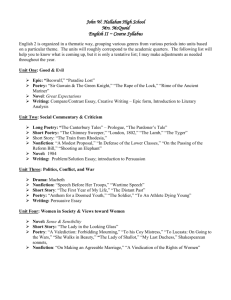

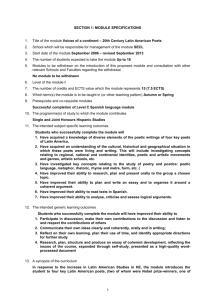

American Poetry Since 1945: The Anti

advertisement