theingi.doc

advertisement

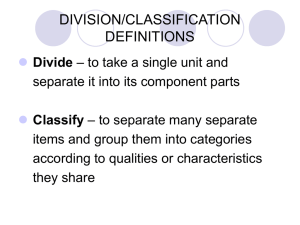

WHAT MAKES ONLINE SHOPPERS DIFFERENT FROM NON-ONLINE SHOPPERS IN THAILAND? Theingi*, Department of Marketing, Martin de Tours School of Management and Economics, Assumption University, Thailand email: theingi@au.edu Cho Mon Aung Department of Marketing, Martin de Tours School of Management and Economics, Assumption University, Thailand email: chomonaung@hotmail.com * Corresponding author (Author has only one name). Abstract This study conducts 3 focus groups to understand the online shopping process of Thai consumers and presents descriptive characteristics of online and non-online shoppers in Thailand. This study also examines the factors that differentiate between online (N= 581) and non-online shoppers (N= 485) in Thailand. The findings indicate that online shoppers are significantly different from non-online shoppers in many aspects. Online shoppers in Thailand are more likely to engage in both traditional and online word of mouth communication, have lower perceived risks and higher level of positive attitude toward online shopping, are more willing to have personal interaction with online vendors, have lower perceived price and are more attractive to online promotion than non-online shoppers. Keywords: online shopping, personal interaction, word of mouth communication, Thailand. 1. Introduction Internet retailing or e-retailing is a growing phenomenon around the world due to the ever increasing usage of the internet. Between 2005 and 2009, the global internet population increased from 1 billion to 1.6 billion people (IMAP, 2010). According to the Nielson global online survey, about 875 million people (one-eighth of the world’s population) have shopped online and these people accounted for 85% of the world’s online population (Nielson, 2008). However, internet penetration in Asia (23.5%) is lower than the world average (30.2%) (Internet World Stats, 2011). In a similar trend, the number of internet users in Thailand is relatively low compared to other Asian countries like China, Malaysia, South Korean, Japan, Philippines even though trend had been growing dramatically to 18.3 million users (27.3% of Thai population) in June, 2009, with a 13.7% growth from 2008 (NECTEC, 2011; Internet World Stats, 2011). According to the Nielsen (Thailand) report in 2008, 61% of Thai internet users had used the internet to make a purchase with the growth of 27% compared to the past two years. Nearly 73% of e-commerce transactions in Thailand were targeted at final consumers and valued at 63.4 billion baht in 2008 (Pornwasin, 2008). Moreover, during the past four years, the number of online shoppers in Thailand had increased 30-40% due to the growing number of online retailers and relatively low investment required in starting online businesses (Chinmaneevong, 2009). For example, http://shopping.sanook.com/ has 27 categories and 186 sub-categories of products and services, with around 200,000 new items added per month. It is the most popular website in Thailand drawing 1 million visitors daily selling variety of products in association with eBay. Despite the fast growing e-retailing market, marketers have a limited understanding of internetrelated consumer behavior (Stewart, Wettstein and Bristow, 2004) especially in developing countries like Thailand. In Thailand, the main reasons against online purchase were risk-related factors such as lack of trust toward merchandisers, lack of physical touch regarding products, and unwillingness to reveal credit card numbers, and Thai consumers’ perception towards online purchase as a high risk process (Laosethakul and Boulton, 2007). Due to high uncertainty avoidance and collectivistic nature (Pornpitakpon, 2000), Thai people tend to seek information and the opinions of others in an effort to save search time about the product and to lessen the risk in purchasing online. However, most studies to date have mainly investigated the word of mouth communication as post purchase behavior of consumers (Brown, Barry, Dacin, and Gunst, 2005) and ignored the important role of both traditional and online word of mouth communication in determining online shopping behavior. Moreover, the importance of personal interaction between online shoppers and sellers is largely ignored in online shopping literature. Thus, the main purposes of this study are to understand the online shopping process of Thai consumers and to explore the differences between online and non-online shoppers such as in terms of word of mouth communication and personal interaction between sellers and buyers. In this study, an online shopper is defined as an internet user who bought or ordered goods on the internet by making payment in the form of bank transfer or credit card or any other online payment. 2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development Many previous studies on online purchase behavior have focused on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in explaining the internet adoption process and purchase behavior. According to TPB, attitude toward behavior, subjective norms (perceived social pressure) and perceived behavioral control (people’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest) influence intention which in turn determines purchase behavior (Ajzen, 1991). In addition, Mitchell (1999) argued that the perceived risk of using the internet was paid attention by many marketing practitioners and researchers since it was powerful to explain consumer behavior. Due to the high uncertainty avoidance nature of most Thai people (Pornpitakpon, 2000), it is worthwhile to investigate the factors reducing perceived risk in online purchase. Based on these theories, this study examines how attitude, perception and perceived risks differentiate between online and non-online shoppers. 2.1 Perceived Risks Sheth and Venkateson (1968), based on the risk-taking theory, reported that during the purchase process, most consumers had some level of perceived risk. Perceived risk was defined as a perception of consumers on uncertainty and negative consequences in purchasing a good or service (Dowling and Staelin, 1994). Lwin and Williams (2006) indicated that shopping online (non-store retailing) was riskier than shopping at traditional stores, due to the e-security concern (Helander & Khalid, 2000). Moreover, Bramall et al., (2004) also argued that reduced perceived risk associated with buying from a particular online retailer tends to increase consumer’s willingness to purchase from that online retailer. Hence, it is imperative that reduction of perceived risk could lead to consumers’ willingness to shop online. It is hypothesized that H1: Online shoppers tend to have lower level of perceived risk than non-online shoppers. 2.2 Word of Mouth Communication Several previous researches discussed how consumers’ perceived risk can be reduced in different ways. Based on the findings of a number of scholars such as Dowling and Staelin (1994) and Chauduri (1997), consumers searched for information to avoid or reduce the perceived risk. Moreover, according to Chaudhuri (2000) and Larson, Engelland and Taylor (2004), consumers searched more for information when they perceived that there was a high risk when purchasing products. Consumers tend to have a low level of confidence while purchasing online due to lack of experience with products in terms of tastes, sounds, scents, tactile impressions, and visual images (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982). To overcome this limitation, traditional as well as online WOM from other people provided indirect experience of products to the consumers (Park, Lee and Han, 2007) and allowed consumers to save search time about the product (Henning-Thurau and Walsh, 2003). According to the Neilson’s study in 2007, 51% of Thai respondents consider web-based opinions as sources of trustworthy information and 81% of them trust what they hear from other consumers (Neilson, 2007).The above behavior is consistent with the Theory of Risk Taking (Taylor, 1974) which discussed that the consumers tended to reduce the uncertainty of outcome by seeking word of mouth information. Westbrook (1987) defined word of mouth communication as an informal communication between two or more customers about the products or the firms. There are two types of word of mouth communication (WOM): traditional and online. Sun, Youn, Wu and Kuntaraporn (2006) mentioned in their study that traditional WOM consisted of spoken words exchanged with a friend or relative in a face to face situation while online WOM usually involved personal experiences and opinions transmitted through the written word. The online WOM had widened the circle of sources and was found in the form of consumer chats, guest books, discussion forums and boycott sites. Moreover, with the growing popularity of social networks such as hi5 and Facebook, these networks could become an effective source to reach a larger number of consumers (Maneerunsee, 2009) and to conduct online WOM. Previous literature showed the effects of positive WOM for online retailers as being the most effective form to advertise (Enos, 2001). Park, Lee and Han (2007) also found that at Amazon.com, online word of mouth communication in terms of online consumer reviews has a positive effect on consumer purchase intention. Hence, it is likely that online shoppers seek more word of mouth information than non-online shoppers. Therefore, it is hypothesized that H2: Online shoppers tend to engage more in word of mouth communication than nononline shoppers. 2.3 Attitude towards online shopping Ryan (1982) found a strong impact of consumers’ attitude on consumers’ purchase intention. For example, a positive attitude toward e-commerce (Helander and Khalid, 2000), a positive attitude toward internet shopping (Shim et al., 2001), and attitude toward online stores (Kim and Park, 2005) have significant influence on online purchase intention. Kim, Kim, and Lennon (2009) also found consistent results that there was a positive relationship between the consumer’s purchase intention and their attitude toward a website. Moreover, Shim and Watchravesringkan (2003) also indicated a positive relationship between consumers’ attitude toward online shopping and online purchase intention for apparel. Hence, it is hypothesized that H3: Online shoppers tend to have a more favorable attitude towards online shopping than non-online shoppers. 2.4 Marketing related factors Consumers generally like to feel and touch the products, try them or test them out and compare the prices before they purchase the item (Monsuwe’ et al., 2004). For example, consumers consider purchasing standardized, staple or familiar goods online more than personal-care products since those products do not require pre-trial or physical contact (Monsuwe’ et al., 2004). According to a Nielson Global Consumer Report (2010), 46% of global consumers surveyed in 2009 purchased books in the last three months. Similarly, Balabanis and Vassileiou (1999) reported that one of the reasons for consumers not purchasing online was inability to touch the product. Bramall et al., (2004) also argued that expensive products and unfamiliarity with brand name enhance the perceived risk of consumers in making online purchase. Thus, products such as DVDs/games were the most popular purchase items among Thai internet consumers followed by books, computer hardware and air tickets (Nielson, 2008) because physical feel and touch were not that important for buying these products and they were less complicated in nature. According to Lim and Dubinsky (2004), prices and product comparisons could be done at the same time and reduced the search costs while purchasing online. Moreover, online retailers could offer promotional tools such as lotteries, online games, appetizers, special offers, and several links to other websites (Spiller and Lohse, 1998). These types of offers could lower their perceived risk of shopping online and enhance online shopping. Thus, if the product’s availability online had competitive price and promotion, it was likely to offset the risk of online transactions in consumer markets (Laosethakul and Boulton, 2007) and could lead to online shopping behavior. Hence, it is hypothesized that H4: Online shoppers tend to perceive lower level of product complexity, lower price and attractive online promotion than non-online shoppers. 2.5 Personal interaction with sales person The interaction between the store salesperson and consumers is one of the influencing factors on consumer purchase behavior in retailing. According to Reynolds and Arnold (2000), there were some consumers seeking to get assistance from the salesperson for reasons of social interaction and personal enjoyment. Moreover, consumer’s perceived risk was reduced by the assistance of the store salesperson and advice (Conchar, Zinkhan, Peters and Olavarrieta , 2004). In addition, Thai people perceived that online shopping was impersonal and lacked the human-touch activities (Laosethakul and Boulton, 2007). However, there is a lack of studies about the role of personal interaction with online retailers/sellers in online shopping. Sheth and Parvatiyar (1995) reported that the seller’s interactions with the buyer such as providing information and service during the purchase process could create buyer’s confidence in shopping in consumer markets. Thus, it is logical to assume that online shoppers are more likely to have personal interaction with online retailers/sellers, and non-online shoppers are more comfortable buying at the traditional retail stores. Hence, it is hypothesized that H5a: Online shoppers are more willing to have personal interaction with salesperson at online retail stores than non-online shoppers. H5b: Non-Online shoppers are more willing to have personal interaction with salesperson at traditional retail stores than online shoppers. 3. Results of Focus Groups This study employs three focus groups to have better understanding of Thai online shoppers; one focus group for university students and two focus groups consisted of working people of ages ranging from 18 – 35 years. Each group consisted of 6 participants and the duration of each focus group was approximately one and a half hours. According to the focus group results from 18 persons in total, the prominent reason for buying online is product uniqueness followed by product quality and variety, and lower prices. In addition, 50 percent (9 persons) of the participants mainly used the internet to search for the products of their interest and related information. The products that the participants were mainly interested in and purchased were digital cameras and spare parts, PDAs and mobile phones, fashion clothes and shoes, and MP3 players. Moreover, they intended to purchase some old products which are difficult to find in the market, such as limited or special edition products, and new fashionable products which were not yet available in Thailand. 3.1 Online shopping process When discussing online shopping process, the findings from all participants are consistent. As an initial step, like any other online shoppers in most countries, they searched for necessary information about a particular product such as product information and price from the various sources of websites. Most of the participants read the comments and reviews from the web boards and chat rooms, and also checked the ratings or votes by other buyers to reduce the risks. After price comparisons were made, participants called the sellers to check the seller’s credibility when browsing Thai websites, and to ensure the merchandise delivery, payment methods and security were acceptable. Even though most participants searched for product information online, they avoid online payment regardless of online purchase made in Thailand or overseas. For example, to make a purchase overseas, they will ask their friends overseas to buy the products for them instead of asking the sellers to ship directly to Thailand because shipping cost is expensive and postal system is not as reliable as developed countries. Moreover, most of the participants buy from Thai websites rather than foreign websites. When buying in Thailand, most participants prefer to call sellers (website owners) in Thailand for additional information and to hear their tone of voice to ensure the trustworthiness of sellers. Hence, purchase behavior of most participants is different from conventional online shoppers. Once they decided to purchase the products, most participants used bank transfer or cash (in case of face to face transaction with sellers) and only a few participants used credit cards. Their buying process indicates that there is a high concern for risks associated with buying online. Consequently, online shoppers tend to find alternative ways such as word of mouth communication to reduce their perceived risks. The results from the focus group also indicated the use of credit cards and security as the first and most important issue considered by the buyers, followed by the leakage of personal information, lack of trust on sellers, long waiting time for merchandise delivery, lack of merchandise trial, and cheating problems such as delivery of the merchandises which are different from what the sellers claimed or showed on the web. The findings from the focus groups in Thailand indicated the importance of word of mouth communications and marketing related factors (product, pricing) in the buying decision. More importantly, the results also show how they reduced perceived risks through personal interaction with online sellers/retailers. Hence, the following conceptual framework was developed based on the results from focus groups and hypotheses development. Figure 1. Conceptual framework Perceived Risk H1 Word of Mouth communication Traditional Online H2 H1 P Attitude towards online H3 shopping Online shoppers Non-online shoppers H4 Marketing related factors Product Complexity Price Promotion H5 Personal interaction with Salesperson 4. Questionnaire Design The final data collection process mainly focused on quantitative technique due to the nature of the research which examines the relationship between variables and wants to generalize the findings based on an acceptable sample size of respondents. A structured survey was chosen as it provides quick, relative inexpensive, efficient and accurate means of assessing information about the respondents (Zikmund, 2003). Based on the literature review and results from three focus groups, a four-page questionnaire, which consisted of three main parts covering 51 questions, was developed for this study. It took about 15-20 minutes for each respondent to complete the questionnaire. The first part covered the general information regarding the behavior of online and non-online shoppers. The second part addressed perceived risk, word of mouth communications, attitude toward online shopping, marketing related variables and personal interaction between sellers and buyers. The last part was about the personal information about the respondents and their internet behaviors. The survey questionnaire included a cover letter and a copy of the questionnaire. A 7 point Likert scale was used in the questionnaire due to its popularity and being easy to administer (Maxim, 1999; Zikmund, 2003). Most questions in the questionnaire were in the form of a statement and the respondents were asked to indicate their attitudes by rating how strongly they agree or disagree with the statements. The questionnaire was first developed in English and translated into Thai language by a Thai graduate from Business English Faculty. In order to ensure the accuracy of the questionnaire translation, a researcher at ABAC Poll and two colleagues checked the translation of questionnaires in Thai. They not only gave comments on the translation of the questionnaire but also the format and logical flow of the questions, and the questionnaire was adjusted accordingly. 5. Pretest The Pretest was conducted to detect ambiguity or bias in the questions and to ensure that respondents understood the questionnaire, and were familiar with terms used in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was pretested with a sample size of 100 respondents using convenience sampling in February, 2010. The majority of the respondents (46%) were male and 73% of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree. In addition, 46% of them were between 18 to 23 years old. Reliability analysis was performed on the main variables such as word of mouth communication, consumer attitude toward online shopping, marketing-related characteristics, perceived risk and personal interaction between sellers and buyers. The results of the reliability analysis indicated that Cronbach alpha value was higher than 0.7. 6. Research Methodology Quota sampling was employed to have a good representative of population and grouped based on both online shoppers and non-online shoppers, male and female of the internet users and age group reflecting the proportion of Bangkok population. According to the Nielsen (Thailand) report of 2008, 61% of Thai internet users (13.4 million users) had used the internet to make a purchase. Among the internet users, 72.5% of them were female. Field researchers were assigned to gather the data from 1185 respondents consisting of 716 online shoppers (60%) and 469 non-online shoppers (40%) to represent the population of internet users in Thailand. The online shoppers sample was further divided based on the gender (70% female and 30% male) and age group to ensure the representative of population. According to a survey conducted by National Electronic and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC) in 2006, the highest percentage of internet users (28%) in Thailand resides in Bangkok (Charnsiripinyo, 2008). Thus, the scope of study covered only Thai consumers in Bangkok. The data was collected in March 2010 in 14 Districts in Bangkok. The sample consists of those who are over 18 years old and has used internet at least once during the last three months. The self-administered questionnaire was distributed to the households, office workers and students in 14 districts and most of the questionnaires were collected during the lunch time. Based on the quota sampling, field researchers were assigned to collect the data from 1185 respondents but the total complete and usable responses were 1076.The data was collected with the support of ABAC Poll’s research team which consists of one researcher, one assistant researcher and 13 field researchers. 7. Data Analysis Data analysis involved several stages; Descriptive analysis, discussion of demographic characteristics of respondents, their internet usage behaviors and online shopping behavior, followed by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) which presents the factors resulting from the analysis together with Cronbach alpha values to indicate the reliability of each construct. Based on the results of EFA from total sample (consisting of both online shoppers and non-online shoppers), hypotheses were tested to investigate the differences between online shoppers and non-online shoppers. The sample size consists of 1076 usable responses (581 online shoppers and 495 non-online shoppers) and the majority of the respondents (61.8%) are female which roughly represent the population of women internet users in Thailand since 72.5% of internet users in Thailand were female (Pornwasin, 2010). The majority of the respondents are aged between 30-35 (24.3%), followed by the second largest group which is between 24-29 years old (23.4%), and 18-23 years old group (18.1%). Moreover, regarding the level of education, 68.5% of total respondents hold Bachelor’s Degrees, while 19.2% of them have high school education or lower than high school regulation and 9.6% of respondents are with Master’s or higher degrees. With regards to monthly household income level, the majority of respondents (37.9%) earn below 20,000 baht per month followed by 32.4% of respondents with monthly household income level of 20,001-40,000 baht and 12% of them with 40,001-60,000 baht. In addition, the sample represents the respondents from different walks of life as 42.2% of them are company employees and twenty percent are state employees, followed by students (18.9%) and business owners (17.7%). Hence, the demographic characteristics of the respondents represent people from different age groups, education levels, occupations and income levels. In addition, it is interesting that majority of the respondents (26.4%) have been using internet for more than 10 years and 46.5% of respondents spent one to three hours a day using internet and 25.7% of the respondents used internet 4 to 6 hours a day. Moreover 33.9% of online shoppers spent 2,001 (~ 70 US$) to 4,000 baht (~ 130 US$) per each online purchase while 28.6% of them used 1000 baht (~ 35 US$) or less for average online purchase. These are encouraging trends for online retailers in Thailand (see Table 1). Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of respondents and internet usage Demographic characteristics of respondents Category Respondents Online shoppers 54% Non-online shoppers 46% Education High school and lower 19.2% Bachelor’s degree 68.5% Master’s degree or higher Income Occupation Duration of internet usage percentage 9.6% Below Baht 20,000 (~ 670 US$) 37.9% Baht 20,001 (~ 670 US$) – 40,000 (~1,300 US$) 32.4% Baht 40,001(~1,300 US$) – 60,000 (~2,000 US$) 12% Baht 60,001 (~2,000 US$) – 80,000 (~2,600 US$) 9% Baht 80,001 (~2,600 US$) – 100,000 (~ 3,500 US$) 4.8% Baht 100,000 (~ 3,500 US$) and over 3.1% Student 18.9% Company employee 42.2% Government employee 20.4% Own business 17.7% Others 0.5% Less than one year 5.2% 1-3 years 18.3% 4-6 years 24.9 % 7-9 years 24.5 % 10 years or more 26.4 % Table 1 Continued Demographic Characteristics of respondents and internet usage Hours spent on internet per day Less than one hour 13.2 % 1-3 hours 46.5 % 4-6 hours 25.7 % 7-9 hours 9.7 % 10 hours or more 4.9% Average spending per transaction Bt 1,000 (~30 US$) or less 28.6 % Bt 1,001(~30 US$) – Bt 2,000 (~70US$) 33.9 % (answered by non-online shoppers only) Bt 2,001(~70US$) – Bt 4,000 (~130 US$) 22.0% % Bt 4,001(~130 US$) – Bt 7,000 (~200 US$) 6.2%% Bt 7,001 (~200 US$) and above 9.4% % Exchange rate: 1 US$ = 30.34 baht (September 8, 2011) The second part of the descriptive analysis shows that most respondents use the internet for entertainment purposes (77.1%) followed by communication (73.5%) and work purposes (71.4%). The respondents could give more than one answer for the above question. Out of a total of 1076 respondents, 581 of them are online shoppers and their main reason for buying online is due to convenience to buy online (67.5%) followed by ease of searching information (52%) and less time consuming (30.6%). The respondents were asked to give more than one answer for their reasons. On the other hand, non-online shoppers’ reason for not purchasing online is due to the security concern about payment system (46.7%) as well as their distrust on product quality (38.8%) and inability to see the products before purchase (29.7%). The results also show that 45.1% of respondents made their purchase one to 6 months ago, 20.4% less than a month ago and 19.3% made their purchase 7 to 12 months ago (See Table 2). This may be an encouraging trend not only for online retailers, but also for traditional retailers concerned about expanding their channels online. It is also interesting to note that the largest group of the respondents (21.4%) purchase clothes and accessories online, the second largest group (15.3%) purchases air tickets, and the third largest group purchases CD/DVD (11.7%), cosmetics (11.6%), and computers and accessories (10.9%) respectively. These findings are quite similar to The National Statistical Office's survey in 2009 which revealed that the popular products purchased via online trading in Thailand were fashion apparel, gems and jewelry, computer and electronic goods (Pratruangkrai, 2010) but the findings are quite different from Nielson Global Consumer Report (2010) in which 46% of global consumers surveyed in 2009 purchased books. According to the UNESCO, only 5 books were read per person per year in Thailand, while neighboring countries, such as Vietnam excel with 60 books and Malaysia with 40 books per person (UNESCO, 2011). Furthermore, the finding shows that the majority of online shoppers uses ATM or bank transfers (54.8%) in purchasing online while 27.7% of them use credit cards, and 6.2% used Pay Pal service for their last purchase. Among online shoppers, the check (4%) is the least used method for purchasing online. The results also indicate that 54.4% of Thai online shoppers prefer to purchase online from home, 36.3% from work place and 5.7% from internet café. These findings provide a better understanding of both non-online and online shoppers’ behavior in Thailand (see Table 2 for more detailed results). Table 2 General Information on Online Shoppers and Non-online shoppers Category Purpose of using internet of online shoppers and non-online shoppers (can give more than one answer) percentage Entertainment 77.1% Communication 73.5% Research 16.3% Networking 21.7% Work 71.4% Reading News 58% Playing games 44.1% Others 2.5% Reasons for not buying online I don’t have credit card 13.7% (answered by non-online shoppers) I don’t feel secure about the payment system 46.7% It takes some time to receive the product. 6.9% I don’t have a chance to see the product before making purchase 29.7% I’m not interested in online purchasing 31.3% I don’t trust the product quality 38.8% Others 1.4% Table 2 Continued General Information on Online Shoppers and Non-online shoppers Reason for buying online The price is cheaper to buy online 22.4% (answered by online shoppers) It is convenient to buy online 67.5% It is easier to search for the information 52% It is less time consuming 30.6% The product is not available at the traditional stores 23.1% Others 1.2% Product category Clothes/accessories 21.4% (answered by online shoppers) Cosmetics 11.6% Air tickets 15.3% CD/DVD 11.7% Mobile phone 5.7% Online game 5.5% Computer/hardware/accessories 10.9% Books 5.3% Car accessories/vehicle 5.7% Buddha pendant/amulet 1.1% Toys 2.1% Others 3.7% Type of payment Pay Pal 6.2% (answered by online shoppers) Credit cards Check ATM/Bank Transfer 27.7% 4% 54.8% M-pay (through mobile phone) 5.5% Others 1.7% Place of online purchase Home 54.4% (answered by online shoppers) Work Place 36.3% School/University 3.4% Internet Cafe' 5.7% Due to the large number of items on the survey instruments, the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was employed using SPSS to condense 26 variables into a smaller number of factors: word of mouth communication (9 items), personal interaction with sales person (7 items), and marketing related factors (10 items). The results of the EFA are presented in Table 3 to Table 5. As expected, the items measured word of mouth communication have been reduced to two factors, traditional and online word mouth communication explaining 69.1% of the total variance. The factor loadings of traditional and online word of mouth fell between the good range of 0.60 and 0.87 as loadings of 0.5 or greater were considered significant (Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black 1998). In addition, Cronbach’s alpha values of both word of mouth communications indicate good reliability (see Table 3). Table 3 Exploratory Factor Analysis for Word of Mouth Communication Factor Loading Word of Mouth Communication Traditional Online WOM WOM I receive the recommendation to buy online through friends or colleagues or family 0.77 I value the information I receive from friends or colleagues or family. 0.87 The information I receive from friends or colleagues or family is helpful for my decision making. 0.79 I always read reviews that are presented on the website. 0.77 The reviews presented on the website are helpful for my decision making. 0.85 The reviews presented on the website make me confident in purchasing the product. 0.86 I receive the recommendation to buy online from friends or colleagues or family through the internet. 0.60 I value the information I receive from friends or colleagues or family through internet. 0.66 The information I receive from friends or colleagues or family through internet are helpful for my decision making. 0.68 Reliability (standardized alpha coefficient) 0.83 0.89 Eigen value 5.1 1.1 Percentage of variance 56.7% 12.4% Total variance explained= 69.1% Even though the questionnaire items for consumers’ personal interaction with sales people were adopted from previous studies, they did not separate into personal interaction with sales person at traditional store or online store. The questions for personal interaction with sales person at online store were developed based on the consistent results of all focus groups’ desire to have personal interaction with online vendors in domestic market to reduce their perceived risks or to hear the tone of voice of the online vendors to boost their confidence in buying online. Here, EFA was conducted on seven items measuring personal interaction with the sales person which have been reduced into two groups; personal interaction with sales person at the traditional store and personal interaction with sales person at the online store, providing 73.9% of the total variance explained with the Eigen value of 3.9 and 1.3 respectively. Each factor has Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.86 each and the factor loading ranges from 0.73 to 0.89 indicating good reliability of items measured and acceptable factor loadings (See Table 4 for more details). Table 4 Exploratory Factor Analysis for personal interaction with salesperson Factor Loading Personal action with salesperson Traditional Online store Store I am satisfied with the level of service sales people provided at traditional store. 0.87 I am willing to discuss my needs in buying products with sales people at the traditional store. 0.88 I feel safe in my transactions with sales people at the traditional store. 0.81 If possible, I would like to send email to online retailers to inquire about the product before making purchase. 0.73 If possible, I would like to make a phone call to online retailers to inquire about the product before making purchase. 0.77 If possible, I would like to hear the voice of online retailers to ensure whether she/he is trustworthy. 0.82 If possible, I would like to have personal interaction with online retailers before making a purchase. 0.89 Reliability (standardized alpha coefficient) 0.86 0.86 Eigen value 3.9 1.3 Percentage of variance 55.3% 18.6% Total variance explained= 73.9% Another EFA was conducted on ten items representing marketing related factors. The results indicated three factors. However, the last factor which is supposed to measure the complexity of the products is not conceptually acceptable since they are loaded to other factors. Hence, the items related to complexity of the products were deleted from the study and EFA was conducted on 6 items that measured the perceived price and perceived online promotion. Table 5 indicates that two factors representing perceived online promotion and perceived price explained 74. 7% of the variance with Eigen value of 3.1 and 1.4 respectively. The factor loading ranges from 0.72 to 0.90 and these two factors have very good reliability value of 0.86 and 0.79 respectively as shown in Table 5. The rest of the constructs in the study are shown below in Table 6. The reliability of consumer attitude towards online shopping and perceived risks are 0.88 and 0.91 respectively. Table 5 Exploratory Factor Analysis for perceived online promotion and perceived price Factor Loading Perceived promotion The online retailers usually offer variety of promotion such as free sample, premium, bonus pack and coupons. 0.85 The online retailers usually offer more attractive promotion than traditional stores. 0.90 I purchase the products online because of the variety of promotion such as free sample, premium, bonus pack and coupons. 0.85 Perceived price The price for the online product is more expensive than traditional store. 0.88 The price for the online product is much higher than I expected. 0.88 What I would expect to pay for online product is high. 0.72 Reliability (standardized alpha coefficient) 0.86 0.79 Eigen value 3.1 1.4 Percentage of variance Total variance explained= 74.7 % 51.7% 23% Table 6 Exploratory Factor Analysis for consumer attitude and perceived risk Constructs and Items Consumer attitude towards online shopping Reliability (α) 0.88 Using the internet for shopping is enjoyable Using the internet for shopping is convenient Using the internet for shopping is interesting Using the internet for shopping is secure Using the internet for shopping is necessary Using the internet for shopping is a good idea. Perceived risk 0.91 I am not sure of internet payment system and hesitate to use them I do not feel safe exposing my personal information when I buy goods online. To buy a product from online retailers will be a high potential for loss. Online retailers’ product information is not generally trustworthy. 8. Research Findings and Managerial Implications The Independent sample t-test was used to determine the difference between online and nononline shoppers. Table 7 indicates that the mean values of all the constructs are significantly different between online shoppers and non-online shoppers except consumers’ preference for personal interaction at traditional stores. It shows that both online shoppers and non-online shoppers wish to have the same level of desire to have personal interaction with salesperson of the traditional stores (H5b). Hence, Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 are fully accepted, and H5 and H4 are partly accepted. H4 is partly accepted because as mentioned earlier in data analysis section, consumer perception towards complexity of product was dropped out from the study after EFA was performed. Table 7 indicates that online shoppers (mean = 4.5) have lower perceived risk towards online shopping than non-online shoppers (mean= 4.9). This result is consistent with previous studies of Chang and Chen (2008) and Kuhlmeier and Knight (2009) which found that perceived risk was an important factor in making online purchases. This study also found that online shoppers are more likely to engage in both traditional and online word of mouth communication than non-online shoppers. This finding was also supported by Duan, Gu and Whinston (2008) in which positive WOM has an impact on sales and repurchase intention of customers. In addition, online shoppers (mean = 4.7) have more positive attitude toward online shopping than non-online shoppers (mean = 3.5). Moreover, online shoppers find online promotion more attractive (mean = 4.3) than non-online shoppers (mean = 3.9) and tend to think that online shopping is a bit less expensive (mean = 4.2) than traditional shopping (mean = 4.3). In addition, online shoppers (mean = 4.5) are more likely to engage in personal interaction with online sales person than non-online shoppers (mean =4.3). Table 7 Independent sample t-test between online shoppers and non-online shoppers Online shoppers (N = 581) Non-online shoppers (N =485) Mean Mean Significance level Results H1: Perceived risk 4.5 4.9 0.00 Supported H2a:Traditional Word of Mouth 4.2 3.6 0.00 Supported H2b: Online Word of Mouth 4.4 3.7 0.00 Supported H3: Attitude towards online shopping 4.7 3.5 0.00 Supported H4a: Perceived online promotion 4.3 3.9 0.00 Supported H4b: Perceived price H5a: Personal interaction at traditional stores 4.2 4.3 0.02 Supported 4.6 4.6 0.75 H5b: Personal interaction at online stores 4.8 4.3 0.00 Composites Not supported Supported 1= strongly disagree, 7= strongly agree Thus, marketers should emphasize reaching the online and non-online shoppers and reducing their risks through social networking sites, and enhance promotional activities and pricing strategies to attract them to purchase more online. Moreover, online shoppers are also more likely to engage in personal interaction with online sellers/retailers than non-online shoppers. Hence, in order to encourage non-online shoppers to be online shoppers, both traditional and electronic word of mouth communication regarding lower price and online promotion should be targeted at them which is likely reduce their perceived risks and urge non-online shoppers to purchase online. Even if word of mouth communication does not always lead to online shopping, it will create brand awareness or awareness of online retailing. Moreover, online retailers should facilitate their websites to be convenient, enjoyable and accommodates personal communication with potential online shoppers if they wish to communicate to the retailers. Since now many online retailing websites starting to provide personal communication online, this must be an important trend for the future of online retailing. Furthermore, in order to have better understanding of online and non-online shoppers, crosstabulation test using chi-square was conducted to see whether gender, level of education, income level, years of internet usage and hours spent on internet could differentiate between online and non-online shoppers. The results indicate that there is no significant relationship between online and non-online shoppers in terms of gender and hours spent on internet. However, there are significant relationships in terms of income level, education level and years of internet usage. The results found that majority of online shoppers (34.8%) earns more than 40,000 baht a month (more than 1,300 US$) and majority of non-online shoppers (44.8%) makes 20,000 baht (700 US$) or less. In addition, 57.1% of online shoppers have been using internet for more than 6 years whereas 54.5% of non-online shoppers surfed internet for 6 years or less. Similarly, 23.4% of non-online shoppers have lower than bachelor degree education while only 16.6% of online shoppers accounts for the same category. Hence, the findings suggest that those who with higher level of education and higher income, and those who have used internet for more than 6 years are more likely to be online shoppers and online retailers should target their marketing activities at those groups. Furthermore, focus groups’ findings provide insightful information on online shopping behaviors of Thai consumers and focus groups’ results such as importance of personal interaction and word of mouth communications are strongly supported by survey results. Hence, this study also contributes to the importance of personal interaction with online retailers in differentiating between online shoppers and non-online shoppers in Thailand. This finding is different from previous studies in online shopping as most studies do not consider the importance of personal interaction between online shoppers and online retailers/sellers. This study also highlights the important role of both traditional and online WOM in explaining the difference between online and non-shoppers, extending the deeper understanding of online purchase behavior of consumers in Thailand. 9. Limitations and future research Like any other researches, the study has some limitations. Firstly, due to time and cost constraints, a cross-sectional study was conducted for this research. The study only looks at how word of mouth communication, personal interaction with salesperson, consumer attitude toward online shopping, their perceived price and online promotion in determining online and non-online shoppers at a particular period of time. However, market condition especially online retailing is changing rapidly and this study fails to examine how their attitude and behavior will change over time. Secondly, from a methodological point of view, although probability sampling would have been the ideal, quota sampling, non-probability sampling, was applied due to the difficult circumstances during the data collection process. However, the acquisition of a large sample size might compensate for the above weakness and might have better representation of the population. Finally, the data was collected only in Bangkok and surrounding areas making it difficult to generalize the findings to the overall Thai population. References Icek Ajzen, (1991) “The theory of planned behavior,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 50, 179-211. George Balabanis and Stefanos Vassileiou, (1999) “Some attitudinal predictors of homeshopping through the internet,” Journal of Marketing Management, 15 (June), 361-385. Caroline Bramall, Klaus Schoefer and Sally McKechine, (2004) “The Determinants and Consequences of Consumer Trust in E-Retailing: A Conceptual Framework,” Irish Marketing Review, 17 (1&2), 13-22. Tom J. Brown, Thomas E. Barry, Peter A. Dacin, and Richard F. Gunst, (2005) “Spreading the word: investigating antecedents of consumers' positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviours in a retailing context,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33 (2), 123138. Chalermpol Charnsripinyo (2008) “Measuring the Internet (User) Growth in Thailand,” National Electronic and Computer Technology Center (NECTEC), Thailand, November 18, 2008, http://www.thnic.or.th/doc/NTL-NECTEC.pdf, accessed on December 28, 2008. Arjun Chaudhuri, (2000) “A macro analysis of the relationship of product involvement and information search: The role of risk,” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 8 (1), 1-15. Hsin Hsin Chang and Su Wen Chen, (2008) “The impact of online store environment cues on purchase intention: Trust and perceived risk as a mediator,” Online Information Review, 32 (6), 818-841. Chadamas Chinmaneevong, (2009) “Online shopping taking off,” Bangkok Post, Business Section. Margy P. Conchar, George M. Zinkhan, Cara Peters and Sergio Olavarrieta, (2004) “An integrated framework for conceptualization of consumers’ perceived-risk processing,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(4), 418-436. Grahame R. Dowling and Richard Staelin, (1994) “A model of perceived risk and intended risk-handling activity,” Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 119-134. Wenjing Duan, Bin Gu and Andrew B. Whinston, (2008) “The dynamics of online word-ofmouth and product sales – An empirical investigation of the movie industry,” Journal of Retailing, 84 (2), 233-242. Lori Enos, (2001) “Can word-of-mouth save e-commerce? E-Commerce Times, May,” available at: www.ecommercetimes.com/story/9224.html. Brooke E. Foucault and Dietram A. Scheufele, (2002) “Web vs. Campus Store? Why students buy textbooks online,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19 (5), 409-423. Joseph F. Hair, Rolph E. Anderson, Ronald L. Tatham and William Black, (1998) Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th Ed., Prentice-Hall International, Inc. Martin G. Helander and Halimahtun M. Khalid, (2000) “Modeling the customer in electronic commerce,” Applied Ergonomics, 31, 609-619. Thorsten Henning-Thurau and Gianfranco Walsh, (2003) “Electronic Word-of Mouth: Motives for and Consequences of Reading Customer Articulations on the internet,” International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8 (2), 55-74. Morris B. Hirschman and Elizabeth C. Holbrook, (1982) “The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun,” Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (2), 132-140. Internet world Stats (2011) “Asia Internet Usage and Population,” http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats3.htm, accessed on September 7, 2011. IMAP, 2010, “Retail Industry Global report-2010,” http://www.imap.com, accessed on September 7, 2011. Jihyun Kim and Jihye Park, (2005) “A consumer shopping channel extension model: attitude shift toward the online store,” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 9 (1), 106-121. Jung-Hwan Kim, Minjeong Kim and Sharron J. Lennon, (2009) “Effects of web site atmospherics on consumer responses: music, and product presentation,” Direct Marketing: An International Journal, 3 (1), 4-19. David Kuhlmeier and Gary Knight, (2009) “Antecedents to internet-based purchasing: a multinational study,” International Marketing Review, 22 (4), 460-473. Dee Ann Larson, Brian Engelland and Ron Taylor, (2004) “Information search and perceived risk: Are there differences for in-home versus in-store shoppers?” Marketing Management Journal, 14(2), 36-42. Kittipong Laosethakul and William Boulton, (2007) “Critical Success Factors For E-commerce in Thailand: Cultural and Infrastructural Influences,” The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 30, 2, 1-22. Heejin Lim and Alan J. Dubinsky, (2004) “Consumers’ perceptions of e-shopping characteristics: an expectancy-value approach,” Journal of Services Marketing, 18 (7), 500-513. May O. Lwin and Jerome D. Williams, (2006) “Promises, promises: How consumers respond to warranties in internet retailing,” The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 40 (2), 236-260. Woranuj Maneerungsee, (2009) “Marketers target social sites,” Bangkok Post, Business Section. Paul S. Maxim, (1999) Quantitative Research Methods in Social Sciences, Oxford University Press. Vincent-Wayne Mitchell, (1999) “Consumer perceived risk: Conceptualizations and models,” European Journal of Marketing, 33 (1/2), 163-195. Tonita Perea y Monsuwe’, Benedict G.C. Dellaert and Ko de Ruyter, (2004) “What drives consumers to shop online? A literature review.” International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15 (1), 102-121. Nielson (2007) “Word of Mouth: The Most Powerful Selling Tool,” Nielson Global Survey, http://th.nielson.com/news, accessed on June 13, 2009. Nielson (2008) “Trends in Online Shopping,” A Global Nielson Consumer Report, February, 2008. Nielson (2010) “Global Trends in Online Shopping,” Nielson Global Consumer Report, June, 2010. Do-Hyung Park, Jumin Lee and Ingoo Han, (2007) “The Effect of On-Line Consumer Reviews on Consumer Purchasing Intention: The Moderating Role of Involvement,” International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 11 (4), 125-148. Chanthika Pornpitakpon, (2000) “Trade in Thailand: A Three-way Cultural Comparison,” Business Horizon, March-April, 61-69. Asina Pornwasin, (2008) “Thai e-commerce reaches 427 billion baht,” The Nation, November 18, 2008. Asina Pornwasin, (2010) “Women Surf Internet more than men,” The Nation, February 17, 2010. Petchanet Pratruangkrai, (2010) “Red-shirt rallies boost e-commerce”, The Nation, March 22, 2010. Kristy E. Reynolds and Mark J. Arnold, (2000) “Customer Loyalty to the Salesperson and the Store: Examining Relationship Customers in an Upscale Retail Context,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 20 (2), 89-98. Michael J. Ryan, (1982) “Behavioral intention information: the independency of attitudinal and social influence variables,” Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 263-278. Jagdish Sheth and Atul Parvatiyar, (1995) “Relationship Marketing in Consumer Markets: Antecedents and Consequences,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (4), 255271. Jagdish N. Sheth and M. Venkateson, (1968) “Risk Reduction Process in Repetitive Consumer Behavior,” Journal of Marketing Research, 5 (3), 307-310. Soyeon Shim, Mary Ann Eastlick, Sherry L. Lotz and Patricia Warrington, P (2001) “An online prepurchase intentions model: the role of intention to search”, Journal of Retailing, 77 (3), 397-416. Soyeon Shim and Kittichai Watchravesringkan, (2003) “Information search and shopping intentions through Internet for apparel products,” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 21 (1), 1-7. Peter Spiller and Gerald L. Lohse, (1998) “A classification of Internet retail stores,” International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 2 (2), 29-56. Tiffany Stewart, Becky Wettstein and Dennis Bristow, (2004) “The Internet as a Shopping/Purchasing Tool: An Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Internet Commerce, 2 (4), 87-102. Tao Sun, Seounmi Youn, Guohua Wu and Mana Kuntaraporn, (2006) “Online Word-of-mouth (or Mouse): An explanation of its Antecedents and Consequences,” Journal of ComputerMediated Communication, 1104-1127. James W. Taylor, (1974) “The Role of Risk in Consumer Behavior,” Journal of Marketing, 38 (2), 54-60. UNESCO ( 2011) “Thai people to read more,” http://www.unescobkk.org/education/news/article/thai-people-to-read-more/ accessed on September 9, 2011. Robert A. Westbrook, (1987) “Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase process,” Journal of Marketing Research, 24, 258-270. William G. Zikmund, (2003) Business Research Methods, 7th Ed., Thomson, South Western. Acknowledgement: We would like to express our appreciation to Dr. Noppadon Kannika, director of the ABAC Poll, and his research team, Ms, Natenapist La-iad, deputy director, Ms. Wanwisa Charoennan, Mr. Subhachai Yodkhaek, Ms. Brenda Martin, Mr. Panupong Dintordan and 13 field researchers for their advice and support in moderating focus groups and data collection. We would also like to thank our chairperson, Dr. Suwanna Kowathanakul, and colleagues for their support and comments on our questionnaire.