AJC Submission.doc - News

advertisement

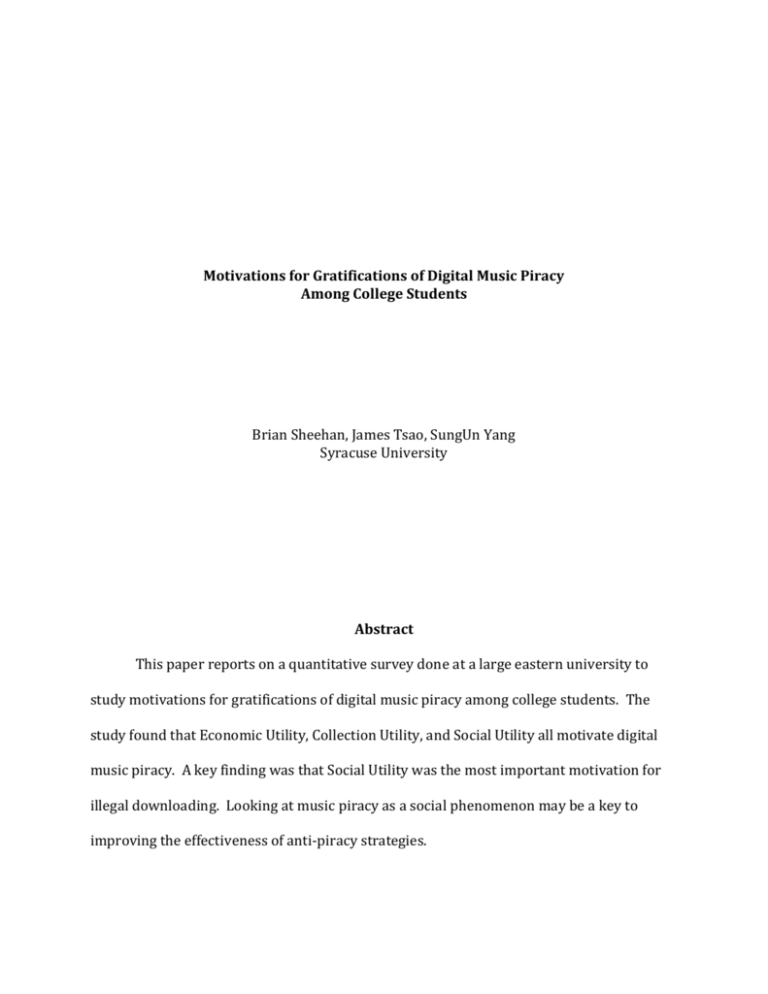

Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Brian Sheehan, James Tsao, SungUn Yang Syracuse University Abstract This paper reports on a quantitative survey done at a large eastern university to study motivations for gratifications of digital music piracy among college students. The study found that Economic Utility, Collection Utility, and Social Utility all motivate digital music piracy. A key finding was that Social Utility was the most important motivation for illegal downloading. Looking at music piracy as a social phenomenon may be a key to improving the effectiveness of anti-piracy strategies. Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Introduction Digital music piracy is a significant problem that threatens the future of the music production industry. The music industry federation estimates that 95 percent of music downloads are pirated (Pfanner, 2009). Recent estimates put the lost revenue from illegal downloading at $3.7 billion annually in the U.S. (IFPI Digital Music Report, 2008). The biggest group of downloaders is college students, who are salient for their size as a group as well as their frequency of downloading (Bott, 2006). It has been estimated that one out of three college students downloads music illegally. They are especially problematic because two-thirds of those who download do not care if the music is copyrighted or not (Richmond School of Law, 2006). This has led the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) to state that digital music piracy among college kids is “especially and disproportionately problematic” (http://riaa.com/faq.php, ¶ 31). This paper reports on the second stage of a three-stage research project to examine digital music piracy among college students. The first stage, completed in January 2009 (----------, 2009) was a qualitative research project with the goal of creating a cognitive map that would correctly identify the specific motivations for digital music piracy among college students (See Diagram 1). Further, the model aimed to identify specific factors that either reinforced or detracted from college students’ motivation to download illegally. The current stage is a quantitative research project with the goal of confirming, modifying or refuting the hypothetical cognitive map. The specific purpose of this paper is to analyze the preconditions of motivations and their relationship to gratifications for digital music piracy. The future third stage will consist of developing and testing specific advertising concepts based on the specific findings of this quantitative research. The ultimate goal will be to find 1 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students advertising concepts that are statistically significant in their ability to decrease illegal downloads and/or increase the use of legal download programs among college students. [Diagram 1 About Here] The significance of this study is directly related to the economic magnitude of the problem for the recording industry. For every illegally downloaded album there is one-fifth of a lost sale (Bott, 2006). The billions of dollars being lost by illegal behavior has significantly impacted the music industry and affected the economic livelihood of both established and rising artists. Additionally, there is a societal cost when many citizens flout the law. Our project has the potential to help the industry reclaim revenue that is rightly and legally theirs and to decrease the societal cost of group lawbreaking. Review of Literature Listening to digital music is an essential part of the college lifestyle (-----------, 2009). As students from a variety of ethnic, social, and economic backgrounds assimilate into a new, shared learning environment, music becomes an important social agent that leads to the forming of new norms. One of those norms is digital music piracy. Beyond its economic impact on the music industry, digital music piracy may have significant social costs, including a widespread moral relativism that makes frequent flouting of society’s inconvenient laws acceptable. Both Uses and Gratifications and Social Cognitive Theory may be suitable frameworks for interpreting this behavior. Specific psychological aspects of college-aged students that influence their social behavior must also be considered. Previous studies of digital music downloading and similar behavior, such as file sharing of motion pictures, should also be reviewed. Uses and Gratifications At its most basic level, illegal downloading behavior can be described from a Uses and Gratifications (U&G) perspective. U&G emphasizes that people are in control of their 2 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students usage and their relationships with various media. A medium’s ability to meet a person’s needs, or gratifications sought, including their desires for escapism, personal relationships, personal identity, and surveillance of the world around them, will dictate whether a person uses that specific medium (Blumler and Katz, 1974). But what of a medium that is used illegally? In the 1950s, Schramm (cited in Baran & Davis, 2006) devised what he called the fraction of selection to show how people choose media. He claimed that people weigh the level of reward that they expect from a medium or message against the effort that they have to make in order to get that message. For music downloads, people weigh the instant gratification of getting the music they want against the effort of going online and logging on to their file-sharing software. In this case the gratification is enhanced by the fact that multiple files can be downloaded each time the medium is used. For illegally downloaded music, it can be surmised that any fear, guilt, or cost of being caught is factored in as well. U&G theory has been resurgent with the growth of the Internet. The interactive nature of the Internet underscores the power of choice each individual has over the media they choose to use and how they choose to use it. Asynchroneity, defined as the ability to send and receive messages at the users’ convenience (Chamberlain, 1994), is what allows individuals to take greater control of interactive media. This includes the potential to send and receive content that skirts the legal requirements to pay money for copyrighted content. U&G has been empirically studied for more than three decades, providing a strong foundational framework for examining music downloading behavior. The behavior of music downloaders is undeniably proactive and choiceful, especially when downloading illegally. 3 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Social Cognitive Theory Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) posits that when a specific behavior has a positive outcome it is likely to lead to a repeat of that behavior. Similarly, a negative outcome would likely lead to a reduction or elimination of that behavior. An important aspect of SCT is that it suggests that positive or negative outcomes do not need to be personally experienced to be personally determined. They can be determined through social observation. In other words, a person can determine potential outcomes either by personal experience or by observing the experience of others (Bandura, 1977). As a specific example in relation to music piracy, if college student “A” illegally downloads an album and realizes a significant cost savings, it will increase the likelihood of college student “A” illegally downloading music in the future. On the other hand, if college student “A” has a close friend (college student “B”) who is caught and fined for illegal downloading, it will decrease the likelihood of student “A” illegally downloading music in the future. SCT is specifically useful for examining factors that either increase or decrease the perceived positive or negative outcomes of any behavior. Regarding anti-music piracy advertising, for example, SCT helps us look at the ability of advertising messages to increase perceptions of personal risk and perceptions of socially-observed risk. Psychological Aspects of College Students Reasons for the high level of music piracy among college students are both behavioral and psychological. Age is directly related to increased music piracy (Bhattacharjee, Gopal & Sanders, 2003). Behaviorally, college students spend more time with the Internet than any other medium. Over 30% of college students spend at least ten hours on the Internet, while 20% spend twenty hours or more. (Burst Research, 2007) Psychologically, there are a number of specific 4 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students aspects of college-aged students’ mindset that are relevant to music piracy, including risk-taking, sensation seeking, optimistic bias and anti-industry bias. There is evidence that risk taking is related to age (i.e., younger people take more risks than older people). Young people take risks in order to gain “varied, novel, complex or intense experiences” (Zuckerman, 1994, p.27). The risks can be social, physical, legal or financial (Zuckerman, 1979). As an example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in their National College Health Risk Behavior Survey, found that college students frequently engaged in risky behavior, while those over 25 were less likely to drink and drive. Weisskirch & Murphy (2004), in a study of college students’ behaviors and attitudes toward Internet activities, found higher levels of sensation seeking specifically for students who used the Internet to download music, to obtain sexual content, and/or to send instant messages. Risk taking is also socially related. James (1997) noted in his research that a common excuse for breaking the law was that respondents felt they were just doing what everybody else was doing. Looking at this same phenomenon from another angle, research respondents consistently under-reported personal behaviors that they deemed to be socially undesirable and over-reported behaviors that they saw as socially desirable (Raghubir & Menon, 1996). This is termed social desirability bias. Interestingly, with over 50% of students readily admitting to illegal music downloads, there is the indication of a large degree of social acceptance for the behavior (i.e., it may not be deemed to be socially undesirable by a large segment of the student population). Further, we can assume that if there were no legal risk associated with admitting to the behavior, the percentage of those admitting to the behavior would be even higher. The social desirability bias for illegal downloading among college students is, therefore, surprisingly low. High degrees of risk-taking may be, in part, an outcome of the penchant for college-aged students to have high degrees of optimistic bias. Individuals, in general, are challenged to 5 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students compare their individual risk with the risk to others (Weinstein, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987). According to Chapin (2000), “individuals believe they are less vulnerable to risks than others” (p. 52). Assessment of risk is essentially egocentric. Optimistic bias is especially pronounced among youth. This is in large part because risk perception is related to a combination of cognitive development and collected experiences (Weinstein, 1989). College-aged students are particularly limited in their collected experiences as opposed to older comparison groups. Youthoriented optimistic bias was demonstrated in a study of urban minority at-risk students, which found that an overwhelming majority (89%) felt a degree of optimistic bias toward their risk of contracting HIV infection despite clear evidence to the contrary (Chapin, 2000). Optimistic bias increases “third-person perception.” With specific regard to communications, third-person perception means that people believe communications have a greater affect on others than on themselves (Davidson, 1983). Another factor related to illegal downloading by college students is anti-industry bias. Research has shown that, when there is a perceived inequitable relationship between the music copyright holder and the individual, negative attitudes toward music piracy tend to soften (Kwong & Lee, 2002). Perceptions of an inequitable relationship regarding music ownership result in both anti-industry feelings, against music companies, and anti-artist feelings. Lack of exposure to the corporate world and media-driven images of opulent music star lifestyles may be reinforcing lax attitudes toward music piracy among college students. Importantly, they may also be allaying any feelings of guilt. The specific psychology of college-aged students offers a mix of high degrees of risktaking and sensation seeking, fueled by optimistic bias, and reinforced by anti-industry/anti-artist bias. This mélange reinforces their desires to download illegally and minimizes moral dilemmas. 6 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Gopal, Sanders, Battacharjee, Agrawal & Wagner (2004) found that swapping online music had a negative correlation to ethical and moral dispositions. Research on File Sharing of Motion Pictures A recent study on file sharing of motion pictures maps out six specific user utilities (Hennig-Thurau, Henning & Sattler, 2007). Given the similarities of illegal music downloading and illegal movie file sharing behavior, these utilities may be relevant to our study. The six specific utilities observed for movie piracy were: 1) Transaction Utility (the ability to get a “better deal”); 2) Mobility Utility (the ability to store on mobile devices, like iPods); 3) Storage Utility (not having to acquire a physical copy); 4) Anti-industry Utility (related to anti-industry bias, generated by perceptions of greedy movie corporations); 5) Social Utility (the ability to increase social connections and peer interactions via the illegal movie copies) and 6) Collection Utility (the ability to collect a large amount of movies regardless of financial status). The study found that two particular utilities—anti-industry utility and collection utility—significantly enhanced users’ experiences of attaining pirated movies. The study of Hennig-Thurau, et. al. (2007) found that there were also costs associated with the attainment of pirated movies that could mitigate users’ levels of utility. Of the four specific costs identified, three were perceptual costs. In other words, the costs were based on the subjective perceptions of risk or guilt by the downloader at the time of the download. These costs were: 1) Technical Costs (e.g., perceived risk of computer viruses or bad files); 2) Legal Costs (e.g., perceived risk of fines or penalties); and 3) Moral Costs (e.g., concerns about stealing). As seen in earlier research on optimistic bias, if the optimistic bias is high, technical and legal costs would likely be perceived to be relatively low. As seen in previous research on social desirability bias, if social acceptance of illegal movie file sharing is high, then moral costs 7 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students would also be perceived to be quite low. The one true or hard cost was the search cost (i.e., the actual time spent searching for the illegal copy). The utilities outlined for digital movie piracy may provide a strong construct for the study of digital music piracy. Specifically, we will look at the utilities and benefits of digital music piracy for users to see if they are the same or similar to those of digital movie piracy. We also have particular interest in whether the costs that act as a potential brake on the illegal behavior are real or perceptual at the time of the actual download. Understanding utilities, benefits, and perceived costs will help us better understand what kinds of messaging can impact them most directly. Previous Music Downloading Research Rochelandet & Le Guel (2005) found that music downloaders prefer illegal copies to legal copies when they offer greater utility. They found that perceptions of utility were influenced by three factors: 1) the ability to substitute one for another; 2) the costs associated with the legal copy; and 3) the net utility of buying the original (i.e., the benefits minus the purchase costs). Chiou, Huang & Lee (2005) found that illegal downloading behavior was a function of a user’s satisfaction in relation to their perceptions of prosecution risk and overall magnitude of consequence. Their perception of the social consensus was equally important. These studies support the need to build a clear, comprehensive model to explain the utilities, benefits, and costs of music piracy to downloaders. Sinha & Mandel (2008) showed that definitions of benefits and costs are not so clear-cut when related to illegal behavior. They found that negative consequences of digital music piracy may increase the behavior among some downloaders as well as decrease it among others. They note that a person’s optimum stimulation level (OSL) determines their piracy potential (Raju, 1980): the higher the OSL, the higher the willingness to take risks to achieve the desired 8 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students sensations (Zucherman, 1979). Because college students have a heightened desire for sensation seeking, and therefore high OSL, increasing perceived costs could have a boomerang effect. Specifically, increasing the perception of risk could create a heightened sense of sensation. These results are consistent with findings regarding the National Youth Anti-drug Media Campaign. The campaign’s primary purpose was to prevent the initiation of drug use by 9-18 year olds. After spending almost $1 billion over six years, the results were disappointing. The campaign “may have been showing unintended boomerang effects on its youth audience, such that, over time, those who had greater exposure to campaign messages were more likely to demonstrate pro-drug outcomes….” (Jacobsohn, 2007, p.1). The literature paints a picture of college students who are willing to take risks by using illegal music downloads to gain specific utilities and gratifications. Students judge the specific amount of risk by weighing the level of gratification versus specific perceived costs. Further, attitudes such as Anti-musician/Anti-music industry bias and feelings of optimistic bias may increase the possibility of the behavior by either enhancing the gratification or lowering the perceived costs. Previous literature provide a general framework of music piracy behaviors, but it needs more empirical research to build a well-defined practical model that helps the industry understand the issue and develop effective strategies to stop digital music piracy. As such, the following section includes hypotheses and research questions designed to be exploratory on the relationship between variables. Hypotheses and Research Questions Digital music piracy is commonplace on college campuses (Richmond School of Law, 2006). Social Cognitive Theory suggests that positive outcomes and observations motivate repeated behavior (Bandura, 1977). Colleges are unique environments that combine tightknit peer social groups, the psychology of youth, and economic factors of low disposable 9 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students income. Any or all of these factors could be enhancing the perception of positive outcomes of music piracy for college students that lead to repeated music piracy. Our previous qualitative study (-------------, 2009) indicated specifically that Economic Utility, Collection Utility, and Social Utility were primary motivations. This leads us to ask: RQ1: What are specific motivations for digital music piracy among college students? Existing research has indicated that a number of attitudes exist among youth, in general, and in specific relation to illegal music downloading that have the potential to reinforce illegal music downloading behavior. Examples are Optimistic Bias (Weinstein, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987, 1989; Chapin 2000), Anti-musician/Anti-music Industry Bias (Kwong & Lee, 2002). Further, our previous qualitative research indicated that peer group social acceptance of the behavior was also a reinforcement. This leads us to hypothesize that: H1: There is a statistical relationship between specific reinforcements and motivations for digital music piracy. Existing research on both digital music and movie piracy indicate that there are specific costs associated with the behavior (Hennig-Thurau, Henning & Sattler, 2007; Rochelandet & Le Guel, 2005). Our previous qualitative research indicated that Technical Cost and Legal Cost had the potential to act as reverse reinforcements on the behavior. This leads us to hypothesize that: H2: There is a statistical relationship between specific perceived costs and motivations for digital music piracy. Uses and Gratifications Theory indicates that people use specific media for specific gratifications (Blumler & Katz, 1974). Different motivations, therefore, should have 10 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students different levels of importance for generating specific gratifications that lead to the behavior. This leads us to hypothesize that: H3: Different motivations to download music illegally could predict the extent to which the gratification of digital music piracy is reached. Method Samples The convenience samples of the study included two-hundred and four college students who voluntarily participated in an anonymous survey in February 2009. The majority of the survey participants were recruited from four undergraduate classes and one graduate class in a large university on the east coast of the United States. The respondents were asked to fill out a questionnaire that took approximately 15 minutes to complete. The survey used a filter question, “How often do you download music using an illegal program?” to select qualified samples. Answers to the question were measured on a five-point scale ranging from “Never,” “Rarely,” “Sometime,” “Often,” to “Always.” Responses to the question with “Never” were excluded for analysis. In the end, data of 153 samples were analyzed in the study. Table 1 provides demographic profile of the samples. Convenience sampling, as used in this study, depends on readily accessible participants to provide exploratory findings. Generally, data collected from nonprobability sampling are problematic because they are short of representations of the large populations. However, collecting available data to explore hidden relationships among variables has been widely acceptable in social science research (Baxter and Babbie, 2004). A similar sampling method was used in previous studies including Chiou, Huang & Lee (2005) and LaRose, Rai, Lange, Love, and Wu (2005). The sampling size of the current study is thought to be adequate for the purpose of multivariate analysis (Garson, 2009). 11 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students [Table 1 About Here] Questionnaire The survey questionnaire included 59 questions developed with reference to the studies of Hennig-Thurau, Henning & Sattler (2007), Rochelandet & Le Guel (2005), and the authors’ previous qualitative study on this subject (--------------, 09). The cover letter and questionnaire were pre-tested in a small focus group including four undergraduate students. Definitions of variables Motivations for digital music piracy: Different reasons why respondents took the risk and were engaged in the illegal music downlading. Reinforcements: Internal and external perceptions that help illegal downloaders to justify their motivation to download music illegally. Perceived costs: Both tangible and intangible costs that downloaders associate with illegal music downloading. Gratification of digital music piracy: Feelings of personal satisfaction and accomplishment after downloading music illegally. Operations of variables Multiple regression analyses were conducted to test three hypotheses. Motivations for Digital Music Piracy was the dependent variable measured in H1 and H2. The variable included a group of nine questions measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” “strongly agree.” There were two separate independent variables, Reinforcements and Perceived Costs, for the measurement of H1 and H2. Reinforcements included responses to 17 questions that were factor 12 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students analyzed. The questions were designed according to the qualitative research previously conducted by the authors and the research of Hennig-Thurau, Henning & Sattler (2007), Rochelandet & Le Guel (2005). To measure H3, responses to the nine questions were reduced into three factors, Collection Utility, Economic Utility, and Social Utility. (Details of the three factors are explained in the section of Results.) The dependent variable of H3 was a composite variable of feeling a sense of reward and accomplishment from digital music piracy (r=.34; p< .001). Results RQ1: What are specific motivations for digital music piracy among college students? A principal component factor analysis with Varimax rotations was conducted to identify different motivations for digital music piracy among college students. Table 2 shows that nine variables submitted to the factor analysis yielded three main motivations, Economic utility (Eigenvalues= 3.49; Percent of variance= 38.82), Collection utility (Eigenvalues= 1.42; Percent of variance= 15.79), and Social utility (Eigenvalues= 1.14; Percent of variance= 12.66). Economic utility and collection utility, as motivations of digital music piracy, are unsurprising because they are consistent with previous findings (HennigThurau, Henning & Sattler, 2007). Social Utility as the third motivation is a crucial finding. It adds a new dimension to the study of motivations for digital music piracy. It opens up the possibility that, for college students, the perceptions of positive or negative outcomes, as theorized by Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), may be constructed by the opinions of peers as well as personal experience and observation of the experiences of others. The three factors as motivations confirmed the conceptual model proposed in the earlier qualitative study. [Table 2 About Here] 13 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students H1: There is a statistical relationship between specific reinforcements and motivations for digital music piracy. Before testing H1, we conducted a factor analysis and identified four underlying commonalities among fifteen variables considered to be reinforcements to the motivation for digital music piracy (see Table 3). The four underlying commonalities were Moral Conscience (Eigenvalues= 3.60; Percent of variance= 23.98), Anti-musician/Anti-music Industry (Eigenvalues= 1.62; Percent of variance= 10.79), Social Acceptance (Eigenvalues= 1.53; Percent of variance= 10.23), and Optimistic Bias (Eigenvalues= 1.21; Percent of variance= 8.06). [Table 3 About Here] Moral Conscience represents an internally driven value that might deter students from engaging in digital music piracy. There was a subconscious sentiment of Antimusician/Anti-music Industry bias among students. Respondents did not really believe that illegal music downloading would hurt music artists and/or the music industry. Our previous qualitative findings indicated this is because they perceived the industry and most recoding artists to be very wealthy, making them biased against the industry/artists where money matters were concerned, but not in general (-----------, 2009). Social Acceptance represents an externally driven perception. Illegal music downloading might be attributed to perceived peer behavior. In other words, respondents thought everyone else was doing it, so it was okay for them to do. Optimistic bias provides the notion that respondents continued to download music because they believed they were luckier, or smarter, than those people who got caught. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the first hypothesis (See Table 4). The dependent variable, Motivation to Engage In Digital Music Piracy, was a composite 14 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students variable from the factors of Economic Utility, Collection Utility, and Social Utility. The independent variables were the four reinforcements including Moral Conscience, Anti Musicians/Anti-music Industry, Social Acceptance, and Optimistic Bias (R= .51, R-Square= .26, d.f.= 4, F= 11.58, p< 0.001). The results show that low value of moral conscience led to a stronger motivation to download music illegally (Beta= -0.27; t= -3.63; p< .001). Greater acceptance of music piracy as a social norm (Beta= 0.24; t= 3.26; p= .001), higher levels of optimistic bias (Beta= 0.19; t= 2.47; p< .05), and sentiments against the music industry (Beta= 0.30; t= 3.99; p< .001), also led to stronger motivations to illegally download music. H1 was supported since all four independent variables yielded significant results. [Table 4 About Here] H2: There is a statistical relationship between specific perceived costs and motivations for digital music piracy. The independent variables were three different types of perceived costs: Search Cost, Technical Cost, and Legal Cost. Search Cost was a single-question variable. The survey provided the statement, “The process of obtaining music illegally is easier than the legal process.” The responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Technical cost was an aggregated variable combined from two different variables, “fear of virus” and “fear of losing my Internet privileges” deter me from using illegal music downloading programs (r= .40; p< .001). Legal cost was a single factor generated from six variables related to legal issues that deter respondents from using illegal music downloading (Eigenvalues= 2.89; Percent of variance= 48.08; Alpha= .82; Mean= 3.13). These six variables represented both fear of, and knowledge of, legal cost. The variables included 1) “news stories about the consequences,” 2) “personal stories told by peers about the consequences,” 3) “legal actions taken by colleges and 15 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students authorities,” 4) “fear of large monetary fines,” 5) “fear of University punishment,” and 6) “think of negative implications.” Testing H2 (See Table 5), we conducted a multiple regression analysis and measured if the Search, Technical, and Legal costs could explain the dependent variable, Motivation to Engage In Digital Music Piracy (R= .28, R-Square= .08, d.f.= 140, F= 4.078, p< .01). The results show that Search (Beta= 0.18; t= 2.11; p< .05) and Technical Costs (Beta= 0.19; t= 2.09; p< .05) significantly predicted the motivation to illegally download music, but Legal Cost did not reach the statistical significance (Beta= -0.16; t= -1.8; p= .07). This result regarding Legal cost may be consistent with the earlier indications of optimistic bias. Because college students observed that few people were ever fined for illegal downloads, it might not be seen as a significant cost. Since two of three independent variables could significantly explain the digital music piracy, H2 was mostly supported. [Table 5 About Here] H3: Different motivations to download music illegally could predict extent to which the gratification of digital music piracy is reached. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the hypothesis. Gratifications, as the dependent variable, represented the feelings of reward and accomplished actions of digital music piracy. Table 6 shows that the three main motivations, Collection Utility, Economic Utility, and Social Utility positively and significantly predicted the gratifications of digital music piracy (R= .46, R-Square= .22 d.f.= 141, F= 12.97; p < .001). The higher the degree of motivation for Economic (Beta= 0.15; t= 2.04; p< .05), Collection (Beta= 0.30; t= 4.0; p< .001), and Social Utility (Beta= 0.32; t= 4.33; p< .001), the greater extent to which gratification was reached. Among the three motivations, Social Utility contributed the highest level of gratifications; Collection Utility, the second, closely followed by Economic 16 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Utility, according to the individual beta weight that each motivation received in the equation. Therefore, H3 was supported. [Table 6 About Here] Discussion The quantitative results confirmed the model generated by our previous qualitative analysis. Specifically, it confirmed that Economic, Collection, and Social Utilities all motivate digital music piracy. In some aspects, this was unsurprising. The Economic and Collection Utilities of digital piracy are somewhat obvious, and have been revealed in previous studies of both movie and music piracy (Hennig-Thurau, Henning & Sattler, 2007; Rochelandet & Le Guel, 2005). The importance of Social Utility was an important new finding, however. This finding may support music piracy as an aspect of social network theory (Kadushin, 2003), which underscores the importance of social connections and relationships in regard to individual actions. The importance of social networks, in part, explains the spectacular rise of music sharing and social networking websites, such as Facebook, on college campuses. While our previous qualitative results led us to believe that Social Utility was an important motivator, our quantitative results showed that it contributed more to the level of gratification than Economic Utility. Going into the research, our hunch was that Economic Utility would be dominant, followed by the other two. We felt it only natural to assume that the free nature of the product was by far the most important motivator. The fact that Social Utility was the most important motivation for illegal downloading was a big surprise. Collection Utility as the second most important motivation, ahead of Economic Utility, was also a surprise. When looking at the specific factors that reinforced the motivations to download, we found that previously documented anti-musician/anti-music industry feelings and feelings 17 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students of optimistic bias were clearly present (Weinstein, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1987, 1989; Chapin, 2000; Davidson, 1983; Kwong & Lee, 2002). Again, the most significant findings were related to the influence of social aspects. Higher levels of social acceptance led to stronger motivations to illegally download. Another reinforcement, moral conscience, gave a previously researched result: when moral conscience was low, desire to illegally download is high (Gopal, Sanders, Battecharjee, Agrawal & Wagner, 2004). With an understanding of the importance of social acceptance, however, we can look at this result in a different way. Rather than being an absolute measure of moral conscience (i.e., right versus wrong), if we look at this through the social lens, we can see it more as a measure of what is deemed socially acceptable or unacceptable. We see this clearly in respondents’ reactions to statements to survey questions such as: “I never consider illegally downloading music as stealing,” and “Downloading music illegally doesn’t bother me at all.” In an atmosphere of strong peer social acceptance of illegal music downloading behavior, positive answers to statements like these were probably not seen by college students as morally worrisome in any discernable way. Indeed, morality is in the eye of the beholder, or the beholder’s social group. More surprises awaited us in the analysis of cost factors that had the potential to act as brakes—or reverse reinforcements—to the illegal behavior. Again, some results were expected based on previous research. Search costs and technical costs were inversely related to the motivations. Surprisingly, legal costs were not related at all. Research on illegal music file sharing by Hennig-Thurau, Henning & Sattler (2007) had led us to believe that legal costs would be positively correlated. The observed lack of positive correlation can possibly be explained by our previous qualitative research findings (--------, 09). In personal and group interviews, the legal cost for downloading using on-campus servers was seen as extremely high. 18 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Most respondents had a friend, or had heard of someone, who had been caught and/or fined. Off campus, in the “real world,” however, respondents indicated that their fear of being caught was infinitesimally small. With such a low perceived possibility of being caught, it is reasonable to theorize that the optimistic bias of college kids regarding legal costs grew to such an extent that legal costs no longer had the potential to act as a brake on illegal behavior. This observation of the ineffectiveness of legal strategies may explain why the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), after initiating over 35,000 lawsuits since 2002, indicated in December 2008 that it would significantly decrease new lawsuits in general and stop suing individual for unauthorized music sharing. Along similar lines, Apple’s CEO, Steve Jobs, recently called for the music industry to drop digital rights management (DRM) software, which prevents people from sharing the music they legally download. Our findings are summarized in a revised, quantitatively based cognitive map (Diagram 2). [Diagram 2 About Here] Implications The findings of this study have strong implications for the music industry and how they fight the problem of college music piracy. One key implication is that the industry should not only be developing strategies to fight individual downloaders, as a focus on individual lawsuits does. Rather, they should perceive the problem as fundamentally social. This indicates that grass roots efforts within colleges that focus on times when students are assembled either physically or in social networks could prove effective. In terms of broader communication, messages with the objective of overturning peer group social acceptance by showing the cost of the behavior on the peer group, its image or society at large might be more effective than focus on individual risks. Another key implication is that, in addition to social strategies, any program, 19 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students legal approach or advertising campaign aiming to increase the perception of personal risk needs to reframe the perception of risk substantially. Aside from using on-campus servers, the perception of personal risk to college students is, today, very small. A swift and drastic shift in perception would be important not just on an individual basis, but because it could create a social tipping point among college peers. A key to combining personal and social costs might be to focus on things related to music piracy that could cause extreme personal embarrassment within the insular social peer networks of college campuses. Limitations The study took place on the campus of a large, private eastern university. Chiou, Huang & Lee’s (2005) research implies that behavior related to music piracy may vary across different college campuses. Differences in environmental and social factors mean that solutions that work on one campus may not work on others. More studies of a similar nature would need to be done in other regions and at different sized universities with different socioeconomic make-ups. Future Research This is the second stage of a three-stage research study. The goal of the third stage will be to use the information from the first two stages to improve the effectiveness of communications programs intended to convince college students to stop downloading illegally. To date, it is unclear whether communications to college students have had any effect in modifying their behavior. We will test a variety of new communications approaches versus existing approaches experimentally. Another area for further study would be to study the concept of embarrassment within college peer networks to determine how some social behaviors can be transformed from acceptable to embarrassing. Finally, our qualitative results indicated that a vast majority of 20 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students college students considered themselves “light downloaders,” regardless of how many illegal songs they had downloaded. Students who downloaded over 100 songs a year illegally believed they didn’t download enough to be a problem. This was not borne out in the quantitative results, but is worth further investigation because finding ways to change such a perception, if it exists, could help decrease digital music piracy. References ------------- (2009). Improving the Effectiveness of Anti-Digital Music Piracy Advertising to College Students. Submitted to journal for review. Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Baran, S.J. & Davis, D.K. (2006). Mass communication theory: Foundations, ferment, and future (2nd Ed). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. Baxter, L. A. & Babbie E. (2004) The Basics of Communication Research. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. Bhattacharjee, S., Gopal, R. D., & Sanders, G. L. (2003). Digital music and online sharing: Software piracy 2.0? Considering the similarities and unique characteristics of online file sharing and software piracy. Communications of the ACM, 46 (7), 107-111. Bott, M. (April 13, 2006). Study examines student download habits. The California Aggie. Blumler, J.G., & Katz, E (1974). The uses of mass communications: current perspectives on gratifications research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1997). National college health risk behavior survey. Cited in M. Rolison, A. Scherman, College student risk-taking from three perspectives (2003). Adolescences, 38. 21 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Chamberlain, M. A. (1994). New technologies in health communication. American Behavioral Scientist, 38, 271-284. Chapin, J. (2000). Third-person perception and optimistic bias among urban minority at-risk youth. Communication Research, 27 (1), 51-81. Chiou, J., Huang, C., & Lee, H. (2005). The antecedents of music piracy attitudes and intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 57 (2), 161-174. Collins, I. (December 21, 2008). RIAA dropped lawsuits against music pirates. Retrieved January 2, 2009 from http://www.efluxmedia.com/news_RIAA_Dropped_ Lawsuits_Against_ Music_Pirates_31867.html Davidson, W. (1983). The third-person effect in communication. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47, 1-15. Garson, D. G. (2009). Multiple regression: How big a sample size do I need to do multiple regression? Retrieved June 27, 2009 from http://faculty.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/PA765/regress.htm#samplesize. Gopal, R.D., Sanders, G.L., Bhattacharjee, S., Agrawal, M., & Wagner, S.C. (2004). A behavior model of digital music piracy. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 14 (2), 89-105. Hennig-Thurau, T., Henning, V., & Sattler, H. (2007). Consumer file sharing of motion pictures. Journal of Marketing, 71 (3), 1-18. IFPI digital music report, 2008: Revolution, innovation, responsibility. Retrieved December 27, 2008 from: http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/DMR2008.pdf Jacobsohn, L. (2007). The role of positive outcome expectancies in boomerang effects of the National Youth Antidrug media campaign. Conference papers: International Communications Association, 2007 annual meeting. 22 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students James, L. (1997). Principles of driving psychology. DrDriving.org. Retrieved January 26, 2008 from http://www.drdriving.org/articles/principles.htm Kadushin, C. (February, 17, 2004). Introduction to social network theory: Chapter 2. Some basic network concepts and propositions. Retreived March 23, 2009 from http://home. earthlink.net/~ckadushin/Texts/Basic%20Network%20Concepts.pdf Kwong, T., & Lee, M. (2002). Behavioral intention model for the exchange mode internet music piracy," hicss, p. 191, 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS'02)-Volume 7. La Ferle, C., Edwards, S.M., & Lee, W. (2000). Teens use of traditional media and the Internet. Journal of Advertising Research, 40 (3), 55-65. Larose, R., Lai, Y-J., Lange, R., Love, B., & Wu, Y (2005). Sharing or piracy? An exploration of downloading behavior. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(1). Retrieved January 5, 2010 from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue1/larose.html. Pfanner, E. (April 17, 2009). Four Convicted in Sweden in Internet Piracy Case. The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2010 from http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/18/business/ global/ 18pirate.html. Raghubir, P. & Menon, G. (October, 1996). Asking sensitive questions: The effects of type of referent and frequency wording in counterbiasing methods. Psychology & Marketing, 13, 7. Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) website. For students doing reports. Retrieved January 5, 2009 from http://riaa.com/faq.php. Richmond School of Law (April 5, 2006). Intellectual Property Institute survey: One in three college students illegally downloads music. Retrieved September 16, 2008 from http://law.richmond.edu /news /view.php?item=187.. 23 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Rochelandet, F., & Le Guel, F. (2005). P2P music sharing networks: Why the legal fight against copiers may be inefficient. Review of Economic Research on Copyright Issues, 2 (2), 6982. Sinha, R.K., & Mandel, N. (2008). Preventing digital music piracy: The carrot or the stick? Journal of Marketing, 72 (1), 1-15. Weinstein, N. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 806-820. Weinstein, N. (1982). Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 5, 441-460. Weinstein, N. (1983). Reducing unrealistic optimism about illness susceptibility. Health Psychology, 2, 11-20. Weinstein, N. (1987). Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems: Conclusions from a community-wide sample. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 10 (5), 481-500. Weinstein, N. (1989). Perceptions of personal susceptibility to harm. In V. Mays, G. Albee, & F. Schneider (Eds.), Psychological approaches to the primary prevention of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (pp. 142-167). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Weisskirch, R.S., & Murphy, L.C. (2004). Friends, porn, and punk: Sensation seeking in personal relationships, Internet activities, and music preference among college students. Adolescence, 39, 189-200. Wimmer, R. D. & Dominick, J. R. (2003). Mass Media Research, 2nd ed., Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing. Zuckerman, M. (1979). Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 24 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Zuckerman, M. (1988). Behavior and biology: Research on sensation seeking and reactions to the media. In L. Donohew, H. E. Sypher, & E.T. Higgins (Eds.), Communications, social cognition, and affect (pp. 173-194). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erblaum. Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expression and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press. 25 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Diagram 1: Cognitive Map of Digital Music Piracy Reinforcements Motivations Perceived Costs 26 Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Table 1 Demographic Background of Respondents Age Frequency 27 39 26 36 14 8 150 Percent 18 26 17 24 9 5 100 Female Male 117 32 149 79 22 101 White/Caucasian Black/African American Asian/Pacific Islander Hispanic/Latino Other Total 118 3 15 9 5 150 79 2 10 6 3 100 87 59 146 60 40 100 $0-40 $41-80 $81-120 $121-160 $161-200 $201-240 $241+ 80 29 20 5 3 3 5 145 55 20 14 3 2 2 3 100 Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Graduate 44 31 28 36 10 149 30 21 19 24 7 100 18 19 20 21 22 23 or older Total Sex Total Race Residence On-Campus Off-Campus Total Income (Weekly) Total Year in College Total 27 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Table 2 Motivations for Digital Music Piracy F1: Economic Utility (Alpha= .85; Mean= 4.06) Illegally downloading music saves money. I am not making enough money to buy music. Paying for music is too expensive. F2: Collection Utility (Alpha= .70; Mean= 3.64) I can find any song and download it online. I download music with illegal program because I feel like everything I want is right at my fingertips. F3: Social Utility (Alpha= .64; Mean= 3.53) Downloading is all about sharing songs with friends. It is enjoyable to see what other people have in their collection… F1 0.72 0.88 0.91 F2 0.33 0.17 0.14 F3 0.15 0.02 0.08 0.14 0.13 0.83 0.82 0.13 0.07 0.00 0.06 0.21 0.00 0.77 0.87 Eigenvalues Variance explained (%) 3.49 38.82 1.42 15.79 1.14 12.66 Table 3 Factors of Reinforcement to Motivate Digital Music Piracy F1: Moral Conscience (Alpha= .77; Mean=2.87) I don't think twice when illegally downloading music (r). Downloading music illegally does not bother me at all (r). I never consider illegally music downloading as stealing (r). I believe there is a chance that I will get caught when I illegally download music. F2: Anti-musicians/music industry (Alpha= .63; Mean=2.81) There are bigger issues record companies and musicians should worry about other than illegal music downloading. Illegal music downloading hurts artist and others who work in the music industry. Musicians and record companies make so much money that downloading music illegally cannot hurt them (r). F3: Social Acceptance (Alpha= .50; Mean=2.89) Downloading music illegally is acceptable because it is unlike other more risky illegal behaviors that might physically harm people. I download music illegally because everybody does it. F4: Optimistic Bias (Alpha= .53; Mean=2.92) I try to use illegal programs that are more difficult to track when illegally download music. I think I am luckier than other downloaders who get caught. Eigenvalues Variance explained (%) 28 F1 0.89 0.87 0.57 F2 -.10 -.13 -.39 F3 0.92 -.21 -.35 F4 0.16 0.6 0.25 0.54 0.01 0.14 -.07 -.19 0.69 0.08 0.13 -.13 0.66 -.04 -.07 -.16 0.75 .05 -.02 0.08 -0.03 0.30 -.16 0.73 0.77 -.06 0.16 0.11 -0.03 0.13 -0.09 -.02 0.18 0.80 0.77 3.60 23.98 1.62 10.79 1.53 10.23 1.21 8.06 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Table 4 Multiple Regression Analysis of Reinforcements on Motivations of Digital Music Piracy Reinforcements Moral Conscience Anti Musicians Social Acceptance Optimistic Bias B -0.47 0.52 0.42 0.32 ß -0.27 0.30 0.24 0.19 t -3.63 3.99 3.26 2.47 Sig. < 0.001 < 0.001 0.001 <.05 R = .51, R-Square = .26, d.f. = .4, F = 11.58, p < 0.001 Table 5 Multiple Regression Analysis of Perceived Costs on Motivations of Digital Music Piracy Perceived Costs Search Cost Legal Cost Technical Cost B 0.28 -0.28 0.17 ß 0.18 -0.16 0.19 t 2.11 -1.80 2.09 Sig. < .05 0.07 < .05 R = .28, R-Square = .08, d.f. = 140, F = 4.078, p < .01 Table 6 Multiple Regression Analysis of Motivations on Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Motivations Collection Economic Social B 0.50 0.25 0.54 R = .46, R-Square = .22 d.f. = 141, F = 12.97 p < .001 29 ß 0.30 0.15 0.32 t 4.00 2.04 4.33 Sig. < 0.001 < .05 < 0.001 Motivations for Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Among College Students Diagram 2: Summarized Findings of Digital Music Piracy Reinforcements Moral Conscience Anti musicians Social Acceptance Optimistic Bias (-)** (+)** (+)** (+)** Motivations Social (+)** Collection (+)** Economic (+)* Perceived Costs Search (+) * Legal (-) (ns) Technical (+) * * P< .05 ** P< .001 A “+” sign represents a positive relationship between the two variables. A “-“ sign represents an inverse relationship between the two variables. “NS” means that there is no relationship between the two variables. 30 Gratifications of Digital Music Piracy Personal satisfaction • Accomplishment