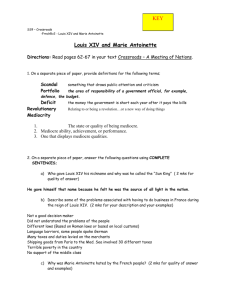

Marie Antoinette Final Paper

advertisement

Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of a Misunderstood Woman Melissa Ford History 299 March 25, 2009 2 From the moment she first arrived at the French Court in 1770 to marry the future French King, Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette was doomed to become one of the most criticized women of the eighteenth century. Originally an Archduchess of Austria, Marie Antoinette’s welcome to France consisted of scorn and ridicule that ultimately resulted in a contorted image of the then fifteen year old girl. Over time, and through lack of analysis by historians, the biased view of Marie Antoinette, placed upon her by the French elite, became ingrained in general thought. Thus, in order to prove Marie Antoinette’s generosity and kindness, the primary documents written about the Queen have to be placed back into the context from which they were written. This paper seeks to prove that because of their fear of foreigners, discrimination, and negative ideas of women in politics, the French Court and the Revolutionaries damaged Marie Antoinette’s image and reputation to the point that the citizens, as well as many future historians, and thus, future generations, came to share their opinion. Though the works produced about Marie Antoinette have consistently reiterated the belief that she behaved flippantly, recent trends show that historians, particularly female ones, believe that Marie Antoinette was grossly misinterpreted. Such male historians as Hilaire Belloc and Andre Castelot, in their respective biographies, Marie Antoinette (1924) and Queen of France: A Biography of Marie Antoinette (1957) continued a trend of refusing agency to Marie Antoinette, proclaiming instead that her selfishness and inability to control her own fate led to her ruin.1 As time progressed, Desmond Seward and Joan Haslip, in their biographies, Marie Antoinette (1981) and Marie Antoinette (1987) became the first historians to give her back her Hilaire Belloc, Marie Antoinette (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924), 527; Andre Castelot, Queen of France: A Biography of Marie Antoinette, trans. Denise Folliot (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957), ix. 1 3 agency and take a more personal approach in analyzing the Queen.2 In the last few years, historians have once again taken a different approach in viewing Marie Antoinette. No longer caring about her agency, Lynn Hunt, in her article “The Many Bodies of Marie Antoinette: Political Pornography and the Problem of the Feminine in the French Revolution,” (2006), looks at Marie Antoinette as a symbol which the Jacobin’s used to destroy any attempts of females to play a public and political role.3 Thus, in connecting Hunt’s theories to Seward’s and Haslip’s approach, Marie Antoinette’s misrepresentation is displayed. The displeasure and fear with which French citizens regarded Austria disadvantaged Marie Antoinette before she entered France. In 1763, the Seven Years’ War ended in humiliating defeat for France. The French resented Austria’s claim on resources sorely needed by France to defend its colonial empire.4 The disgust of the Austrians, brought about in part by the Seven Years’ War, eventually resulted in the hatred of the family that ruled it. Lavicomterie de SaintSamson, a Jacobin leader, declared, “If there was ever on earth a dynasty fatal to and destructive of the human race, it was without contradiction the infamous house of Austria.” The French citizens also bemoaned what they considered as “feminine” techniques in gaining superiority— that of corruption, gifts, and the marrying of daughters to foreign princes.5 Thus, in this atmosphere, Marie Antoinette, an Austrian princess of the Habsburg family, entered into union with the dauphin Louis-Auguste, a move meant to strengthen the Austrian-French alliance. Desmond Seward, Marie Antoinette (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981), 12-13; Joan Haslip, Marie Antoinette (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987), xi. 2 Lynn Hunt, “The Many Bodies of Marie Antoinette: Political Pornography and the Problem of the Feminine in the French Revolution,” in The French Revolution: Recent Debates and New Controversies, ed. Gary Kates (New York: Routledge, 2006), 204-205. 3 4 Thomas E. Kaiser, “From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot: Marie-Antoinette, Austrophobia, and the Terror,” French Historical Studies 26, no. 4 (Fall 2003): 585-586, http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.umw.edu :2048/journals/french_historical_studies/v026/26.4kaiser.pdf (accessed 3/31/09). 5 Kaiser, “From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot,” 590. 4 Almost immediately, Marie Antoinette found herself subject to suspicion and prejudice. Princess Lamballe, a favorite and intimate friend to the Queen, further expressed this hostility in her journal, Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, revealing, “All the interest by which this union was supported could not, however, subdue a prejudice against it, not only among many of the Court, the cabinet, and the nation, but in the Royal Family itself.”6 Alone in a foreign land, burdened with the hatred of the French Court simply because of her Austrian birth and receiving no support from the Royal Family, Marie Antoinette immersed herself in the familiar, bringing Austrian tastes to the court. Whereas previous French queens had attempted to hide their foreign backgrounds, Marie Antoinette openly expressed her origins, an action that did little to help her situation.7 Her failure to convert completely into a French noblewoman deepened the suspicions that surrounded her. Doubts of Marie Antoinette’s loyalty to France eventually culminated in the belief that she was trying to influence the King politically. Her enemies in the court claimed she directed foreign policy to advantage Austria, as well as exported funds from the country for the benefit of her brother, Joseph II. Around the time of the French Revolution, these treasonous ideals merged with new ones, mainly that she promoted civil disorder and supported a foreign invasion.8 Circulation of pamphlets by both the Brissotins and her court opponents, including the king’s aunts, Adelaide and Victoire, that encouraged these thoughts, eventually led to the mythical Austrian Committee.9 This fabricated committee, supposedly headed by Marie Antoinette and in 6 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, ed. Catherine Hyde (Washington: M. Walter Dunne, 1901), 18. 7 Kaiser, “From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot,” 586. 8 Kaiser, “From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot,” 587. 9 The Brissotins were a group of republican politicians in France. They were named after their outspoken leader Jacques Pierre Brissot. For more information on this political party see, Eloise Ellery, Brissot de Warville: A Study in the History of the French Revolution (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1915). 5 league with Vienna, was a counter-revolutionary faction that organized armed resistance to the national assembly.10 Initially used by the Brissotins as a case for war against Austria, Marie Antoinette’s inevitable connection created more difficulties for her, including her imprisonment. The fear attributed to her connection with the committee, including her plots to mobilize forces against France led to condemnation. One of many to viciously attack the Queen, the Popular and Republican Society of Cambrai (a Jacobin society), proclaimed at the time of Marie Antoinette’s incarceration, “So long as she exists, this Austrian viper, she will conspire from the bottom of her prison… So long as she exists, she will corrupt our generals… make us lose battles… [and] slaughter our brothers.”11 The Jacobins, not to be outdone, added their voice, asking, “How is it that the wife of the tyrant, or rather she who was herself our cruelest and fiercest tyrant, still pollutes the air of liberty with her impure breath?”12 Both of these sources reflect the view of Marie Antoinette at the time of the revolution, which the court and revolutionaries both tried to enforce. They conveyed the portrayal of her as a treasonous tyrant to the citizens of France, who quickly started attacking her also. However, accounts of those familiar with the Queen had a different picture of her loyalties. Louis-Philippe de Ségur, a Count and acquaintance of the King and Queen, believed that Marie Antoinette showed appropriate devotion to France, writing in his book, The Memoirs and Anecdotes of the Count de Ségur, “She spoke of the successes of our forces on land and sea and of the advantages of a glorious peace for France with the pride and sentiment of a queen, and Gary Savage, “Favier’s Heirs: The French Revolution and the Secret du Roi,” The Historical Journal 41, no. 1 (March 1998): 241, http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/stable/pdfplus/2640151.pdf (accessed 3/31/09). 10 11 Kaiser, “From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot,” 597-598. 12 Kaiser, “From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot,” 600. 6 of a French queen at that.”13 Though only mentioned once and briefly, Ségur’s account provides a differing opinion that did not view her as a foreign woman who cared nothing for France, an image revealing the Court’s accusations as false. Burdened by her birth alone, Marie Antoinette never stood a chance in earning the loyalty and respect of the French Court. In fact, the lack of support from the French Court damaged her reputation to the point that the citizens came to share the general opinion of the Queen as an unstoppable corrupting force. The fear that the Court held for her was not the only reason for the extreme dislike they expressed towards the Austrian princess. Marie Antoinette brought a wave of reform with her from Austria, a change that many, especially older nobles, greatly disliked. Recognizing the immediate prejudice against her, Marie Antoinette proceeded to structure the Court in such a way that she isolated herself from many of the more powerful families at Court, choosing to associate only with her circle of friends. This blatant favoritism meant that Marie Antoinette dispensed favors on her friends, leaving the rest of the court offended. Their hatred of the Queen became so great that they actually shunned Versailles.14 However, a possible explanation for the Queen’s reluctance to converse with the rest of the Court, despite their hostility, seems to stem from a lack in confidence. The Princess Lamballe wrote, “The education of the Dauphiness was circumscribed; though very free in her manners, she was very deficient in other respects; and hence it was she so much avoided all society of females who were better informed than herself.”15 Uncomfortable around women 13 Louis-Philippe de Ségur, The Memoirs and Anecdotes of the Count de Ségur, trans. Gerard Shelley (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1928), 152. 14 Daniel L. Wick, “The Court Nobility and the French Revolution: The Example of the Society of Thirty,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 13, no. 3 (Spring 1980): 268-271, http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/ stable/pdfplus/2737985.pdf (accessed 3/31/09). 15 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, 19-20. 7 scrupulous in their etiquette, and acknowledging the disastrous potential of showing weakness, Marie Antoinette chose to avoid the problem altogether. The loss of support from the nobles was one of the greatest dangers for the King and Queen because it relayed doubts to the citizens, making them more apt to believe the rumors they heard from the Court. The Court accused Marie Antoinette of frivolity and rudeness out of spite because they did not understand that their discrimination against the Queen produced the reason for her lack of friendliness towards them. Calling her “Madame Deficit”, Marie Antoinette’s enemies in the Court charged her with spending the entire nation’s money on her extravagant lifestyle.16 However, the Princess Lamballe revealed that all of the Queen’s expenses came from her own private purse and the three hundred thousand francs allowance given to her by Louis XVI, was a sum, the Princess pointed out, less than half what Louis XV had spent on his mistresses.17 The Court ignored this and instead distributed libelles (political pamphlets meant to disparage public figures) throughout the country.18 In Princess Lamballe’s own words, “Thus, in the heart of the Court itself, originated the most atrocious slander, long before it reached the nation, and so much assisted to destroy Her Majesty’s popularity with a people, who now adored her amiableness, her general kind-heartedness, and her unbound charity.”19 Though as a close friend and confidant of the Queen, Princess Lamballe classifies as having bias, another source also provides evidence of the Queen’s charity. Henriette-Lucy Dillion, a lady-in-waiting to the Queen, revealed in her Memoirs of Madame de La Tour du Pin, 16 Wick, “The Court Nobility and the French Revolution,” 272. 17 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, 59-60. 18 Wick, “The Court Nobility and the French Revolution,” 272. 19 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, 106. 8 that the Queen ritually would take up a collection from the nobility to give to the poor.20 The generosity described by both these ladies does not agree with the slanderous pamphlets that called the Queen selfish. However, the citizens only saw the negative leaflets distributed by the Court. Most of the animosity that the French Court felt for the Queen seemed to come from her ignorance of French customs. The Court of Versailles, according to the Princess Lamballe, enjoyed its strict traditions and rigorous etiquette.21 The expectation to uphold decorum was so strict that, a page at the court during Louis XVI’s reign, Felix D’Hezecques, comments in his memoir, Recollections of a Page at the Court of Louis XVI, “It was quite a study for any one who arrived at the Court, and had not been brought up there, to become perfect in the laws of etiquette.”22 Marie Antoinette, forced into such an environment with little experience and at the young age of fifteen, immediately found herself ridiculed for her mistakes. The Princess Lamballe revealed the Court lady’s resentment of Marie Antoinette’s “encroachments upon their habits.”23 D’Hezecques revealed how her occasional break in etiquette to obtain some innocent amusement “was magnified into a crime, and was the origin of all the calumnies that were disseminated about her.”24 Count de Ségur explained that weakening of etiquette under Marie Antoinette’s reign was a sign of national decadence.25 Dillion recalled an event in which the 20 Henriette-Lucy Dillion, Memoirs of Madame de La Tour du Pin, ed. and trans. Felice Harcourt (New York: The McCall Publishing Company, 1971), 75. 21 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, 30. Felix D’Hezecques, Recollections of a Page at the Court of Louis XVI, ed. Charlotte M. Yonge (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1873), 165. 22 23 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, 31. 24 D’Hezecques, Recollections of a Page, 25-26. 25 de Ségur, The Memoirs and Anecdotes of the Count de Ségur, 162. 9 Princess, who inaccurately gauged the importance of an occasion, offended the officers of the Garde Nationale, who then left the event “in a very bad humour and spread their discontent throughout Paris, increasing the ill-will which was being stirred up there against the Queen.”26 Only one of many such events, the Queen’s ignorance led to her rising unpopularity, spread by the Court to the people. Though the Revolutionaries saw themselves as breaking from the French Court, they both actually shared quite a few ideas about women, especially over the portrayal of Marie Antoinette. Her image suffered further blows by the revolutionaries who used her as a symbol of women in politics, a role that women could not play.27 Count de Ségur documented new political clubs that started to emerge. Drawing-rooms were transformed into “battling arenas” where the politically passionate flourished. He rightfully acknowledged that these clubs resulted in the separation of men and women.28 According to Count de Ségur, women were not suited to politics.29 Many men during this time, especially the revolutionaries, who closely followed the ideals of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, agreed. Rousseau, and the revolutionaries he influenced, believed women must remain confined to the domestic sphere. In his Émile or Treatise on Education, Rousseau clarified women’s duties, claiming, “The obedience and fidelity which she owes to her husband, the tenderness and care which she owes to her children, are such natural and obvious consequences of her condition, 26 Dillion, Memoirs of Madame de La Tour du Pin, 122. 27 Both the Princess Lamballe and Lynn Hunt make references to the fact that women were not allowed, by law, to rule in France. The Princess Lamballe calls these laws the “Salique Laws”. For an interesting look at the Salic Laws, see M. de Secondat, The Spirit of Laws, trans. Thomas Nugent (London: George Bell and Sons, 1878). 28 de Ségur, The Memoirs and Anecdotes of the Count de Ségur, 156. 29 de Ségur, The Memoirs and Anecdotes of the Count de Ségur, 277. 10 that she can not, without bad faith, refuse her consent to the inner sense which guides her…”30 Essentially, a woman’s place remained at home, leaving the man free to participate in the public. Rousseau warned that women in the public sphere, who wanted equality and could not “make themselves into men”, would then “make us into women”.31 The revolutionaries wanted to keep these gender roles the same, thus causing them to reject any feminine influence in the public sphere, including the Queen. Through spite and slander, the revolutionaries turned Marie Antoinette into a warning to other women entertaining ideas of using popular sovereignty to influence men the way they thought Marie Antoinette influenced the King through her role as Queen.32 The revolutionaries believed that Marie Antoinette influenced the king by teaching him how to dissimulate, or in other words, how to be corruptive and two-faced.33 Yet, when comparing the revolutionaries’ beliefs with the accounts of those close to the Queen, one wonders how much influence she actually exercised over Louis XVI. Accounts regarding Marie Antoinette’s political influence claimed that she did not wish to participate altogether. D’Hezecques believed Marie Antoinette’s “influence” actually consisted of her straightforward advice to the King. In fact, he claimed that the King often came to her for it.34 The Duc de Lauzun, a military commander and peer of France, detailed in his Memoirs of the Duc de Lauzun an event in which the Queen was told of a plan that would place M. le Comte d’Artois on the throne of Poland. According to Lauzun, Marie Antoinette, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Rousseau’s Émile or Treatise on Education, trans. William H. Payne (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1895), 279-280. 30 31 Hunt, “The Many Bodies of Marie Antoinette,” 204-205. 32 Hunt, “The Many Bodies of Marie Antoinette,” 215. 33 Hunt, “The Many Bodies of Marie Antoinette,” 202. 34 D’Hezecques, Recollections of a Page, 28. 11 “[L]istened to him with embarrassment and agitation, and answered him coldly that she did not wish to meddle with affairs of state.”35 His portrayal of Marie Antoinette’s reluctance directly opposes the accusations that she deliberately corrupted and influenced her husband in political affairs. The Princess Lamballe reinforces this point, saying, “[S]he never even thought of entering into State affairs till forced by the King’s neglect.”36 A supporter of women confined to domestic spheres, the Princess Lamballe identified this forced involvement as the factor that increased the public feeling from dislike to hatred of the Queen.37 In conclusion, the falsification of Marie Antoinette’s image originated with the biases held against her by the French Court, as well as the revolutionaries wish to use her as a symbol. The fear of foreigners, ignorance, and the notion that women should not be politically influential led to the inaccurate portrayal of Marie Antoinette. The research that has led to this conclusion has also produced new questions that need answering. Did Maria Theresa (Marie Antoinette’s mother) have other motives, besides strengthening the Austrian-French alliance, for sending her daughter to marry Louis XVI? Perhaps Maria Theresa did hope to gain control over France, which would have made Marie Antoinette a mere pawn, and would provide more support for why Marie Antoinette received such harsh treatment. Regardless, hopefully readers will come to understand how Marie Antoinette’s negative image was founded on biased individual’s accounts of the unfortunate Queen. 35 Memoirs of the Duc de Lauzun, trans. CK Scott Moncrieff (London: George Routledge & Sons, LTD., 1928), 182. 36 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, 43. 37 Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe, 155-156. 12 Bibliography Primary Sources Antoinette, Marie. Secrets of Marie Antoinette: A Collection of Letters. Edited by Olivier Bernier. New York: Doubleday, 1985. Blanc, Olivier. Last Letters: Prisons and Prisoners of the French Revolution, 1793-1794. Translated by Alan Sheridan. London: Andre Deutsch, 1987. Claude, Florimond. The Guardian of Marie Antoinette: Letters From the Comte de MercyArgenteau, Austrian Ambassador to the Court of Versailles, To Marie Thérèse, Empress of Austria 1770-1780. Edited by Lillian C. Smythe. London: Hutchinson & Co, 1902. D’Hezecques, Felix. Recollections of a Page at the Court of Louis XVI. Edited by Charlotte M. Yonge. London: Hurst and Blackett, 1873 de Ségur, Louis-Philippe. The Memoirs and Anecdotes of the Count de Ségur. Translated by Gerard Shelley. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1928. Dillion, Henriette-Lucy. Memoirs of Madame de La Tour du Pin. Edited and Translated by Felice Harcourt. New York: The McCall Publishing Company, 1971. Memoirs of the Duc de Lauzun. Translated by CK Scott Moncrieff. London: George Routledge & Sons, LTD., 1928. Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Rousseau’s Émile or Treatise on Education. Translated by William H. Payne. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1895. Secret Memoirs of Princess Lamballe. Edited by Catherine Hyde. Washington: M. Walter Dunne, 1901. Vizetelly, Henry. The Story of the Diamond Necklace: Told In Detail For the First Time. London: Vizetelly & Co., 1881. Secondary Sources Belloc, Hilaire. Marie Antoinette. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924. Castelot, Andre. Queen of France: A Biography of Marie Antoinette. Translated by Denise Folliot. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957. Cronin, Vincent. Louis and Antoinette. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1975. 13 Erickson, Carolly. To the Scaffold: The Life of Marie Antoinette. New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc., 1991. Fay, Bernard. Louis XVI or The End of a World. Translated by Patrick O’Brien. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1966. Fraser, Antonia. Marie Antoinette: The Journey. New York: Doubleday, 2001. Haslip, Joan. Marie Antoinette. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987. Hunt, Lynn. “The Many Bodies of Marie Antoinette: Political Pornography and the Problem of the Feminine in the French Revolution.” In The French Revolution: Recent Debates and New Controversies, edited by Gary Kates, 201-19. New York: Routledge, 2006. Jackson, Catherine Charlotte, Lady. The French Court & Society: Reign of Louis XVI and First Empire. London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1881. Kaiser, Thomas E. “From the Austrian Committee to the Foreign Plot: Marie-Antoinette, Austrophobia, and the Terror.” French Historical Studies 26, no. 4 (Fall 2003): 579-617. http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/journals/french_historical_studies/v026/26.4 kaiser.pdf (accessed 3/31/09). Kaplow, Jeffery. France on the Eve of Revolution. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1971. Landes, Joan B. Women and the Public Sphere: In the Age of the French Revolution. London: Cornell University Press, 1988. Lever, Evelyne. Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France. Translated by Catherine Temerson. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000. Maza, Sarah. Private Lives and Public Affairs: The Causes Célèbres of Pre-Revolutionary France. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. Price, Munro. The Road From Versailles: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and the Fall of the French Monarcy. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002. Savage, Gary. “Favier’s Heirs: The French Revolution and the Secret du Roi.” The Historical Journal 41, no. 1 (March 1998): 225-258. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy. umw.edu:2048/stable/pdfplus/2640151.pdf (accessed 3/31/09). Seward, Desmond. Marie Antoinette. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981. Thomas, Chantal. The Wicked Queen: The Origins of the Myth of Marie-Antoinette. Translated by Julie Rose. New York: Zone Books, 1999. 14 Tschudi, Clara. Marie Antoinette. Translated by E. M. Cope. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Lim., 1902. Weber, Caroline. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2006. Webster, Nesta Helen. Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette Before the Revolution. London: Constable and Company, ltd., 1936. Wick, Daniel L. “The Court Nobility and the French Revolution: The Example of the Society of Thirty.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 13, no. 3 (Spring 1980): 263-284. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.umw.edu:2048/stable/pdfplus/2737985.pdf (accessed 3/31/09). Younghusband, Lady. Marie-Antoinette: Her Early Youth. London: MacMillan and Co., Limited, 1912. Zweig, Stefan. Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of an Average Woman. Translated by Eden and Cedar Paul. New York: Viking Press, 1933.