Copyright © 2009 by Walter G

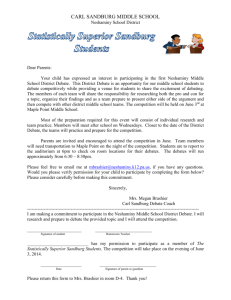

advertisement