Assessment of Caloric and Protein Intake in Sudan

advertisement

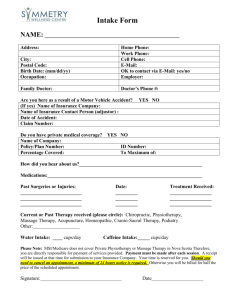

NAF International Working Paper Series Year 2014 paper n. 14/4 Assessment of Caloric and Protein Intake in Sudan Samar Abdalla Agricultral Research Corporation (ARC) Agricultural Economics and Policy Research Centre (AEPRC) Khartoum North, Shambat, Sudan The online version of this article can be found at: http://economia.unipv.it/naf/ 1 Scientific Board Maria Sassi (Editor) - University of Pavia Johann Kirsten (Co-editor)- University of Pretoria Gero Carletto - The World Bank Piero Conforti - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Marco Cavalcante - United Nations World Food Programme Luc de Haese - Gent University Stefano Farolfi - Cirad - Joint Research Unit G-Eau University of Pretoria Ilaria Firmian -IFAD Mohamed Babekir Elgali – University of Gezira Luca Mantovan – Dire Dawa University Firmino G. Mucavele - Universidade Eduardo Mondlane Michele Nardella - International Cocoa Organization Nick Vink - University of Stellenbosch Alessandro Zanotta - Delegation of the European Commission to Zambia Copyright @ Sassi Maria ed. Pavia -IT naf@eco.unipv.it ISBN 978-88-96189-20-7 2 Assessment of Caloric and Protein Intake in Sudan Samar Abdalla1 Agricultral Research Corporation (ARC), Agricultural Economics and Policy Research Centre (AEPRC), Khartoum North, Shambat, Sudan Abstract: this paper seeks to evaluate the adequate levels of caloric and protein intake as well as to examine the factors that influencing the adequate levels of caloric and protein intake among the rural households in the tradiotional agricultural sector of Sudan. The primary data was collected from 200 rural households using both structured and food recall questionnaires. The actual levels of caloric and protein intake were assessed using food composition tables for Sudan and Africa. The requirement levels of caloric and protein intake were evaluated for all household members using the RDA and AIs presented by Food and Nutrition Board (FNB). Moreover, the determinant factors of the adequate caloric and protein intake were analyzed using binary logistic model. The results show that about 81.5% and 34% of the rural household have the inadequate levels of caloric and protein intake, respectively. The logistic model reveals that an increase in the total household income probably leads to an increase in the adequate level of caloric and protein intake. Household size has a negative impact on the adequate levels of both caloric and protein intake (p<0.01). However, the age of the head of the households has significantly influenced the adequate level protein intake at level p<0.05. The paper recommends to create nutrient reference values for Sudanese people and to launch a major nutrition program to encourage food diversity in the rural areas. Furthermore, supporting the role of female headed households in the rural communities is essentially necessarly to improve the adequate level of caloric and protein intake. Keywords: caloric intake, protein intake, adequate intake, RDA, AIs, logistic regression 1. Introduction The food consumption and nutrient intake differ among the households and individuals, and they depend largely on food preferences, food tests, religion, food availability, and purchasing power of the people in a given community. This means the food consumption pattern preferred by a group of individuals or particular household members may or may not be preferred by the other group. In contrast, there are different factors affecting the adequate nutrient intake by household members, including socioeconomic, environmental, and political factors. There are two types of hunger: undernourishment and malnourishment. Undernourishment describes the situation where the individual’s food intake falls below the minimum calorie (energy) requirement, whereas malnourishment is the situation when the caloric intake is insufficient, and the protein and other essential nutrient intake are also inadequate (FAO, 2001). Indeed, as in many developing countries, the data on food consumption are only available from the international Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). The data on food consumption is developed through the Food Balance Sheet (FBS). The FAO-FBS estimates the amount of per capita food supply, production, imports, and dietary energy consumption from different food items. The FAO provides only the aggregate data (i.e. the total food production or total food supply divided by the total population). These data help in the case of comparison between countries, but it does not present a complete and precise picture on the situation of food and nutrition security among households or individuals within the country. In view of that, the lack of real data on food consumption is one of the main limitations to realize the level of self-sufficiency and food security. This would encourage the entitlement of food consumption and nutrition surveys in order to assess the real level of food consumption and nutrient intake for the households. Sudan has experienced from severe food deficit since the last two decades. The oil production and exports have a positive impact on the economic growth and development. However, 50% to 60% of the population is suffering from poverty and food insecurity with a high variation among the regions (WFP, 2006). This condition is attributed to two specific reasons. The first reason is the drastically declining role of agriculture, which supports the livelihood of 80% of the population. The second reason is that the increase in the economic growth and benefits from oil exports does not trickle down to the poor. In fact, Sudan lost its self-sufficiency in cereal food grains due to serious drought, civil war crises, and inappropriate government policies. Consequently, rural people have 1 Corresponding author: Samar Abdalla, (PhD), Research fields: agricultural economics, food security and farm management. E-mail: samar-122@hotmail.com. 3 suffered from continuous deterioration in their food consumption, which creates a higher food deficit. Thus, such a situation forced the country to rely on food relief from the international communities. The majority of the population in the traditional agricultural sector are occupied with agriculture and related activities. They cultivate food crops (sorghum and millet) and cash crops (sesame, groundnut, hibiscus, and watermelon) in addition to gum Arabic taping and pastoral activities. Recently, this sector has suffered from declining productivity of all crops (Elamin et al., 2009). As a consequence, the rural household is distressed by higher food deficiency due to the low quantities of food produced. This caused a greater reduction in the amount of crop production and income as well. Nowadays, the per capita income from crop production has fallen below the poverty line (Faki et al., 2009). On the other hand, the consumption of cereal foods in the traditional agricultural sector contributes more than 54% to the total daily per capita caloric intake. The consumption of rural people is characterized by low food diversity, which results in a high prevalence of malnutrition and low caloric (energy) intake. The per capita energy intake is below the FAO minimum energy requirements (2,100 kcal). In agreement with this, the average per capita energy intake for the rural people is about 1,663 kcal and for the overall population is about 1,803 kcal which is very low (Hashim, 2008). Such a situation causes widespread diseases, malnutrition, and poor sanitary conditions. Subsequently, this situation leads to unavailability of food, inaccessibility to enough food and/or bad quality of food intake. Therefore, this paper seeks to evaluate the level of household food consumption, the adequate level of caloric and protein intake as well as to examine the determinant factors that influencing the adequate level of caloric and protein intake among the rural households. 2. Research Methodology Study area and Sampling North Kordofan State is located in the traditional agricultural sector particularly in the Central Western part of Sudan between latitudes 12°15′ -16° 32′ North and longitudes 27°-32° East. According to the administrative governmental system in Sudan; the new North Kordofan State is composed of nine localities: Sheikan, Bara, UmRuwaba, Gabrat El Sheikh, Sodari, El Nuhoud, Gebash, Wad Banda, and Abu Zabad, of which four of them were merged from the former West Kordofan State. The total number of localities consists of approximately 33 administrative units (MFEP, 2008). The rural households in this region live together in different structured village communities. However, there is not much variation within the villages or between villages in the same locality as argued by El Bashir (1999) and Elkhidir (2003). This is mostly because the rural households who live in the selected sites seem to be homogeneous and consistent. The rural households also belong to a closely interrelated community, and the same ethnic tribes are governed by the same rules and display similar socioeconomic characteristics. Subsequently, a technique of multi-stage random sampling was used to select the sample of the rural households. Based on the estimation of the total population in the rural area, a random sample of about 200 rural households were selected, which is approximately 6% from the total number of farm households in the study area (the total number of farm households is about 3,209). Data collection The primary data was collected through field surveys using household structured questionnaire and food recall questionnaire. The field survey was conducted during the period of June to October, 2009. The heads of the households were responsible from decision-making for all household members concerning the food consumption. Thus, both questionnaires are largely targeted the head of the households and their members. The sturctured questionnaire comprised the following data and information: the household socioeconomic characteristics and household demographic parameters such as age, household size, education, land size and farming activities. Besides all of this information, collection of other essential data was made over the household income sources (farm and off-farm income). The food recall questionnaire was applied during the time of the field survey simultaneously with the general structured questionnaire. The purpose of the food recall questionnaire is to collect data and information relevant to the quality and quantity of food consumed by the household members during a specific period of time (3 days). The days selected for carrying out the food recall questionnaire were determined previously by the investigator during the time of the field survey. The food recall questionnaire was designed to cover an equivalent number to the selected sample of the farm households (200 samples). The food recall questionnaire was devised to include information on the daily household’s food consumption, sources of food, and daily food expenditure. Accordingly, the farm household was asked to recall and estimate the amount of foods consumed during the past three days. The 4 fundamental justification for this that rural households may change or diversify their food consumption for one day during the time of the survey. Thus, food recall for three days was chosen to capture the change in food consumption in day to day variations in the household food consumption. Moreover, the information on the total food cooked for household consumption and the portion size consumed by the household members was estimated using the standard household measurement. Estimation of caloric and protein intake The most accurate and reliable method used to measure food intake is the weighing method, which was mentioned by Ahmed (1970) and Abuzied et al. (2006). The level of nutrient intake is usually used as an indication of satisfactory food consumption. In this study, the average quantity of different foods consumed by the farm households was estimated using a three-day food recall. The daily food consumption was used to assess the average quantity of caloric and protein intake by the rural farm households during specific period of time. Hypothetically, the calculation of caloric and protein intake can be estimated using the following formula as argued by Iyangbe and orewa (2009): m N ab……………………………………………………….…………………………………… (1) si i 1 ij j Where N si : The daily caloric and protein for ith households, a ij b j : The weight in grams of the average daily food commodity j by i th the households, : The standardized food for each of the caloric and protein content in the jth food commodity. The quantities of various foods consumed by the farm households varied according to the characteristics of the household members (e.g. age and sex). Different age and sex groups had different quantities of food consumption and nutrient intake. As in many developing countries, the estimation of the real food consumption for the individuals is difficult and complex. In Sudan, it is difficult to estimate the actual food consumed for each individual or member within the household, since the household members share their daily food consumption. The amounts of both caloric and protein were calculated based on the daily quantities of food consumed by the household members. The actual levels of caloric and protein intake were estimated using food composition table for Africa (FAO, 1968), food composition table for Sudan (Boutros, 1986). On the other hand, the requirement levels of caloric and protein intake differ among the household members according to their age and sex. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the requirements of caloric and protein intake for each member in the household. For this reason, these requirements were calculated for infants, children, males, and females in different age groups. The requirements of caloric and protein intake for the entire household were based on the recommended levels of both caloric and protein intakes for all individuals or members in the household. These requirements for the whole household can be easily obtained by the sum of the recommended level for all household members. With a different composition of the household (i.e. characteristics of the household members, sex and age groups) there is a different level of requirement or recommendation. Therefore, the recommendation or the requirement level may vary from one household to another. The requirements of caloric and protein intake for the household members were estimated based on the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) and the Adequate Intake (AI) which are presented by the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB). The RDA is the average daily dietary nutrient intake level sufficient to meet the nutrient requirement for nearly all (97-98%) healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group. The AI is the recommended level based on the approximation or estimation of nutrient intake for an age group of apparently healthy people that are assumed to be adequate. The AI is used when the RDA cannot be determined (Jennifer et al., 2006). Table 1 summarizes the RDA and the AI of caloric and protein intake for individuals in different life stages. The RDA is defined as the amount of selected nutrient intake considered to be adequate to meet known nutrient needs for healthy people (FAO, 1994). The RDA and the AI are both used as goals for individuals in different age groups. For healthy, breast-fed infants, the AI is the mean intake. The AIs for the other life stages and gender groups are believed to cover the needs of all individuals in the group (FNB, 2005). 5 Table 1: The RDA and AI of caloric and protein for individuals in different life stages and gender groups Stage group Infant 0-6 mounth 7-12 mounth Children 1-3 year 4-8 year Males 9-13 year 14-18 year 19-30 year 31-50 year 51-70 year >70 year Females 9-13 year 14-18 year 19-30 year 31-50 year 51-70 year >70 year Caloric (Kcal/day) Protein (g/day) 650 850 9.11 11 1,300 1,800 13 19 2,500 3,000 2,900 2,900 2,300 2,300 34 52 56 56 56 56 2,300 2,200 2,200 2,200 1,900 1,900 34 46 46 46 46 46 Remark: 1 the reference intake: Adequate Intakes (AIs) Source: FNB (2005) Caloric and protein intake: model specification In the econometrics modeling approaches, the binary logistic model has been applied under the general probability of non-linear models. In this case the research problems call for the analysis and prediction of a dichotomous and dummy outcome (Chao et al., 2002). The binary logistic regression model intensively uses the dependent variable in the form of a dummy variable (discrete). The logistic regression model is expressed in terms of the probability of Y occurring, which means the probability that the households belong in a certain category (Nyaga and Doppler, 2009). In this case, the binary logistic regression model is used to determine the effects of specific household characteristics and farming factors on the adequate levels of both caloric and protein intake. The binary logistic regression model is broadly used in dietary intake and nutrient intake, using the estimation of the maximum log likelihood method. This method is applied as a predictor for the model, since the relation between the variables is not linear (Bartali et al., 2006, and Maeve et al., 2007). The formulation of the binary logistic regression model shows that the observed response of the dependent variable is represented by the dependent variable (Y). In this situation the dependent variables denote by the levels of caloric and protein intake. The dependent variables are used as observed values (dummy variables). These values are derived from the differences between the actual levels and the required levels of caloric and protein intake (≥ required level=1) and (< required level=0). This is applied for all households and it takes only one of the two possible values (0, 1). The estimation of the quantitative relationship between the adequate levels of caloric and protein intake and the factors influencing these levels was established to predict whether the farm households consume adequate levels of caloric and protein intake or not. This relationship was estimated by using the binary logistic regression models in order to estimate the probability (pi) of the adequate levels of caloric and protein intake, given certain conditions. The following model gives the estimation of the probability of the adequate levels of caloric and protein intake (Pi): x x B B B …..……………………..….(2) 1 e prob 1 p Y x x x x B B B B B B 1 1 e e ( ... ) 0 1 j 1 i ji i i i ( ... ) 0 1 j 1 i ji i 6 ( ... ) 0 1 j 1 i ji i Similarly, the probability that the households consume inadequate levels of caloric and protein intake takes a 0 value if (1-Pi): 1 prob 0 1 Pr ob 1 ……….................................................... (3) Y Y i i ( ... ) x x B B B 0 1 j 1 i ji i 1 e The likelihood of being food and nutritionally secure is given by the odds ratio in support of the consumption of adequate levels of caloric and protein intake by dividing (2) by (3) as follows: p x B B e 1 p ( i 11 ... j i 0 …………..…………..………………..……….…............. (4) ) x B ji i i Taking the normal log in both sides of equation (5) we get: …………………………………………………………………..... (5) p i log .... x x x B B B 0 1 2 j 1 jB 2 j jii 1 p i Pi means the vector of probabilities of the adequate level of nutrient intake, which is measured as the dummy variable and takes a value between 0 and 1. Xi represents the explanatory variables of specific factors including the socioeconomic and farming characteristics of the farm households. Bo is a constant (intercept), Bi is a vector of parameters to be estimated, e is the standard base of the system of natural logarithms (e=2.71828) and ɛi means the stochastic-disturbance term and is estimated to be normal distribution (Greene, 2003). The binary logistic regression model was fitted to obtain the estimates of the odds ratio for each of the coefficients (Exp (bi)), which is pi 1 pi equal to log . The model was estimated using the STATA version 10 computer program. The following empirical models were used to predict the relationship between adequate levels of both caloric and protein intake and the explanatory variables. The specification model of the adequate level of caloric intake: p i prob EI i 1 1 B0 + B1GEND + B2HHIC + B3EDU+ B4HHS + B5AGE+ B6FS + B7OLIV + B8TCSS + B9NCC + i ) ..…………….….......(6) ( 1 e The specification model of the adequate level of protein intake: p i prob PI i 1 ……………..……....(7) 1 B0 + B1GEND + B2HHIC + B3EDU+ B4HHS + B5AGE +B6FS + B7OLIV + B8TCSS + B9NCC + i ) ( 1 e The statistical significance of the individual parameters (odds ratio) was interpreted using the p-value, which is the alternative way to assess the significance of the maximum likelihood estimates. The null hypotheses underlying the overall models states that all Bs equal zero. A rejection of the null hypotheses implies that at least one B does not equal zero for the population, which means that the binary logistic regression equation predicts the probability of the outcome better than the means of the dependent variables (Y). The interpretation of the result was estimated using the odds ratio for both dummy and continuous predictors (Chao et al., 2002). 3. Results and discussion Adequate levels of caloric and protein intake Table 2 presents the average requirements and actual levels of both caloric and protein intake for the farm households in the traditional agricultural sector of North Kordofan State. The results illustrate that the average 7 requirement levels of caloric intake for the farm households is about 13,726 (kcal/day). The average requirement (recommended levels) of protein is about 245.50 (g/day). In contrast, the average actual level of caloric (energy) and protein intake for farm households is equal to 8,801.26 (kcal/day) and 327.09 (g/day) respectively. Furthermore, the findings show a large discrepancy between the recommended and actual levels of both caloric and protein intake. This can be shown by the t-test value of caloric (12.07***) and protein (6.41***). The low quality and quantity of different foods as well as improper food diets are decisive factors that lead to low daily caloric and protein intake. Generally, the variation between the actual and recommended levels of caloric and protein intake can be better reflected through the assessment of adequate levels of both caloric and protein intake. Table 1: The daily caloric and protein intake for farm households in the traditional agricultural sector of Sudan: requirements and actual intake, 2008/09 Nutrient intake Caloric (kcal/day) Protein (g/day) Daily recommended intake 13,726 (4,868.58) 245.50 (88.88) Actual daily intake 8,801.26 (3,666.39) 327.09 (165.18) T- statistical test 12.07 6.41 P-value 0.000*** 0.000*** Remarks: Sample size = 200 farm households. The daily recommended intake for the average household size of about 6 persons. Number between brackets represents the standard deviation. T-test is paired sample test. *** significant level at p<0.01. The adequate levels of caloric and protein intake for the farm households are based on the difference between the actual levels and the required levels of caloric and protein intake. These levels for each household can be estimated by subtracting the actual levels of caloric and protein intake from the required levels. If the outcome is greater than or equal to zero, it means that the farm household has adequate levels of caloric and protein intake. However, if the outcome is less than zero, it means the farm household has inadequate levels of caloric and protein intake. Figure 1 demonstrates the adequate and inadequate levels of caloric and protein intake. It obviously seen from the figure that 18.5% and 66% of the rural households have adequate levels of energy and protein intake (i.e. the actual level is greater than or equal to the required level for the total household members). Thus, about 81.5% of the rural households are undernourished due to inadequate energy intake. Different outcomes were obtained from the study of Hashim (2008). He found that the adequate energy and protein intake for rural households were approximately 71.8% and 73.3% from the RDA, respectively. A recent study among the elderly in Botswana using a 24-hour food recall found that none of the elderly had an adequate energy intake, although they had an adequate amount of protein intake (Maruapula and Ck-Novakofski, 2010). A study on food diets of infants and preschool students stated the comparison between the level of nutrient intake and the recommended daily intake (RDI). The results found that both children aged 18-36 months and 37-60 months had a deficiency in energy intake (Ndiku et al., 2010). On the other hand, studies on energy intake among different age groups including children under-five years old found that the energy intake was low, as discussed by Al Jaloudi (2000) and Magboul et al. (2002). Energy intake was found to be below than the WHO-RDI for 12-14 years old boys and girls (Rahmatalla, 1999). Low energy intake was also obtained from the studies of Ahmed (1970), Mccance et al. (1971), and Abuzied et al. (2006) among university students. Similarly, Mohamed and El Amin (1998) showed the low energy of about 70% of the RDI in the Kongor district in the South part of Sudan. Low energy intake was attributed to lower dietary fat intake as discussed by Abuzied et al. (2006) and Magboul et al. (2002). The dietary food studies in Sudan were carried out in the assessment of energy consumption, which represents an important nutrient intake for the people. The Committee on International Nutrition (IOM, 1995) recommended a minimum of about 2,100 kcal/day for refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) in order to provide sufficient food energy intake for reasonable activities. Interestingly, only Khartoum, Gezira, and the Northern States met the level of minimum caloric requirements. The population in the remaining states received a daily energy allowance less than that of the recommended intake level by the Committee of International Nutrition. 8 120 ≥ Requirement Level < Requirement Level % of the Farm Households 100 18.5% 80 66% 60 40 81.5% 20 34% 0 caloric Protein Figure 1: Level of caloric and protein intake for the farm households in the traditional agricultural sector of Sudan during season 2008/09 Model Results The manner of conducting and dealing with the binary logistic model may require the identification and the nature of the dependent variable. In this case, the dependent variables are discrete variables (dichotomous), which take the value 1 if the farm households have an adequate level of caloric or protein intake. The levels of caloric and protein intake are supposed to be the dependent variables, which take the dummy values 0 and 1. Therefore, there are two dependent variables used to create two predicted models. Table 3 reveals the definition of the dependent variables used in the logistic regression model. It is clear from the table that 18.5% and 66%, of the farm households have adequate levels of both caloric and protein intake, respectively. Table 3: Definition of the dependent variables used in the logistic regression model Dependent variables Caloric Definitions of the dependent variables 1= Adequate level (≥ requirement level) 0= Otherwise Protein 1= Adequate level (≥ requirement level) 0= Otherwise Remark: Sample size = 200 farm households. Frequency 37 163 132 68 Percentage (%) 18.5 81.5 66 34 Table 4 demonstrates the summary statistics and the expected sign of the socioeconomics and farming characteristics used as explanatory variables in the binary logistic regression models. The average farm size for the farm households is about 14.75 ha. The descriptive statistic exposes that the farm households cultivate an average of three of crops. The average cereal food saved for home subsistence (sorghum and millet) is very low and is estimated to be about 305.22 kg/year. The average household income (farm, off-farm activities, and remittance) is about 1,331.11 SDG/year with a minimum of about 100 SDG/year and maximum income of about 5,300 SDG/year. The table also reveals that the average years of schooling for the head of the farm household is about 3.7 years. Also, the average household size is about 6 persons with a maximum number of 11 persons. The household size is characterized by higher dependency members in the households. Furthermore, the table shows that the head of the household has an average age of about 47 years. It is clear from the table that the male-headed household group represents about 81.5% compared to the female group. Also, about 81% of the farm households have ownership of livestock. 9 Table 4: Summary statistics and expected hypothetical signs of the explanatory variables used in the binary logistic models Expected hypothetical signs Explanatory variables Value Caloric Protein Average farm size (ha) 14.75(8.42) -/+ -/+ Average number of crops cultivated 3.92 (1.6) Average total cereal saved for subsistence (Kg) 305.22 (260.0) + + Average total household income (SDG/Year) 1,331.11 (830.42) + + Average education (Year) 3.7 (3.2) Average household size (Person) 6.1 (2.0) + + Average age of the head of the households (Year) 47.03 (12.72) Percentage of male-headed households (%) 81.5% + + Percentage of ownership of Livestock (%) 81% Remarks: Sample size = 200 farm households. Numbers between brackets are standard deviation. The level of calories consumed by individuals is used as an indicator of household food security status. The household that does not meet the minimum requirement of energy intake is regarded as food insecure or undernourished (Smith et al., 2006, found in Babatunde and Martinetti, 2010). In this case, the food-secure household can be defined as one whose caloric intake (energy) is greater than or equal to the energy requirement level for the households. In view of that, the results of the binary logistic regression that describe the factors influencing the adequate energy intake for the farm households are depicted in Table 5. It clearly shows that the socioeconomic factors consisting of total household income, household size, education, and gender are the important factors that shape the situation of energy intake among the farm households. The overall model is highly significant. This can be explained by the significant value of chi square being about 69.59 at level p<0.01 and the low level of log likelihood (-60.986). The total household income (SDG/year) is positively and highly significant with regards to the adequate level of energy intake (p<0.01). The interpretation of the odds ratio shows the predicted change in odds for a unit increase in the predictor if the other variables remain unchanged. The odds ratio of total household income (SDG/year) is about 1.00101. This means that with an increase of the total household income (SDG/year) by one SDG per year, this will lead to a 1.00101-fold increase in the odds that the household will consume an adequate level of caloric intake, all other variables remaining constant. This outcome is expected because an increase in household income means an increase in access to food. Similar findings concerning the impact of the household’s income on caloric intake was obtained from the study of Babatunde et al. (2007). They found that the higher the household income, the higher probability that the household would be food secure. Moreover, the effect of income on energy intake was inconsistent with the outcome from the study of Omotesho et al. (2006), Babatunde and Martinetti (2010), and Babatunde and Qaim (2010) in rural Nigeria. However, an insignificant effect of off-farm income using a probit model was found from the study of Oluyole et al. (2009). Gender is negative and significant with regards to the adequate caloric intake at level p<0.10. The odds ratio of gender is about 0.24430, meaning that being a male-headed household will lead to a 0.24430-fold decrease in the odds that the household will consume an adequate amount of caloric intake, all other variables remaining constant. This indicates that the female-headed households contribute positively to food security. A dissimilar result was obtained by Babatunde and Qaim (2010). They found an insignificant impact of being a male-headed household on the food security status of the households. This outcome also disagreed with the findings from the study of Babatunde and Martinetti (2010) and Babatunde and Qaim (2010). They argued that being a male headed household positively influenced the household caloric supply per adult equivalent. Another study reflecting the impact of female-headed households on the adequacy of caloric consumption was obtained by Mauro et al. (2006). They pointed out that female-headed households positively influenced caloric consumption adequacy in Albania, while it has no significant impact on the caloric consumption adequacy in Madagascar. The household size negatively and significantly impacts on the adequate energy intake at level p<0.01. The odds ratio of household size is about 0.37489. This means that with an increase the average household size by one person, this will lead to a 0.37489-fold decrease in the odds that the household will consume an adequate energy intake, all other variables remaining constant. The negative impact of household size on the adequate level of energy intake is mainly due to the higher number of dependent members. The significantly large number of household members who are not fully employed creates a heavy dependence on the few income earners within the households. As consequence, a reduction in the overall daily caloric intake for the household occurs. Inconsistent 10 results regarding the impact of household size on caloric intake emerged from the study of Orewa and Iyanbe (2010). They found that caloric intake increases with an increase in the household size in the rural area of Nigeria. An insignificant impact of household size on adequate caloric consumption was obtained by Mauro et al. (2006) in both Albania and Madagascar. The education of the head of the households (years) is significant and positive with regards to the adequate energy intake at level p<0.05. The odds ratio of education is about 1.23535. This means that with an increase in the education level for the head of the household by one year, this will lead to a 1.23535fold increase in the odds that the household will consume an adequate energy intake, all other variables remaining constant. A similar outcome showed the impact of education status for the head of the household on food security. The households with an educated head are more likely to be food secure than those with an uneducated one (Babatunde et al., 2007). An insignificant impact of education emerged from the studies of Oluyole et al. (2009) and Babatunde and Martinetti (2010). Significant and negative impacts of education on food security status were found from the study of Babatunde and Qaim (2010). Positive and highly significant effects of education on caloric consumption adequacy were discussed in the study of Mauro et al. (2006) in both Albania and Madagascar. A positive education level of household members was discussed in the rural and low-income urban areas in Nigeria (Orewa And Iyanbe, 2010). A negative and significant impact of education on household food security was found in the tea and coffee zone as well as in the tea zone in Kenya. Conversely, a positive and significant impact of education on food security was obtained from the coffee zone in Kenya (Nyaga and Doppler, 2009). Likewise, the age of the head of the household (year) is insignificant with regards to an adequate caloric consumption. Parallel results concerning the impact of age of the head of the household on food security in the coffee zone emerged from the study of Nyaga and Doppler (2009) in Kenya. An insignificant impact of age of the head of the households on an adequate caloric consumption was obtained by Mauro et al. (2006) in both Albania and Madagascar. Additionally, the age of the head of the households was found to be insignificant with regards to the household’s calorie supply in rural Nigeria as argued by Babatunde and Martinetti (2010). However, the age of the head of the household was positive and significant among the households in both tea and coffee as well as tea zones as discussed by Nyaga and Doppler (2009). A negative and significant impact of the age of the head of the household on household calorie supply emerged from the study of Babatunde and Qaim (2010). Furthermore, negative and significant impacts of age of the head of the households on food security status was argued by Babatunde et al. (2007) and Oluyole et al. (2009) in Nigeria. The farm size (ha) is insignificant with regards to the adequate level of caloric consumption. Dissimilar findings were obtained from the study of Nyaga and Doppler (2009), in which the percentage of land cultivated under cash crops was significant and negatively influenced the food security in the tea and coffee zone, tea zone, and coffee zone as well. They also tested the percentage of land cultivated under food crops; however, the outcome was found to be positive and significant in both tea and coffee zones and in the tea zone as well. A significant and positive impact of farm size on household calorie supply was obtained from the studies of Babatunde and Martinetti (2010) and Babatunde and Qaim (2010) in Nigeria. An insignificant outcome regarding the impact of the percentage of land cultivated under food crops on food security was found in the coffee zone in Kenya (Nyaga and Doppler, 2009). A positive impact of farm size on food security was obtained from the study of Omotesho et al. (2006) in Nigeria. Insignificant impact of farm size on food security status in Nigeria was also discussed by Babatunde et al. (2007). Furthermore, the logistic regression model reveals that the farming factors including the ownership of livestock, the number of crops cultivated and total cereal saved for home subsistence (kg) are insignificant with regards to the adequate level of energy intake. The logistic regression result of protein intake is revealed also in Table 5. The overall model is significant (chi square = 61.61***). The value of log likelihood is about -97.403. It clearly appears from the table that the socioeconomic characteristics of household income (SDG/year), household size, and age of the head of the household are significant factors influencing the adequate level of protein intake. The total household income (SDG/year) has a significant and positive impact on the adequate level of protein intake at level p<0.01. The odds ratio of total household income (SDG/year) is about 1.00127. This means that with an increase in the total household income (SDG/year) by one SDG per year will lead to a 1.00127-fold increase in the odds that the household will consume an adequate level of protein intake, all other variables remaining constant. Analogous results emerged from the regression analysis conducted by Iyangbe and Orewa (2009). They employed various functional forms to analyze the determinant factors of protein intake among rural and low-income urban households in Nigeria. They reported that the total household monthly income was highly significant using both semi-log and double-log function forms; nonetheless, it was insignificant using the linear function form in the rural 11 area of Nigeria. A high significance of total household monthly income was found in the urban area using linear, semi-log, and double-log function forms (Iyangbe and Orewa, 2009). The household size is negative and significant with the adequate protein intake at level p<0.01. The odds ratio of the household size is about 0.58088. This means that an increase in household size will lead to a 0.58088-fold decrease in the odds that the household will consume an adequate level of protein intake, all other variables remaining constant. Similar findings were obtained from the study of Iyangbe and Orewa (2009). They found that the household size was negative and highly significant with regards to protein consumption intake in the rural area of Nigeria using linear, semi-log, and double-log function forms. Nevertheless, the household size was insignificant with regards to protein consumption in the urban areas of Nigeria using linear, semi-log, and doublelog function forms as reported by Iyangbe and Orewa (2009). Age of the head of the household is negative and significant with regards to adequate levels of protein intake at level p<0.05. The odds ratio of age of the head of the household is about 0.96086. Thus with older household heads, this will lead to a 0.96086-fold decrease in the odds that the household will consume an adequate level of protein intake, all other variables remaining constant. A positive and significant impact of the age of the household members on daily protein intake among rural and low-income urban households was found in the study of Iyangbe and Orewa (2009), using three functional forms of multiple regression models. Gender and education are insignificant with regards to adequate levels of protein intake as depicted in Table 6. This outcome disagrees with findings from the study by Iyangbe and Orewa (2009). They argued that the education level of the household members was highly significant in the urban area, using three functional forms of the multiple regression models (linear, semi-log, and double-log). Likewise, the education of the household members was found to be highly significant in urban areas by using linear and double-log function forms, while it was insignificant with the semi-log function form in the rural area, as argued by Iyangbe and Orewa (2009). Moreover, the logistic regression model shows that the farming factors of farm size (ha), total cereal saved for home subsistence (kg), the number of crops cultivated at the household level, and ownership of livestock are insignificant with regards to adequate level of protein intake. Table 5: Factors influencing the adequate levels of caloric and protein intake in the traditional agricultural sector of Sudan, 2008/09 Independent variables Odds Ratio1 1.00101 Caloric1 Std. Err. z P-value Odds Ratio1 1.00127 Protein2 Std. Err. z P-value Total household 0.00032 3.13 0.002*** 0.00031 4.15 0.000*** income (SDG/Year) Household size 0.37489 0.06466 -5.69 0.000*** 0.58088 0.06281 -5.02 0.000*** (Person) Age of the head of 0.99528 0.01978 -0.24 0.812 0.96086 0.01696 -2.26 0.024** the households (Year) Education (Year) 1.23535 0.12418 2.10 0.036** 0.97955 0.06633 -0.31 0.760 Male-headed 0.24430 0.18406 -1.87 0.061* 1.70135 0.93740 0.96 0.335 households Farm size (ha) 0.95622 0.02884 -1.48 0.138 1.00093 0.02132 0.04 0.965 Ownership of 0.46113 0.28234 -1.26 0.206 1.05954 0.49137 0.12 0.901 livestock Total cereal saved for 1.00078 0.00084 0.92 0.355 1.00033 0.00066 0.51 0.612 subsistence (Kg) Number of crops 0.81545 0.14217 -1.17 0.242 1.24243 0.178349 1.51 0.130 cultivated Remarks: Number of observations = 200 farm households 1Log likelihood = -60.986. LR chi2 (9) = 69.59***, Pseudo R2 = 0.36. 2Log likelihood = -97.403. LR chi2 (9) = 61.61***. Pseudo R2 = 0.24. The significant at ***P<0.01, **P<0.05, *P<0.10. Exp (B) shows the predicted change in odds for a unit increase in the predictor. 12 4. Conclusion and Recommendations The outcome of this paper revealed the existence of malnourished and undernourished among the farm households due to the inadequate consumption levels of both caloric and protein intake. This condition occurred as consequence of inaccessibility to food, low household income, and insufficient food consumption, as well as an imbalanced of foods diet. The logistic regression models showed that gender, total household income, and household size were crucial socioeconomic characteristics that influence the adequate level of caloric intake. Maleheaded households has negatively affected the adequate level of caloric intake compared to their female counterpart. The total household income positively influenced the adequate levels of both caloric and protein intake. The household size has negatively influenced the adequate levels of both caloric and protein intake. The age of the head of the household has negatively affected the adequate level of protein intake. Accordingly, this paper suggests to develop a national food composition tables and computer databases for food consumption. Also, conduct of periodic nutrition surveys is necessarily essential in order to evaluate the dietary intake particulary for the vulnerable people. Further, the paper recommends to create a national reference values for intake (RDA and AIs) as well as, to launch a major nutrition program to improve the nutrition situation among the farm households. The nutrition program would help to improve the daily food diets and food diversity as well as the attitudes and capacity building for the rural people. This programe should be associate with different policy strategies that seek to improve the level of farming system and households income. Eventually, support the role of female in the rural communities is essentially required to improve the nutrient intake. References Abuzied, I.H., Nour, A.Z.A.M., and Magboul, B.I. (2006). Nutritional status of University of Khartoum students during 18 months period. Food Research Centre J.Fd.Science. & Technology, 1:67-74. Ahmed, N. (1970). Energy in food offered to Sudanese medical students and their energy expenditure. Sudan Med. J., 8(11):31-36. Al Jaloudi, A. E. (2000). Assessment of the nutritional status and household food security in the poor urban areas in Khartoum state: case study “Marzouk”. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Khartoum, Sudan Babatunde, O.A. Omotesho and O. S. Sholotan (2007). Socio-Economics characteristics and food security Status of farming Households in Kwara State, North-Central Nigeria. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 6(1): 49-58, 2007.ISSN 1680-5194 © Asian Network for scientific Information. Babatunde, Raphael O. and Martinetti, Enrica C. (2010). Impact of remittance on food security and nutrition in rural Negira. March, 2010. Babatunde, Raphael O. and Qaim, Matin (2010). Impact of off-farm income on food security and nutrition in Nigeria- Food Policy. Volume 35, Issue 4, August 2010, Pages 303-311-Journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodpolicy. Bartali B., Frongillo EA., Bandinelli S., Lauretani F., Semba RD., Fried LP., and Ferrucci L. (2006). Low nutrient intake is an essential component of frailty in older persons. Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-6301, USA. bb232@cornell.edu. 2006 June; 61(6):589-93. Boutros, J.Z. (1986). Sudan Food Composition Tables, 2nd edition. National Chemical Laboratories, Ministry of Health, Khartoum, Sudan. Chao-Ying Joanne Peng, Kuk Lida Lee, and Cary M.Ingersoll (2002). An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. Indiana University-Bloom ington, September/October 2002 vol.96 (No.1). El Bashir H. (1999). Social Structure, Ethnic Relations and Land Tenure Systems in Rural Sheikan Province. Consultant Report Produced for ADS, El-Obeid, Sudan. Elamin M.E., Musa H. and Er Rahil I. (2009). Reconciling the trade-offs between domestic demand and export market: The case of Sudan dry land Agriculture. Published under the book of economics of the resource use and farming systems development in the Middle East and EAST AFRICA. Margraf publishers GmbH, 2009. Elkhidir, E. E. (2003). Economic Efficiency of Sharecropping in Dry land: A case Study of Gum Arabic Production in Kordofan Gum Belt, Sudan”. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Putra, Malaysia. Faki H., Nur E. M., and Abdelfattah A. (2009). Poverty assessment and mapping in Sudan, Final draft progress Report North Sudan. ARC & ICARDA. FAO (1968). Food Composition Table for Use in Africa. A Research Project Sponsored Jointly By U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Health Services and Mental Health Administration National Center for Chronic Disease Control Nutrition Program Bethesda, Maryland 20014 and Food Consumption and Planning Branch Nutrition Division Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy 1968 . Available online at: http://www.fao.org/do crep/003/X6877E/X6877E00.htm 13 FAO (1994). Food and nutrition in the management of community nutrition. FAO-Near East regional office, Cairo. Pp.148-149. In Arabic. FAO (2001). Improving Nutrition through Home Gardening -A Training Package for Preparing Field Workers in Africa-Nutrition Programmers Service Food and Nutrition Division -Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2001. FNB (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. National Academy of Sciences. Institute of Medicine. Available online at: www.nap.edu. Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis. Fourth Edition. Prentice Hall. USA.1004 pp. Hashim S. I. (2008). Poverty, food security and malnutrition in an urban and rural setting: case study the former west kordofan state-Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis department of family science-faculty of education-university of Khartoum, May, 2008. IOM (1995). Estimated mean per capita requirements for planning food aid rations. National Academy of Science, Committee on International Nutrition, Washington, D.C. Iyangbe C.O. and Orewa S. I. (2009). Determinants of daily protein intake among the rural and low in come urban Households in Nigeria. American-Eurasian Jorunals of Scientific Research 4(4):290-301, 2009. Jennifer J. Otten, Jennifer Pitzi Hellwig and Linda D. Meyers (2006). Dietary reference intake (DRI): the essential guides to requirements. Institute of the medicine of the national academies. Maeve C. Cosgrove, Oscar H. Franco, Stewart P. Granger, Peter G. Murray and Andrew E. Mayes (2007). Dietary nutrient intakes and skin-aging appearance among middle-aged American women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 86, No. 4, 1225-1231, October 2007, American Society for Nutrition. Magboul, B.I., Mohamed, K.A. and El Khalifa, M.Y. (2002). Dietary iron intake and prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among under-five children in Khartoum State. Report to EMRO/WHO, Project EM/ICP/RPS/002. Maruapula Segametsi and Ck-Novakofski (2010). Nutrient intake and adequacy of Batswanar elderly. African Journal of food agriculture nutrition and development- Volume 10 No.7-July, 2010. Mauro Migotto, Benjamin Davis, Gero Carletto and Kathleen Beegle (2006). Measuring food security using respondents’ perception of food consumption adequacy. Research paper No. 2006/88. This paper was prepared for UNU-WIDER project on hunger and food security: new challenges and new opportunities. Mccance, R.A., Hamad, E. N., Nasreldin, Widdowson, E.M., Southgate, D.A.T., and Passmore, R. (1971). The response of men and women to changes in their environmental temperatures and ways of life. Philos.Trans.R.Soc.Lond. (Biol), 259:533-65. MFEP (2008). Marketing of Agricultural Products in North Kordofan: Current Situation and Future Prospects. Book prepared by national expert team for the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning in North Kordofan State. Mohamed, K.A. and El Amin, Alawia (1998). Review of nutrition activities in Sudan. In’ interface between agriculture, food science and nutrition’- Proceeding of a national work in Sudan. ICARDA, Aleppo, Syria. Ndiku M., Jaceldo-Siegl K. and Sabaté (2010). Dietary pattern of infant and preschool children in Mwingi and Makueni districts of Ukambani region, Eastern Kenya-African Journal of food agriculture nutrition and development- Volume 10 No.7-July, 2010. Nyaga E. Kabura and Doppler Werner (2009). Combining principle component analysis and logistic regression models to assess household level food security among smallholder cash crop producers in Kenya. Quarterly Journal of international agriculture 48 (2009), No.1:5-23. Oluyole K. A., Oni O. A., Omonona B. T., and Adenegan K. O. (2009). Food Security among Cocoa Farming Households of Ondo State, Nigeria. ARPN Journal of Agricultural and Biological Science Vol.4 No.5 September, 2009. Omotesho, O. A., Adewumi, M. O., Muhammad-Lawal, A. and Ayinde, O. E. (2006). Determinants of food security among the rural farming households in Kwara State, Nigeria. Department of Agricultural Economics and Farm Management, University of Ilorin, Nigeria-Received April 29, 2006. African Journal of General Agriculture Vol. 2, No. 1 (2006). Orewa, S.I. and Iyangbe, C.O. (2010). Determinants of Daily Food Calorie Intake among Rural and Low-Income Urban Households in Nigeria Academic Journal of Plant Sciences 3 (4): 147-155, 2010-ISSN 1995-8986 © IDOSI Publications, 2010. Rahmatalla, H.M. (1999). Consumption patterns and anti-anaemic properties of guddiem (Grewia tanex). M.Sc. Thesis, University of Khartoum, Sudan. Smith L.C., Alderman H. and Aduayom, D. (2006): Food security in sub-Saharan Africa: New estimates from household expenditure surveys. Research Report 146, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC. 14 WFP (2006). Interim poverty reduction strategy paper (2004-2006). Background paper -Khartoum food aid forum 6-8 June, 2006. 15