Japanese Internment DBQ

advertisement

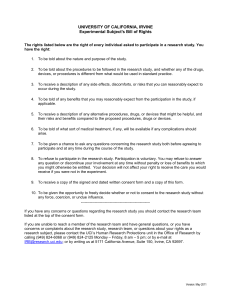

US History – Japanese Internment Document-Based Question California History Standard 11.7.5 Discuss the constitutional issues and impact of events on the U.S. home front, including the internment of Japanese Americans (e.g., Fred Korematsu v. United States of America) and the restrictions on German and Italian resident aliens; the response of the administration to Hitler’s atrocities against Jews and other groups; the roles of women in military production; and the roles and growing political demands of African Americans. Common Core State Standard Reading Key Ideas and Details 1. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole. 2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas. Craft and Structure 4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including analyzing how an author uses and refines the meaning of a key term over the course of a text (e.g., how Madison defines faction in Federalist No. 10). 6. Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence. Integration of Knowledge and Ideas 7. Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem. 8. Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information. 9. Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources. Writing Text Types and Purposes 1. Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content. 2. Write informative/explanatory texts, including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/ experiments, or technical processes. Production and Distribution of Writing 4. Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. 5. Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience. Research to Build and Present Knowledge 8. Gather relevant information from multiple authoritative print and digital sources, using advanced searches effectively; assess the strengths and limitations of each source in terms of the specific task, purpose, and audience; integrate information into the text selectively to maintain the flow of ideas, avoiding plagiarism and overreliance on any one source and following a standard format for citation. 9. Draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research. Range of Writing 10. Write routinely over extended time frames (time for reflection and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences. UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Background The attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 took Americans by surprise. Despite a firm policy of isolationism, they catapulted themselves into the Second World War. In addition to sending their armed forces into the battles in the Pacific Theater, they also took actions at home which they believed would protect them from further attack. The most notable of these was the internment of thousands of citizens of Japanese descent, mostly along the Pacific coast, in forced relocation camps. Prompt Was the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II justified? Write a five paragraph essay utilizing at least four of the given documents. Tasks Include an original claim that organizes your essay Use at least four documents Use multiple pieces of evidence in each paragraph to support your argument Include a counterargument Include a conclusion Write in complete sentences Write in the third person Sources Text Memoir from internment “500 Tanforan Japs to Utah” “Youth Accepts Challenge…” “Letter of the Week” “To the Editor” Excerpts from "Issei, Nissei, and Kibei." Images “Are we Americans again?” UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Document A Found online: http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB162/19.pdf UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Document B From: the University of California UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Document C From: The University of California UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Document D From: the University of California , “Are we Americans again?”, by Estelle Ishigo, Estelle, created between 1942 and 1945 UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Document E From the University of California UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Document F To the Editor: Never before have I taken a pen in hand and written to a newspaper editor but "there comes a time in every man's life," I suppose. I have been watching with growing disgust the efforts of some misguided politicians in California to create an issue out of the Japanese-American problem… I can see what the Japanese-Americans in our armed forces are fighting and dying for. They are not only fighting for America but they are fighting for the right of their families to live side by side with the more fortunate races that have made our nation the great nation it is today. They are fighting for tolerance. They are fighting to prove they and their families had nothing to do with December 7, 1941. They had no axe to grind and a lot of them are giving their lives to prove it. Probably their last thoughts, as they fall mortally wounded, far from their homes in Hawaii, are, "Well, perhaps this will prove we are Americans."… I speak only for myself as I write this letter. I don't know what my fellow soldiers think on the subject, as I have never brought the subject into open discussion, but knowing my fellow soldiers as I do, I think they would certainly be against those hair-brained schemes of radicals who have nothing better to do during this war than to sit around thinking of ways and means of persecuting a minority… Why judge a whole race of people and refuse them the right to return to their homes in the western states after the war just because of what a disloyal, small minority of their race has done? No one in this war is persecuting the German-Americans and Italo-Americans, and there is no reason in the world why they should, so why impose a penalty, after the war, upon the Japanese-Americans? When I meet a Japanese-American on the street in the same uniform as my own, I know he is fighting two wars, our war and his own private war for his people against public opinion and racial discrimination. I am sorely tempted to salute him and say, "Thou art a better man than I am, Gunga Din."… I am not of Japanese blood but I would be proud to have a transfusion from one of those boys on the Italian front. DUDLEY C. RUISH, Pfc. USA FROM "SOMEWHERE IN THE PACIFIC" PUBLISHED IN THE STAR-BULLETIN, HONOLULU, T. H. (archived by the University of California) UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/ Document G Excerpts from a pamphlet that originally appeared in Fortune magazine, April, 1944, under the title "Issei, Nissei, and Kibei.", archived at the University of California The displaced Japanese-Americans ... There are three different types of barbed-wire enclosures for persons of Japanese ancestry. First there are the Department of Justice camps, which hold 3,000 Japanese aliens considered by the F.B.I. potentially dangerous to the U.S. These and these alone are true internment camps. Second, there are ten other barbed-wire enclosed centers in the U.S., into which, in 1942, the government put 110,000 persons of Japanese descent (out of a total population in continental U.S. of 127,000). Two-thirds of them were citizens, born in the U.S.; one-third aliens, forbidden by law to be citizens. No charges were brought against them. When the war broke out, all these 110,000 were resident in the Pacific Coast states—the majority in California. They were put behind fences when the Army decided that for "military necessity" all people of Japanese ancestry, citizen or alien, must be removed from the West Coast military zone. Within the last year the 110,000 people evicted from the West Coast have been subdivided into two separate groups. Those who have professed loyalty to Japan or an unwillingness to defend the U.S. have been placed, with their children, in one of the ten camps called a "segregation center" (the third type of imprisonment). Of the remainder in the nine "loyal camps," 17,000 have moved to eastern states to take jobs. The rest wait behind the fence, an awkward problem for the U.S. if for no other reason than that the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were severely stretched if not breached when U.S. citizens were put in prison. Back in December, 1941, there was understandable nervousness over the tight little Japanese communities scattered along the West Coast… authorities were besieged with telephone calls from citizens reporting suspicious behavior of their Oriental neighbors…Every rumor of Japanese air and naval operations…helped to raise to panic proportions California's ancient and deep antagonism toward the Japanese-Americans… The Associated Farmers in California had competitive reasons for wanting to get rid of the JapaneseAmericans who grew vegetables at low cost on $70 million worth of California land. California's land laws could not prevent the citizen-son of the Japanese alien from buying or renting the land. In the cities, as the little Tokyos grew, a sizable commercial business came into Japanese-American hands— vegetable commission houses, retail and wholesale enterprises of all kinds. It did not require a war to make the farmers, the Legion, the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West, and the politicians resent and hate the Japanese-Americans. The records of legislation and press for many years indicate that the antagonism was there and growing. War turned the antagonism into fear, and made possible what California had clearly wanted for decades—to get rid of its minority... The greatest forced migration in U.S. history resulted. UCI History Project, 2012 | 431 Social Science Tower | Irvine, CA | 92697-2505 http://www.humanities.uci.edu/history/ucihp/