Reasonable legal costs

advertisement

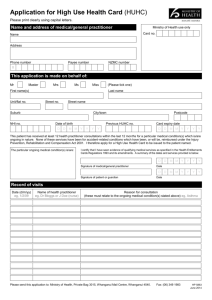

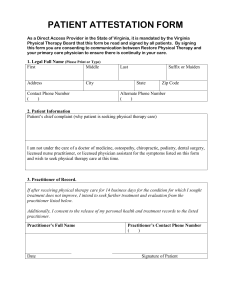

4 November 2009 COAG National Legal Profession Reform Discussion Paper: Legal Costs Introduction Australia’s legal market primarily services two broad categories of client: retail consumers, who tend to be infrequent purchasers of legal services; and sophisticated or institutional clients who generally are repeat purchasers and experienced commercial operators.1 Each group has different levels of familiarity with legal processes and different levels of bargaining power in relation to legal costs. The Standing Committee of Attorneys-General recognised this in approving separate costs disclosure and assessment regimes for sophisticated and retail clients under the national legal profession model legislation (‘Model Bill’). While sophisticated clients usually are able to negotiate their legal costs based on previous experience in similar matters and commercial decisions about the value of the work to their business, retail consumers generally have less experience or information when engaging a legal practitioner or law practice. The complex and specialised nature of legal work also means that retail consumers can have limited capacity to determine whether work is necessary or valuable. This ‘information asymmetry’ can disadvantage retail consumers in their relationship with their lawyer—often at times when clients are in a state of heightened sensitivity and pressed to make urgent and significant life decisions. The lack of market-based or scientific methods for valuing legal costs, and the costs of changing representation, can result in retail clients being charged more than reasonable costs for legal services, or create a perception of overcharging. Clear, concise and timely costs disclosure is a good business practice: it minimises the potential for misunderstandings at a later stage, and the possibility of complaints against lawyers where a client feels he or she has been charged more than is fair and reasonable. Early discussions about costs help to educate clients about how the legal process works, and can assist in focusing them on the desired outcome and the way the matter should be progressed to achieve it. This facilitates greater control by clients over their own legal matters and can result in greater clarity about the shared goals of the client and lawyer. Costs disclosure also benefits the legal profession as a whole. Although complaints about costs disclosure and overcharging are made against a small proportion of the profession, costs complaints continue to be a primary ground of complaint in all States and Territories. Costs complaints can have a disproportionately negative impact on the profession’s reputation, obscuring its positive contribution to the community. Therefore, by reducing the potential for disagreements about legal costs, mandatory disclosure serves the interests of the broader profession by helping to maintain public confidence in it. Regulatory oversight of legal costs can also be justified because lawyers enjoy a monopoly on the provision of most legal services. Independent review of legal costs therefore is a reasonable counter-measure to the maintenance of restrictions in market competition within this sector. Mandatory costs disclosure was introduced in the 1990s to off-set the deregulation of legal fees, 1 There are also a small group of high-net worth individuals who do not fall within the statutory definition of ‘sophisticated client’, but who are experienced commercial operators; and clients who primarily access the justice system through legal aid and community legal centres. which provided more freedom, flexibility and competition in fee charging for legal practitioners than the previous system of scales of costs.2 However, while broad public interests require that all legal practitioners should be subject to a general obligation to charge only fair and reasonable legal costs, not all clients require the same level of consumer protection. The Taskforce proposes to maintain the existing approach that allows sophisticated clients to contract out of the mandatory costs disclosure and assessment regimes. SCAG proposals In April 2009, the Standing Committee of Attorneys-General noted a number of NSW proposals to constrain overcharging and exploitation of vulnerable legal services consumers, and asked a joint working party to make recommendations as to their adoption in the national model law. The proposals were as follows. Strengthening the existing provision that a written disclosure to a client may be in a language other than English if the client is more familiar with that language; Requiring law practices to provide periodic, itemised bills to clients in personal injury matters; Prohibiting law practices from seeking clients’ authorities to deduct legal costs from a settlement amount without having first informed the client of the settlement amount and issued the client with a bill (which must be itemised in personal injury matters); Providing that a bill or covering letter must be signed by a principal of a law practice (rather than a legal practitioner or other person); and Prohibiting law practices from charging excessive costs in a legal matter, and providing a financial penalty for breach of this provision without a reasonable excuse. SCAG subsequently referred these matters to the Taskforce for consideration as part of this reform process. The proposed legislative principles The following legislative principles are proposed for the costs regime. These would be included in the National Law, and would be complemented by National Rules. Objectives of the scheme The purposes of this scheme are as follows: to provide for law practices to make disclosures to clients regarding legal costs; to regulate the making of costs agreements in respect of legal services, including conditional costs agreements; to regulate the billing of costs for legal services; to provide a mechanism for the assessment of legal costs and the setting aside of certain costs agreements. Costs disclosure Before, or as soon as practicable after, giving instructions to act clients shall receive sufficient written information about the estimated costs of their matter, and the method for calculating that estimate, to reasonably allow them to make informed decisions about the conduct of the matter. This shall also include disclosure in relation to costs where a law practice intends to retain another law practice or expert on behalf of the client. 2 A Lamb and J Littrich, Lawyers in Australia (2007), 215. 2 Any significant change to a matter previously disclosed must be notified to the client as soon as reasonably possible after the law practice becomes aware of the change. Costs disclosure should be presented in a concise, clear and accessible format. Legal practitioners should take reasonable steps to ensure that clients understand the information disclosed. In addition, consumers from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds should not be disadvantaged as compared to people for whom English is their first language. Clients must be informed about their right to negotiate a costs agreement and to challenge legal costs. Costs agreements are enforceable as a contract between the parties (and any assessment will by reference to the costs agreement if it is a valid agreement complying with the legislation). If a law practice fails to disclose anything required by the legislation, the client will not be required to pay legal costs until they have been assessed. The law practice must not commence or maintain proceedings to recover fees until after the assessment. Sophisticated clients may contract out of the mandatory costs disclosure and assessment regimes. Reasonableness Legal practitioners and law practices may only charge fair and reasonable costs. A costs agreement is prima facie evidence of what are fair and reasonable costs. Legal costs should be proportionate to the complexity or importance of the issues and amount in dispute. Law practices and their clients may agree to a variety of methods for calculating legal costs. The courts and tribunals may set aside costs agreements, in whole or in part, which are not fair or reasonable. Legal practitioners and law practices must make reasonable endeavours to act promptly and to minimise delay in the legal process and must not otherwise work in a way that unnecessarily increase costs in a matter. Billing A law practice may not seek to recover its fees unless it has provided a properly prepared bill to the client. A law practice may not charge for the preparation of bills and clients may request an itemised bill (at no additional cost). Bills must include a notice about a client’s right to challenge legal costs or to have a costs agreement set aside. 3 Liability of principals for overcharging Principals of law practices are responsible for the reasonableness of bills rendered to clients, and will be personally liable in the event of the charging of excessive legal costs in matters in which they have acted or which they have supervised. A law practice may be liable for the charging of excessive legal costs by one of its principals or one of its employees. Cost assessment Costs assessments must be conducted in accordance with National Rules. Determinations of costs assessors are admissible in disciplinary proceedings as evidence as to the reasonableness of legal costs. Regulatory Guidelines The Board shall issue National Rules detailing actions that practitioners are required to take to comply with these legislative principles, and to give effect to these legislative principles. A breach of the National Rules will be conduct capable of constituting unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct. In the case of law practices, a breach without reasonable excuse may constitute an offence. Discussion Several of these proposed legislative principles are not currently included in the Model Bill. The following provides a brief discussion of the policy arguments for their inclusion in a new costs regime. Level of detail in disclosure A criticism of the mandatory disclosure regime is the lack of guidance about the level of detail required in disclosure documents. It is argued that practitioners are either legally required to, or regularly err on the side of, caution and provide voluminous detail in costs disclosure documents for fear of failing to meet their professional obligations. Overwhelmingly detailed disclosure does not serve the interests of either practitioner or client and was not intended when the regime was introduced. The aim of costs disclosure is to provide the parties with a starting point from which to begin a dialogue about costs. Written disclosure should be a high-level summary to which the client can refer when making decisions during the course of a legal matter—it is not expected to be a detailed document providing substantive legal advice on legal rights and options (although it should complement that advice when later provided). It should be made clear that practitioners are only required to take reasonable steps in providing mandatory disclosure. Disclosure in languages other than English The Model Bill currently provides that written disclosures to a client may be in languages other than English if a client is more familiar with that language. A more positive obligation could imposed to ensure that clients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds understand the information being disclosed. Accordingly, in addition to this provision about written disclosures, there could be an additional requirement that a legal practitioner be reasonably satisfied that the client understands the costs disclosure given. In practice, this would mean that where necessary a legal practitioner (or, where this is not practicable, the client) would need to obtain a translator to explain the costs disclosure to the client. 4 The Taskforce does not consider this proposal to be unduly onerous given that the legal practitioner would in any case be required to ensure that he or she is able to communicate effectively with a client in order to obtain ongoing instructions in a matter. Proportionality in assessing reasonableness of costs Proportionality of legal costs is already enshrined in certain areas. For example, section 60 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW) provides that: ‘in any proceedings, the practice and procedure of the court should be implemented with the object of resolving the issues between the parties in such a way that the cost to the parties is proportionate to the importance and complexity of the subject-matter in dispute’. In Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2007] FCA 1062, Justice Sackville commented adversely on the disproportionate amount of the legal fees relative to the amount ultimately in dispute.3 His Honour has subsequently commented that ‘… there is an undeniable public interest in the courts actively applying the principle of proportionality to all forms of litigation, whether the stakes are very high or comparatively low. If this is not done, judges can hardly be surprised if the civil courts are largely seen as the exclusive domain of the wealthy and powerful’.4 The Victorian Law Reform Commission discussed the issue of proportionality in its report, Civil Justice Review (2008). The Commission noted certain difficulties in applying the principle of proportionality to legal costs. However, it recommended that new provisions should be enacted in respect of certain matters, including a paramount duty on parties, legal practitioners and law practices involved in civil proceedings to the court to further the administration of justice; and this would include a duty to ‘use reasonable endeavours to ensure that the legal and other costs incurred in connection with the proceedings are minimised and proportionate to the complexity or importance of the issues and the amount in dispute’.5 Liability of principals for overcharging Under the Model Bill, bills must be signed on behalf of the law practice by a legal practitioner or other employee, and anything done by a legal practitioner on behalf of the law practice is deemed to have been done by the law practice. The Model Bill also deems any breach of the Act by a law practice to have also been committed by a principal unless he or she establishes that: the practice contravened the provision without the actual, imputed or constructive knowledge of the principal; or the principal was not in a position to influence the conduct of the law practice in relation to its breach of the provision; or the principal, if in that position, used all due diligence to prevent the breach by the practice. The Model Bill also provides that the charging of excessive legal costs in connection with the practice of law is capable of being unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct. However, the common law standard culpability for a finding of professional misconduct appears to require that the legal practitioner be personally implicated in the conduct that is the subject of the complaint.6 3 4 5 6 Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2007] FCA 1062, [8]-[10]. R Sackville, ‘The C7 Case: A Chronicle of a Death Foretold’, Paper presented to New Zealand Bar Association International Conference, 15 & 16 August 2008. Victorian Law Reform Commission, Civil Justice Review Report (2008), Rec 16.3. See the discussion in Nikolaidis v Legal Services Commissioner [2007] NSWCA 130. 5 In practice, difficulties could arise in identifying a particular legal practitioner against whom to bring any disciplinary proceedings where a law practice has engaged in excessive overcharging. For example, in many legal practices the preparation and provision of bills may be broken into multiple sub-tasks undertaken by different people, of whom some may be legal practitioners and some may not. It is possible that no one legal practitioner could be identified who has the necessary level of personal culpability for a finding of professional misconduct for charging excessive legal costs in connection with the practice of law. Depending on the circumstances, it might be possible to bring disciplinary proceedings for professional misconduct on other grounds, such as where a legal practitioner fails to supervise his or her staff in preparing or signing a bill. However, another approach would be to require principals of law practices to take responsibility for the content of bills sent to clients, including the reasonableness of the costs in them. The Taskforce considers this an appropriate option, and proposes that the National Law include principles to this effect (as outlined above), which could be complemented by National Rules as discussed below. Requirement to avoid delay A number of reports on civil law reforms have raised concerns about over-servicing and its impact on the overall cost of litigation. One proposal is the increased use of capped or fixed costs orders7 by courts, but over-servicing is also potentially a disciplinary matter. An obligation on practitioners to expedite the legal process would be consistent with practitioners’ broader duties to the courts to ensure that the administration of justice is timely and efficient and that costs are reasonable. It would also assist practitioners to resist requests from clients for unnecessary or surplus services. This kind of obligation was recently recommended by the Victorian Law Reform Commission, which recommended a duty on parties to civil proceedings, their legal practitioners and law practices to use reasonable endeavours to act promptly and to minimise delay.8 National Rules for legal costs Under the new regulatory framework, the National Legal Services Board will be responsible for developing uniform National Rules (ie, national binding rules) in relation to various areas of legal profession regulation. The Taskforce proposes that the National Rules deal with the following matters, and would be interested in the views of the Consultative Group and other stakeholders in relation to the proposals. Generally, the proposals are based on the relevant provisions of the Model Bill, and other measures that have been identified to address concerns with existing regulation. Under the Model Bill, disclosure largely only applies to retail clients (eg, individuals, families and small businesses) as ‘sophisticated clients’ are excluded from the costs disclosure regime. Therefore, the following suggestions are based primarily on addressing the needs of retail clients. 7 8 Orders which limit the total amount of costs recoverable in the matter by one party against another to a specified capped amount. Alternatively, courts might be given the power to fix costs at a particular rate for specified pieces of work undertaken in the proceedings (eg filing further and better particulars). Victorian Law Reform Commission, Civil Justice Review Report (2008), Rec 16.3. 6 Costs disclosure The National Rules should include the following matters, which are largely based on the existing Model Bill provisions. Mandatory disclosure Written disclosure must be made in writing before, or as soon as practicable after, the law practice is retained in the matter. Disclosure must be made to the client and any associated third party payer for the client (to the extent relevant). There should be exemptions from the mandatory disclosure requirements where the total legal costs in the matter are not likely to exceed a certain amount;9 the client is a sophisticated client and has agreed in writing to waive the right to disclosure; or the client is one of a certain class of client for whom the Board considers on reasonable grounds to be a sophisticated client or for whom mandatory disclosure is otherwise unnecessary. Form of disclosure Written disclosures to a client must be expressed in clear plain language; may be in a language other than English if the client is more familiar with that language;; and if the law practice is aware that the client is unable to read, the law practice must arrange for the required information to be conveyed orally to the client in addition to providing the written disclosure. Nature of disclosure The mandatory disclosure should include: The basis on which legal costs will be calculated, including the things to be billed for (eg photocopying etc); The client’s rights in relation to costs, including the right to negotiate the basis of costs; receive periodic bills from the law practice; request an itemised bill; and be notified of any substantial change to the matters previously disclosed; An estimate of the total legal costs if reasonably practicable, or else a range of estimates of the total legal costs and an explanation of the major variables in them; The rate of interest (if any) that the law practice charges on overdue legal costs; The client’s right to make reasonable requests for progress reports (which may include a written report of the legal costs incurred to date or since the last bill, at no cost to the client); The avenues for disputing legal costs, the process for following them, and any time limits that apply to any such action; If a law practice intends to retain another law practice, a barrister or an expert on behalf of a client, it must disclose that practice or person’s costs and billing arrangements;10 If there will be an uplift fee, there should be disclosure of the law practice’s legal costs; the uplift fee (or the basis of calculation of the uplift fee); and the reasons why the uplift fee is warranted. 9 10 Currently, NSW and Victoria require costs disclosure in matters where legal costs are likely to exceed $750, while other jurisdictions have adopted a $1,500 threshold. The Board should specify the appropriate monetary threshold in a National Rule. This proposal extends the current disclosure from law practices, to include an expert retained on behalf of the client. The NSW Legal Fees Review Panel recommended that: where a practitioner proposes to retain a third party expert, other than another legal practitioner; and the practitioner expects that that expert’s fees will exceed $1,000, the practitioner should be required to: obtain an estimate of the expert’s fees; provide that estimate to the client; and obtain the client’s consent prior to retaining the expert. However, an exception should be provided for urgent situations: NSW Legal Fees Review Panel, Report: Legal Costs in NSW (2005). 7 In relation to litigious matters, mandatory disclosure should also include: An estimate of the range of costs that may be recovered if the client is successful in the litigation; The range of costs the client may be ordered to pay if unsuccessful (and that a court order for costs in favour of the client will not necessarily cover all of the client’s legal costs); Where the client enters into a conditional costs agreement, that the client may be required to pay the law practice’s disbursements even if not required to pay legal costs. Impact of non-compliance Where a law practice does not comply with the disclosure requirements: The client need not pay the legal costs unless they have been assessed under the costs assessment provisions, and a law practice may not bring proceedings for the recovery of legal costs unless the costs have been assessed; The client may apply to have the costs agreement set aside and/or may make a complaint to the National Legal Services Ombudsman; The amount of the costs may be reduced by an amount considered proportionate to the seriousness of the failure to disclose; and Failure to comply with these provisions may be subject to appropriate penalties, and is capable of constituting unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct. Additional proposals The National Rules could also include provisions to deal with the following matters. A standard national costs agreement The NSW Legal Fees Review Panel proposed a standard form of costs disclosure as a way of making information about costs more accessible and transparent.11 A similar ‘standard form’ approach was adopted in the Model Bill in relation to standard disclosure requirements (eg, a summary of the right to challenge legal costs). Under the Model Bill, law practices may opt to meet their disclosure obligations by attaching the plain language fact sheets to their costs agreements. Accordingly, the Board should have the power to approve a single national costs agreement precedent, to be used as the basis for costs disclosure by law practices and legal practitioners (see example at Attachment A). Additional disclosure information could be included where necessary in the circumstances of the case. If a standard document were developed, translated versions could also be prepared. This would reduce the costs associated with proposals to strengthen the disclosure regime for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Nature of disclosure In addition to the existing requirement to inform a client about the potential risk of being ordered to pay the costs of the other side in a litigious matter, there should be a duty to disclose that the client’s own costs must be paid from the total amount of any settlement or damages award and may not be fully recovered from any party/party costs received. This would build upon existing disclosure obligations. Clients would be in a better position to make informed choices about their legal matter if they understood the costs implications of the various options presented to them. Estimates should be reasonable at the time at which they are given, but should be based on the practitioner’s professional judgement and experience. 11 NSW Legal Fees Review Panel, Report: Legal Costs in NSW (2005). 8 Requiring this disclosure up-front also protects the practitioner who can use the initial disclosure to reinforce to the client that certain strategies may have high cost implications. Disclosure of costs increases The National Rules should prohibit material changes to the method of charging legal costs in a legal matter (eg, by increasing hourly rates) unless written notice of, say, three months has been given prior to the increase and the client has given informed consent. If no disclosure is made, the law practice should be allowed to recover only at the rate in the original costs agreement or the last complying notice. The Taskforce would be interested in the views of the Consultative Group and stakeholders as to whether three months is a reasonable amount of time. Disclosure in litigious matters Generally, the Taskforce considers that the National Rules should require disclosure in litigious matters to be divided into estimates of a range of costs for: initial advice about rights and options; a pre-hearing settlement or equivalent; a standard contested hearing; and a complex/delayed hearing. As discussed above, SCAG has referred certain proposals in relation to legal costs to the Taskforce for its consideration. These proposals were developed in response to recent allegations of overcharging by legal practitioners that included failure to inform the client of the amount of damages paid in settlement of a claim; failure to deliver any bill in relation to costs deducted from settlement amounts; and settling claims without authority. The Taskforce notes that the Model Bill already provides that, if a law practice negotiates the settlement of a litigious matter, it must disclose to the client before the settlement is executed: a reasonable estimate of the amount of legal costs payable by the client (including any legal costs of another party); and a reasonable estimate of any contributions towards those costs likely to be received from another party. However, to ensure greater clarity for consumers of legal services in litigious matters, the Taskforce proposes that law practices also should be required to disclose an estimate of the costs to complete the matter if it settles, and should be prohibited from seeking clients’ authorities to deduct legal costs from a settlement amount without providing the minimum required information. Nature of determining costs The Taskforce notes that there is a range of ways in which legal costs could be determined in any legal matter. While ‘time billing’ has been adopted by a substantial part of the legal services market, other options include fixed or flat fee billing,12 capped fees,13 contingency fees and percentages,14 blended hourly rates,15 retrospective fees based on value,16 relative value,17 task 12 13 14 15 16 This involves the legal practitioner and client agreeing on a set fee for specified purposes. This involves setting a ceiling for all fees for a particular matter. For example, a law practice may charge an hourly rate for a particular matter, but may not exceed the agreed ceiling. This involves an agreement under which the legal practitioner will be paid in the event of a particular outcome, and an agreement to pay the legal practitioner a certain percentage of the final settlement. Under this arrangement, rather than each legal practitioner charging at his or her usual hourly rate, the law practice calculates a rate that is averaged across all of the employees who would work on the matter (including, in some cases, paralegal and secretarial staff), which is then charged for each of those employees. This involves determining the value of the work at the conclusion of the matter. 9 based billing18 and discounted billing.19 However, some of these proposals have also been the subject of certain criticism. Alternatives to time billing There has been significant debate in recent years about the dominant role of the billable hour in calculating legal costs. The NSW Legal Fees Review Panel listed the most common criticisms of time based pricing, being:20 Time based charging privileges quantity over quality. It rewards best those who take longest, regardless of what they produce. It allocates all major risk to the client. It discourages, by not rewarding, non-chargeable uses of time- such as education, community contributions, professional activities and perhaps most importantly of all, the active and detailed supervision of junior staff. It encourages increasing billable hours targets, since this is the easiest way to boost profits without encountering client resistance. It provides no incentive for speed or efficiency and arguably actively discourages both. It puts the client’s interest in a swift and efficient resolution directly in opposition to the lawyer’s interest in maximising hours and therefore income. It is unaffected by success, and therefore not conducive to improvement and excellence. The Panel also noted that time billing distances lawyers from any understanding of the real market value of their services.21 The Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department’s Access to Justice Taskforce raised the issue of legal costs in its recent report, A Strategic Framework for Access to Justice in the Federal Civil Justice System (2009). The Taskforce noted the benefits of increasing transparency in legal fees, suggesting that this would ‘allow people to make informed decisions about legal issues, taking into account whether a proposed course of action is proportionate in the circumstances’.22 The Access to Justice Taskforce also discussed the use of event billing for Commonwealth legal services. The Taskforce noted that some large corporations are using their market power to demand different fee structures, and more transparent and fair fees. Given that the Commonwealth is a large consumer of legal services, it suggested that it could be in a position to influence the culture of the legal profession in terms of billing. For example, it suggested that requiring firms to bill on an event basis would provide more certainty in Government legal purchasing and may encourage event billing in the wider community. The Access to Justice Taskforce recommended that:23 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 This involves the legal practitioner and client preparing a schedule of services that a broken down by subject matter and task, and attaching to each task an agreed relative value or multiplier. This involves billing according to particular tasks. The legal practitioner is asked to provide a budget before performing a particular task and may not (without prior agreement) exceed the budget. This involves providing a discount on a bill or a billing method (such as a discounted hourly rate) in consideration for, for example, a certain volume of business. In relation to these forms of billing, see generally, S Mark, ‘Analysing Alternatives to Time-Based Billing and the Australian Legal Market‘ (2007), Paper presented at the Finance Essentials for Practice Management Conference, Sydney, 18 July 2007. NSW Legal Fees Review Panel, Report: Legal Costs in NSW (2005), 14. Ibid, 15. Access to Justice Taskforce, A Strategic Framework for Access to Justice in the Federal Civil Justice System (2009). Ibid, Rec 9.4. 10 Commonwealth agencies should negotiate with legal service providers for the provision of legal services associated with litigation on an event basis—not time billing. For example, the Commonwealth could negotiate payment stages such as initial advice, pre-filing, filing, discovery, interlocutory, ADR, and final hearing stages. Agencies should provide a report to the Office of Legal Services Coordination on the outcome of such negotiations. This Recommendation could be implemented initially as a pilot. Where the Commonwealth is already engaged in cost saving billing practices such as a fixed fee arrangement, this should continue. The Taskforce recognises that the traditional costs disclosure regime may not adequately address the range of ways in which legal costs could be determined. In order to provide sufficient incentives to legal practitioners and clients to discuss and negotiate the most appropriate way to determine legal costs in a particular matter, the Taskforce proposes that the Board should have the capacity to develop National Rules where it considers it appropriate to do so which address matters such as mandatory costs disclosure, billing and costs assessments for these alternative forms of billing for legal services. Contingency fees The Model Bill currently prohibits contingency fee agreements, but permits conditional costs agreements providing for uplift fees of up to 25% of fees for litigious matters. The Taskforce would be interested in the views of the Consultative Group and stakeholders as to whether these provisions should remain under the National Law. Costs agreements Generally, the Taskforce proposes that the National Rules should include a simplified form of the Model Bill’s existing provisions regarding costs agreements. As with the Model Bill, the National Rules should provide that a costs agreement that breaches the statutory requirements is void, but that a practitioner can recover costs either under an applicable scale or according to the fair and reasonable value of the legal services provided. However, a law practice cannot recover any amount exceeding the amount it would have been entitled to recover under the costs agreement. Litigation funding Litigation-funders often provide funding on the basis that the costs recoverable from the litigant will be determined as a proportion of any award of damages. In several jurisdictions practitioners are prohibited from entering into contingency agreements in claims for damages. Generally, practitioners should not be able to avoid these prohibitions by taking a financial interest in a litigation-funder or by their associate or relative taking an interest. Accordingly, the Taskforce notes that legal practitioners could be prohibited from establishing corporate vehicles to provide litigation funding or entering into agreements with litigation funding vehicles owned by an associate of their law practice or a relative. The Taskforce would be interested in the views of the Consultative Group and stakeholders on this matter. Reasonableness of costs The overriding principle in relation to legal costs is that the costs charged for legal services should be fair and reasonable—regardless of the means by which the costs are charged. In addition, it would be appear appropriate to include a requirement that costs should be proportionate to the complexity or importance of the issues and amount in dispute. 11 The National Rules should include the following matters. Obligation to charge fair and reasonable costs Subject to exceptions in relation to sophisticated clients, law practices should have a duty to charge only fair and reasonable costs. The Model Bill currently does not include such a duty, but provides that legal costs are recoverable only under a complying costs agreement; in accordance with an applicable costs determination or scale of costs; or according to the fair and reasonable value of the legal services provided. In conducting a costs assessment, a costs assessor must consider: whether or not it was reasonable to carry out the work to which the legal costs relate; whether or not the work was carried out in a reasonable manner; and the fairness and reasonableness of the amount of legal costs in relation to the work (except in certain circumstances). In considering what is a fair and reasonable amount of legal costs, the costs assessor may have regard to any or all of the following matters: whether the law practice and legal practitioner complied with relevant legislation; any disclosures made; any relevant advertisement as to: the law practice’s costs; or the skills of the law practice or any legal practitioner acting on its behalf; the skill, labour and responsibility displayed on the part of the legal practitioner responsible for the matter; the retainer and whether the work done was within the scope of the retainer; the complexity, novelty or difficulty of the matter; the quality of the work done; the place where, and circumstances in which, the legal services were provided; the time within which the work was required to be done; and any other relevant matter. The Taskforce considers that placing a positive obligation on law practices to charge fair and reasonable costs would be a more effective consumer protection mechanism than the current provisions which place the onus on the client to seek costs assessment, or to have a costs agreement set aside, where they believe they have been overcharged. The National Rules should provide guidance on the meaning of fair and reasonable costs by specifying the factors relevant to determining fairness and reasonableness in the circumstances, and, where appropriate, outlining practices that clearly would breach this obligation. Fairness and reasonableness The courts have recognised the inherent difficulty in determining what is fair and reasonable in relation to legal costs. For example in Veghelyi v Law Society of NSW (unreported, Supreme Court of NSW Court of Appeal, 6 October 1995), Mahoney JA commented that: A solicitor’s entitlement to remuneration is conventionally stated in terms of what is fair and reasonable in the circumstances ... It is, in my opinion, to be recognised that whether costs are fair and reasonable will depend upon—or at least be affected by—facts such as the size of the solicitor’s firm, the resources employed or available to be employed by it, the value which the lawyers place upon their skill and expertise, and the urgency of the clients requirements. What is fair and reasonable for a large firm may be, in the ordinary case, grossly excessive for a sole practitioner. 12 The Taskforce proposes that the National Rules include the same, or similar, criteria for determining fair and reasonable costs as are currently applied by costs assessors. In addition, there are certain practices that generally would indicate that costs are not fair and reasonable for a legal matter, including the following. However, the Taskforce notes that a costs agreement should be considered prima facie evidence that the costs provided in it are fair and reasonable. Multiple charging for the same work The National Rules should prohibit law practices from charging multiple clients for the same work; or, alternatively, provide that the costs for legal services and disbursements undertaken on behalf of multiple clients should be apportioned proportionately between each client (rather than each client bearing the full cost of the work). In Legal Services Commissioner v Bechara [2009] NSWADT 145, the NSW Administrative Decisions Tribunal found a practitioner guilty of professional misconduct for deliberately charging grossly excessive costs under the Legal Profession Act 1987 (NSW). In that case, the practitioner had failed to apportion the costs of a joint hearing involving three clients. Prohibit charging for non legal work The National Rules should prohibit practitioners from charging for communications or administrative activities which are not directly related to the provision of legal advice, including opening files, sending ‘welcome letters’, sending or reading ‘thank you’ and Christmas cards, closing files, reordering an untidy file, the use of a legal practitioner’s trust account, the use of a telephone directory, or charging for contributions to professional indemnity insurance. Administrative costs like file-opening fees are often ‘hidden costs’ which make it harder to compare the value of services offered by competing law practices. They can also increase the costs of accessing the justice system and do not aid the profession’s reputation as they involve significant charges for activities that do not involve the application of professional knowledge, skill or judgement. These costs should be absorbed as overheads by law practices—for example, doctors and dentists do not charge ‘file-opening fees’, they charge for professional services. Taking a call from a client thanking the practitioner for his or her previous service is not a call in which the practitioner is providing a professional service and the client should not be charged for it. Disbursements The Victorian Law Reform Commission has recommended various methods for reducing and rationalising the costs of litigation, including a prohibition on law firms profiting from disbursements (including photocopying), except in the case of clients of reasonably substantial means who agree to pay them. It also recommended that, when a client recovers costs, only the reasonable actual costs of the disbursements (excluding any profit element) should be recoverable from the losing party.24 24 Victorian Law Reform Commission, Civil Justice Review Report (2008). 13 The NSW Legal Fees Review Panel has noted that costs assessors regularly reduce disbursements claimed by practitioners, and that the Costs Assessors’ Rules Committee supported reforms to stop practitioners profiting from in-house disbursements. It recommended that: a practitioner should be required to disclose to a client the existence and nature of any relationship between the practitioner, the practitioner’s firm or any member of the practitioner’s firm and any service provider proposed to be retained to provide services for which the client will be charged; no practitioner, or practitioner’s firm, should be permitted directly or indirectly to make a profit on disbursements; and practitioners should not be permitted to charge separately for disbursements in the nature of overheads (ie, other than payments to independent third parties unrelated to the practitioner or any member of his or her firm).25 The Taskforce proposes that the National Rules include a prohibition on making a profit on disbursements; a prohibition on charging for disbursements that are in the nature of overheads; and a provision that, when a client recovers costs in a matter, only the reasonable actual costs of disbursements should be recoverable. Billing The National Rules should include the following matters, which are largely based on the existing Model Bill provisions. A bill may be in the form of a lump sum bill or an itemised bill (however, if a client requests an itemised bill it must be provided at no cost to the client). A law practice must not commence legal proceedings to recover legal costs from a person until a specified period after the law practice has provided a bill that complies with the National Law and National Rules (subject to reasonable exceptions). A bill must include a written statement setting out the avenues for a client to dispute the legal costs, and any time limits that apply. Additional proposals The National Rules could also include provisions to deal with the following matters. Bills to be signed by principals The Taskforce has recommended new legislative principle that principals of law practices are responsible for the reasonableness of bills rendered to clients, and will be personally liable in theevent of the charging of excessive legal costs in matters in which they have acted or which they have supervised. In addition, a law practice may be liable for the charging of excessive legal costs by one of its principals or one of its employees. To make it clear to principals how they may manage this responsibility, the Taskforce proposes that the National Rules should provide that: (a) a bill must be signed on behalf of a law practice by a principal of the law practice (rather than a legal practitioner or other employee); and (b) once signed, the principal is deemed responsible for the reasonableness of the bill unless the principal establishes that it was not reasonable for him or her to suspect or believe that the bill was excessive in the circumstances. The objective of this proposal is to ensure that principals who sign bills to clients of the law practice make reasonable enquiries as to the content of the bill and its appropriateness in the circumstances. 25 NSW Legal Fees Review Panel, Report: Legal Costs in NSW (2005). 14 In addition, the Taskforce proposes the creation of an offence for a law practice that charges excessive costs in a legal matter without reasonable excuse (eg, where the client is a sophisticated client who has agreed to pay higher legal costs). As a result, a law practice could be fined for charging excessive legal costs, and its principals could be subject to disciplinary proceedings or other penalties imposed under the regime. Interest on late bills Under the Model Bill, a law practice generally may charge interest on unpaid legal costs if the costs are unpaid 30 days or more after the practice has given a complying bill. A law practice may also charge interest on unpaid legal costs in accordance with a costs agreement. The Taskforce is aware that some law practices have rendered bills for work as long as five years after the work has been done. These bills may be issued for various reasons, including where an outside party such as an accountant has been engaged to call in the debts owed to a practice. It has been suggested that ‘this can cause enormous distress and disruption for people who have organised their lives and their finances on the basis that outstanding liabilities had been dealt with’.26 The NSW Legal Fees Review Panel commented that ‘there is no justification in permitting such distress, or benefit in encouraging the continuation of poor administrative and management practices in law firms’. It recommended a prohibition on interest being charged on accounts rendered more than six months after completion of a matter.27 The Taskforce considers that this would be a useful mechanism for ensuring that bills are given to clients within a reasonable period of a matter being finalised, and proposes that this be included in the National Rules. Periodic billing In personal injuries cases (particularly ‘no win no fee’ matters), the absence of bills or regular costs updates can lead to unrealistic client expectations about the amount of the final award or settlement that will be theirs to keep. Irregular bills also contribute to clients losing sight of their expenditure and to them being subsequently surprised by the amount of their accumulated debts. The Model Bill already provides that clients should be provided with updated estimates of costs when there is a significant change to the disclosures previously made. However, it not entirely clear how this requirement operates where no costs are immediately payable (and may not be payable) because the matter is a ‘no win no fee’ agreement. For the sake of clarity and transparency, several members of the NSW Legal Fees Review Panel felt that clients should be apprised of their potential liability at least quarterly. The Taskforce proposes that the National Rules should include an overriding requirement that bills must be sent no less than quarterly. In matters where it has been agreed that a bill will not be issued until completion, the law practice should be required to issue a statement of accrued costs and disbursements at least quarterly. The Taskforce notes the SCAG proposal that all bills rendered in personal injury matters must be itemised, and seeks the views of the Consultative Group and stakeholders on this matter. 26 27 NSW Legal Fees Review Panel, Report: Legal Costs in NSW (2005). NSW Legal Fees Review Panel, Report: Legal Costs in NSW (2005). 15 Recovery of costs The National Rules should include the following matters, which are based on the existing Model Bill provisions. A law practice may take reasonable security from a client for legal costs (including security for the payment of interest on unpaid legal costs); and Legal costs are recoverable: under a valid costs agreement; if this does not apply, in accordance with any applicable costs determination or scale of costs; or if neither of these apply, according to the fair and reasonable value of the legal services provided. Costs assessment There are significant variations across jurisdictions in how costs assessments are undertaken. This can lead to different approaches in allowing costs on assessment and different interpretations about whether costs agreements are reasonable. The Taskforce considers that there is merit in providing a uniform national framework for dealing with disputes over costs quickly and efficiently. As discussed in the paper on the National Legal Services Ombudsman, the Taskforce is proposing that the Ombudsman be able to deal with complaints about legal costs up to $100,000; and, as is currently the case, the charging of excessive costs in a legal matter could result in disciplinary proceedings. In addition, the National Rules would provide for costs assessment by making uniform provision for the following: The timing of applications; Jurisdiction to hear these matters (ie, courts, tribunals, costs assessors etc); The skills and qualifications of costs assessors; The criteria for determining the reasonableness of legal costs; The criteria for setting aside costs agreements; The avenues of appeal; The obligations on the assessor to refer excessive overcharging, and failure to comply with mandatory costs disclosure requirements, to the National Legal Services Ombudsman. The National Rules should provide that, in conducting an assessment of legal costs, the costs assessor must consider: Whether or not it was reasonable to carry out the work to which the legal costs relate; Whether or not the work was carried out in a reasonable manner; and The fairness and reasonableness of the amount of legal costs in relation to the work. In considering what is a fair and reasonable amount of legal costs, the costs assessor may have regard to any or all of the matters already outlined in the Model Bill (and discussed above). If the costs assessor considers that the legal costs charged by a law practice are grossly excessive, the costs assessor must refer the matter to the National Legal Services Ombudsman to consider whether disciplinary action should be taken against a legal practitioner. The costs assessor also may refer any other matter that he or she considers may amount to unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct. There should be a review mechanism from decisions of cost assessors. Consistent with the legislative principles for costs, a costs assessor should also consider proportionality when considering what is a fair and reasonable amount of legal costs. 16 Court management of costs The Taskforce is also considering the issue of court management of costs more generally. This may be the subject of future consultation. 17 ATTACHMENT A Sample costs disclosure in table format. Basis upon Practitioner to circle applicable method of calculating costs: which we will 1. We will charge our costs according to the time spent working on your charge our costs matter, as set out in our covering letter. OR 2. We will charge our costs according to an agreed value for each piece of work as set out in our covering letter. OR 3. We will charge our costs according to the legal budget set out in our covering letter, which provides for payment upon us achieving agreed milestones in your matter. OR 3. We will charge our costs partly based on the time spent working on your matter and partly according to an agreed value for particular pieces of work specified in our covering letter. Estimate of our We advise that the total costs in your matter will be $_______. costs in your OR matter Our costs in this matter are likely to range from $____ to $____, depending on a number of considerations impacting on your matter. The variables that are likely to impact on the costs in your matter are discussed in more detail in our covering letter. Disbursements payable in addition to our legal fees Practitioner to strike out disbursements that will not be charged. You will be required to pay for the costs of the following costs in addition to our legal fees: Photocopying Expert reports Transcription services Courier and other postage costs Faxes Other disbursements as specified in our covering letter. The rate at which each of these disbursements will be charged is set out in our covering letter. The legislation prevents us from profiting from the charges from these disbursements, although we are permitted to charge you a reasonable fee for the labour component associated with obtaining or providing these services. Important note If your case is successful, you may be able to recover costs from the other about costs in party/parties. However, you should be aware that it is unlikely that you litigation. will be able to recover the full amount of your legal costs and you may have to pay some costs to us out of your own pocket. This means that if you are successful, some of the damages you receive will need to be used to pay our costs. If your case is unsuccessful you may have to pay your own legal costs owed to us as well as costs incurred by the other party. 18