CONFERENCE PAPER No

advertisement

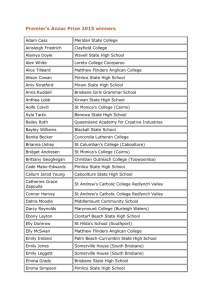

CONFERENCE PAPER No. 7 Senior Physical Education …blurring the boundaries between written and physical tasks… Presented by Damien Barry Senior Physical Education …blurring the boundaries between written and physical tasks… Damien Barry Prior to the 1998 Senior Physical Education syllabus release, there was a clear distinction between theory and practical content matter. The subject, then known as Health and Physical Education, encouraged little integration between the two areas. Subsequently, ‘Health’ and ‘Physical Education’ emerged as two distinct subject areas in their own right, and the 1998 syllabus for Physical Education (PE) sought to integrate the written components with the learning of physical skills together with a philosophy that underpinned learning called, ‘learning in, through and about physical education’ (Senior Physical Education Syllabus: 1998: 5) With the development of the 2004 Physical Education syllabus, the same philosophy remains, however, there is an increased focus upon the personalisation and integration of units of work with students. Units of work continue to integrate concepts with physical activities, however, there is further relevancy with the learning experiences and personalised assessment so that students for example, apply concepts of training methods and principles to improve their own performance and that of peers in the physical activity explored as part of that unit. At Clayfield College, this has been facilitated with the implementation of a variety of Thinking Skills and strategies. These include graphic organizers, especially sequence charts, Thinking Tools such as CAF (Consider All Factors), and the Six Thinking Hats. These cognitive tools and strategies provide effective scaffolding to the thinking and learning processes, enhancing the development of intelligent performers within PE. This paper will outline why the teaching of Thinking Skills in PE is critical and how this is achieved at Clayfield College. It will also examine, through the use of such tools, how both written and physical subject matter are integrated and personalised. The teaching of higher order thinking as an explicit skill within PE continues to be a challenge. Many teachers regard, or perhaps hope, this will be developed indirectly or just happen even though copious research suggests that thinking must be taught directly because students do not engage in critical thinking by themselves (Bellanca and Fogarty, 1994; Huot, 2000). Physical Educators not only need to teach thinking but also to incorporate it into the three domains, namely the cognitive, the psychomotor and the affective domains. The Queensland Senior PE syllabus is separated into three criterion or objectives for teaching and learning. Both written and physical performance assessment tasks are assessed using the same three criteria. These are “Acquiring, Applying and Evaluating”. There are also three focus areas from which subject matter that is to be covered across years 11 and 12 is selected. In Senior PE, higher order thinking skills are seen to be developed mostly within the third criterion, that is “Evaluating”. However certain key skills are learnt within the “Applying” criterion, eg. the ability to use concepts in new situations. According to the syllabus, “Evaluating” is achieved via hypothesizing, appraising, predicting, justifying and reflecting upon information. Reflecting upon information is seen to effectively move the learner into metacognition. The evaluating criterion is expressed in Bloom’s Taxonomy as synthesis and evaluation. Bloom’s Taxonomy presents six distinct levels of thinking, moving from lower order thinking skills to higher order thinking skills. The six levels from low to high are illustrated in Figure 1. Evaluation Synthesis Analysis Application Comprehension Knowledge Figure 1. Hierarchical Taxonomy Blooms According to Jensen (Brainwaves Conference, 2005), the frontal cortex of the brain, the area responsible for higher order thinking, only begins to mature in the teenage years. Therefore it is imperative that teachers provide sufficient support and tools to enable and guide students to develop these higher order thinking skills, especially if they are to be assessed in this area. One assumption of having the three levels of objectives is that thinking (evaluating) needs a cluster of knowledge in which to manipulate information (acquiring and applying). Thus as PE teachers much of our instructional time is devoted to acquiring and applying the information and little to evaluating. This may be because many teachers perceive thinking as an innate ability rather than a learnt skill. As Marzano (2001: 9) states, evaluation may actually preclude the acquisition of new knowledge. De Bono (1983: 703 - 708) further supports this by arguing that we may need to reduce the time we spend teaching information in order to focus on the direct teaching of thinking skills. However, PE teachers, due to a number of reasons such as time constraints, teaching to the test, or increased accountability, engage in largely direct teaching methods. Such teaching where the teacher decides the content matter, has managerial control, presents tasks, controls pacing and task progression further limits the ability to teach thinking. The teacher becomes a tool for the transmission of knowledge rather than a facilitator of learning, encouraging learned helplessness and laziness within students. Tasks should be structured so that pupils own the information gathering and thinking processes. This has ramifications for students attempting to fulfill the evaluation objective. These higher order thinking skills seem to be insufficiently taught in PE. McBride (1999: 219) points out that most PE teachers use the traditional demonstration / replication instruction model where they control most, if not all decision making. PE classes often spend much time on learning skills to play the game rather then learning a game by playing it. Therefore students miss out on opportunities to use their recently acquired knowledge in meaningful contexts. In addition, too often PE Educators do not model effective thinking skills. It is important for PE teachers to not only be knowledgeable about the topic, but also be good role models for critical thinking (McBride, 1995: 23). This is supported by Howarth (2000) who suggests that the development of thinking skills within a PE setting often demands fundamental and difficult changes for any teacher, requiring a change in curriculum and teaching style since students are influenced by the way teachers examine their own thinking and encourage others to do the same. Furthermore if teachers are to teach cognition and metacognition, teachers themselves must understand it (Tishman and Perkins, 1995). At Clayfield College, the ability of students to reflect and appraise their own and peer physical performances has been greatly enhanced with the use of CAF’s (Consider All Factors thinking tool). The development of written assessment tasks, such as research reports, have also benefited with the student use of graphic organizers and thinking tools. Those teachers who take the time to model, encourage and discuss the use of these tools have achieved the best outcomes for students. This leads to the question of what are the contemporary learning theories appropriate to the development of higher order thinking in school Physical Education? It appears that indirect teaching methods are the most effective in encouraging students to think creatively, to appraise, formulate, predict and implement knowledge. Therefore models such as Teaching Games for Understanding (Werner, Thorpe and Bunker, 1996), Metzler’s (2000) Cooperative Learning, Mosston and Ashworth’s Spectrum of Teaching Styles (1994) and Siedentop’s (1994) Sport Education Model are ways of achieving this. Essentially, models in which the student is the centre of learning, where the teacher poses problems to be solved and facilitates the learning environment rather than directs, are the most effective. What is also required is the attainment of metacognition or the ‘thinking about thinking’. This is an objective within PE classes across all year levels at Clayfield College. By infusing Thinking Tools into everyday teaching we are able to cover the content matter, negate the time constraints experienced by all teachers, and develop metacognitive skills and mindfulness. Clayfield College has a Thinking focus with a coordinator dedicated to implementing thinking skills, tools and strategies across the curriculum. All teachers are provided with in-service to implement the strategies in their day to day teaching and students are provided with regular thinking skills sessions embedded into their timetable. These sessions introduce and expose students and teachers to these tools and strategies and provide a subject specific context. In PE these strategies have been extremely beneficial in developing cognitive skills and assisting in the integration of written and physical performance subject matter. Sequence chart graphic organisers are used to structure the orienteering learning process (see Appendix A). Other graphic organizers are used to assist students to plan and structure written tasks more effectively, e.g research reports and to develop a six week training plan to improve physical performance (see Appendix B). The Six Thinking Hats are used to help students plan and evaluate their aerobics routines (see Appendix C). The written subject matter was ‘learning physical skills and information processing’. The Six Thinking Hats enabled students to apply these concepts in the construction of a physical routine by identifying strengths, weaknesses, distractions, emotions and needs. The same tool has been used by Year 10 Health and PE students to revise a unit on energy systems, training principles and training methods in relation to volleyball and dance /aerobics (see Appendix D). The results of the implementation of these tools are multifunctional. The Thinking Tools and strategies o o o o o o o provide a thinking scaffold. enable students to consider a broader range of content knowledge. enhance planning and time management. promote self reflection of optimum learning practices for each individual. allow students to do the thinking and work themselves. develop a greater quality and depth of content understanding and thinking. improve student confidence to apply these tools to a raft of scenarios and tasks across both physical and written domains. The challenge now is to totally infuse these strategies into PE students’ schema so that they are able to perform these strategies without teacher, sheet and stimulus items to guide them! The initial implementation of these Thinking Tools at Clayfield College was met with some resistance from both teachers and students, and continues in some areas today, because with change comes fear and uncertainty. Teachers are encouraged to appraise their current teaching methods and students are required to understand, transfer and use information rather than to simply regurgitate the information. The concept of ‘learned helplessness’ within students is being challenged. The current cohort of Year 11 students were the first group as year 8’s to be exposed to the Thinking Tools and each year since has seen a gradual ‘roll out’ of subsequent thinking tools and strategies. Terms such as CAF, O.P.V (Other People’s Views), A.G.O (Aims, Goals, and Objectives) and the Six Thinking Hats are part of everyone’s lexicon at Clayfield College. Teachers can now ask students to perform a CAF and students know exactly what is expected of them and how to use this tool. The ability to integrate and personalize concepts is a difficult task. PE assessment tasks must be developed that require students to do this, however learning experiences must effectively prepare students and equip them to fulfill this requirement. It is especially difficult if students are immersed in a system that separates ‘theory’ from ‘practical’ throughout Years 8, 9 and 10 and even more if this is a continuation from Primary School. Physical tasks are seen as something we do outside on a court or field. ‘It is just sport’. Students cannot be expected to simply switch from one paradigm to another as soon as they enter Year 11. This hurdle has been recognized at Clayfield College, and tasks have been developed to integrate ‘theory’ and ‘practical’ content matter in Years 8, 9 and 10, e.g. whilst exploring Athletics year 8 students are subjected to a battery of fitness tests and write a one week training program to improve their performance in an athletics discipline and overall wellbeing. Whilst exploring fitness components and training methods year 10 students apply this knowledge and understanding to the sports explored throughout the unit, i.e. aerobics and volleyball. The Thinking tools and strategies used at Clayfield College are exactly that, TOOLS. Each tool/strategy has a specific task and therefore a specific use. Knowing the use and task for each tool, enables the learner and teacher to select the appropriate tool to accomplish a specific Thinking Task. No one model or tool is best suited to the teaching of thinking within the Physical Education context, rather what is needed is an explicit desire and commitment to teach thinking, a structured methodology in which to pursue this commitment and PE educators themselves to want to change the way they structure learning experiences and to model effective thinking tools and strategies that develop creative thinkers, but also to blur the boundaries between the written and physical domains of PE creating a wholeness rather than isolated, stand-alone blocks of information and knowledge. References Bellanca, J. and Fogarty, R. (1994). Blueprints for Thinking in the Co-operative Classroom (3rd ed.). New York: Hawker Brownlow Education. De Bono, E. (1983). ‘The Direct Teaching of Thinking as a Skill”. Phi Delta Kappan, 64 (10), 703 – 708. Huot, J. (2000). ‘Understanding Thought Processes for Improved Teaching of Thinking’. http://fox.nstn.ca/~huot/model-tk.html Howarth, J (2000). ‘Contributions of Research on Student Thinking in Physical Education’. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education. 16 (1), 262 – 277. Jensen, E. 2005. Brainwaves Conference, Sunshine Coast, Australia. Marzano, R. J. (2001). Designing a New Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, California: Corwin Press Inc. McBride, R.E. (1995). ‘Critical Thinking in Physical Education An Idea Whose Time Has Come’. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 66 (6), 21 – 52. McBride, R. E. (1999). ‘If You Structure It, They Will Learn – Critical Thinking in Physical Education Classes’. Clearing House, 72 (4), 217 – 220. Mosston, M. and Ashworth, S. (1990). The Spectrum of Teaching Styles – From Command to Discovery. New York: Longman Press. Queensland Studies Authority (2004). Senior Physical Education. Siedentop, D. (1994). Sport Education. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics. Tishman, S. and Perkins, D. N. (1995) Critical Thinking and Physical Education. JOPERD, 66 (6), 24 – 30. Werner, P., Thorpe, R., and Bunker, D. (1996). ‘Teaching Games for Understanding – Evolution of a Model’. JOPERD, 67 (1): 28 – 33. Dispositions Thinking Tools Skills Knowledge Rheault, C. von Oppell, M.A. 2005: Putting it All Together. Workshop presented at the 12th International Conference of Thinking, Melbourne, July 2005.