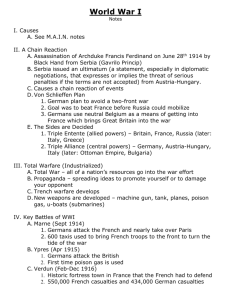

Vypracovala: Hortenská Pavlína Mikešová Zdenka The Origins of

advertisement

Vypracovala: Hortenská Pavlína

Mikešová Zdenka

The Origins of World War One

Early signs in Europe

Under Kaiser Wilhelm II, Germany moved from a policy of maintaining the status quo to a more

aggressive stance. He decided against renewing a treaty with Russia, effectively opting for the

Austrian alliance. Germany's western and eastern neighbours, France and Russia, signed an alliance

in 1894 united by fear and resentment of Berlin. In 1898, Germany began to build up its navy,

although this could only alarm the world's most powerful maritime nation, Britain. Recognising a major

threat to her security, Britain abandoned the policy of holding aloof from entanglements with

continental powers. Within ten years, Britain had concluded agreements, albeit limited, with her two

major colonial rivals, France and Russia. Europe was divided into two armed camps: the Entente

Powers (France, Russia, Great Britain) and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria, Italy), and their

populations began to see war not merely as inevitable but even welcome.

In the summer of 1914 the Germans were prepared, at the very least, to run the risk of causing a

large-scale war. The crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empire decided, after the assassination on 28 June,

to take action against Serbia, which was suspected of being behind the murder. The German

government issued the so-called 'blank cheque' on 5-6 July, offering unconditional support to the

Austrians, despite the risk of war with Russia. Germany, painted into a diplomatic corner by Wilhelm's

bellicosity, saw this as a way of breaking up the Entente, for France and Britain might refuse to

support Russia. Moreover, a wish to unite the nation behind the government may have been a motive.

So might desire to strike against Russia before it had finished rebuilding its military strength after its

defeat by Japan in 1905.

On 28th June 1914, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was

assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia. One month later Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. This was

rapidly followed by other declarations of war, as the system of alliances which had formed in an effort

to maintain the balance of power in Europe followed its inevitable course.

Germany's decision to invade France through neutral Belgium led to the British declaration of war on

Germany on the 4 August. The 'Great War' which developed between the allied powers (led by

France, Russia, Britain and, from 1917, the United States) and the Central Powers (led by Germany

and Austria-Hungary) lasted until 1918. On the western front, the two sides rapidly became

entrenched, and the technology of warfare at the time made it difficult to overcome the ensuing

stalemate.

Although a variety of strategies were employed, including poison gas from 1915 and tanks from 1916,

World War One was remarkable for the extraordinary loss of life in these trenches.

Because of the importance of the European empires at this time, the war was fought on a global level.

Ultimately, however, the loss of life and costs of supplying troops made this a war of attrition. This

became evident in 1917, when the Russian Empire collapsed in revolution. Morale was also collapsing

among the people of Germany.

Although the German army was not defeated in the west, the Central Powers surrendered, signing an

armistice on 11 November 1918. In June 1919 the Treaty of Versailles was signed with Germany. Its

harsh terms, insisted upon by the French and Lloyd George, would prove to be the source of

enormous bitterness in Germany after the war. An estimated 10,000,000 lives had been lost, of which

some 750,000 were British. Twice that number were wounded.

Important people

Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig (1861 - 1928)

2

Douglas Haig

'Kill more Germans' summarised Haig's strategy as Commander in chief of the British forces in France

during most of World War One. His war of attrition resulted in enormous numbers of British casualties

and his leadership remains controversial.

As a young officer, Haig fought in the Sudan, in the Boer War and held administrative posts in India.

From 1906-1909 he was assigned to the War Office, where he helped form the Territorial Army and

organize an expeditionary force for any future war in Europe. When war broke out in August 1914,

Haig led the 1st Corps to northern France. In early 1915 he became commander of the 1st Army

before succeeding Sir John French as commander in chief of the British Expeditionary Force in

December.

In 1916 Haig was responsible for the Battle of the Somme, which cost 420,000 British casualties over

four months for minimal gain. The next year saw further stalemate: the US entered the war in April but

the French command wanted to stay on the defensive until the first of the Americans arrived. This

frustrated Haig, who was subordinate to the French general Robert Nivelle. From May he was given

more authority and determined to defeat the Germans with a purely British offensive. The resulting

Third Battle of Ypres from July to November 1917 (also called Passchendaele) saw further enormous

British casualties that shocked the public back home. Passchendaele failed to reach Haig's objective the Belgian coast - but nonetheless succeeded in weakening the Germans and helped prepare the

way for their defeat in 1918.

Haig remained in his post and from March 1918 succeeded in stopping the last German offensive of

the war (March-July 1918), before showing perhaps his best leadership in the victorious Allied assault

from August onwards.

The early experiences of actual fighting were almost disastrous as the British Expeditionary Force,

cobbled together in much haste and dispatched to Flanders and France, met with severe reverse at

Ypres, and had to retreat from Mons, in disarray and suffering heavy losses. Reduced to only three

corps in strenght, its fighting force was diminished almost from the start.

After the initial disasters, however, the nation and its leaders settled down for a long war. Vital

domestic issues such as Irish home rule were suspended for the duration of hostilities.

The one element required to make it acceptable to a liberal society was some kind of broad, humane

justification to explain what the war was really about. This was provided by Lloyd George, once a bitter

opponent of the Boer War in South Africa in 1899 and for many years member of the Liberal

government. He committed himself without reserve to a fight to the finish.

He declared, it was a war on behalf of liberal principles, a crusade on behalf of the „little five-foot-five

nations, flagrantly invaded by the Germans, or Serbia and Montenegro, now threatened by AustriaHungary.

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd George of Dwyfor (1863 - 1945)

3

David Lloyd George

In the early years of World War One, Lloyd George remained Chancellor of the Exchequer but in 1915

was appointed Minister of Munitions and in 1916, Minister of War. By December 1916, in collaboration

with the Conservatives, Lloyd George became prime minister in place of Asquith. The alliance was to

have fateful consequences for Ireland and for the Liberal Party but first Lloyd George experienced

some of his finest hours as wartime leader of Britain, including the unification of the Allied military

command under the French Marshal Ferdinand Foch.

At the successful conclusion of the war, Lloyd George was Britain's chief delegate to the Paris Peace

Conference that drafted the Versailles Treaty.

Lloyd George remained in Parliament almost to the end of his life. In 1936 he left a blot on his record

of achievements by announcing that he was impressed by Adolf Hitler's achievements in Nazi

Germany - a position that he reversed completely in the late 1930s. Just before his death in 1945 he

was named lst Earl Lloyd George of Dwyfor.

Herbert Asquith (1852 - 1928)

Herbert Asquith

Liberal prime minister of Great Britain from 1908 to 1916, Asquith was responsible for the Parliament

Act of 1911 limiting the power of the House of Lords and led Britain during the first two years of World

War One.

Early in April 1908 Campbell-Bannerman resigned, dying only days later, and Asquith became prime

minister. His chief domestic problem was the opposition of the House of Lords to Liberal reforms;

abroad there was a growing naval competition with Germany. However, the Lords vetoed Lloyd

George's budget of 1909 which would have increased naval expenditure.

4

At war from August 1914, Asquith formed a coalition government the following May, admitting

Unionists as well as Liberals. However, in 1915 the Dardanelles expedition failed and there was no

sign of any breakthrough on the Western Front. 1916 was even worse with the Easter Rising in Dublin,

the Battle of the Somme and the consequent massive casualties. The long-awaited introduction of

conscription was insufficient to quell dissent and Asquith was under constant media attack. In

December he resigned and was replaced by Lloyd George.

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (1869 - 1940)

Arthur Neville Chamberlain

Chamberlain, the man who made 'appeasement' famous, was from a family of statesmen. His father,

Joseph, had been leader of both the Liberal Unionist party and then a colonial secretary in the

Conservative government.

During World War One he supervised national conscription in Lloyd George's government, but when it

became clear his job didn't offer the power he needed, he resigned. One year later, he was elected to

parliament as a Conservative MP.

The British Army in World War One

Techniques and strategies

In 1914-17 the defensive had a temporary dominance over the offensive. A combination of 'high tech'

weapons (quick-firing artillery and machine guns) and 'low tech' defences (trenches and barbed wire)

made the attacker's job formidably difficult. Communications were poor. Armies were too big and

dispersed to be commanded by a general in person, as Wellington had at Waterloo a century before,

and radio was in its infancy. Even if the infantry and artillery did manage to punch a hole in the enemy

position, generals lacked a fast-moving force to exploit the situation, to get among the enemy and turn

a retreat into a rout.

In previous wars, horsed cavalry had performed such a role, but cavalry were generally of little use in

the trenches of the Western Front. In World War Two, armoured vehicles were used for this purpose.

With commanders mute and an instrument of exploitation lacking, World War One generals were

faced with a tactical dilemma unique in military history.

Breakthrough battle

The problem was that in 1914 tactics had yet to catch up with the range and effectiveness of modern

artillery and machine guns. Warfare still looked back to the age of Napoleon. By 1918, much had

changed. At the Battle of Amiens on 8 August 1918, the BEF put into practice the lessons learned, so

painfully and at such a heavy cost, over the previous four years. In a surprise attack, massed artillery

5

opened up in a brief but devastating bombardment, targeting German gun batteries and other key

positions. The accuracy of the shelling, and the fact that the guns had not had to give the game away

by firing some preliminary shots to test the range, was testimony to the startling advances in technique

which had turned gunnery from a rule of thumb affair into a highly scientific business.

Then, behind a 'creeping barrage' of shells, perfected since its introduction in late 1915, British,

French, Canadian and Australian infantry advanced in support of 552 tanks. The tank was a British

invention which had made its debut on the Somme in September 1916. Overhead flew the aeroplanes

of the Royal Air Force, created in April 1918 from the old Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air

Service. The aeroplane had come a long way from its 1914 incarnation as an extremely primitive

assemblage of struts and canvas, its task confined to reconnaissance.

By Amiens, aeroplanes were considerably more sophisticated than their predecessors of 1914. The

RAF carried out virtually every role fulfilled by modern aircraft: ground attack, artillery spotting,

interdiction of enemy lines of communication, strategic bombing. This air-land 'weapons system' was

bound together by wireless (radio) communications. These were primitive, but still a significant

advance on those available two years earlier on the Somme.

Military revolution

The German defenders at Amiens had no response to the Allied onslaught. By the end of the battle,

the attackers had advanced 13km (eight miles) - a phenomenal distance by Great War standards. The

Germans lost 27,000 men, including 15,000 prisoners and 400 guns. It was, the German commander

Ludendorff admitted, the 'Black Day of the German Army'. From this point onward, the result of the war

was never in doubt. Amiens demonstrated the extent of the military revolution that occurred on the

Western Front between 1914 and 1918. It was a modern battle, the prototype of combats familiar to

armies of our own times.

One cannot ignore the appalling waste of human life in World War One. Some of these losses were

undoubtedly caused by incompetence. Many more were the result of decisions made by men who,

although not incompetent, were like any other human being prone to making mistakes. Haig's decision

to continue with the fighting at Passchendaele in 1917 after the opportunity for real gains had passed

comes into this category. In some ways the British and other armies might have grasped the potential

of technology earlier than they did. During the Somme, Haig and Rawlinson failed to understand the

best way of using artillery.

Haig, however, was no technophobe. He encouraged the development of advanced weaponry such as

tanks, machine guns and aircraft. He, like Rawlinson and a host of other commanders at all levels in

the BEF, learned from experience. The result was that by 1918 the British army was second to none in

its modernity and military ability. It was led by men who, if not military geniuses, were at least

thoroughly competent commanders. The victory in 1918 was the payoff. The 'lions led by donkeys' tag

should be dismissed for what it is - a misleading caricature.

Battles

Battle of Tannenberg: 26-30 August 1914

Two Russian armies invaded German East Prussia in August 1914. Rennenkampf's First Army was to

converge with the Samsonov's Second Army to give a two-to-one numerical superiority over the

German 8th Army, which they would attack from the east and south respectively, some 80km (50

miles) apart.

The plan began well at Gumbinnen on 20 August, when Rennenkampf's First Army defeated eight

divisions of the German 8th Army on its eastern front. By this time Samsonov's forces had crossed the

southern frontier of East Prussia to threaten the German rear, defended by only three divisions.

Faced with imminent attack, Prittwitz, commander of the 8th Army, approved Lieutenant Colonel

Hoffman's idea to attack Samsonov's left flank, aided by another three divisions moved by rail from the

6

Gumbinnen front. However, on 23 August Prittwitz was replaced by General von Hindenburg whose

chief of staff, Ludendorff, immediately confirmed Hoffmann's plan to strike at Samsonov's left flank.

The Germans then got lucky when they intercepted an uncoded Russian message indicating that

Rennenkampf was in no hurry to advance. Developing Hoffman's original plan, Ludendorff

concentrated six divisions against Samsonov's left flank and took a calculated risk to withdraw the rest

of the German troops from Gumbinnen and move them to face Samsonov's right flank, leaving only a

cavalry screen against Rennenkampf. This move was helped by the lack of communication between

the two Russian commanders, who disliked each other.

Samsonov's forces were spread out along a 60 mile front and advancing gradually against the

Germans when, on 26 August, Ludendorff ordered an attack on Samsonov's left wing near Usdau.

There, German artillery forced a Russian retreat, whereupon they were pursued toward Neidenburg, in

the rear of the Russian centre.

A Russian counter-attack from Soldau enabled two Russian army corps to escape south east before

the German pursuit continued. By nightfall on 29 August the Russian centre, amounting to three army

corps, was surrounded by Germans and stuck in a forest with no means of escape. The Russians

disintegrated and were taken prisoner by the thousands. Faced with total defeat, Samsonov shot

himself. By the end of the month, the Germans had taken 92,000 prisoners and annihilated half of the

Russian 2nd Army. Rennenkampf's army had not moved at all during this battle, vindicating

Ludendorff's calculated risk.

After being reinforced, the Germans turned on Rennenkampf's slowly advancing Army, attacking it in

the first half of September and driving it from East Prussia. It was a crushing defeat for the Russians.

In total, they lost around 250,000 men - an entire army - as well as vast amounts of military equipment.

The wafer-thin silver lining was that the Russian action had diverted the Germans from their attack on

France and allowed the French to counter-attack at the Marne.

Battle of the Marne: 6-10 September 1914

The First Battle of the Marne marked the end of the German sweep into France and the beginning of

the trench warfare that was to characterise World War One.

Germany's grand Schlieffen Plan to conquer France entailed a wheeling movement of the northern

wing of its armies through central Belgium to enter France near Lille. It would turn west near the

English Channel and then south to cut off the French retreat. If the plan succeeded, Germany's armies

would simultaneously encircle the French Army from the north and capture Paris.

A French offensive in Lorraine prompted German counter-attacks that threw the French back onto a

fortified barrier. Their defence strengthened, they could send troops to reinforce their left flank - a

redistribution of strength that would prove vital in the Battle of the Marne. The German northern wing

was weakened further by the removal of 11 divisions to fight in Belgium and East Prussia. The

German 1st Army, under Kluck, then swung north of Paris, rather than south west, as intended. This

required them to pass into the valley of the River Marne across the Paris defences, exposing them to a

flank attack and a possible counter-envelopment.

On 3 September, Joffre ordered a halt to the French retreat and three days later his reinforced left

flank began a general offensive. Kluck was forced to halt his advance prematurely in order to support

his flank: he was still no further up the Marne Valley than Meaux.

On 9 September Bülow learned that the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was advancing into the gap

between his 2nd Army and Kluck. He ordered a retreat, obliging Kluck to do the same. The

counterattack of the French 5th and 6th Armies and the BEF developed into the First Battle of the

Marne, a general counter-attack by the French Army. By 11 September the Germans were in full

retreat.

7

This remarkable change in fortunes was caused partially by the exhaustion of many of the German

forces: some had marched more than 240km (150 miles), fighting frequently. The German advance

was also hampered by demolished bridges and railways, constricting their supply lines, and they had

underestimated the resilience of the French.

The Germans withdrew northward from the Marne and made a firm defensive stand along the Lower

Aisne River. Here the benefits of defence over attack became clear as the Germans repelled

successive Allied attacks from the shelter of trenches: the First Battle of the Aisne marked the real

beginning of trench warfare on the Western Front.

In saving Paris from capture by pushing the Germans back some 72km (45 miles), the First Battle of

the Marne was a great strategic victory, as it enabled the French to continue the war. However, the

Germans succeeded in capturing a large part of the industrial north east of France, a serious blow.

Furthermore, the rest of 1914 bred the geographic and tactical deadlock that would take another three

years and countless lives to break.

Battle for Gallipoli: February 1915 - January 1916

By 1915 the Western Front was clearly deadlocked. Allied strategy was under scrutiny, with strong

arguments mounted for an offensive through the Balkans or even a landing on Germany's Baltic coast,

instead of more costly attacks in France and Belgium.

These ideas were initially sidelined, but in early 1915 the Russians found themselves threatened by

the Turks in the Caucasus and appealed for some relief. The British decided to mount a naval

expedition to bombard and take the Gallipoli Peninsula on the western shore of the Dardanelles, with

Constantinople as its objective. By capturing Constantinople, the British hoped to link up with the

Russians, knock Turkey out of the war and possibly persuade the Balkan states to join the Allies.

The naval attack began on 19 February. Bad weather caused delays and the attack was abandoned

after three battleships had been sunk and three others damaged. Military assistance was required, but

by the time troops began to land on 25 April, the Turks had had ample time to prepare adequate

fortifications and the defending armies were now six times larger than when the campaign began.

Against determined opposition, Australian and New Zealand troops won a bridgehead at 'Anzac Cove'

on the Aegean side of the peninsula. The British, meanwhile, tried to land at five points around Cape

Helles, but established footholds in only three before asking for reinforcements. Thereafter little

progress was made, and the Turks took advantage of the British halt to bring as many troops as

possible onto the peninsula.

This standstill led to a political crisis in London between Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty and

the operation's chief advocate, and Lord Fisher, the First Sea Lord, who had always expressed doubts

about it. Fisher demanded that the operation be discontinued and resigned when overruled. The

Liberal government was replaced by a coalition and Churchill, though relieved of his former post,

remained in the War Council.

Amid sweltering and disease-ridden conditions, the deadlock dragged on into the summer. In July the

British reinforced the bridgehead at Anzac Cove and in early August landed more troops at Suvla Bay

further to the north, to seize the Sari Bair heights and cut Turkish communications. The offensive and

the landings both proved ineffectual within days, faced with waves of costly counter-attacks.

The War Council remained divided until late 1915 when it was decided to end the campaign. Troops

were evacuated in December 1915 and January 1916. Had Gallipoli succeeded, it could have ended

Turkey's participation in the war. As it was, the Turks lost some 300,000 men and the Allies around

214,000, achieving only the diversion of Turkish forces from the Russians. Bad leadership, planning

and luck, combined with a shortage of shells and inadequate equipment, condemned the Allies to

seek a conclusion in the bloody battles of the Western Front. Furthermore, Gallipoli's very public

failure contributed to Asquith's replacement as Prime Minister by David Lloyd George in December

1916.

8

Battle of Verdun: 21 February 1916 - July 1916

One of the costliest battles of World War One, Verdun exemplified the 'war of attrition' pursued by both

sides and which cost so many lives.

By the winter of 1915-16, German General Erich von Falkenhayn was convinced that the war could

only be won in the west. He decided on a massive attack on a French position 'for the retention of

which the French Command would be compelled to throw in every man they have'. Once the French

army had bled to death, Britain would be fighting alone on the Western Front and could be brought

down by Germany's submarine blockade.

Falkenhayn targeted the town of Verdun and its surrounding forts. They threatened German lines of

communication and lay within a French salient (a bulge in the line), restricting their defenders. Verdun

was a Gallic fortress before Roman times and later a key asset in wars against Prussia, and

Falkenhayn knew that the French would throw as many men as necessary into its defence. He

realised that this would enable him to inflict the maximum possible casualties.

He massed artillery to the north and east of Verdun to pre-empt the infantry advance with intensive

artillery bombardment. Although French intelligence had warned of his plans, these warnings were

ignored by the French Command. Consequently, Verdun was utterly unprepared for the initial

bombardment on the morning of 21 February 1916. German infantry attacks followed that afternoon

and met little resistance for the first four days.

On 25 February the Germans occupied Fort Douaumont. French reinforcements arrived and, under

the leadership of General Pétain, they managed to slow the German advance with a series of counterattacks. Over March and April the hills and ridges north of Verdun exchanged hands, always under

heavy bombardment. Meanwhile, Pétain organised repeated counter-attacks to slow the German

advance. He also ensured that the Bar-le-Duc road into Verdun - the only one to survive German

shelling - remained open. It became known as La Voie Sacrée ('the Sacred Way') because it

continued to carry vital supplies and reinforcements into the Verdun front despite constant artillery

attack.

German gains continued in June, but slowly. They attacked the heights along the Meuse and took Fort

Vaux on 7 June. On 23 June they almost reached the Belleville heights, the last stronghold before

Verdun itself. Pétain was preparing to evacuate the east bank of the Meuse when the Allies' offensive

on the Somme River was launched on 1 July, partly to relieve the French. The Germans could no

longer afford to commit new troops to Verdun and, at a cost of some 400,000 French casualties and a

similar number of Germans, the attack was called off. Germany had failed to bleed France to death

and from October to the end of the year, French offensives regained the forts and territory they had

lost earlier. Falkenhayn was replaced by Hindenburg as Chief of General Staff and Pétain became a

hero, eventually replacing General Nivelle as French commander-in-chief.

Battle of the Somme: 1 July - 13 November 1916

Intended to be a decisive breakthrough, the Battle of the Somme instead became a byword for futile

and indiscriminate slaughter, with General Haig's tactics remaining controversial even today.

The British planned to attack on a 24km (15 mile) front between Serre, north of the Ancre, and Curlu,

north of the Somme. Five French divisions would attack an 13km (eight mile) front south of the

Somme, between Curlu and Peronne. To ensure a rapid advance, Allied artillery pounded German

lines for a week before the attack, firing 1.6 million shells. British commanders were so confident they

ordered their troops to walk slowly towards the German lines. Once they had been seized, cavalry

units would pour through to pursue the fleeing Germans.

However, unconcealed preparations for the assault and the week-long bombardment gave the

Germans clear warning. Happy to remain on French soil, German trenches were heavily fortified and,

furthermore, many of the British shells failed to explode. When the bombardment began, the Germans

9

simply moved underground and waited. Around 7.30am on 1 July, whistles blew to signal the start of

the attack. With the shelling over, the Germans left their bunkers and set up their positions.

As the 11 British divisions walked towards the German lines, the machine guns started and the

slaughter began. Although a few units managed to reach German trenches, they could not exploit their

gains and were driven back. By the end of the day, the British had suffered 60,000 casualties, of

whom 20,000 were dead: their largest single loss. Sixty per cent of all officers involved on the first day

were killed.

It was a baptism of fire for Britain's new volunteer armies. Many 'Pals' Battalions, comprising men from

the same town, had enlisted together to serve together. They suffered catastrophic losses: whole units

died together and for weeks after the initial assault, local newspapers would be filled with lists of dead,

wounded and missing.

The French advance was considerably more successful. They had more guns and faced weaker

defences, yet were unable to exploit their gains without British backup and had to fall back to earlier

positions.

With the 'decisive breakthrough' now a decisive failure, Haig accepted that advances would be more

limited and concentrated on the southern sector. The British took the German positions there on 14

July, but once more could not follow through. The next two months saw bloody stalemate, with the

Allies gaining little ground. On 15 September Haig renewed the offensive, using tanks for the first time.

However, lightly armed, small in number and often subject to mechanical failure, they made little

impact.

Torrential rains in October turned the battlegrounds into a muddy quagmire and in mid-November the

battle ended, with the Allies having advanced only 8km (five miles). The British suffered around

420,000 casualties, the French 195,000 and the Germans around 650,000. Only in the sense of

relieving the French at Verdun can the British have claimed any measure of success.

Battle of Passchendaele: 31 July - 6 November 1917

Officially known as the Third Battle of Ypres, Passchendaele became infamous not only for the scale

of casualties, but also for the mud.

Ypres was the principal town within a salient (or bulge) in the British lines and the site of two previous

battles: First Ypres (October-November 1914) and Second Ypres (April-May 1915). Haig had long

wanted a British offensive in Flanders and, following a warning that the German blockade would soon

cripple the British war effort, wanted to reach the Belgian coast to destroy the German submarine

bases there. On top of this, the possibility of a Russian withdrawal from the war threatened German

redeployment from the Eastern front to increase their reserve strength dramatically.

The British were further encouraged by the success of the attack on Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917.

Nineteen huge mines were exploded simultaneously after they had been placed at the end of long

tunnels under the German front lines. The capture of the ridge inflated Haig's confidence and

preparations began. Yet the flatness of the plain made stealth impossible: as with the Somme, the

Germans knew an attack was imminent and the initial bombardment served as final warning. It lasted

two weeks, with 4.5 million shells fired from 3,000 guns, but again failed to destroy the heavily fortified

German positions.

The infantry attack began on 31 July. Constant shelling had churned the clay soil and smashed the

drainage systems. The left wing of the attack achieved its objectives but the right wing failed

completely. Within a few days, the heaviest rain for 30 years had turned the soil into a quagmire,

producing thick mud that clogged up rifles and immobilised tanks. It eventually became so deep that

men and horses drowned in it.

On 16 August the attack was resumed, to little effect. Stalemate reigned for another month until an

improvement in the weather prompted another attack on 20 September. The Battle of Menin Road

10

Ridge, along with the Battle of Polygon Wood on 26 September and the Battle of Broodseinde on 4

October, established British possession of the ridge east of Ypres.

Further attacks in October failed to make much progress. The eventual capture of what little remained

of Passchendaele village by British and Canadian forces on 6 November finally gave Haig an excuse

to call off the offensive and claim success.

WWI: 750,000 British and 250,000 Commonwealth soldiers killed, mainly on the French and Belgian

battlefields, 3 million people wounded

40% of the commercial fleet was sunk

Remembrance Day 11.11. at 11 o´clock – 2 minutes of silence are preserved all over the country – it is

exact time when the peace treaty was signed

This custom also comemorates the people killed in WWII

11