Comparison-Contrast Essay Example.doc

advertisement

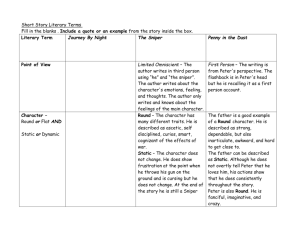

Name Date Teacher Class The Face of Humanity “War is like love, it always finds a way” (Bertolt Brecht). Although one is evil and the other pure, the powerful forces of both war and love inspire the best stories. An even more interesting topic emerges when a character must chose between devotion to a war and loyalty to loved ones. In both Liam O’Flaherty’s “The Sniper” and Hwang Sunwon’s “Cranes,” the main character is involved in a civil war that calls for his allegiance to the government despite his feelings for a loved one who fights for the enemy. Even though these stories share the subject of civil war, their themes differ greatly. Whereas “The Sniper” reveals the inhumanity that results from civil war, “Cranes” focuses on wartime opportunities for heroic acts that value humanity. In “The Sniper,” the protagonist learns an unbearable lesson about the gruesome nature of war when he unveils the identity of the man he killed. The unnamed sniper represents a young Irish man who is consumed by the 1920 politics of the Republicans who want to free Ireland from British rule. Liam O’Flaherty writes, “His [the sniper’s] face was the face of a student, thin and ascetic, but his eyes had the cold gleam of the fanatic. They were deep and thoughtful, the eyes of a man who is used to looking at death” (212). Therefore, the pervasive war transformed this once innocent and rational young man into a heartless extremist. With his devotion to a political cause and the need for survival, the sniper lies on a rooftop near the Four Corner of Dublin and faces an external conflict with a Free Stater sniper who is staked out on a near building. The sniper is in a kill or be killed situation. After masterfully killing his enemy and rejoicing in his victory, “the sniper…shuddered. The lust for battle died in him. He became bitten by remorse” (214). The sniper learns that he has given into the brutality of war that he hates so much, yet he does not understand the full measure of his mistake. As the sniper rolls over the dead body, he unveils the face of his brother. He painfully learns that his lust for battle and devotion to a cause has spurred him to kill his brother. Only now does the desperate theme resound: inhumanity results from civil war. Contrarily, Songsam, the protagonist in “Cranes,” learns an uplifting lesson about the triumph of heroism and humanity when he capitalizes on a wartime opportunity. The story opens with Songsam, a South Korean soldier in the 1950s civil war, residing in his former hometown. Sunwon writes, “The village as a whole showed few traces of destruction from the war, but it did not seem like the same village Songsam had known as a boy” (222). Although the war has not changed the land significantly, it has impacted Songsam, darkening his outlook on life. When Songsam spots a boyhood playmate and former vice-chairman of the Communist League, Tokchae, his bitterness towards the northern communists motivates him to escort his friend to his death. Songsam declares, “You [Tokchae] are sure to be shot anyway” (224). Despite his initial certainty, Songsam undergoes a change of heart when he reminisces about his days spent crane trapping with Tokchae. Now, Songsam is torn internally between his loyalty to the government and his loyalty to a friend. As he fondly recalls the day he and Tokchae released a crane in danger, Songsam learns that his friendship is stronger than the war that threatens to divide it. He craftily unbinds Tokchae to crane trap, allowing Tokchae to escape. As Sunwon ends the story by comparing Songsam and Tokchae to two liberated cranes, the theme resounds: wartime opportunities allow for heroic acts that value humanity. Whereas “The Sniper” focuses on the hopeless message that wartime provokes extreme inhumanity, “Cranes” conveys a hopeful message that individuals can choose compassion over violence, even during wartime. As each story opens, both protagonists are consumed by the animosity that fuels war. Immediately, they face conflicts that force them to consider killing another man. Driven by both devotion to a cause and survival, the sniper unknowingly kills his brother and confirms that war makes men do inhumane deeds. Contrarily, Songsam has time to dwell on his past and consider the value of his prisoner’s, and friend’s, life, and he sends the message that humanity can triumph during the heat of civil war. Perhaps the difference between life and death, humanity and inhumanity, is the ability to step back from a wartime situation and evaluate one’s loyalties, morality, and love for mankind.