dehydratation_press_release

advertisement

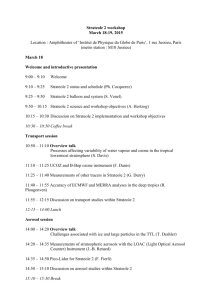

DEHYDRATION IN HEALTHY ADOLESCENTS AFFECTS BRAIN STRUCTURE & FUNCTION Equating to same level of shrinkage expected in Alzheimers’ Patients over two and a half month period Research paper published in Human Brain Mapping* reporting medical study of 16-18 year olds, identifies that whilst dehydration may not immediately appear to affect brain function in the short-term, for teenagers taking GCSE’s or A-Levels over consecutive days, performance could be significantly affected Leading wellbeing and hydration expert, Water for Work and Home, has recently sponsored a medical study at King’s College London on the dehydration affects on brain structure and function in healthy adolescents. The results of the study, designed and carried out by Neurosense, in collaboration with the Newcomen Group of scientists and business professionals, have identified that hydration needs to be a major issue for adolescents, their parents and, crucially, their schools. This could be particularly important in the run up to and during the GCSE and A-Level exams. In particular the study identified that significant negative effects of dehydration with structural changes in the brain equated to the same level of shrinkage expected in Alzheimers’ patients over a two and half month period, or 14 months of ageing in otherwise healthy individuals. It has been observed that dehydration causes shrinkage of brain tissue and an associated increase in ventricular volume. Negative effects of dehydration on cognitive performance have been shown in some but not all studies, and it has also been reported that an increased perceived effort may be required following dehydration. However, the effects of dehydration on brain function are unknown. But greater insight has now been provided in the study sponsored by Water for Work and Home, which has been published in Human Brain Mapping*. This was led by Matthew J Kempton and Marcus Smith and investigated the question using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in 10 healthy adolescents. Each subject completed a series of exercises which resulted in dehydration. They were then tested for their cognitive performance. The study found that dehydration following the exercises led to a marked increase in frontoparietal brain areas necessary to perform an executive function task (Tower of London) compared to a control condition. Cerebral perfusion during rest was not affected. The increase in response after dehydration was not paralleled by a change in cognitive performance, suggesting an inefficient use of brain metabolic activity following dehydration. This pattern indicates that dehydrated participants exerted a much higher level of neuronal activity in order to achieve the same performance level. Given the limited availability of brain metabolic resources, these findings suggest that prolonged states of reduced water intake may adversely impact executive functions such as planning and visuo-spatial processing. “Given that there isn’t always any immediately observable effect on function from dehydration, we are therefore particularly concerned about the possible longer term effects on individuals who aren’t sufficiently hydrated” explained Professor Gemma Calvert, Chair of Applied Neuroimaging, University of Warwick and a Co-Founder of NeuroSense. “Just because you can’t tell that someone is dehydrated from their behaviour that doesn’t mean their brain and body aren’t immune to the effects.” And this is precisely what the research confirmed. “The research identified that reaction times in the acutely dehydrated were no worse than those not dehydrated, when looking at immediate short-term effects”, continued Professor Calvert. “But, crucially, fMRI neuroimaging results showed significant negative effects of dehydration with structural changes in the brain that equated to the same level of shrinkage expected in Alzheimer’s patients over a two and half month period, or 14 months of ageing in otherwise healthy individuals. “In particular, an increase in neuronal activity required to perform a complex thinking task was detected in the acutely dehydrated, compared to the non-dehydrated, which suggests that the human brain compensates for dehydration by working harder. But given the frugal nature of brain function, it seems unlikely that such effort could be sustained and, as a result, there could be a decline in performance over the working day.” Ben McGannan, Managing Director of Water for Work and Home believes this study provides some important pointers for adolescents, their parents and their schools as we head into the schools exam season. “ We strongly believed that that dehydration was an issue in effecting students’ performance, but we sponsored this research to give us clear evidence. And it now appears that whilst students may be able to tackle one exam a day whilst dehydrated, if they have several exams to take on the same day, lack of regular access to drinking water could have a seriously detrimental affect on their results. “Clearly the simplest way to tackle this issue is to allow students to bring drinking water into exam halls as well as ensure that drinking water is easily accessible near exam halls. But we know that some schools are concerned about students’ need to visit the toilet and therefore aren’t quite as willing to encourage consumption of water through the school day. There’s also an issue of what students are allowed to take into exam halls. “But this new research sends alarm signals that long-term effects of dehydration amongst adolescents could be quite severe if not tackled quickly.” Water for Work and Home is a business that focuses on wellbeing, including hydration and its importance at and during work. In particular, the company has been addressing the issues of hydration in schools. It has been running a programme – ‘We Love Water’ specifically focused on pre-schools, primary and secondary schools to improve understanding and awareness of the importance of hydration in the school day. In one project alone, focusing on hydration in Pre-school groups in Kent, 73% of practitioners think the ‘We Love Water’ programme has been beneficial, encouraging children to drink more water and learn how to take responsibility for their own hydration. *Dehydration Affects Brain Structure and Function in Healthy Adolescents has been published in Human Brain Mapping, 2010. The full paper can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20999 The Pubmed link is http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20336685 END