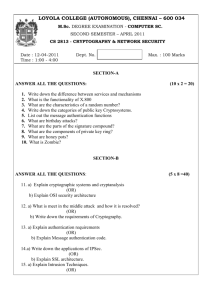

Discussion Paper on Identity Authentication and Authorization in

advertisement