china`s trade policies and its integration into the world economy

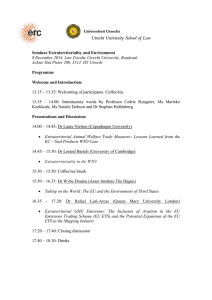

advertisement