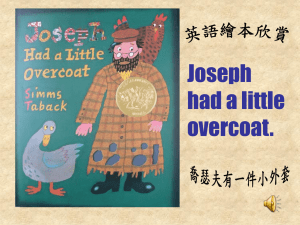

The Joseph Narrative as a Model for Future Generations

advertisement

Bar-Ilan University Parashat VaYigash 5773/December 22, 2012 Parashat Hashavua Study Center Lectures on the weekly Torah reading by the faculty of Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel. A project of the Faculty of Jewish Studies, Paul and Helene Shulman Basic Jewish Studies Center, and the Office of the Campus Rabbi. Published on the Internet under the sponsorship of Bar-Ilan University's International Center for Jewish Identity. Prepared for Internet Publication by the Computer Center Staff at Bar-Ilan University. 947 By Gavriel Haim Cohen* The Joseph Narrative as a Model for Future Generations It has been said that the idea, "derekh eretz—common courtesy, respect, proper behavior— comes before Torah," provides an answer to Rashi's famous question of why the Torah begins with Genesis and not with the text, "This month shall mark for you" (Ex. 12:2), which is the first commandment given the Israelites. Genesis provides a concrete illustration of the common courtesy of our ancestors in all its manifestations and it therefore serves as a suitable introduction to choosing Israel and giving the Torah. The lives of our patriarchs and matriarchs are edifying for all generations. The Joseph narrative is undoubtedly important in learning how one ought to behave. The dramatic intrigues in Jacob's household provide a unique and fascinating lesson in how we should cope with our own weaknesses and correct them.1 * Dr. Cohen is a lecturer in the Bible Department at Bar Ilan University and at the Lander Institute. 1 Many commentators and Bible scholars have dealt with mending one's ways as reflected in the Joseph narrative. See Uriel Simon, "Yosef ve-Ehav—Sippur shel Hishtanut," Bakesh Shalom ve- Rodfehu, Jerusalem 2002, pp. 60-87. In this article we try to show the process of mending ways and rehabilitation in each one of the characters in the Joseph narrative. 1 As the narrative opens in Parashat Va-Yeshev, we see all the characters in Joseph's life in their moments of weakness. All of them, each in his own setting, contribute to the destruction of Jacob's family, the House of Israel. Jacob openly favors Joseph, Rachel's firstborn, over his brothers, in an offensive way: "Now Israel loved Joseph best of all his sons, for he was the child of his old age; and he had made him an ornamented tunic" (Gen. 37:3). His special treatment of Joseph is the basis of all the contention and hostility in the Joseph narrative.2 Joseph himself acts high and mighty. He brings bad reports of his brothers to his father and at a certain point flaunts his status (perhaps also in response to his father's words) and reveals his dreams which clearly hint at his ruling over his brothers. The brothers are quick to react with jealousy and hatred. When Joseph visits his brothers in Dothan they scheme against him, plotting to kill him. Only Reuben's intervention prevents the murder, but in the end Joseph is sold down to Egypt as a slave. We have here a story of a dysfunctional family whose members destroy all that is good. Then, towards the end of Genesis, after a complicated, tension-filled process, each of the characters in the Joseph narrative repents fully and acts properly when presented similar situations to those in which they had previously failed.3 The brothers come to realize that the way they treated Joseph had been a crime. Even in their first encounter with Joseph in Egypt they view their troubles as punishment for how they had treated Joseph: "They said to one another, 'Alas, we are being punished on account of our brother, because we looked on at his anguish, yet paid no heed as he pleaded with us. That is why this distress has come upon us" (Gen. 42:21). That they repented fully is evident later on, when they do all that is in their power to save Benjamin. Bear in mind that history was repeating itself here. The brothers again found 2 From the context and a close look at the language used in Scripture it is evident that the issue here is not loving emotionally, rather choosing Joseph as Jacob's heir. Israel (the national name) loved and singled out Joseph from among all his sons because he was the child of his old age, the child held in mind in one's old age when determining who will be one's heir (see Gen. 24:1; 27:1). Jacob made Joseph an ornamented tunic, the symbol of sovereignty and kingship (II Sam. 13:18-19; Isa. 22:21). Joseph's dreams the father "kept to himself," for they appeared a prophetic expression of the realization of Jacob's plans. 3 Maimonides defines total repentance: "When a person is presented with a situation previously experienced and has the possibility of erring again but does not, because of repentance and not out of fear or lack of strength" (Hilkhot Teshuvah 2.1). 2 themselves confronting their father's especial love for a son of Rachel. But this time they do not abandon him to his fate, even though they could have done so since he had apparently stolen the royal goblet. At first, all the brothers are willing to become slaves along with Benjamin: "Here we are, then, slaves of my lord, the rest of us as much as he in whose possession that goblet was found" (Gen. 44:16). At the next stage, in this week's reading, Judah, as spokesman and uncrowned leader of the brothers, in a dramatic oration offers himself as a slave in place of Benjamin: "Therefore, please let your servant remain as a slave to my lord instead of the boy, and let the boy go back with his brothers" (Gen. 44:33). Under no circumstances are the brothers willing to abandon Benjamin, Rachel's son, and cause their father everlasting sorrow. Thus they show their desire to make amends for having sold Joseph. Joseph shows in a variety of ways that he does not hold a grudge against his brothers for having sold him, rather he receives them as his guests in Egypt with a generous hand. Joseph is now willing, after the brothers have repented and shown their devotion to their father, to disclose his identity and renew his ties with his father.4 Joseph consoles his brothers, saying, "So, it was not you who sent me here, but G-d" (Gen. 45:8, and cf. 50:20). The brothers' fears, after the death of their father, that perhaps Joseph still bears them a grudge, and their appeal to him in the name of the father to forgive them and not punish them evoke a sorrowful response from Joseph: "And Joseph was in tears as they spoke to him" (Gen. 50:17). Especially impressive is the way Jacob changed for the better: what would have been more natural for Jacob, head of the family, to choose Joseph as his heir at the end of his life? Throughout his years in Egypt, Joseph showed leadership ability beyond the slightest doubt. Joseph was also gifted with a fine character and high level of morality. Unlike Reuben and Judah, who had moral failings in their relationships with women—witness Reuben's affair with Bilhah and Judah's with Tamar—Joseph heroically withstood the attempts of Potiphar's wife to seduce him. 4 Joseph, who had shown a shortcoming in bringing bad reports of his brothers to his father, refrained from contacting his father until after his brothers had fully repented. He did so in order to preclude needing to speak ill of his brothers again and thus ruin the family unity. Thus Joseph also fully mended the ways of his youth. Cf. Nehama Leibowitz, Iyunim Besefer Bereishit, Jerusalem 1967, pp. pp. 325-328. 3 But lo, we are presented with a surprise: Jacob chooses Judah, Leah's fourth son, to be the leader of the House of Jacob, that is, of the Jewish people in future generations.5 Jacob understands that he cannot impose his will on his sons. He therefore chooses a course that shows the budding signs of democracy—selecting a son who is acceptable to his brothers. Jacob awards the double portion of inheritance due to the firstborn to Joseph—"Ephraim and Manasseh shall be mine no less than Reuben and Shimon" (Gen. 48:5)—but he does not confer on him the role of leader. That role he gives in no uncertain terms to Judah:6 "You, O Judah, your brothers shall praise…The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler's staff from between his feet; so that tribute shall come to him, and the homage of peoples be his" (Gen. 49:8-10). The midrash expands on Judah being chosen and the significance of this choice for future generations (Genesis Rabbah, 98.6): Your brothers praise you, your mother praises you, and I myself praise you. Rabbi Simeon ben Yochai said: All your brothers shall be called by your name, for a person does not say, I am a Reubenite or I am a Simeonite, but I am a Yehudi (Jew). Indeed, Jacob realized his mistake and mended his ways. The Joseph narrative provides a model for future generations how not to give in to one's darker desires that bread tension in family life and destroy Jewish homes. They teach us that we must all work hard to improve ourselves and to act responsibly and out of love for the Jewish people. Translated by Rachel Rowen 5 Although in Joseph's absence Judah proves himself a worthy leader, nevertheless Joseph's ability to rule is evident in his own right. See my article, "Manhigut be-Imut be-Sippurei Yosef," Hagut ba-Mikra IV, Tel Aviv 1984, pp. 129-149. 6 Reuben, the firstborn, ought to have been "exceeding in rank and exceeding in honor" (Gen. 49:3), but because he violated his father's concubine he was not found deserving of either, and these blessing were divided between Joseph, Rachel's firstborn, and Judah (cf. I Chron. 5:1-2). 4

![Title of the Presentation Line 1 [36pt Calibri bold blue] Title of the](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005409852_1-2c69abc1cad256ea71f53622460b4508-300x300.png)

![[Enter name and address of recipient]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006894526_1-40cade4c2feeab730a294e789abd2107-300x300.png)