientation, Philo’s thought was not.18 15 So also S. Sowers, The Hermeneutics of Hebrews and Philo (Richmond 1965) 66. 16 I use the masculine pronoun for the author advisedly in the light of the masculine singular participle of Heb 11:32. 17 ‘[T]he fundamental difference between the thought of Philo and that of the Epistle to the Hebrews is shown in their deeply differing attitudes to time’ (Philo 144-45). However, many of Williamson’s arguments are now dated, such as his neat distinction between ‘cyclical’ Greek thought and ‘linear’ 4 Hebrews’ entire argument is premised on the idea that Christ’s death has taken place at the ‘consummation of the ages’ (Heb 9:26), that his audience is in the ‘last days’ (1:2) before the messiah returns a second time (9:28), and that the created realm will soon be removed by the fiery judgment of God (12:25-29). Faith in Hebrews is primarily forward looking toward future objects of hope. The ‘things not seen’ of which faith is the substance are things to come (11:1), and the ultimate rest we are striving to enter relates to a heavenly city at which we have not yet literally arrived (4:11; 11:16; 13:14).19 The author even situates his contrast between Christ and the angels within an eschatological framework, for the angels were ministers of the old covenant to those ‘about to inherit salvation’ (Heb 1:14).20 On the other hand, Christ has recently been exalted above the angels to the right hand of God, enthroned as royal Son, Christ, and Lord (1:4, 5-6, 8-9, 10). Now that he is crowned with glory and honor, he will lead many other sons to a glory greater than the angels (2:10) as long as his brothers endure to the end in faithfulness (3:6; 6:11; 10:25-39). The framework of Hebrews’ thought is the Christian thinking (Philo 148). M. Hengel’s Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in their Encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period (Minneapolis 1974 [1966]) rightly called into question stereotypical dividing lines between Greek and Jewish thinking, while the work of G. B. Caird and N. T. Wright has called into question whether all early Christians were expecting the end of the world (e.g. Caird, New Testament Theology, Lincoln Hurst (ed.) [Oxford 1994] 250-67; Wright, The New Testament and the People of God [Minneapolis 1992] 332-34). 18 L. K. K. Dey would be a rare example of someone who would still accentuate the vertical dimension of Hebrews almost to the exclusion of any horizontal (cf. The Intermediary World and Patterns of Perfection in Philo and Hebrews, SBLDS 25 [Missoula 1975]). For Barrett, ‘the eschatological is the determining element’ (‘Eschatology’ 366). For Hurst, ‘Barrett has done irreparable damage to the view that Auctor allows a Platonic-type dualism to control his thinking. Barrett, with Williamson, has established the role of history and time in the epistle’ (Hebrews 11). 19 Cf. Williamson, ‘The “things not seen” referred to as the objects of faith are events, miraculous events, the mighty acts of God performed in response to man’s trust in Him, not the world of incorporeal essences or the intellectual wisdom to comprehend that invisible dimension of reality’ (Philo 359). It is of course possible that in Middle Platonic thought the two categories might not turn out to be mutually exclusive. 20 See my article, ‘The Celebration of the Enthroned Son: The Catena of Heb 1:5-14’, JBL 120 (2001) 469- 85. 5 narrative of salvation history, a plot that is fundamentally horizontal and teleological in orientation. In contrast, Philo’s orientation was overwhelmingly vertical. The scarcity of messianism in Philo is well known, even if sometimes overstated.21 The focus of Philo’s writings was not on the attainment of Israel’s national destiny or on a return to some primordial cosmic order. Rather, he concentrated on the problem of virtue in the context of a dualism of body and mind. His concern was how the human mind could transcend sense perception and the passions associated with our bodies in order to reach heavenward to truth, virtue, and God (e.g. Opif. 151-170; Leg. 1.53-55, 88-89, 90-96). Philo vigorously rejected the Stoic idea of eventual world conflagration (e.g. Aet. 7576), and any notion of resurrection is entirely absent from his writings. Rather he speaks of the soul’s immortality (Ios. 264). For Philo, faith primarily involved a trust in the incorporeal, conceptual world (Praem. 26) over and against ‘the bodily and the things outside the soul’ (Abr. 269).22 Faith is ‘always to see the one who is’; it is heavenward in orientation, something to enjoy throughout one’s whole life (Praem. 27). In short, the dominating framework of Philo’s thought is vertical rather than horizontal. We can at least agree with Hurst, Williamson, and Barrett that the orientations of Hebrews and Philo are different, even if they might share some other features in common. 2.2 Allegory Philo’s writings display a penchant for allegorical interpretation that the book of Hebrews does not clearly reflect. For Williamson, ‘the almost complete absence from Hebrews of that method of scriptural exegesis which was all-important to Philo must mean that the 21 Some scholars have argued that Philo had no real ‘linear’ element in his thought at all—even in De Praemiis, the most eschatologically oriented of all Philo’s treatises (cf. B. L. Mack, ‘Wisdom and Apocalyptic in Philo’, SPhA 3 [1991] 21-39). Cf. Williamson, ‘There is in Philo no eschatology’ (Philo 556) and ‘There is no appreciable Messianism in Philo’s works’ (530), although he recognizes the eschatological element in De Praemiis (143-44). 22 All translations are mine. 6 Writer of the Epistle can hardly have once been a Philonist.’23 Williamson is not the first to point out differences between the ways Philo and Hebrews use Scripture. Many of the comparative studies of Williamson’s day emphasized this distinction.24 Hebrews resorts to typology, so the typical analysis went, while Philo interprets allegorically.25 Williamson connected Hebrews’ typological exegesis with its eschatological orientation, while he related Philo’s penchant for allegory to his more ‘philosophical’ interests.26 Underlying his observations seems to be the implication that typology is more respectful of a text’s historical, literal meaning while allegory is more ‘disrespectful’, unconcerned with its original sense. While he acknowledged that Philo could interpret a text literally, Williamson largely saw Philo’s fondness for allegory as a way of dodging the literal meaning when it was inconvenient.27 While we should question the underlying value judgments of Williamson’s argument, Philo does utilize allegorical exegesis far more commonly in his corpus than the author of Hebrews does in his short sermon. And Williamson was correct to connect typology with the eschatological orientation of Hebrews. A narrative stood at the very heart of early Christian thought, a fact that lent itself naturally to typology. In typological exegesis, parallels are drawn between earlier and later elements in a story. Thus 1 Peter 3:21 considers the waters of the Flood, an event from the narrative past, to be a type of baptism, an element of current experience (‘Peter’ seeing himself as a character in the same story). The interpreter sheds light on a later aspect of the story by comparing it 23 24 Philo 533. E.g. R. P. C. Hanson, Allegory and Event: A Study of the Sources and Significance of Origen’s Interpretation of Scripture (London 1959) 83-86. Even some who argued for a strong connection between Hebrews and Philo acknowledged this distinction (e.g. Spicq, Hébreux 2.183; Sowers, Hermeneutics 137). 25 Williamson (Philo 530) quotes Sowers: ‘typological exegesis is totally absent from Philo’s writings’ (Sowers, Hermeneutics 91). 26 E.g. Williamson, Philo 529-36. 27 Cf. Philo 523-29. At one point Williamson even lightheartedly uses the word perverse in reference to some of Philo’s allegories (Philo 529). He did not inveigh against Philo’s character in general, but Williamson did imply throughout his discussion that Philo’s use of allegory made his interpretations inferior to those of Hebrews. 7 with an earlier event, person, or entity. In this respect, Hebrews’ entire rhetorical agenda is typological, for the author pits the entirety of Christ’s work against the old covenant and Levitical cultus. On the other hand, Philo was concerned with timeless philosophical truths. He was not relating Scripture to particular events or experiences of recent history. Rather he was concerned to illuminate the nature of virtue and how to attain it. As such, allegorical rather than typological exegesis lent itself more readily to his aims and goals. Interestingly, as Hebrews made various points of the story into types of Christ and his work, Philo used various aspects of the story to draw allegorical inferences about the soul. By far the most common allegory from which Philo builds his interpretations is his ‘allegory of the soul’. If Hebrews saw Christ everywhere in the Jewish Scriptures, Philo saw the soul and its struggle for virtue everywhere in the Pentateuch. Thomas Tobin’s analysis of the creation of man in Philo’s writings has highlighted the way Philo developed certain philosophical traditions he himself inherited. 28 One interesting by-product of this study is the realization that it is exactly at the points where Philo himself is developing such traditions that he looks least like the Epistle to the Hebrews. We will suggest subsequently that Hebrews shows greater similarity to some of the philosophical traditions Philo inherited than it does to Philo’s own distinctive ideas. Philo’s principal contribution to the creation tradition was his allegory of the soul. While previous interpretations believed Genesis to refer to two different men in the external world, Philo internalizes the story in terms of two different kinds of mind a person might have. In particular, the figures of Adam, Eve, and the serpent in Genesis 23 come to represent the mind (Adam) that struggles with pleasure (the serpent) and the deceptiveness of sense perception (Eve).29 28 Philo’s allegorical writings abound with The Creation of Man: Philo and the History of Interpretation, CBQMS 14 (Washington D.C. 1983). I speak of ‘philosophical traditions’ here in a very broad sense. We can of course debate at what point such traditions should be deemed ‘Middle Platonic’. 29 Creation 32-35, 135-176. 8 imagery of this sort.30 Well beyond his discussion of the creation of humanity, Philo’s treatises return time and time again to the conflict within the soul between the mind, passions, and sense perception. Clearly the text of Hebrews does not share Philo’s preoccupation with allegory or his focus on achieving virtue by overcoming passions and sense perception. Hebrews formulates its sense of human imprisonment and conflict almost entirely in terms of sin and death (e.g. Heb 2:15; 7:23, 27-28) rather than in terms of conflict within the soul.31 The solution of humanity’s problem is achieved through cleansing (e.g. 10:2), through which human perfection comes (e.g. 7:19; 10:1-2).32 Liberation for Hebrews is not so much a matter of this life—it is not the successful resolution of an inner tension while one is still on earth. Salvation for an individual human is heavily future in orientation as it looks to Christ’s return and the eventual removal of the created realm (e.g. 1:14; 9:28; 12:26-27). Such salvation comes on the basis of an eschatological event in the story whose literal occurrence is essential to its effectiveness. To the extent that Hebrews alludes to the creation and ‘fall’ of humanity, it does so on literal terms (cf. 2:6-8). Interestingly, in the one instance where Hebrews quotes a text from the creation story, its interpretation is diametrically the opposite of Philo’s.33 From these observations it is clear that Philo and Hebrews differ significantly from one another in their main interests and emphases. Hebrews shows no clear trace of Philo’s most signature idea, the allegory of the soul, and Philo would have rejected the 30 E.g. Opif. 154-57; Leg. 2.19-25; Det. 15-17; Agr. 130-33; Plant. 36-39; Conf. 191-98; Som. 2.246-49; just to touch the surface. 31 Space does not permit a comparison of Hebrews and Philo on the subject of sacrifice. Even Williamson concludes that ‘it cannot be denied that there are some similarities in what Philo and Hebrews say on this subject’ (Philo 182). 32 Dey’s attempt to interpret Hebrews by way of Philo’s understanding of perfection provides us with a quintessential example of allowing a background corpus to ‘take over’ the text you are actually trying to interpret (Patterns). We learn a great deal about Philo from Dey’s work but almost nothing about Hebrews. 33 Namely, Hebrews’ interpretation of Gen 2:2 in Heb 4:4. For Hebrews, God not only rested from his works on the seventh day. He has rested ever since (4:3). For Philo, however, God caused rest on the seventh day—it is conceivable that God himself would rest (Leg. 1.6; cf. Williamson, Philo 541). 9 particular eschatology of Hebrews out of hand. We must reject the interpretations of those who find in Hebrews an awkward attempt to fit a Christian eschatology into a Platonic framework.34 Hebrews is thoroughly and fundamentally a document of early Christianity. While the author’s thought and argument may have Middle Platonic elements, he has not allowed them to distract from his basic eschatological schema in any way. 2.3 The Extent of the Differences 2.3.1 The Cosmology/Psychology of Hebrews The basic differences between Hebrews and Philo are not difficult to identify. A more important question, however, is whether their thought contradicts in a substantial way. Williamson began his study with a sense that scholars had exaggerated the influence of Philo on Hebrews’ thought. As such he set out to show that Hebrews was not dependent on Philo’s works.35 Given the state of the question at that time, Williamson successfully made his case. Spicq’s commentary had overstated the connections between Hebrews and Philo on a massive scale. Similarly, while Philo and Hebrews are sometimes similar, we can point to no clear instance where Hebrews is literarily dependent on Philo’s writings.36 Nevertheless, Williamson also exaggerated the differences between Hebrews and Philo at many points. The fact that Hebrews’ thought is fundamentally eschatological in 34 E.g. E. F. Scott, The Epistle to the Hebrews: Its Doctrine and Significance (Edinburgh 1922) 109, 115; J. Moffatt, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews (Edinburgh 1924) xxxii, xxxiv, liv; J. Héring, ‘Eschatologie biblique et idéal platonicien’, In W. D. Davies and D. Daube (edd.), The Background of the New Testament and Its Eschatology, Festschrift for C. H. Dodd (Cambridge 1954) 453. 35 Williamson, Philo 8-10, 492-3. Cf. J. W. Thompson, The Beginnings of Christian Philosophy: The Epistle to the Hebrews, CBQMS 13 (Washington D.C. 1982) 8-10. 36 Although the number of superficial parallels is quite impressive. While no one instance is determinative, a cumulative case could be made that Hebrews and Philo must have shared a very similar thought environment. 10 orientation does not necessarily exclude the possibility that it also has a vertical, dualistic dimension resembling Middle Platonic metaphysics.37 On the one hand, the catastrophic nature of the coming judgment, the ‘shaking of the created realm’ (Heb 12:27), might at first seem more reminiscent of apocalyptic literature than of Philo’s thinking—for him the world is indestructible (Aet. 75-76).38 Yet the thought of Hebrews does have a cosmological and ‘psychological’ dualism underlying its argument that resembles Middle Platonic categories more than those of apocalyptic. For example, it would not contradict the eschatological framework of Hebrews if the heavenly realm were a place that, like Philo’s ether, was not made of any of the stoixei/a of the created realm (Leg. 3.161; Her. 281-83). Hebrews divides the universe into two categories—created things and unshakeable things (Heb 12:27). God will remove the created heavens on the Day of Judgment (12:26), but presumably the heaven where God is—higher than the created heavens (cf. 7:26)—will remain unshaken (cf. 9:24).39 The earthly tabernacle is a kosmiko/n sanctuary—one connected with the created realm—as opposed to the true, ‘heavenly’ one (9:1; cf. 8:1-2). Christ’s priesthood is effectual not least because he serves in heaven rather than on earth (8:4-5). 37 So U. Luz, ‘Der alte und der neue Bund bei Paulus und im Hebräerbrief’, EvT 27 (1967) 331-33; B. Klappert, Die Eschatologie des Hebräerbriefs (München 1969) 59; H. Braun, ‘Die Gewinnung der Gewissheit in dem Hebräerbrief’, TLZ 96 (1971) 327; G. W. MacRae (author Platonist, audience not), ‘Heavenly Temple and Eschatology in the Letter to the Hebrews’, Semeia 12 (1978) 179-99; G. Sterling (audience Platonic, author not), ‘Ontology versus Eschatology: Tensions between Author and Community’, in D. T. Runia and G. E. Sterling (edds.), In the Spirit of Faith: Studies in Philo and Early Christianity in Honor of David Hay, SPhA 13 (2001) 208-10. 38 However, apocalyptic writings more typically envisage the renewal of the creation rather than its removal: a ‘new heavens and a new earth’ (cf. Isa 65:17; 66:22; Jub. 1:29; Rom 8:19-22; 1 En. 45:1-5; Rev 21:1; 4 Ezra 6:15-16; 7:75). We should note that the early Stoics expected a world conflagration (cf. 2 Pet 3:10), although the Middle Stoa largely rejected this idea. 39 The word meta/qesij can mean either ‘removal’ or ‘transformation’ (Heb 12:27). Nevertheless, the context of Heb 12:27 points to removal rather than transformation. The context divides reality into two mutually exclusive categories—shakeable/created and unshakeable. Only the unshakeable remains after God’s cataclysmic judgment. 11 Because Middle Platonism combined elements of Stoic materialism with Platonism,40 it became possible for events to take place in the realm of intermediate realities.41 Indeed, Philo’s picture of angels as priests in a heavenly temple may imply some sort of rational, bloodless oblation that takes place in the heavens (cf. Spec. 1.66; cf. T. Levi 3:5). Hebrews’ distinction between body and spirit is also reminiscent of traditions found in the Philonic corpus. On the one hand, we should not confuse Plato’s body-soul dichotomy with the Cartesian dualism of material/immaterial.42 We would more accurately distinguish between corporeal/incorporeal, assuming that all heavenly realities are made of ‘stuff’ of one density or another.43 Philo thus passes on a Stoic interpretation of Gen 2:7 in which the spirit God breathes into Adam is a fragment of the divine (e.g. Leg. 1.39-40).44 Similarly, in Gig. 60 Philo speaks of the human mind as the heavenly component in us.45 In Hebrews, God prepares a body for Jesus on earth (Heb 10:5, 10), but Christ offers himself to God through ‘eternal spirit’ in heaven (9:14).46 The blood of bulls and goats 40 Cf. G. J. Reydams-Schils, Demiurge and Providence: Stoic and Platonist Readings of Plato’s ‘Timaeus’, Monothéismes et et Philosophie (Turnhout 1999); Tobin, Creation 18. 41 Thus even Hurst admits that Philo could have conceived of God pitching an ‘archetypal’ tent (Background 29). Cf. however Opif. 17. 42 Cf. D. Martin, The Corinthian Body (New Haven 1995) 3-15. 43 Cf. J. Dillon, ‘Asômatos: Nuances of Incorporeality in Philo’, in C. Lévy (ed.), Philon d’Alexandrie et le langage de la philosophie, Monothéismes et Philosophie (Turnhout 1998) 99-110. 44 Cf. Tobin, Creation 21. 45 Philo’s understanding of the soul is generally tripartite, sometimes involving the mind (nou=j, the rational part of the soul; cf. Leg. 1.39), sense perception (ai1sqhsij), and the passions (ta\ pa/qh, these two form the irrational parts to the soul; cf. Leg. 2.6). Cf. also Her. 55, where Philo calls the human spirit the ‘soul of the soul’. Philo can also speak of the soul in terms of 1) reason, 2) high spirit and 3) appetite (Leg. 1.70; 3.115), and in another instance he speaks of a seven-part soul (Opif. 117). 46 Most translations interpret ‘holy spirit’ in Heb 9:14 as a reference to the Holy Spirit. An allusion to the Holy Spirit is not impossible, but pneu+ma is anarthrous, highlighting the character of the offering— spiritual—rather than the Holy Spirit as the specific spirit in question. Even more than the blood of Christ, it is the spiritual and thus heavenly nature of the offering that really contrasts with the earthly, fleshly blood of bulls and goats. 12 might clean flesh, but Christ’s heavenly offering cleanses conscience (9:13-14). Angels in Hebrews are ministering spirits (1:7, 14), and Hebrews speaks of the human spirit as the part of us that pertains to the heavenly Jerusalem (12:23). God is the father of our spirits (12:9),47 but Christ’s time on earth was the ‘days of his flesh’ (5:7) when he partook of ‘blood and flesh’ (Heb 2:14). We might even read the author’s sole reference to Christ’s resurrection more as a passage upward from the realm of the dead rather than a corporeal reconstitution of some sort (13:20).48 Along with Hebrews’ clearly drawn distinction between body and spirit is a latent emphasis on the rational. The author encourages the audience to exercise their senses (Heb 5:14; ai0sqhth/rion), a Stoic technical term found a number of times in Philo.49 Throughout Hebrews 9 and 10 he contrasts flesh with conscience (9:9, 14; 10:2, 22), where conscience is understood as a faculty of memory.50 Indeed, we can best explain the need of the heavenly tabernacle for cleansing in Heb 9:23 by supposing that at this point of the argument the author is basically thinking of Christ’s offering in the tabernacle as a metaphor for the cleansing of the conscience—that rational/spiritual element of a human being that potentially pertains to the heavenly realm.51 Perhaps it is 47 While this comment is an allusion to Num 16:22, Hebrews’ use of the phrase places it within its overall body/spirit dualism. 48 Heb 13:20 uses a0na/gw, which can mean ‘brought up’ as well as ‘brought again’. However, Heb 6:2 uses traditional Christian corporeal language: ‘resurrection of dead [=corpses]’. 49 Philo himself uses the word eight times: Leg. 1.104; 3.183, 235; Det. 15; Post. 112; Ebr. 155, 201; Conf. 20. In my opinion, Williamson’s attempt to distinguish between an emphasis on the organs of sense in Philo and a more metaphorical reference to the senses in Hebrews is not only questionable but also makes a distinction without a difference (Philo 114-16). Heb 5:14 reminds us of 4 Macc 2:22, where the mind is enthroned above the senses. Interestingly, Williamson claimed that Hebrews has a significant overlap in vocabulary (22 words that are hapax legomena in Hebrews) with 1-4 Maccabees (Philo 14-15). 50 Note the parallelism between sunei/dhsij and a0na/mnhsij in Heb 10:2-3. An ‘evil conscience’ in 10:22, therefore, probably refers to an awareness of unatoned sins. 51 Cf. W. R. G. Loader, Sohn und Hohepriester: Eine traditionsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zur Christologie des Hebräerbreifes, WMANT 53 (Neukirchen 1981) 169-70. 13 no mistake that Hebrews seems to distinguish between ‘sins committed in ignorance’ (e.g. 9:7) and sins committed ‘willfully’ (10:26). Hebrews thus draws clear lines between the human spirit/conscience and the body/flesh in the same way it draws distinctions between the created and the heavenly realms. The associations are more obvious and consistent than any apocalyptic writing. Rather, they bear a closer resemblance to the cosmology and psychology of the book of Wisdom (e.g. Wis 9:15) and Philo (e.g. Gig. 12, 31). On the other hand, there is nothing specifically Philonic about Hebrews’ use of this distinction. The similarities point more to a common milieu than to specific dependence. 2.3.2 Philo’s Eschatology Philo had an eschatology. While it did not play a major role in most of his writings, 52 De Praemiis indicates that Philo shared the common Jewish expectation that God would one day bring the Jews back to Jerusalem from the Diaspora (e.g. Praem. 165). At some point in the indefinite future they would enjoy incredible prosperity as well as victory over their enemies (Praem. 168-69). Philo even indicates that a messianic figure might become involved in bringing about this event, the ‘man’ of Num 24:7 (LXX).53 52 T. Tobin remarks, ‘had De Praemiis not been preserved, no one would have imagined Philo had written such a treatise’ (‘Philo and the Sibyl’, in D. T. Runia and G. E. Sterling [edds.], Wisdom and Logos: Studies in Jewish Thought in Honor of David Winston, SPhA 9 [1997] 94). 53 Praem. 95. Mack has noted that Philo does not interpret Num 24:7 messianically in Mos. 1.263-299 (‘Wisdom and Apocalyptic’ 34). He concludes that Philo does not really understand it to refer to a specific messianic individual but that it is rather a symbolic reference to Israel at its best. P. Borgen, on the other hand, argues from minor alterations Philo makes to the Numbers text that Philo did indeed expect a messiah to arrive as part of a literal restoration of Israel in the future (‘“There Shall Come Forth a Man”: Reflections on Messianic Ideas in Philo’, in The Messiah: Developments in Earliest Judaism and Christianity [Minneapolis 1992] 341-361). T. Tobin’s treatment of De Praemiis combines the strengths of both hypotheses by supposing that Philo saw two possible scenario’s leading to Israel’s restoration: 1) a preferred scenario in which the nations recognized the virtue of Israel without war and 2) a second option involving a messianic leader akin to that of Sibylline Oracles 3 and 5 (‘Philo and the Sibyl’ 100). 14 To be sure, Philo’s discussion lacks the combative, anti-Roman sentiments of a Psalms of Solomon 17 or Sibylline Oracles 3—he hopes that the virtue of Israel will move the world to acknowledge its superiority without war (Praem. 93). Yet his hopes for Israel are not merely allegorical or symbolic. They are literal, national, and very thisworldly in orientation. Clearly he saw no contradiction between such a future oriented hope and his overall philosophical agenda. Indeed, he was able to weave his allegory of the soul into this eschatological discussion (e.g. Praem. 158-61)! While Williamson thus observed correctly the difference between Hebrews and Philo in terms of their eschatological orientations, he was incorrect in the degree to which he insinuated they contradicted one another. 2.3.3 The Exegetical Methods of Hebrews and Philo One significant area in which Williamson’s treatment of Hebrews and Philo was seriously deficient was his discussion of their respective exegetical techniques. While it is true that Philo favored allegory and Hebrews’ exegesis was more typological, those of Williamson’s generation had latent biases that overemphasized the implications of this difference. In particular, we must seriously question the negative appraisal of allegory that dominated so much of twentieth century scholarship, along with the disproportionate favor shown to typology as a superior exegetical technique. On the one hand, Philo does not rely exclusively on allegorical method in his interpretation of the Pentateuch. Indeed, unlike many of his contemporaries, Philo could interpret a text on both a literal and an allegorical level. 54 Thus while his distinctive contribution at Alexandria was his allegory of the soul, Philo still believed in literal angels (e.g. Gig. 6-8), a literal heaven to which the souls of the virtuous would go at death (e.g. Abr. 258), and he believed that the characters of the Old Testament had been real people at one time. Further, he used allegory to varying degrees in his writings. Allegory understandably saturates the collection of treatises known as the Allegorical 54 Cf. Tobin, Creation 154-55 and D. M. Hay (ed.), Both Literal and Allegorical: Studies in Philo of Alexandria’s Questions and Answers on Genesis and Exodus, BJS 232 (Atlanta 1991) 29-46. 15 Commentary,55 but his Exposition of the Law is much more topical and literal in approach, even if we also find allegory from time to time.56 In short, the tendency to stereotype Philo as a particular kind of interpreter strictly because he favored allegorical interpretation relates to some of the same biases that in part led Adolf Jülicher to reject the historicity of any parable with more than one point. 57 I personally would suggest that the modern preoccupation with historicity and with reading texts in context has significantly colored this discussion in the past. Williamson viewed Philo’s allegorization in part as escapism from the literal meaning when it did not suit his purposes.58 In contrast, Williamson thought that ‘the typological exegesis of the Writer of the Epistle to the Hebrews is free from the strong tendency to arbitrariness of the purely allegorical method of interpretation.’59 Despite Williamson’s plaudits, however, typological exegesis is just as ‘pre-modern’ as allegorical interpretation, if not more so. We should not think that the author of Hebrews was any more historically conscious or sensitive than Philo was.60 Typological exegesis is not truly oriented around past history but around the past of the narrative from which it draws.61 A clearer understanding of Hebrews’ pre-modern hermeneutic helps resolve a number of interpretive controversies surrounding this early Christian homily. 55 E.g. Legum Allegoriae, De Gigantibus and De Somniis. 56 E.g. De Abrahamo, De Iosepho, and De Praemiis et Poenis. 57 Die Gleichnisreden Jesu, vol. 1 (Freiburg 1899) 169-73. 58 Philo 524-29. 59 Philo 532. 60 Thus Williamson: ‘The recognition of an event, person or institution as a “type” implies the acceptance of the historicity of that event, person or institution’ (Philo 530). The irony of pre-modern interpretation, however, is that it largely cannot distinguish between story and history—it is largely unaware of the potential distinction (cf. H. W. Frei, The Eclipse of Biblical Narrative [New Haven 1974] 2). 61 Contra Williamson (Philo 529-30), Hanson (Allegory 7), and even Sowers (Hermeneutics 89). 16 One such controversy is the significance of Melchizedek in Hebrews 7.62 In the first two verses of this chapter the author shows us clearly that he is not averse to using allegory to interpret Scripture—he provides us with a straightforwardly allegorical interpretation of Gen 14:17-20 (cf. Philo, Leg. 1.79). Indeed, the extremely controversial Heb 7:3 is basically a pastiche of allegorical conclusions compressed into one verse without the intervening interpretations.63 In the end, the controversy surrounding the interpretation of Melchizedek in this chapter has largely resulted from the desire to see some sort of literal figure behind the argument. Yet the author does not build his argument on the basis of the literal, ‘historical’ Melchizedek. Rather, Hebrews 7 is an interpretation of the phrase ‘a priest after the order of Melchizedek’ in Ps 110:4 by way of the story in Genesis 14. It was largely the allegorical significance the author of Hebrews could ascribe to various components in the Genesis story that he found valuable. Indeed, in the author’s interpretation not even the historical Melchizedek himself was a ‘priest after the order of Melchizedek’—only Christ fulfills such a role.64 Several elements in Hebrews’ interpretation of the two-part tabernacle in Heb 9:1-10 are also allegorical in orientation.65 For example, Gregory Sterling believes that the author’s cryptic comment in Heb 9:5 refers to a fuller allegorical interpretation he could have made with regard to the furniture of the earthly tabernacle.66 The parabolh/ of 62 For a survey of the various interpretations of Hebrews 7, see B. Demerest, A History of Interpretation of Hebrews 7,1-10 from the Reformation to the Present, BGBE 19 (Tübingen 1976) and F. Horton, The Melchizedek Tradition: A Critical Examination of the Sources to the Fifth Century A.D. and in the Epistle to the Hebrews, SNTSMS 30 (Cambridge 1976). 63 It is interesting that the word a0mh/twr often occurs in allegorical contexts in the Philonic corpus (e.g. Ebr. 61; QGen. 4.68). Williamson argues against dependence of Hebrews on Philo in such instances (Philo 20-23), but the general similarity is clear enough. 64 See my forthcoming book, The Thought World of Hebrews (Louisville 2003). 65 Contra Williamson, who denies any allegorical significance to the author’s use of parabolh/ in Heb 9:9 (Philo 533 n. 3). 66 ‘Ontology versus Eschatology’ 197. 17 Heb 9:6-10 is straightforwardly allegorical. The outer room of the tabernacle becomes an allegory for the current age and perhaps also the earthly realm, while the inner chamber comes to symbolize the age to come and perhaps the highest heaven. It would be easy to see in such symbolism an allegory for the eventual removal of the created realm (especially in 9:8; cf. 12:27). At the end of the day, it is unclear that the allegory/typology distinction contributes anything at all to the question at hand. Williamson could be correct in thinking that the author of Hebrews would have used more allegory if he had studied under Philo, but it is difficult to say. In the end, it is more the absence of the allegory of the soul that distinguishes Hebrews from Philo rather than the use of allegory in general. 3. Hebrews, Philo, and Alexandrian Judaism 3.1 Fundamental Similarities At the time he wrote, Williamson accepted that the author of Hebrews had come under the influence of Alexandrian traditions.67 Certainly the view that both Hebrews and Philo are products of Diaspora, Hellenistic Judaism commands a great deal of support among scholars, as would be the claim that both enjoyed the privilege of a Greek education. Beyond these fairly uncontroversial claims, it is not unlikely that both had significant connections to the Egyptian city of Alexandria. First of all, it seems almost certain that the author of Hebrews was a Greek-speaking Jew who did not know Hebrew or Aramaic. He gives every evidence that the Septuagint was his Bible.68 On more than one occasion he makes arguments that only work in the 67 Philo 406. 68 Williamson noted that of some 157 hapax legomena in Hebrews, 123 also occur in the LXX (Philo 15). Further, Hebrews holds 75 of its hapax legomena in common with Philo, while Hebrews and Philo only share 14 words that do not also appear in the LXX. At the conclusion of his analysis, Williamson ascented to the suggestion that ‘Philo and the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews were both using a common Alexandrian Jewish stock of vocabulary’ (Philo 11-18. Cf. R. P. C. Hanson, Allegory 94). 18 Greek language69 or that rely on unique features of the LXX translation.70 In and of itself, this observation eliminates some of the more fanciful reconstructions of Hebrews’ provenance, such as those requiring a direct connection of Hebrews with Qumran or Samaritan Judaism.71 Secondly, it seems likely that the author was one of the few elite to enjoy a Greek education. Not only is his Greek some of the best in the New Testament, but Hebrews displays great rhetorical awareness and skill.72 Walter Übelacker has even attempted to analyze Hebrews as a formal piece of deliberative rhetoric.73 All these factors point to a fair amount of Hellenistic education, perhaps even beyond the basic e0gku/klioj paidei/a (geometry, arithmetic, music, astronomy) to the study of rhetoric. Indeed, the author’s familiarity with the e0gku/klioj paidei/a leads him to use a common educational metaphor to insinuate that the audience is still on a beginner’s level with regard to their understanding of Christian truth. Although they should be teachers by now, he says, they still need instruction in the basic stoixei/a of beginning Christianity (Heb 5:12). They need milk rather than the strong meat the author has to offer. They are a1peiroj with regard to the word of righteousness, nh/pioi 69 E.g. the argument of Heb 9:16 only works because the Greek word diaqh/kh can mean both ‘covenant’ and ‘will’. 70 E.g. only the LXX text of Ps 40:6 reads ‘a body you prepared for me’. The Hebrew read ‘my ears you have opened’. All in all, Richard Longenecker notes 14 instances where the wording of biblical citations in Hebrews agrees with the LXX over and against the Masoretic text (Heb 1:10-12; 3:7-11; 3:15; 4:3, 4, 5, 7; 8:8-12; 10:5-7, 16, 17, 37-38; 12:5-6; 12:26; in Biblical Exegesis in the Apostolic Period [Grand Rapids 1975] 164-69). 71 See Hurst’s discussion of these suggestions, Background 43-66; 75-82. 72 In just the opening four verses alone, deSilva (Perseverance 37) catalogs such rhetorical devices as alliteration (Heb 1:1-3), homoeoptaton (1:3), hyperbaton, and brachylogy (1:4). The anaphora of Hebrews 11 is well known, and Attridge has further noted such devices as assonance, asyndeton, chiasm, hendiadys, and paronomasia (Hebrews 20-21). 73 Der Hebräerbrief als Appel: Untersuchungen zu exordium, narratio, und postscriptum (Hebr 1-2 und 13,22-25), ConBNT 21 (Stockholm 1989). Such a designation does not preclude the significant epideictic portions of Hebrews argument (cf. deSilva, Perseverance 46-58; and Attridge, Hebrews 16 n. 135). 19 (5:13). On the other hand, strong nourishment is for those who are te/leioi, those who through exercise (e3cij) have trained their senses (ai0sqhth/ria) to discern the difference between good and bad (5:14). The metaphors of these verses show up widely in popular philosophical writings of the time in regard to various levels of education. For example, Philo can use the word stoixei=on to refer to a letter of the alphabet such as one would learn when one was a beginner (Congr. 149-50). In a very striking passage (Agr. 9), he refers to those in the early stages of Hellenistic education (propaideu/mata) as nh/pioi who are on milk. Later in the same book he notes that such individuals are a1peiroj (Agr. 160). On the other hand, the te/leioi are those who are equipped to learn about prudence, temperance, and virtue (Agr. 9). Of course Philo is not the only person to use such imagery in ancient literature. The similarities point more to a common milieu rather than to a literary dependence of Hebrews on Philo.74 Yet even in the case of Williamson, the evidence led him to concede that ‘the Writer of Hebrews drew upon the same wealth of literary vocabulary and moved in the same circles of educated thought as men like Philo.’75 Perhaps the greatest argument for a substantial connection between Hebrews and Alexandria in particular comes from a number of variant forms of the LXX text that Hebrews and Philo uniquely quote in the same way. David Runia has recently pointed to four passages that Hebrews and Philo cite in the same way. For example, they both render Gen 2:2 as kai\ kate/pausen o9 qeo\j e0n th|= h9me/ra| th|= e9bdo/mh a0po\ pa/ntwn tw=n e1rgwn au0tou= even though no known form of the LXX has the words o9 qeo\j e0n.76 Further, they both include the word pa/nta in their discussion of Exod 25:40, transposing the occurrence of this 74 Thompson thus seems to overstate his case with regard to this parallel between Hebrews and Philo (Beginnings 17-40). 75 Philo 296. 76 E.g. Heb 4:4 and Post. 64. 20 word in Exod 25:9.77 Both apply Prov 3:11-12 in terms of God admonishing his children.78 These are significant similarities. However, the most noteworthy similarity between Hebrews and Philo is the way they both cite a composite text made up of Josh 1:5, Deut 31:8, and possibly Gen 28:15. Remarkably, this conflated text appears in exactly the same form in both Philo and Hebrews: ou0 mh/ se a0nw= ou0d 0 ou0 mh\ se e0gkatali/pw.79 It is difficult to know exactly to what extent we should take such a striking similarity as a sign of common origins. Even for Williamson, this commonality implied a geographical proximity for both writers, namely, Alexandria.80 For David Runia as well, the use of these four texts in Hebrews ‘is so close to Philo that coincidence must be ruled out.’81 Here is probably the most striking evidence for a connection between the author of Hebrews and Alexandria. We might easily suppose that these variant forms represent the text of the LXX in use in the synagogues of Alexandria and that the author of Hebrews, like Philo, learned this wording there. 3.2 Hebrews and Middle Platonism 3.2.1 The Intermediary Realm One of the characteristic features of Middle Platonism is the existence of a transcendent One (the ultimate archetype)—the ground of all existence.82 Philo predictably associated this ultimate cause with God. But if God was singular, then the Middle Platonists needed some sort of intermediate domain with an infinite number of more specific archetypes, 77 Heb 8:5 and Leg. 3.102 (Philo unsurprisingly uses para/deigma from Ex. 25:9 instead of tu/poj). 78 Heb 12:5 and Cong. 177. 79 Heb 13:5 and Conf. 166. 80 Philo 571; so also Spicq, Hébreux 1.336 and Sowers, Hermeneutics 66. 81 Philo in Early Christian Literature: A Survey, CRINT 3 (Minneapolis 1993) 76. Sowers claimed additionally that the Old Testament citations of Hebrews frequently follow the text of Codex Alexandrinus, adding further evidence for a connection between Hebrews and Alexandria (Hermeneutics 66). 82 Cf. J. Dillon, The Middle Platonists (Ithaca 1996 [1977]) 128; Tobin, Creation 14. 21 the more direct causes of the things we experience in the earthly realm.83 In Philo this approach sometimes led to a three-tiered view of reality: 1) God, the ultimate pattern, 2) the intermediary realm, which both a) is a copy/image/shadow of God and yet b) also provides the patterns for the sense-perceptible world, and 3) the physical, corporeal, sense-perceptible world around us, which consists of the copies/images/shadows of the patterns in the intermediary realm. Given that Stoicism stands in the background of some aspects of Middle Platonic thought, it is not surprising that the notion of logos came to play a role in this schema. For Philo, the logos in general is the copy/image/shadow of God (e.g. Leg. 3.96). It was through the logos that God created the world. In turn, the logos itself is the pattern after which entities in the sense-perceptible world are copied. This basic system of thought was not unique to Philo—he was drawing on various Alexandrian traditions he inherited from his own environment.84 In my opinion, it is virtually certain that some early Christian individual, a person influenced by this fairly uniquely Alexandrian synthesis of ideas, came to have a significant, perhaps even immense influence on the development of early Christology. We can see him (her?) in the background of the Colossian hymn 85 and in the Johannine prolog, perhaps also in 1 Cor 8:686 and even the Philippian hymn.87 Perhaps it was the author of Hebrews. 83 So Dillon, Middle Platonists 128; Tobin, Creation 15. 84 Perhaps the majority of Philo scholars point to Eudorus of Alexandria in the mid-first century BCE for the ‘moment’ of Middle Platonism’s birth (e.g. Dillon, Middle Platonists 114-129; Tobin, Creation 13-15). Apparently Jews before Philo had seen the possibility of applying Eudorus’ ideas to the LXX. 85 Cf. Sterling, ‘A Philosophy according to the Elements of the Cosmos: Colossian Christianity and Philo of Alexandria’, in C. Lévy (ed.), Philon d’Alexandrie et le langage de la philosophie, Monothéismes et Philosophie (Turnhout 1998) 349-73. 86 Cf. Sterling, ‘‘Wisdom Among the Perfect’: Creation Traditions in Alexandrian Judaism and Corinthian Christianity’, NovT 37 (1995) 355-84. 87 I do not necessarily mean that such an individual or individuals actually composed all of these hymnic pieces. It only seems likely to me that at some point someone introduced Alexandrian categories into the 22 Hebrews reflects this dimension of Alexandrian thought in a number of ways. For example, Philo’s comments on angels provide us with some of the closest parallels to Hebrews’ discussion of them in Hebrews 1.88 As in Philo, angels in Hebrews are nonembodied spirits who serve as ministers and messengers to the earthly realm. Nevertheless, there is nothing uniquely ‘Philonian’ about Hebrews treatment of angels. More significant are those points at which Hebrews parallels Middle Platonic language and thought relating to the logos. For example, the exordium of Hebrews states that Christ is the one di’ ou[ God made the worlds, that he is the a0pau/gasma of God’s glory and the xarakth\r of his u9po/stasij (Heb 1:3). All these comments are reminiscent of things said in Alexandrian literature about either the logos or personified wisdom. The statement that Christ was the one di’ ou[ the worlds were made is strikingly similar to Philo’s comment in Spec. 1.81 that the logos is the ei0kw/n of God di’ ou[ the whole world was constructed. Similarly Wis 9:1 says that God made the universe by his logos. In fact, Heb 1:3 is likely an allusion to Wis 7:26, which states that wisdom is an ‘a0pau/gasma of eternal light … an ei0kw/n of God’s goodness’. Given the similar parallelism in the two verses and the fact that this is the only occurrence of a0pau/gasma in the LXX, it seems almost certain that Heb 1:3 implicitly compares Christ to God’s wisdom. While a0pau/gasma is at least a hapax legomena in the LXX, the word xarakth/r does not occur at all. Yet both appear a number of times in the Philonic corpus, where Philo uses such terms to steer Stoic materialism in a more Platonic mix of early Christian thought—categories that moved Christology significantly down the kinds of paths that eventually led to the catholic creeds of the church. 88 Some relevant passages include Virt. 74; Somn. 1.141-43; Conf. 174; Decal. 46; Mos. 1.66; 166; Plant. 14. 23 direction.89 Whereas the Stoics believed that the human spirit was a fragment of ethereal fire, the Middle Platonists used Aristotle’s notion of a fifth substance distinct from fire, namely ether, to disassociate the human soul from any of the four basic elements of the physical world. Hebrews does not use these terms in exactly the way Philo did. We should probably take Heb 1:3 metaphorically. Christ is God’s wisdom for the creation, and he reflects the brightness of God’s glory. This statement refers to the fact that Christ has been crowned with the glory and honor God intended for humanity to have from the beginning (Heb 2:9). To that glory Christ will also lead many sons (2:10). The ‘character’ of that ‘substance’—a substance that can indeed be connected on one level with holy spirit (6:4; cf. 3:14; 11:1)—is reflected perfectly in Christ (cf. Somn. 1.188). I have argued elsewhere that Hebrews does not literally consider Christ to be the agent of creation but rather uses images traditionally associated with wisdom to imply that Christ embodies God’s purposes for the creation.90 Therefore, when Hebrews says that Christ is the one di’ ou[ the worlds were created, it is saying that Christ is the embodiment of God’s creative wisdom. Similarly, the phrase fe/rwn ta\ pa/nta tw=| r9h/mati th=j duna/mewj au0tou= is probably another comparison of Christ to God’s creative wisdom (cf. Her. 36; Mut. 256). While we might debate the exact nuances of these words and phrases, it is fairly clear that they find their closest parallels in Alexandrian Jewish literature. Even Williamson agreed that ‘the Writer was familiar with and was drawing upon the language used about Wisdom in the Alexandrian work ‘The Wisdom of Solomon.’’91 Surely Heb 4:12-13 stands in the same vein as Wis 18:15-16, where God’s all powerful logos leaped from heaven with the sharp sword of God’s command in judgment of the Egyptians. Thus 89 Tobin, Creation, 85-93. For this reason J. Frankowski argues strongly that Heb 1:3 is dependent on Philo’s thought (‘Early Christian Hymns Recorded in the New Testament: A Reconsideration of the Question in the Light of Heb 1,3’, BZ 27 [1983] 183-94). 90 ‘Keeping His Appointment: Creation and Enthronement in the Epistle to the Hebrews’, JSNT 66 (1997) 91-117. 91 Philo 410. 24 Williamson was surely too quick to disassociate Hebrews from the ‘cutting logos’ (lo/goj tomeu/j) of Philo (e.g. Her. 130-32).92 While we cannot prove that the author of Hebrews was dependent on Philo, we can plausibly assert that all three writers were passing on common Alexandrian traditions at these points. It is perhaps important to note that Hebrews does not explicitly equate Christ with the logos, as the Gospel of John does. Indeed, God speaks through Christ in Hebrews (e.g. Heb 1:2); Christ is not what he speaks. We should rather think of the logos in Hebrews as God’s directive word for his people and his creation. His word accomplishes what it sets out to do (Isa 55:11). God speaks many times in Hebrews, whether it be words of salvation (2:2-4) or words of judgment (4:12-13). Hebrews is thus parallel to Philo, but its use of such imagery takes place on a much more elementary level.93 A final place where the imagery of Hebrews sounds reminiscent of Philo’s logos schema is in the argument of Hebrews 8-10, where terms like skia/ (Heb 8:5; 10:1) and ei0kw/n (10:1) occur. We will discuss this imagery in more detail in the following section. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the language of skia/-ei0kw/n- pra/gma that appears in Heb 10:1 is reminiscent of the three-tier view of reality we have just mentioned. Heb 9:11 states that Christ arrived as a high priest of good things that have come about. On the other hand, Heb 10:1 states that the Law only had a skia/ of coming good things. Further, this shadow was not itself the ei0kw/n of those realities (pragma/ta). It would be difficult to fit these comments into a straightforward Middle Platonic scheme, but the language is Middle Platonic. The Law entailed a shadow of the reality of true cleansing, but it did not present a straightforward image of that cleansing— 92 Philo 391-95. 93 Cf. D. Runia’s comment that Hebrews ‘presupposes a Logos theology which is somewhat less developed than Philo’s, closer to what we find in the Wisdom of Solomon’ (Christian Literature 76). Sterling also claims that Hebrews ‘does not reflect a profound understanding of Platonism; it only betrays a knowledge of Platonizing exegetical traditions’ (‘Ontology versus Eschatology’ 210). 25 it was not that exact a representation. The language certainly sounds like what we find in places like Leg. 3.95-96 in Philo’s works, but it is difficult to make a precise comparison. We can at least conclude from these parallels that Hebrews has come under Alexandrian influence in the way it uses logos and wisdom imagery. Of course such imagery may not have been localized in Alexandria. While we cannot prove dependence on Philo’s writings, we can point with confidence to a common milieu. 3.2.2 The Heavenly Tabernacle The verse in Hebrews that by far lends itself most naturally to a Platonic interpretation is Heb 8:5: They [earthly Levitical priests] ‘by a shadowy u9podei/gmati serve the heavenly [holies], just as Moses has been warned as he is about to complete the tent, for ‘Look,’ he says, ‘you will make everything according to the type that was shown to you on the mountain’ (Exod 29:40)’ The majority of New Testament translations, as well as the majority of Hebrews scholars, have regularly translated the phrase u9podei/gmati kai\ skia|~ as ‘by copy and shadow’. As with 10:1 and the verses preceding 8:5, these words have a vaguely Platonic feel to them. When we realize that Philo and the book of Wisdom also used Exodus 29 in reference to the ideal tabernacle, a connection with Platonic thought seems even more likely.94 On the other hand, Lincoln Hurst has cast serious doubt on the translation of u9po/deigma in Heb 8:5 as ‘copy’, claiming that the word never has this meaning in all of the extant Greek literature at our disposal.95 While Hurst may have overstated his case, he is at least correct that Philo would much more likely have used para/deigma 94 Cf. Philo, Leg. 3.102 and Wis 9:8. 95 Background 13. Attridge suggests a few instances where he thinks it does (Hebrews 219), namely, the LXX of Ezek. 42:15 and Aquila’s rendering of Ezek. 8:10 and Dan. 4:17. Sterling also argues for this basic sense in Her. 256 (‘Ontology versus Eschatology’ 195). 26 at this point than u9po/deigma.96 The NRSV translation committee, convinced by Hurst’s arguments, has more recently rendered the word as ‘sketch’. We get even more curious when we note that the author of Hebrews chose Exod 25:40 at this point rather than Exod 25:9. When Philo speaks of the archetypal pattern Moses saw, it is the para/deigma he sees, not the tu/poj (e.g. Leg. 3.102). It is hard to imagine why someone advocating a straightforward Platonic meaning would not use para/deigma from Exod 25:9 rather than the tu/poj of 25:40. It seems we must conclude either that the author is not thinking Platonically in the first place,97 is not fully competent in his Platonism,98 or is deliberately avoiding a straightforward Platonic connotation.99 I personally believe that we have in Heb 8:5 another instance where the author is thinking far more exegetically than ontologically. As in the case of Melchizedek, the author believes that there were literal priests who served in a physical tabernacle in the past. But he is primarily interested in the ‘types’ and ‘examples’ he can glean from the text of Exodus rather than in any literal priests or structures. In Philo, the terms u9po/deigma and tu/poj more often relate to interpretations of the biblical text rather than to Middle Platonist ontology.100 The framing of the biblical citation in Heb 8:5 points us in the same exegetical rather than ontological direction. Hebrews uses the perfect tense when it notes that Moses ‘has been warned’ about how to make the tabernacle. The use of the perfect tense relates the 96 Sterling suggests that the author might have had Ezek 42:15 in mind, leading him to use u9po/deigma instead of para/deigma (‘Ontology versus Eschatology’ 195). Ironically, this is the same connection Hurst uses to argue against a Platonic meaning (Background 15-16). 97 Hurst’s position (Background 13-17). 98 Sterling approximates this position (‘Ontology versus Eschatology’ 210). 99 One could spin MacRae’s position in this direction. He believed that the author was Platonic in orientation but his audience was more apocalyptic (‘Heavenly Temple’). One could argue that the author ‘veiled’ his full position in order to make his message more palatable to his audience. 100 Cf. Opif. 157, where Philo speaks of the text of Genesis providing dei/gmata tu/pwn—‘examples of types’, probably a genitive of apposition. 27 words of Exodus not so much to a historical event in the past when Moses saw a heavenly archetypal pattern but to a message about Christ that continues to stand in the text of Exodus up until the present. It is in this sense that the law ‘has’ a shadow of coming good things (Heb 10:1). It contained in its pages a ‘shadowy example’ of what was to come, although not an exact ‘image’ of that reality—Christ. The law was the witness of Moses to the ‘things going to be spoken’ in the days of Christ (3:5). What we find is that Philo still provides us with the best backdrop for understanding this verse, but it is Philo the exegete rather than Philo the philosopher. The seemingly contradictory images of the heavenly tabernacle in Hebrews 8-10 roughly fall into place when we realize that the author is relating a number of biblical texts in typological and allegorical ways to Christ’s recent ‘sacrifice’ and entrance into heaven. 101 Thus not only the Day of Atonement sacrifice is a type of Christ’s sacrifice (e.g. Heb 9:7), but the inauguration of the wilderness tabernacle (9:19), the red heifer ceremony (9:13), and the cleansing ritual involving hyssop (9:19) are also types of Christ as well.102 The heavenly Holy of Holies can also be a metaphor for heaven itself (Heb 9:24)— Hebrews gives us no clear reference to an outer room in the heavenly tent.103 Since Christ’s entrance into the heavenly sanctuary corresponds to his exaltation to the right hand of God, it is tempting to see the heavenly tabernacle in Hebrews after the model of the universe as God’s temple, a view that appears occasionally in Philo’s writings. 104 Yet 101 E.g. the author amalgamates the sacrifice of the Day of Atonement (Heb 9:7) and the inauguration of the wilderness tabernacle (9:19) with various rituals for the cleansing of uncleanness (9:13, 19). All the different sacrifices of the Levitical cultus become shadowy examples of Christ’s singular sacrifice. 102 Cf. N. H. Young, ‘The Gospel According to Hebrews 9’, NTS 27 (1981) 198-210. 103 After all, the conclusion of Hebrews is that Christians have unhindered access to God now (e.g. Heb 4:14-16). How could there be a veil now in the heavenly sanctuary (cf. Rev 21:22)? 104 E.g. Somn. 1.215; Spec. 1.66; Mos. 2.88; QEx. 2.91. Yet Josephus also knows this tradition, showing that the view was widely held (cf. Ant. 3.123; 3.180-87). 28 Hebrews is more complex still than even this model, for Heb 9:23 almost equates the human conscience with this heavenly ‘space’.105 From this discussion we find once again that a number of traditions in Philo potentially shed light on Hebrews’ argument. Yet Hebrews always bears the closest similarity to the traditions on which Philo himself is drawing rather than on his own unique contributions. The evidence points to a quite similar background, yet not clearly to any kind of direct dependence or influence. 4. Conclusion At the end of reexamining Williamson’s work, we can affirm a number of things with confidence. First of all, the author of Hebrews and Philo had much in common. Both were Greek speaking Jews of the Diaspora who had enjoyed the privilege of the e0gku/klioj paidei/a. Both were reliant on the LXX and used similar textual traditions, perhaps even some particular to the synagogues of Alexandria. Both were heirs of various elements from the philosophical traditions we usually associate with Alexandrian Judaism. We can say with great certainty that the author of Hebrews knew of the Wisdom of Solomon. Further, we cannot rule out the possibility that the author was aware of Philo’s writings. I personally would not be at all surprised if he had had some general acquaintance with them. Yet the author is thoroughly and fundamentally Christian; whatever pre-Christian views he might have had, the matrix of an eschatologically oriented Christianity has transformed them. Williamson did a good job of showing that the author of Hebrews was first and foremost a Christian whose thought often differed significantly from Philo. Yet Williamson also overstated his case in many instances. Thirty years after Williamson dethroned Spicq we can continue to affirm the conclusion of Sidney Sowers: ‘Philo’s 105 For a discussion of the heavenly tabernacle in Hebrews, see my Ph.D. dissertation, ‘The Settings of the Sacrifice: Eschatology and Cosmology in the Epistle to the Hebrews’, University of Durham (1996) 14292. 29 writings still offer us the best single body of religionsgeschichtlich material we have for this N.T. document.’106 106 Hermeneutics 66. 30