Candler_TolkeinNietz.. - Centre of Theology and Philosophy

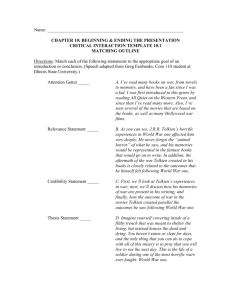

advertisement