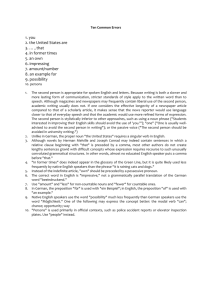

Essays on the Origins of Western Music

advertisement

Essays on the Origins of Western Music by David Whitwell Essay Nr. 122: On Music of the Courts of Spain Among the Aragon kings, the first to establish an important musical body within his court was Jaime II (1291 - 1327). He hosted visiting musician from Europe as well as Muslim minstrels. The historian Angles gives Jaime’s own ensemble as “trompes, trumpets, tambor, viula, xebeba [fluate] and meocanon der Araber.”1 The following leaders, Alfonso IV and Pedro IV were more inclined to Moorish musicians, but Juan I (1350 – 1396) began to import players from Western Europe, such as the shawm player, “Jaquet of Paris.”2 As early as 1391, Aragonese court musicians were traveling to Germany to buy instruments and the recruit Higino Angles, “Die Instrumentalmusik bis zum 16. Jahrhundert in Spanien,” in Natalicia Musicoolgica (Oslo, 1962), 148. 2 Edmond Vander Straeten, La Musique aux Pays-Bas avant le XIXe Siecle, (New York, 1969), VII, 72. 1 1 German musicians to take back.3 Juan was also a composer and a well-known gourmet who could eat four partridges at a single sitting.4 Alfonso V (1416-1458) had an ensemble of fifteen, including both strings and winds. In 1423, when visiting Paris, he heard a wind ensemble apparently belonging to Philip the Good and the latter made him a gift of the entire ensemble! Among the aristocratic entertainments of this period, perhaps the most documented were those surrounding the marriage of the king of Castile, Enrique IV, in 1440. Most notable, the host, the count of Haro, had constructed in a large field near his palace a kind of fifteenth century Disneyland. An entire forest was transplanted, together with puzzled deer, boars and bears and a nearby man-made lake was stocked with fish. Behind the lake a huge temporary building of twenty levels was built, with each level carpeted with green sod. The guests took their places on the various levels and enjoyed a great banquet, while watching hunters kill the helpless game in the artificial forest and anglers pull fish from the lake. After the meal, the party danced until breakfast, when each lady found a gold ring set with jewels by her plate. We are happy to report the count also distributed two great sacks of coins to the exhausted musicians.5 After the wedding party continued on to Valladolid, a great tournament was scheduled. This tournament got out of hand, as was sometimes the case, and turned into a bloodbath. This, plus the necessity for a public beheading and the occurrence of a number of (natural) aristocratic deaths, ruined the festive mood and caused the remainder of the entertainments to be canceled. Enrique’s royal trumpeters also played a role in the final event of this great wedding celebration. It was their duty to announce to the court, by way of a fanfare, the moment the royal bride ceased to be a virgin. They were placed by the door of the bridal chamber and three notaries were required by law to stand by the bed (beyond curtains, we presume!), ready to pass the word on to the trumpeters. H. Angles, “Musikalische Beziehungen zwischen Deutschland und Spanien in der Zeit vom 5. bis 14. Jahrhunderts,” in Archiv fur Musikwissenschaft (1959), XVI, 5. 4 Gustave Reese, Music in the Renaissance (New York: Norton, 1959), 575. 5 Townsend Miller, Henry IV of Castile (New York, 1972), 22. 3 2 Regretfully we report that on this occasion the trumpets never played, and thus history has awarded Henry the sobriquet, “the Impotent.” The next big ceremonial occasion of Henry’s reign was the investiture of Lucas as Constable of Castile in 1458. One reads that “whole choirs of silver trumpets”6 played and one eye-witness mentioned that the instruments also performed inside the church.7 An account of a welcome given Henry by Lucas in Jaen reports “platoons of silver trumpets” and “huge copper drums slung from Arabian horses and gleaming and pounding, cymbals….”8 Fernando V (1474-1516) and Isabella (1474-1504), patrons of Columbus, maintained separate musical establishments, reflecting their Aragonese and Castilian backgrounds even though they successfully united these kingdoms. Ferdinand had only 6 musicians in 1491, but a full 11 members in his wind band in 1511. After his noon meal, his secretary reports, there was string music. This morning his highness attended Mass in the church, as usual, after eating there was vihuela music, after which he went to Vespers.9 After the death of Isabella, in 1504, Ferdinand united the musical organizations. Isabella employed a wind band (Menestriles Altos), some 70 singers,10 strings and several organists. Indications are that Isabella was no indifferent listener to her musicians. If anyone of those who were saying or singing the psalms, or other things of the church, made any slip in diction or in the placing of a syllable, she heard and noted it, and afterwards -- as teacher to pupil -- she emended and corrected it for them.11 For her leisure, as well, Isabella enjoyed music, especially private “concerts” while she and her ladies worked at needlepoint.12 She gave a high priority to the musical education of her children, influenced by a book Vergel de Prencipes by Ruy 6 Ibid., 102. H. Angles, “La musica en la corte del rey Don Alfonso V de Aragon,” in Gesammelte Aufsatze zur Kulturgeschichte Spaniens (1940), 152. 8 Miller, Op. cit., 147. 9 Tess Knighton, ÒThe Spanish Court of Ferdinand and Isabella,Ó in The Renaissance (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1989), 343. 10 Henry Sullivan, Juan del Encina (Boston: Twayne, 1976), 129. 11 L. Marineus Siculus, De las cosas memorables de Espa–a (1539), 182v. 12 Sullivan, Op. cit., 129. 7 3 Sanchez de Arevalo, which argued for the ability of music to foster moral virtue, including the preparation for political leadership. One of her children, Juan, who died in 1497, was an active performer, as we see in an account by a contemporary, Gonzalo de Oviedo. My Lord prince Juan was naturally inclined to music and he understood it well, although his voice was not as good as he was persistent in singing; but it would pass with other voices. And for this purpose during siesta time, especially in summer, Juan de Anchieta, his chapel master, and four or five boys, chapel boys with fine voices, who went to the palace, and the prince sang with them for two hours, or however long he pleased to, and he took the tenor, and was very skilled in the art.13 This same source reveals that Juan owned a number of instruments, which he also played. Philip I of Spain (1504-1506), son of the famous Maximilian I married Juana, the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. True to his Burgundian heritage, Philip apparently loved music and brief though his reign was, there is considerable documentation for his musical establishment, in part due to accounts of his constant travel. On his first trip to Spain, in 1501, he took his singers, 9 trumpeters (who appear to have a broad mix of international names), 4 sackbuts (hired for the trip) percussion and, interestingly, 3 musettes.14 During the numerous musical performance he heard on his arrival in Madrid was a mass during which he heard the famous cornettist, Augustin, performing with the singers in the church.15 When Philip appears in France the following year it appears that he had hired away Augustin for he was now among the musicians of Philip. Another interesting account regards Philip’s trip from France to Spain in 1506. Now he traveled with 12 trumpets, an ensemble of 10 “Players of Instruments” and his church singers -- who apparently had their own ship.16 The instrumentalists were distributed on the other ships to provide entertainment, as 13 Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, Libro de la camara real del principe don Juan (Madrid, 1870), 182ff. 14 Vander Straeten, Op. cit., VII, 149. 15 Ibid., VII, 153ff. 16 Ibid., VII, 163ff, where the names of the musicians are given. 4 one eyewitness remembered, “it was fine to hear trumpets, drums, and other instruments all around on the ships.”17 The story become tragic for Philip died at age 26. His wife, Juana (known to history as “mad Juana”) was a very strong, outspoken woman, a woman of much character. This, of course, was not to be permitted of a woman in 16th century Catholic Spain. So, the Church had her locked in a cell with no windows and a single candle for the next 50 years. Even her family were sufficiently fearful of the Church that they never visited her. And for all this, she was the mother of two future emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, Charles V and Ferdinand I. Charles, the son of Philip and Juana, was born a descendant of the house of Hapsburg was still a child when his father died. His aunt, Margaret of Austria served as regent in his place and after a very complex series of political events he became first Charles I, king of Spain, and then Charles V, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He had a slow start in his development but soon made rapid progress, learning several languages and personally hiring Erasmus to be an ornament of his court. In 1517 he traveled to Spain to assume the throne, taking with him singers and his wind band. He was welcomed in each major city as he traveled and we have an eye-witness from his welcome in Valladolid. First were twenty timpani (of the princes and great men of Castile), mounted on mules, making a great noise. Afterward came twenty-eight Spanish trumpets, followed by the twelve trumpets of Charles, all dressed in sleeveless violet tunics covered with little silver and gold letter C’s sown on. Later came twelve more timpani and twelve trumpets.... [When Charles presented himself in the field], first came thirty tambours on horse and two large tambours. Next came sixty more drums on foot as well as forty trumpets from Castile, Naples, and Aragon, making so much noise you could not have heard the thunder of God. Next came the twelve trumpets of Charles playing in “bon art et mode.” Finally came ten German tambors on foot, and six fife players of German flutes.18 17 Van Doorslaer, La Chapelle, quoted in Louise Cuyler, The Emperor Maximilian I and Music (London, 1973), 69. 18 Edmond Vander Straeten, Op. cit., VII, 289ff. 5 Not content, at age 19, to be king of Spain, Charles now began his successful campaign to become emperor. One diplomat who knew him at this time reported to Pope Leo X, This prince seems to me well endowed with…prudence beyond his years, and to have much more at the back of his head than he carries on his face.19 Today we would say, “He is smarter than he looks.” As emperor, Charles traveled frequently around Europe on political trips and there are a number of accounts of his being welcomed by massed trumpets. Usually these accounts are not musically interesting, but one, on his arrival in Valenciennes in 1540, included a performance of his own 20 trumpets “playing very melodiously.”20 By 1555 his health was failing and he resigned his titles. Upon his death the inventory of the estate included a very large number of string and wind instruments.21 Philip II, who inherited the great power of Charles V, came at a time, chronologically, when Spain was beginning to decline as a power. He also traveled a lot and on a trip to Flanders, Italy and Germany in 1548 he took 17 singers, a 10 member wind band and 2 cornetts. He was the protector of the Church in Spain and the good Catholics there joined those n France in celebrating the infamous St. Bartholomew massacre. With anthems in St. Gudule, with bonfires, festive illuminations, roaring artillery, with trumpets also, and with shawms, was the glorious holiday celebrated in court and camp, in honor of the vast murder committed by the Most Christian King upon his Christian subjects….22 Since there seem to be no accounts which speak of any particular interest in music, other than the ceremonial music he needed at all times, the very large instrument collection left at the time of his death may well represent some inherited instruments from his father, and even perhaps his grandfather. The collection included, 19 Quoted in Edward Armstrong, The Emperor Charles V (London, 1910), I, 69. Vander Straeten, Op. cit., VII, 381. 21 Archives generales de Simancas, Contaduria mayor, Nr. 1017, fol. 162ff. 22 John L. Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic (New York, 1864), II, 393. 20 6 11 keyboards 47 lutes and string instruments 6 ivory fifes, 4 small and 2 large 6 box-wood fifes 6 ivory fifes 7 German fifes of rough wood 8 German fifes of wood 14 German fifes, of which 4 are large fifes of various dimensions 7 large German wood flutes 2 large flutes, 3 small ones, 2 fifes a box-wood flute 4 ivory cornets a bouquin contrabass cornett a bouquin 4 wood German cornets, 2 large and 2 small 7 wood German cornets 6 wood German cornets, to be played with the silver sackbuts 5 wood German cornets, large and small 2 black cornets an ivory cornett an ivory shawm a wood German shawm of great dimension contrabass shawm 2 small wood German shawms a wood German shawm, same as the others, known as a “bajon” a bassoon of very great dimension, the contrabass of the flutes a very large box-wood bassoon, contrabass of the flutes a large bassoon of box-wood contralto fagot a box-wood doucaine 16 wood German cornemuses [crumhorns] 2 bagpipes [tudelos] 4 silver sackbuts, with keys a silver sackbut of great dimension a soprano sackbut a brass sackbutt 7