Signifying Scriptures: Enduring Themes and Motifs Associated with

advertisement

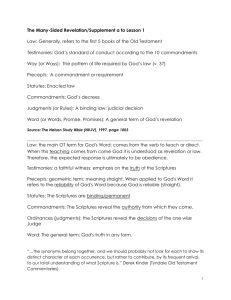

Signifying Scriptures from an African Religious Perspective By Oyeronke Olajubu Department of Religions University of Ilorin, Nigeria oyeronkeolajubu@yahoo.com Preamble Indigenous religions are usually characterized by plurality. This plurality is displayed in the components and contexts of some indigenous religions, and may be manifest in ritual performance as a pre-mediated move or an unplanned occurrence. This consciousness of the “plural” in indigenous religions renders normative paradigms inadequate to the people’s lived experience; rather the emphasis is on mutuality, accommodation, and balance. The Yoruba religion is one of such indigenous religions that prioritize balance and mutuality in relationships between God and humans, humans and nature, and in interpersonal relationships. Dividends of this stance could be discerned in power relations, gender relations, and power utilization among adherents of Yoruba religion. The agenda of the Institute for Signifying Scriptures seeks to problematize the use of normative paradigms in the definition and conceptualization of what “scripture” is. Notions of “scripture” in “major” world religions seem restrictive and in need of expansion to cater to other people’s religious inclinations. This attempt touches directly on some issues in African religion, especially in the realm of rituals, the exposition of which may facilitate, albeit in a minimal way, the agenda of the Institute for Signifying Scriptures. 2 My aim in this paper is to relate some identified themes and motifs in the introductory essay by Vincent L. Wimbush to African religious traditions. I identified some salient themes and motifs in Wimbush’s essay as submitted by some scholars. These motifs and themes will be discussed in seven sections, each of which addresses pronouncements by scholars in Wimbush’s essay. Some analyses of issues may overlap during the discourse. Mueller—“Scriptures” as the ultimate, discontinuous medium of the sacred1. Mueller identifies “scriptures” as one of the mediums of communication of the sacred to humans. It would be misleading to present “scriptures,” whether written or oral, as the single medium of communication from the sacred to humans. The dynamism of religious life and experiences makes the above submission implausible2. In non-dominant religions for instance, rituals and performance constitute a veritable means of communication on diverse issues from different perspectives. These may include invocations, rites of passages and spirit possession. In African religion, such rituals exhibit features of spontaneity and fluidity in as much as activities in performance and recitations are neither fixed nor static. Cultic functionaries who officiate or offer direction during each ritual occasion often operate under the influence of a supersensible power with whom they are in constant communication and whose dictates they communicate to worshippers. There is therefore a continuous web of interpersonal exchange of information and disposition in this process of assessing “scripture.” Again, when it is recalled that the act of “defining” is itself an attempt to set boundaries, it is recognized that a phenomenon as 3 dynamic as the communication between the sacred and humans may not be constrained to a single medium. The occasion that resulted in Mueller’s comment clearly calls for intelligent and in-depth analysis of what constitutes “scripture,” its meaning and social relevance. This is especially compelling because Mueller describes African people as not having the “They do not desire to believe in the almighty creator of heaven and earth, let alone fear, love and have faith in Him-----If one talks to them of God’s miracles and gracious works---some of them listen in amazement, but most scoff”3. It may be tempting to consider this statement by Mueller as belonging to an era that is past and long forgotten, but such a statement, sometimes in a different form, continues to fuel the impartation of normative concepts and principles in religion and one of such is the issue of “scripture”. “Scripture” had been taken in history to refer to written prescriptions for humans from the Supreme Being4. Embedded within “scripture” are explanations for nature (cosmology and cosmogony), expectations for interpersonal relationships (ethics), and stipulations for contact between the supersensible world, humans, and the eco-system (ritual). A salient feature of “scripture” has been its normative character. Though “scripture” as used in dominant religions display different levels of dynamism in interpretations, it nonetheless remains normative. In African religions “scriptures” would be a fluid phenomenon, which is marked by multiplicity. This would be especially true of the ritual sphere where a continuous process of communication and interaction occur in African religions. A crucial product of these interactions between the divine and humans involves prescriptions of diverse modes, which would qualify to be labeled as scriptures. 4 Worthy of mention is the role played by custodians of “scripture” in these enterprises. The profound influence of these custodians over dogma and ritual in religion turns around notions of restrictive knowledge, which is assumed to bestow authority. In a certain parlance, this authority may not be challenged. These observations point towards a restricted definition of what constitutes-"scripture,"-the boundary of which is immutable. Realities in some societies render such definitions and conceptualizations impractical and inadequate. The word “discontinuous” in the statement after Mueller’s comment deserves some consideration. A discontinuous medium suggests one that is not stable; one that is on and off, the question to ask is this: is this discontinuous-ness the prerogative of the sacred? In which case the sacred may use this medium designated “scripture” to communicate with humans sometimes but may choose to employ other means at other times; or is it a case of discontinuous-ness on the part of humans in accessing and understanding this medium designated “scripture” at some times? Whichever way the response goes, the term “scripture” conveys notions of complexity and dynamism. Smith—What is “Scripture”5? Traditionally, “scripture” as a term in religious discourse is a text linked with a sacred being or sacredness. It is usually written and fixed. Sometimes it is subject to scientific analysis (hermeneutics); sometimes it is not. These predictable and boundarybound classifications of “scripture” have however proven inadequate for certain societies on account of the mark of dynamism in the religious experience of such a people. So what is scripture? As a concept, “scripture” would appear to exhibit a close affinity with 5 the history, culture, and social order of a given people. It would seem to encompass a people’s meaning system and process of legitimization. It would therefore be regarded as a broad concept with a complex agenda. Nonetheless, “scripture” is not expected to be culture bound, in which case any “scripture” should be universally accessible insomuch as its prescriptions are agreeable to individuals who subscribe to it, irrespective of the nationality or cultural affiliations of such individuals. The case of Yoruba religion may be cited as an example. Scripture in Yoruba religion is coded, but not static, or closed. It encompasses oral narratives (Ifa, corpus, stories, legends, incantations, and proverbs), some of these oral sources are now documented. In addition, Yoruba scripture includes prescriptions that emanate from daily enactment of ritual through diverse modes of performance and recitations. Often this involves recitation of praise names (oriki) for the orisa, which may result in spirit possession from which messages are transmitted to worshippers. Hence the content of Yoruba scripture is dynamic and multifarious. Nonetheless, its prescriptions are agreeable and accessible to people worldwide irrespective of nationality or cultural affiliation. Consequently, there are adherents of Yoruba religion who are Yoruba by origin and others who are non-Yoruba. Also Yoruba religion is practiced with minor modifications in places such as Cuba, Brazil, Trinidad and Tobago, Germany and North America. Maybe an attempt at considering what “scripture” should not be is worthwhile at this point. “Scripture” is not a sole reference to written text, a finished product, that exercises normative influence on people’s lives but may not be influenced by the experiences of such a people in anyway. “Scripture” is not an oral text that exists apart from the experiences of a people or an individual but seeks to exert normative influence on a 6 group of people. “Scripture” is not a written or oral text that is closed or sealed to analysis, appraisal, and some level of “negotiations”. Furthermore, scripture may be located in African social settings as well due to the permeating feature of religion in African worldview. This is especially true of the people’s use of language, which could be direct or indirect. In the recitations of praise names of individuals, lineages or communities for example, the process of recitation and memory recall could produce salient socio-cultural paradigm that impacts the people’s religious consciousness significantly. Wimbush---What are Scriptures? Whence Scriptures Developed, how Scripture Functioned6? The availability of many “scriptures” in the religious experiences of human beings portrays pluralism. How do “scriptures” fare in the face of religious pluralism? Does the presence of many “scriptures,” whether written or oral, not suggest the futility of constraining “scriptures” not only in number but also as a concept? For example, all the definitions I checked for scriptures assumed they were written documents, ignoring the fact that there are oral scriptures in existence. Therefore the need to reflect a broader perspective in the definition of “scripture” is pertinent. This should be a crucial concern to anyone involved with any writing project that contributes to the definition and conceptualization of “scripture.” The development of the concept of “scripture” could not have occurred in a vacuum. In some instances, records of the encounter between the sacred and humans are kept in oral or written forms to serve as encouragement, reproof, and examples for the 7 living adherents of such “scriptures” (Bible). In some cases, in addition to the records of encounters between the sacred and humans, the sayings and conduct profile of a religious leader are also recorded to serve as a model for those who subscribe to such “scriptures” (Quran). Again, at other times, records are kept in written or oral forms of ancient accounts that proffer explanations for events and past occurrences that history could not explain (Bhagavad-Gita). On other occasions, “scriptures” develop as accumulated recordings of philosophies and practices espoused by a key figure with profound influence on the lives of the society (Tao Te Ching). Germane to the various forms of developmental procedures identified above is the human agency. The trail of information from and about the sacred and the encounter between the sacred and humans necessarily passes through the human agency. Consequently, the influence of the experiences of human beings as a significant factor on the interpretations of received information in the religious sphere cannot be undermined. The interpretation of any information by an individual carries with it aspects of who the individual is, where (s)he has been, and what the individual prioritizes. Unavoidable, then, is the issue of interpretation, which eventually resulted in what is now designated as “scripture”. The development of “scripture” is thus intertwined with the lived experiences of the human agency through which it was communicated. However, the adherents to these “scriptures,” who are also having varied living experiences, may not have the opportunity to influence these “scriptures” in a way that the “scriptures” handed over to them have been able to influence their lives. In some instances, this may pose a problem, due to the dynamism of people’s lived experiences. An example is the sharia legal system in a religiously pluralistic society that is Nigeria. 8 Zamfara State, one of the Northern States of Nigeria, a predominantly Muslim populated State, was the first to begin, in the year 2000, the operation of the sharia legal system. Punitive prescriptions of the sharia system such as the cutting of limbs of a thief, separate transportation for men and women, and the poverty reduction measures for the lessprivileged in the society have apparently had little impact on the people of Zamfara State, due to the differences in the daily living experiences of Nigerian Muslims today and of the society within which the sharia prescriptions emerged. A few days ago, the Nigerian major television news bulletin (NTA Network News) reported that the Zamfara State government has resolved to enlist the help of retired armed forces and police personnel to assist in ensuring security in the state due to the incessant cases of house break- ins within the last month. This stance is further buttressed by the celebrated case of Safiya Husain, the single mother whom a Nigerian sharia court condemned to death by stoning. The decision was rescinded because of international pressure and pressure from civil rights and women’s groups in Nigeria7. Again, the intersection between religion and modern legal systems is often neglected by some conceptions of “scripture.” A relevant example is the complexities that mark the functions of the Nigerian police force, the Nigerian Law courts and the implementation of the sharia legal system in Nigeria. How scriptures functioned? “Scripture” is a normative concept that functions in fundamental ways in people’s lives. Its legitimacy in this regard often rests on its claim to divine origin and approval. “Scripture” also functions as a guiding principle for delineating social order. It offers legitimacy for social structures and provides prescriptions for social conduct all at once. “Scriptures” offer explanations for profound questions in life: Who created the world, the world of humans and the world of nature? Why death? Why do bad things happen to 9 good people? Why do bad people escape punishment and flourish? Why are there diseases? Why should a good and faithful wife die of HIV/AIDS gotten from a promiscuous husband? What of an innocent child dying from HIV/AIDS? Some “scriptures” function as tools of imperialism between and within groups. Examples of this include the alliance between the missionaries and colonial masters in colonized communities. This was true of the British colonial powers and Christian missionaries in Nigeria before 1960, where both parties cooperated to ensure the “compliance” of Nigerians to roles prescribed for them in the society. “Scripture” has also been used as a tool for indoctrination and destruction of unsuspecting and fervent worshippers; the case of the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God in Kanungu, Uganda is apposite here. In Kanungu, Uganda on the 17th of March 2000, about five hundred bodies were found burnt to death in a church. These were some members of the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God in Uganda. Further searches revealed mass graves at other sites linked to the church. According to reports, the leader of the Movement, Joseph Kibwetere, ordered the mass murder after members who had sold all their properties and donated the proceeds to the church began demanding the return of their money when the world did not end on December 31st 1999 as had been predicted. The 68-year old leader and his female assistant, Gredonia Miwerinda, however, escaped the church blaze8. Hurston--- Even the Bible was made to Suit our Imagination9. Who made the Bible? Is the Bible “scripture”? What constitutes our imagination? Who do we mean when we say “our”? Is there a collective called “our”? How may these questions impact the appreciation of the term and concept called “scriptures”? Is there a hint of approval for inculturation in this statement? By our “imagination,” is reference made to the human creativity, which in relation to “scripture” produces interpretation? In Africa, the Bible has been “domesticated” while Christianity has been under going a process of inculturation. Biblical concepts are adorned in African philosophical 10 garbs; hence references to Jesus as a kinsman, ancestor, and king are daily submissions among the people. In addition, African Christianity, a brand of Christianity with distinct features rooted in African ethos and worldview, is now recognized worldwide10. Both African conceptualizations of Jesus and African Christianity are linked with biblical hermeneutics, which could be perceived as a product of human imagination in interaction with divine endowments. However, the influence of “scripture” in this parlance is a one-way flow of influence, i. e. from the Bible to the people; there was no avenue for human lived experiences of the people to influence the “scriptures” until recently when some African women began to read the Bible alongside their daily-lived experiences11. In other words, whereas the Bible and its interpretations may influence African Biblical conceptions, African daily-lived experiences may not influence the content or structure of the Bible in any formidable manner. Wimbush---Texts are Positioned to Weave Social Textures, how they are made to form and de-form Social Identities12 The place of the “social” seems crucial in any bid to conceptualize “scripture.” Moreover, the social features both at the level of reception as well the level of constitution. The positioning of text to weave social textures would involve social engineering in a broad sense, especially as every text is a product of particular sociocultural and historical settings thus buttressing the dynamism inherent in religious experiences. This dynamic nature of religious experiences makes a constant appraisal of “scriptures” imperative. “Scriptures” as a means of forming and de-forming social identities reinforces this pertinent need. If people’s living experiences change, then 11 perceptions of such a people would also change. Further, religion constitutes an important ingredient in identity formation, especially in Africa. Social identities in Africa are formed based on religion. Similarly, these social identities may be de-formed as a consequence of religion, basically through conversion, though conversion itself is marked by multi-layered debates13. The act of forming and de-forming social identities as a consequence of religion suggests “fluidity” for the concept of “scriptures”. This “fluidity” would suggest openmindedness and the willingness for continuous assessments. The crucial place of the “social” in conceptualizing “scripture” also brings to fore the issues of politics and power dynamics. Embedded within the traditional concept of “scripture” is the power to “name” or prescribe by a minority for a majority. This points towards power distribution and utilization. Feminist concerns in religion are to a large extent geared towards addressing the imbalance that has marked power distribution in religion, especially as regards “scripture” in its constitution and interpretation. A consequence of the above discourse is that the conceptualization of “scripture” should go beyond an analysis of texts. Such an attempt should encompass socio-cultural modes such as symbols, rituals, practices, and oral narratives (folktales, myths, legends, proverbs, parables, and conventions). Eliade—“Scripture” is about--------Human Beings Shape and Reshape Themselves in Relationship to What Centering or Canonical Forces14. The study and conceptualization of “scripture” proffer a global and all-inclusive curriculum. It is an attempt that would require multidisciplinary approaches to be fruitful. However, the “canonical forces” in Eliade’s comment for the purpose of this paper may 12 prove to be a constraint. My observation bothers on the processes of arriving at a canon. Modalities and personalities involved in such an enterprise are usually particularistic and opposed to a situation where the “social” is prioritized. That humans shape and reshape themselves on the one hand and are shaped and reshaped by prevailing circumstances on the other hand confirms that “scripture” as a concept should be marked by “fluidity.” The canonization of the Bible for instance warranted the elimination of some books from the recognized list of literature in Christianity. Though the process was regulated by some identified regulations, the possible potentials of the excluded books were permanently foreclosed. The power to “name” prescribes exclusive selections by the minority based on the prevailing agenda for the group that “names” and not of the group that the naming is being formulated for. Canonization also assumes a closed scripture but this is at variance with the situation in African religions where scriptures are open-ended. The people’s encounters with other cultures reflect in the religious corpus for example. Visotzky-----If I want to know a People, I want to know what Scriptures They Read15. Just as the totality of a people’s lived experiences is recommended to be a contributing factor to forming “scriptures,” it would seem that a people’s “scripture” also serve as a tool of analysis for their identities. It appears salient that the “scripture” of a people supplies information on their social, economic, political and cultural experiences. Emanating from this submission, however, is the dynamic nature of the concept of scripture: are “scriptures” universal or exclusive or both? Would it be fair to ascribe a “scripture” to a particular people in this age of globalization? The rate of culture contact 13 and change in contemporary society is explosive: how relevant would it be for a people to lay claim to a particular “scripture”? African religions, for example, now have adherents beyond Africa, and adherents in the Diaspora have been innovative with received narratives. Would the “scriptures” of African religion in the Diaspora still be described as belonging to African people on the continent? A people’s scriptures would be an appropriate avenue to appraise and analyze the socio-cultural experiences and indeed the people’s orientations and philosophy. In African, religion would mark the right angle for analyzing the people’s disposition in all other sectors of human endeavors as religion is basic to every other sector in African communities. The process by which a people received and harnessed a particular scripture could also prove informative about the identity formation and philosophy of a people. Conclusion I have attempted to show through this response paper my subscription to the stance that the concept of “scriptures” as it presently exists in religious studies is inadequate. Some of the motifs and themes from this attempt include the essential place of fluidity in conceptualizing “scripture,” the crucial place of the “social” in the constitution of “scriptures,” the importance of the human agency and the distribution of power in arriving at “scriptures,” and the need to see “scriptures” as a means of information about a people. This paper also attempted an analysis of issues on the universal or exclusive character of “scripture” and the need for a re-appraisal of the functions of “scriptures” from the perspective of how such scriptures were received and what had been done so far with the scripture. 14 Notes and References V. Wimbush (2004) “Scriptures: Fathoming a Complex Social-Cultural Phenomenon” Discussion Paper at the International Conference Launching the Institute for Signifying Scriptures, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA, p. 4 2 L. Matory, Sex and the Empire That is No More (Minneapolis: University of Minnesoto Press, 1994). 1 3 V. Wimbush, p.4 Examples of such scriptures include: the Bible, the Quran, and the Vedas. 5 V. Wimbush, p. 6 6 V. Wimbush, p. 7 7 The case of Safiya Husain of Sokoto State, Nigeria is an example. She was convicted for adultery and a 4 rajm (stoning to death) sentence was pronounced on her. The Sharia court of Appeal, however, faulted the sentence of the Area court. Safiya was subsequently bestowed with the citizenship of Italy in Rome.” 8 www.uiowa V. Wimbush, p. 7 10 J.A. Omoyajowo, Cherubim and Seraphim: the History of an African Independent Church (New York: 9 NOK Publishers International, 1982). 11 D. Musa (ed.) (2001) Other Ways of Reading: African Women and the Bible. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, Geneva, WCC Publication. 12 13 V.Wimbush, p. 13 Shaw, R & C. Stewart (1994) “Introduction: Problematizing Syncretism” in C. Stewart R. Shaw (eds.) Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis. New York: Routledge. 14 15 V. Wimbush, p. 16 V. Wimbush, p. 24