China`s Growth Model

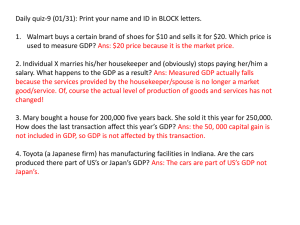

advertisement