Confidential 31/07/2002 - Jerusalem Center For Public Affairs

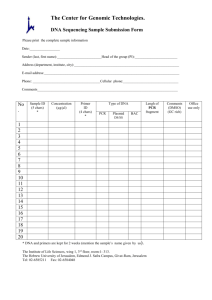

advertisement