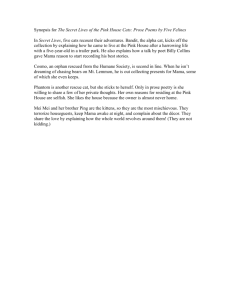

Add to Introduction - A Complete Analysis

advertisement