1. Hannibal Lecter and the Gothic Tradition

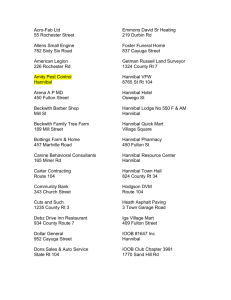

advertisement