verboten.doc

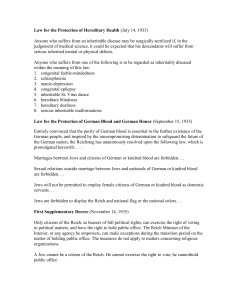

advertisement

I was a country once. I was Jordan in the mini United Nations. They passed out countries like baseball cards and we solved the “Palestinian Question” in just five months (in eighth grade). We tabled the problem at desks that made a hexagon when shoved together. Negotiations lasted up to our final deadline, when, EUREKA! We proposed a landfill (!) as a new home for the Palestinians. Yeah, wouldn't it be cool if we could take everybody's refuse and build a new island? We were considered thrifty (little did we know, Staten Island had already thought of it). We drafted a letter to Arafat and sent it off to whatever lucky middle school got to be the PLO. It's amazing what you can do with countries in your mind. 1 verboten Tanya Karini's parents broke it to me that I must be German, though I was suffering at that moment in hot Russian knickers and an oversize peasant blouse. My Russian grandparents had helped me dress for the fourth grade culture fair, and I milled around the gymnasium in itchy Russian clothing, like a wilting Cossak dancer. The Karinis suggested, we, the Sniders, were actually German Jews somewhere deep inside ourselves. I could be wearing a muslin dress. I daydreamed about this costume change against the pattering of Patrick Heinz’s Irish step dance, which he performed with pink cheeks the size and shape of two blush cakes. Snider is derived from the German word for “tailor,” Schneiderman, but the Germanic legacy and the art of sewing evade me. My sister, however, is a deft seamstress, and moved to Berlin last September. On the day she left, I escorted her to the Lufthansa terminal where we sat waiting in a wash of bright Lufthansa yellow, a color which suggested her travel might be something like Sesame Street with wings. There were no pictures at the terminal to illustrate what Germany itself would be like, though, and Steffi had never been there before. When the airport attendants scanned her through the metal detector, she whispered, "I can't believe I am allowed to go to Germany." 2 Before she left, many people said to my sister, "Berlin is not really like Germany. It's an international city, just like Paris," implying that real Germany might be something less pleasurable, something to avoid. I watched my sister walk away until she was the size of a small gumdrop. It occurred to me at the Lufthansa terminal, that my knowledge of Germany had not progressed significantly in the twenty-one years since my visit to Epcot, when I tried to visit little Germany-in-Orlando with my grandparents and my sister. In 1981, Epcot Germany emitted something cheerful, music by which to knock your knees. My sister and I faced the Bavarian pavilion and watched its visitors leave the compound with jumbo hot dogs and pretzels. Inside, I imagined the visitors flapped their arms to music made by yodeling ladies, German Swiss Misses, if their arms were not already filled with heavy steins of beer. Beer in Epcot, of course, might actually be sparkling cider or flat apple juice. We would never know the alcoholic proof for certain since my grandfather made it clear from his wheelchair that Epcot Germany was verboten. We pushed my grandfather's wheelchair past the compound while imagining those luckier children eating knockwurst, drinking kiddy-beer and grooving to techno beats. "It's PLAStic," I whined (emphasis on the silent 'the-world-is-so-unfair'), still believing I could make my grandparents sweet on Germany, just as I foolishly believed I could convince them that eighty degrees was too hot to wear thick, wool sweaters. 3 I was nine years old on this trip to Florida and all Jewish children my age had already been haunted with stories of Nazi Germany, the collective force that stole children and parents at night from their homes, stories so unbelievable, where bad things do come true—stories where children were put in ovens. My father's father had shared his hiding story, describing an architecture whose dimensions I retooled periodically. I first understood that he hid in a small toilet in Russia. I later deduced that he had actually lifted the toilet to descend into the secret compartment beneath the porcelain prop, where he hid until he could travel safely in a small boat to the United States. did grandpa hide in here? no, in here. The connection between the toilet-annex and Bavaria was real but unclear, and I presented this disconnect doggedly in front of Epcot Germany. My grandfather was recovering from a triple bypass while we scaled Space Mountain and still I believed I was 4 smarter because I knew this "Germany" wasn't Germany at all; it was an imagined community. I wanted to know how something plastic could really be good or evil, whether plastic was capable of good and evil, contained any moral character whatsoever. I would be going into Bavarian Germany with horned helmets and folk dances, a different place. But my grandfather did not want us to see Epcot Germany without remembering the Holocaust, distracted by a mound of sauerkraut and an Oompah band. Eventually, we accepted this. Most of my grandfather's family had escaped the concentration camps and this made him a specific kind of survivor, a survivor who escaped rather than witnessed. But maybe this made the general horror boundless for him as it did for many Jews then, and as it does for many Jews now who identify more strongly with the Holocaust than they might identify even with their own Jewishness. When my grandfather shook his head, he was saying to us at once: “you must understand" and "you can't understand" and so we've strapped ourselves to this task of knowing that we can never know Germany the way he knows it, though he has never traveled there himself. I tried to understand my Grandfather's Germany, picking up cultural clues from approved sources, then added information from accidental encounters, resulting in an eclectic composite made from Holocaust museums, cartoons, and Sunday School teachers: THINGS I KNOW ABOUT GERMANY Haribo candy Kinder chocolate 5 Beer steins Octoberfest Nazis Concentration Camps Mercedes-Benz Volkswagen Neitzche Berlin Wall Camp counselor with bad body odor Cartoon about girl trapped on other side of wall from family Kraftwerk Neu Knowckwurst Bratwurst Leiderhosen "gezundheit" Augustus Gloop, if he is not Austrian At Temple Beth El, we began as young architects of civilization, building small biblical models for the annual diorama competition. We built entire families into boxes we converted into small harvest huts—one room at a time, one shoebox per room. The rules were simple: build a Sukkah, a small hut like those built by Jewish nomads in the desert during harvest season. The eaves lay spaced apart on the "top" (side) of the "house" (box). We cut into brand names like Buster Brown and Zips for the strips of sky to come through, down to the little people, rendering words on the box into semiabstraction, only half-obliterating our present. No matter how biblical the scene, you often ended up stuffing plastic Fischer-Price people into place if you didn't feel like making them, though these figures were conspicuously coifed and blonde for desert Jews. It was okay if you stuck mini Coke cans on the family's table, which was made from a sewing thread's spool. Biblical desert according to suburban Detroit. 6 My confidence in replicating world history out of clay and cardboard and general vapors (movies, television, books, etc) waned when I encountered Mrs. Stern, a leathery lady with a smoker's croak who made it her mission to teach all the seventh graders at Temple about the Holocaust. Mrs. Stern told us many unsettling things. "Kids, don't ever forget the number six million, "she said. "That is the number of people who died in the Holocaust. Many of them were children. Six million…" She said the number over and over. [sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion 7 sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillionsixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion sixmillion] "...just like you," she said. And just in case Mrs. Stern had not made her point clear enough, she added: "That's like someone knocking on your door tomorrow." Nazis. And we would be unprepared. 8 Mrs. Stern was not a good storyteller—she always skipped to the end and the end was always tragic, sordid, or frightening, her eyes popping wide open for emphasis. She was the woman who told us the story about the shoe flying across the room that hit the boy in the temple and he died and the boy who fell through the unfrozen ice and died, and the girl who sat on the open scissors, and the pencil that stuck in the (same?) boy's eye and he didn't die but he no longer saw. Her curriculum was ALARMIST, and went well with my day school’s lessons in which most recently, a firefighter had concluded his fire safety presentation by encouraging all students to pack a small bag or suitcase with "disaster" necessities — a blanket, etc—to keep under our beds. These notions of imminent doom became an extracurricular preoccupation as well. I played the "Hitler's coming" game to go to sleep each night. In this game, I imagined I was floating on a glacier-like body—my bed—with over forty stuffed animals. Only those children and animals who looked asleep would live. Not only did you have to pantomime sleep but you had to have the subtle sophistication to know this involved some mumbling and tossing. Only a person faking sleep is still. A real sleeping person is never fearful of looking awake. I'd play until I fooled myself into a real sleep, the first cycles of REM. Mrs. Stern told us the story of the Benz family. The Benz story was simple: the Benz family (of Mercedes-Benz family fame) provided the gas for the gas chambers in the Holocaust. 9 "Don't ever get into a Mercedes-Benz," she growled. The news was bad. My mother showed up that day to take me home in her old maroon Mercedes wagon. When I refused to get into the car, she told me to suit myself, with full confidence that my transportation options were slim in the suburbs at age twelve. My boycott was selective and brief but I always remembered the blood was on our hands when we rode in the wagon. It surprised me then, two years later, when I visited Israel and the streets were filled with Mercedes-Benz cars and trucks. When I inquired about this conspicuous presence, I was told that Mercedes-Benz had cut a deal with the state of Israel, and offered a shipment of cars as reparations. How did this work? A] Here are some cars? B] Here are some coupons for cars? C] Let's make a deal? My grandparents only drove American cars. In Metropolitan Detroit, we regularly visited the Henry Ford Museum as a weekend excursion, which paid tribute to the invention of the automobile and was also part of the larger living-history center of Greenfield Village. Here, you can visit the chair where Abraham Lincoln was shot, extracted from the Springfield, Illinois theater. My grandparents held onto their 10 prejudices selectively. Never mind, by the way, that Henry Ford was a reputed antiSemite. My grandparents sought refuge in fake comforts like non-Germany, or nonGermanness even when those alternatives presented problematic Americanness. It was more important that the Ford cars delivered them from the German market even though the American auto industry wasn't doing anything good for the Jewish man or woman. Henry Ford published two documents, at least one of which he distributed throughout his factory, the infamous “Protocols of Elder Zion,” and “The International Jew:The World's Foremost Problem (Recently, Ford Motors sponsored the airing of Schindler's List on NBC)". Just up the road, Father Coughlin was preaching the same anti-Semitic racket and my great-aunt Mimmy spit out her American car's window every time she passed Coughlin's church on Woodward Avenue, even after he died in 1979. When I remember Mrs. Stern, I begin to think I sometimes collapsed my idea of Germany with its histrionic messenger. I might have confused her harsh delivery with Germany itself. If she told us of storybook Germany, she told us storybook Israel, too, imploring that we join the Zionist movement if we were worth our kosher salt, though most of us were counting down the days until our bar or bat mitzvahs when we'd quit Sunday School. Here, I experienced some imaginary Jewishness in an imagined community. I knew the entire Hebrew school carpool hated me and it might have hinged on something small and secular like not wearing a large banana clip in my hair. That wasn’t very pious at all — where was their rachmones? I figured I had plenty of non- 11 Jewish friends waiting for me who had no plans to live in trailers in the occupied territories. I never learned much about Germany beyond my lessons in Sunday School, but took it upon myself as my responsibility to be self-righteous, as a general attitude, about something, anything, since righteousness skips generations, I believe. It was my turn to be indignant about the Holocaust. Now, I am dissatisfied with my Germany made from Mrs. Stern and made of the knockwurst, leiderhosen, the Alps my undisciplined mind borrows from the Swiss, about my ignorance, which is cluttered with an excess of images. I confess — I sometimes forget that I did travel once to Germany, several years before my sister moved there. I visited Munich briefly when I left college. I stayed with nuns in a tall boarding house located in the red-light district, a short walk from the train station. In my narrow bed, I read Sophie's Choice straight through in two days while coughing up bright green sputum and slugging down Dr Trink's multivitamin juice. No one spoke English and I learned only the German word for "juice" which I have now forgotten. On the third day, I emerged from the boarding house and took a short bus ride to Dachau. I visited the concentration camp through the haze of a heavy rain, Sophie's Choice, and mucus, like sleepwalking. Mostly, while there, I thought about Steven Spielberg's insistence that we preserve the crumbling concentration camps as evidence, 12 while those opposed argue we should let the camps fall. Why spend money on Nazi artistry? Would this, people have argued, make it Epcot Dachau? Back at Greenfield Village, conservators are scratching their heads over the very same pickle: How to preserve the blood on Lincoln's chair now that it's fading. How to keep it real. In my travel journal, I made assorted notes on Germany: On Dachau, I wrote: How could one say s/he lived in the town of Dachau? What a shameful history. The Holocaust leaves you with an impossible kind of mourning to do— self-indulgent, melodramatic or merely inadequate. Dachau was almost a park. In more assorted, paranoid moments, I wrote: How the hell did I end up in Germany?! I'm scared here. It is hard to deduce much of anything. The tourist office is closed. In fact, I don't even know the name of the station I'm in. Last night a Christina Crosby doppelganger [a professor of mine—and score three points for German word] sat beside me and scarfed down what appeared to be softened deep-fried Trix cereal, which I imagine has some name like "schnitzel." It's apparently quite acceptable to stare here. I guess sausage is very "in" here. I thought the cashier was going to beat me over the head with her ladle. Why do the nuns hate me? And why hasn't anyone said "gezundheit" when I sneeze? And why was the man next to me on the train carrying a five-foot sword and a cream pie, in black leiderhosen, accompanied by another man in black leiderhosen 13 and a woman in green velvet with pinched cleavage? Why weren't the two men in black leiderhosen speaking to one another? Abruptly, in a most revealing nonsequitur, I state my desire to flee: They are now trying to find the Yeti in China/Tibet. Maybe I can help (?). I barely made it back from the Dachau excursion before the ten o'clock curfew when the nuns lock the doors to the boarding house and leave all the tardy boarders to the wolves on the strasse. Inside, all the girls were eating cake in their nightgowns. None of these events managed to lift the shroud of mystery surrounding Germany; its forbidden character was merely scrambled by the surreal details of the experience. In fact, Germany's reality didn't stick. Ultimately, though, I experienced these things German with a sense of entitlement; I felt entitled to feel squeamish. Cleveland’s newspaper, The Plain Dealer, recently reported that Germany's Jewish population now exceeds 100,000 for the first time in post-Hitler Germany. Germany's Jewish community before Hitler's rise numbered over 500,000. The new movement of Jews back into Germany constitutes the most accelerated migration of Jews in the world. Last year, the Jewish Museum in Berlin opened after many false starts and architectural snafus. In 2004, Berlin will install a new Holocaust memorial near Brandenburg Gate, designed to suggest a large cemetery, and will be built on top of an underground education center. The question remains for Germans and Jews (and German 14 Jews): What does Germany owe? Is debt relevant to the youngest generation of Jews and non-Jews in Germany? Thousands of Jews more closely tied to the Holocaust than I, are crossing the borders into Germany. In recent years, Daimler-Benz published a document chronicling its cooperation with the Nazi regime entitled "Forced Labor at Daimler-Benz" and attempts to contact people involved in the forced labor for reconciliation. Still, many Jews around the world and other veterans of World War II boycott German products, including Bayer aspirin, Krupps and Braun products, and Mercedes-Benz cars. My grandparents once comforted themselves by buying American cars and now even these conceits are impossible. Those who vowed to buy American are betrayed by the car companies themselves, corporations like Chrysler who merged with Daimler Benz over one year ago, one nation divisible after all, grafted onto another. The Mercedes-Benz homepage advertises its own global vision; "In a perfect world, everyone would drive a Mercedes." My more personal question is why didn't Munich stick? Maybe it's my Americanness—my interest in models, dioramas, and Epcot, and my interest in the fake. What use is the myth? Especially when it contains two sensibilities so starkly opposed, such as warm, hearty stews and human cruelty, cuckoo clocks and black shiny boots? I 15 did briefly think I might use more sociological methods to gather specific information about Germany, and sent a short questionnaire to my sister after her first week in Berlin. 16 QUESTIONAIRE FOR FRAU SISTER STEPHANIE SNIDER (use back if necessary) 1. What does Germany look like? 2. What do you see in front of you? 3. Do Germans wear brown muslin? Can you be sure? 4. What are you eating? 5. Are you scared? 6. Do you think about the Holocaust more in Germany than you do in the United States? 7. Do people stare? 8. What do you think Epcot Germany looks like? 9. What does it sound like? 10. Would you marry a Jewish German man? 11. Would you marry a non-Jewish German man? 12. Is German posture different? 13. How is your posture? 17 ANSWERS 1. It is very beautiful, wooded, with a huge lake called the Wannsee. This area looks like a German Bloomfield Hills — an incredible mixture of old and new. I play a game where I count all the cranes I can see from the S-Bahn (elevated train), …lots of new buildings for the former empty spaces…usually in the former east. 2. I can see the grounds of the American Academy and the lake, the Wannsee. There are also many sailboats docked nearby. 3. No brown muslin yet, but I imagine they do in Heidelberg or maybe in Bremen 4. Weinerschnitzel, bratwurst, currywurst, sauerkraut, and of course mineralwasser. 5. Not yet 6. Yes, without question. You sometimes find yourself asking yourself, somewhat casually, could I hide there? 7. Yes. I wonder if it is because I look Jewish? I am not sure but they definitely do. 8. It probably looks like old German tudor-esque with brick and plaster, very much like the fairy-tales! 9. There is a man at the Kunstlerhaus Benthanien with the last name of "Liebkuche." I like this name because it literally means "love cake." One hears "Ah so," which I think means "Oh, yes" and also "Tchuss!" which means see you later. Also "weider" which means again. 10. Yes, maybe 11. Yes, maybe 18 12. Not that I can tell 13. I think it's better! 19 EPILOGUE Each phone call from my sister punctured my German fantasy life and I necessarily scaled back the Germanworld which I had begun to think of as almost smurflike or schtrumpf-like—each busy German doing his or her part in a buzzing mushroom town with simple personalities (smiley, lazy, selfish, wise). Steffi called me in Brooklyn with terribly boring (by comparison) regional news—the S-Bahn, the art scene, the old man she likes to visit on Fridays—and then she said her new neighborhood, just outside of Berlin, looked like the suburb where we grew up. Just when I thought it might be time for me to catch up with the Germany of today, I received a panicked call from Steffi on Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year. Earlier that day, an older Jewish man and woman had visited the Academy where my sister now lived. The woman told my sister that her family had lived in the large house until they were forced out by Hitler, and she then pointed to the area underneath the building, which she identified as one of Hitler’s favorite bunkers. My sister could not believe she was now living on top of an SS bunker, and walked around chilled for several weeks while the other residents got by with a small shudder. She began to build small models of bunkers out of wood and cardboard, impossible architectural structures with no way out, and painted them gray. 20 By November, I could hear a new inflection in my sister’s voice and eventually, I could hear her sighing or stumbling in German instead of English. I heard a lot of “Ah, zo”s and “er”s instead of “um”s. Her facility with the language came in handy when she broke her nose in a shopping mall and was forced to describe to the doctor—in German —what her nose once looked like. And my sister couldn’t help but make the most evident observation—she was a Jewish woman with a nose job in Germany. I told Steffi it really was like the suburb where we grew up, where the girls there wore Band-Aids across the bridge of their noses, too, when they fixed them (which they frequently did). Her nose was reset to its former shape though my sister still complains it’s now larger instead of smaller, and she walked with her hands near her face for many weeks after the accident, believing our faces to be exceedingly vulnerable. It took me eight months and several small gifts of courtship from my sister to make a trip to Berlin and I couldn’t help but check the toilets once I got there, lifting up the seats and tugging at their immovable porcelain bases. When I heard the German language, I remembered my previous visit; sounds like doors shutting in faces, interrupted and harsh with so many consonants pushed together. But it sounded like my grandparents, too, who spoke Yiddish when they did not want us, the kinder, to understand what they were saying. My touring itinerary was based on the must-see sites of Berlin plus freestyle ambling, limited by gray weather and mutual depression. We mixed up a little 21 Checkpoint Charlie with several museums and an American movie. To my sister’s chagrin and my delight, my visit coincided with Berlin’s five-day Bavaria festival. The food-servers under decorative tents were actually impersonating themselves! It was like the German Culture Fair for Germans. With costumes made of thick felt materials. This only helped to confuse the regional distinctions upon which Steffi insisted. Eventually, she gave in and took me to the beergarden/petting zoo combination after several museum trips. I did feel some personal triumph that I could match vague homegrown fantasies with these real sightings, like pulling a second matching card in a game of Memory. When my sister left for Germany last year, she planned to visit Berlin for 8 months on a fellowship. Now, 17 months later, I guess she lives there. After September 11, she was shaky and determined that we not drink the water here in the United States. She followed up this instruction with a panicked phone call proposing that my family immediately relocate to Berlin, where we would temporarily live with her in her apartment. Steffi reconceived of Germany as a safe harbor, and her home as a possible family bunker. Weeks later, when terrorists were arrested in Germany and the German government proposed iris scans at airport checkpoints, Steffi threatened to leave Germany. “If the iris scans are approved, I am leaving,” she said. I reminded her that the Amsterdam Airport already used iris scans to ID passengers. 22 “But it’s different in Germany.” Steffi was describing a resonance with which she experiences Germany, a loyalty to a collective bodily memory of final selection. There wasn’t so much obvious Germanness in Berlin, or maybe there was and I couldn’t recognize it because I was looking for something different. I wondered if people were staring at me in Berlin, and in my preoccupation, I would often lock eyes with a poor commuter who I’d been challenging to stare at me for extended periods of time. When someone did stare, I felt triumphant until I realized that it most often turned out to be someone staring back. I made myself conspicuous preemptively. I feared the reality of Germany would seep like a large inkblot over my tangled myth but somehow, the two realms of reality and fantasy don’t even seem interested in one another. Even my most progressive Jewish friends feel half-comfortable hating Germany in an uncharacteristically inherited rather than political stance, forcing ourselves into caricatures of Jews making caricatures of Germans, cartoon images airy and expandable like comics imprinted on silly putty. And this caricatured Jew feels unwilling to give Germany the understanding with which s/he gives his/her own country, the United States, which is, itself, an exemplary model of unspeakable crime and virtue. Most of the people we believe we are honoring with emotional sanctions are dead or dying and we, in truth, actually like to read the great thinkers of Germany and celebrate the great artists of Germany, secretly, away from our Grandparents. Max Weber himself, a German man, 23 was the one to first articulate the concept of charisma, which theoretically explained the very mechanism by which someone like Hitler came to power. I don’t think myths die when they’re proven wrong but instead when they become boring. My imagination eventually feels as though it’s reached its limit on a topic and there is nothing left to riff on, even the riff has been riffed. My grandfather assumed the manic cuckoos and Oompahs would convert me to a friend of Germany. Epcot Germany might actually have been menacing and garish in its optimism. Certainly, Epcot’s Germany is dated. It doesn’t speak of the New Germany, the new Berlin. Berlin may be part of the Brave New World in all senses— a pioneering city with a brand new post-wall life, but a city with spies in the midst, even if it is history and our paranoid fantasies that watch over us. 24