assignment-2-eddx901-for-blog

advertisement

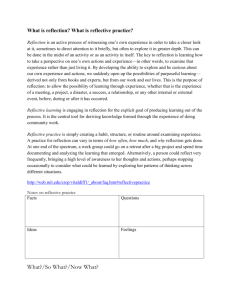

EDDX901: DOCTOR OF EDUCATION COURSEWORK Coordinator: PROFESSOR KWOK-WING LAI ASSIGNMENT 2: AN ESSAY ON THE THEORIES AND PRACTICES OF REFLECTIVE AND RESEARCH PRACTITIONERS Name: Merrolee Penman 1 Occupational therapists are “concerned with promoting health and well being” (World Federation of Occupational Therapy, 2004, para. 1). Reflection and research are considered to be some of the most important tools in the occupational therapy toolbox. However, while occupational therapists can articulate the value of reflection, they are less confident about using research findings to guide their practice, let alone being a researcher (Forsyth, Mann, & Kielhofner, 2005; Taylor, 2007). In Aotearoa/New Zealand, all entry-level practitioners are expected to be competent in reflective practice, to understand the research process, and contribute to the occupational therapy body of knowledge (Occupational Therapy Board of New Zealand [OTBNZ], 2000). While the OTBNZ lists these competencies separately, in this essay it will be argued that the research and reflective processes are so similar, that practitioners should consider the role of reflective and researching practitioner as one and the same. Integrating the roles into one, is a potential solution to address the increased theory-practice divide identified by leaders in the profession (Forsyth et al., 2005; Peloquin & Abreu, 1996). Research, as defined in the field of healthcare, is “a systematic and principled way of obtaining evidence (data, information) for solving health care problems” (Polgar & Thomas, 2000, p. 3). Occupational therapy research informs the knowledge base practitioners use to solve the myriad complex and social situations faced daily (Kielhofner, 2006). To provide what is needed for effective problem solving, Higgs, Andresen and Fish (2004) argue that occupational therapy practitioners, educators and researchers share a professional responsibility to use the essential skills of reflection, theorising and researching in order to make explicit practice knowledge; appraise knowledge use; and continually improve practice knowledge for the use of all. 2 Reflection at it’s simplest is ‘thinking’ (Cross et al., 2006) or making visible, what is invisible (de Cossart & Fish, 2005). Most agree that reflection is thinking with a purpose, a systematic process of linking ideas in order to solve a problem (Hatton & Smith, 1995), “analys[ing] the self in relation to what has happened or is happening and mak[ing] judgements regarding this” (Driscoll, 2007, p. 29). The levels to which this analysis occurs can vary, according to Valli (1997) who identified five types of reflection. These include technical (matching performance against external guidelines); reflection-in and on-action (basing decisions on unique situations); deliberative reflection (comparing personal viewpoints with research findings); personalistic reflection (being guided by one’s inner voice and the voices of others); and critical reflection (considering the social, moral and political issues). Using any one of these types of reflection, the practitioner is “seeking to uncover rigorously and understand and articulate the relationship between one’s visions, values and beliefs, and one’s thought, knowledge and action, in reference to specific examples of one’s own practice” (de Cossart & Fish, 2005, p. 75), thus delving deeply to understand what informs their decision making. While Dewey and Habermas are acknowledged as the modern day fathers of reflection (de Cossart & Fish, 2005; Hatton & Smith, 1995), Schön is known for further developing Dewey’s ideas (Dahlgren, Richardson, & Kalman, 2004; Hatton & Smith, 1995; Jay, 2004; Zeichner & Tabachnick, 2001). Schön (1983) coined the terms reflection-in and on-action, to describe the cycles of acting and thinking that professionals use to develop tacit or practice knowledge (Driscoll, 2007; Fleming & Mattingly, 1994). Reflection-in-action is the “conscious thinking and modification” (Hatton & Smith, 1995, p. 34) that occurs in the here-and-now as the therapist ‘thinks on their feet’, while reflection-on-action (Bolton, 2005; Driscoll, 2007; Jay, 2004) 3 occurs after the event; the pausing to see how it went-to ask what went well, what didn’t and what could be changed for next time” (Jay, 2004, p. 12) Reflection can also be future-oriented. Termed as either reflection-beforeaction, (Driscoll, 2007), reflection for action (Killion and Todnem as cited in Jay, 2004), preparatory reflection (Cowan as cited in Cross et al., 2006) or anticipatory action (Loughran, 1996), the purpose is “not so much to revisit the past or to become aware of the metacognitive process one is experiencing … but to guide future action (the more practical purpose)” (Jay, 2004, p. 13). The concept of future-oriented reflection does not appear to be as well developed as Schön’s (1983) cycles of reflection. The reasons for this are not clear, but it may be that forward planning is considered less an aspect of reflection and more a skill in planning, with the practitioner drawing from the learning they have gained through the cycles of reflection-in-action or reflection-on-action. Schön’s cycles have attracted some critique (Dahlgren et al., 2004) but are still considered “seminal for those who educate professionals in the practice setting” (de Cossart & Fish, 2005, p. 80) Irrespective of the models utilised, there is some agreement as to the practices of reflective practitioners. Reflective practitioners systematically investigate their experiences seeking answers to complex issues (de Cossart & Fish, 2005) arising out of day-to-day practice. Reflective practitioners are attentive not only to situations that occur in their practice, but also to the idiosyncrasies, asking ‘what didn’t I pay attention to at the time that I should have?’(Bolton, 2005; Dahlgren et al., 2004). In being this attentive, the reflective practitioner is self-evaluative and critical (Dahlgren et al., 2004; de Cossart & Fish, 2005; Wlodarsky & Walters, 2006), using the route of 4 spirited enquiry (Bolton, 2005) to make explicit, then appraise and further develop their practice knowledge (Higgs et al., 2004). Learning gained through the reflective process can be pragmatic, as in the practitioner identifying actions that they may use in the next problematic situation. However, when a practitioner critically reflects (Valli, 1997), alignment between current practice and espoused values is tested (Duggan, 2005) with deeper understanding of the personal and professional self the result (de Cossart & Fish, 2005; Duggan, 2005; Johansson & Bjorklund, 2005). Outcomes of engaging in reflection include the development of soft skills such as emotional intelligence, selfregulation, and therapeutic use of self (Zimmerman, Bryam Hanson, Stube, Jedlicka, & Fox, 2007), with Kinsella (2001) stating that reflection is effective for the development and enhancement of professional practice. In summary, engaging in reflection is “at the heart of what it means to be professional” (Goodson, 2003, p. 129), ensuring that practitioner decision-making is not ruled by tradition, authority or circumstance, but is informed by a person’s professional knowledge base (Parsons & Brown, 2002; Zeichner & Tabachnick, 2001). This professional knowledge base is created through blending three types of knowledge – propositional, generated through research and scholarship; personal, generated through life experiences; and professional craft, generated through professional experience (Titchen, McGinley, & McCormack, 2004). While reflection is considered essential in the creation of professional craft and personal knowledges, others (Higgs et al., 2004; Kinsella, 2001) believe that the reflective process is also integral to the creation of propositional, or the theoretical knowledge that is “created to explain, explore or extend practice” (Higgs et al., 2004, p. 52). 5 Traditionally, academics have been held responsible for the creation and dissemination of propositional knowledge, which practitioners were expected to absorb and then apply (Fox, Martin, & Green, 2007; Hargreaves, 2007; Robinson & Lai, 2006; Zeichner & Noffke, 2001). These two roles, one to create, and the other to apply, have prevailed in the occupational therapy profession. Recently, Kielhofner (2005b), a leading occupational therapy researcher and academic has challenged this duality, drawing the profession’s attention to the notion of a scholarship of practice. This approach assumes that there is value in practitioners, the ‘knowledge users’, partnering with the scholars and researchers, the ‘knowledge creators’, to collaboratively advance the profession’s propositional knowledge. The effectiveness of this approach in occupational therapy is still under investigation; therefore attention is directed towards the educational literature for the second part of this essay which focuses on the value of and importance of ‘knowledge users’ also being researching practitioners. In education, a researching practitioner is a teacher who systematically examines their practices, investigating the assumptions on which their practice is constructed (Fox et al., 2007; Garbett, 2004). Middlewood, Coleman and Lumby (1999) suggest that the changes that occur through the research process are transformative for all involved, as new understandings are reached. While researching practitioners can legitimately use a range of methodologies, specific traditions have arisen out of the researching practitioner literature. Zeichner and Noffke (2001) outline five major research traditions (cooperative action research, teacher-as-researcher/participatory action research, teacher researcher movement, self-study research, participatory research) that have informed the design 6 and implementation of practitioner research. Action research provided the base from which, over the last 50-60 years (Parsons & Brown, 2002), the other four traditions have developed. In each tradition, the action orientation (solving issues arising from practice) (Parsons & Brown, 2002), and practice focus (Fox et al., 2007) is aimed at improving educational practices, through the development of context-specific solutions (Dadds, 1998; Robinson & Lai, 2006; Zeichner & Noffke, 2001). The implementers of the research can be individual practitioners (academic or teacher), or collaborative groups consisting of teachers and academics (Dadds, 1998; Zeichner & Noffke, 2001). Regardless of who is involved, a cyclic or linear systematic process is used. Another aim of practitioner research is the creation of change through the collective actions of concerned practitioners, in relation to larger social or political issues. In addition, Robinson and Lai (2006) suggest that practitioner research is a form of effective professional development, the learning from which provides a strong foundation to ensure that improvements in teaching and learning made, are sustainable. Although positive outcomes of practitioner research are evident, there has been much debate in the educational literature as to whether practitioners have the ability to undertake research, and more importantly whether the findings presented are even valid (Clayton et al., 2008; Dadds, 1998; Middlewood et al., 1999). Despite these criticisms, practitioner research is growing, albeit slowly (Hancock, 2001). Some of the barriers to whole-scale adoption include working conditions that leave little time to plan and implement research, and a mismatch between traditional research methodologies and the questions teachers are interested in researching (Hancock). 7 The slow uptake of research by educational practitioners is surprising, given that the practices of research practitioners appear very similar to that of reflective practitioners. In both roles, the practitioner, motivated by the desire to find answers to their questions, engages in spirited enquiry, alone or with others, which ultimately leads to professional and personal learning (Dadds, 1998; Parsons & Brown, 2002). In reviewing their practice, reflective practitioners and researching practitioners are selfevaluative and critical, using reflection to develop in-depth understandings that promote or generate changes at the individual, school or wider community level. There seems to be little that distinguishes the practices of the reflective practitioner and the researching practitioner. Perhaps the key difference is in the responsibility of the researcher to share their findings with a wider audience than just the individuals, or groups involved in the research. However, it is also argued that reflective practitioners should also share the outcomes of their reflections with a wider audience. Certainly this is the point made by Higgs and her colleagues (2004), who argue convincingly that reflective practice is essential in the production of professional knowledge, and that the creation of professional knowledge is something all practitioners should aspire to, not left to the scientists or scholars of the profession. Robinson and Lai (2006) caution against the allocation of research to academics only, suggesting this is one reason for the theory-practice divide identified in the literature. Instead, they argue that the roles overlap, with an educator being both a reflective and researching practitioner. This view is also supported by Campbell, McNamara and Gilroy (2004) who suggest that the reflective practitioner is a “researcher, researching their everyday practice as they practise” (p. 10), with 8 Roulston, Legette, Deloach and Pitman (2005) and Fox et al. (2007) arguing that critical reflection is an integral part of the research process undertaken by researchers. Therefore, while the topics of reflective practitioner and researching practitioner are often introduced and discussed separately in textbooks, it would seem there is much to gain in combining the roles. The evidence would suggest that educators can, and should be reflective researching practitioners. In combining the roles, individuals will be excellent practitioners, knowledgeable about the processes they use to further their personal and professional craft knowledge, and confident researchers able to meet their professional responsibilities of building, testing and disseminating of the profession’s propositional knowledge (Higgs et al., 2004). Drawing from perspectives offered by a range of health and educational scholars, the argument is made in this essay, that an occupational therapist can be both a reflective practitioner and a researching practitioner, with Fox et al (2007) maintaining that “it is through practitioners researching their own practice, their own service and their own profession, that positive change will happen in the public services” (p. 201). Kielhofner and colleagues (Hammel, Finlayson, Kielhofner, Helfrich, & Peterson, 2001) believe that the route to developing practitioner researchers is through a scholarship of practice. Introduced in 2001 at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the first example of a scholarship of practice included only academics and their students, with local occupational therapists having a secondary, or much lesser role of data collectors and/or providers of intervention services (Hammel et al.). The power to shape the research lay with the academics and scholars (Kielhofner, 2005a). Over the next four years, the premises of the scholarship of practice were further explored 9 and by 2005, the early power imbalance had been addressed with clear direction as to the essential nature of power sharing between the academic/scholar and the practitioner (Forsyth et al., 2005; Kielhofner, 2005a, 2005b). Kielhofner (2005b) states, “those who ultimately … use the knowledge must be partners in its generation” (p. 10). The year 2005 saw the publication of nine articles in a focused issue of Occupational Therapy in Healthcare. The authors of these nine articles all used scholarship of practice, as proposed by Kielhofner and his colleagues, to address specific practice questions, using one of the traditions of action research (Zeichner & Noffke, 2001). Combined together, the evidence from all nine articles suggests that the scholarship of practice appeared to be an effective way of developing the knowledge and skills of both researcher and practitioner. Through their involvement in a scholarship of practice, occupational therapists thought more deeply about practice issues using deliberative, personalistic and critical reflection (Valli, 1997) and were more confident to use their research knowledge and skills (Finlayson, Shevil, Mathiowetz, & Matuska, 2005; Forsyth et al., 2005; Kielhofner et al., 2006). The outcomes of the collaborative projects have led to the development of clinically useful outcome measures (Forsyth et al., 2005), or clinically useful interventions (Finlayson et al., 2005). Transformation and empowerment of both academics/scholars and occupational therapists was also evident (Kielhofner et al., 2006). The scholarship of practice framework appears to be a promising mechanism for not only assisting to bridge the theory-practice divide, but for also ensuring that members of the profession not only see themselves as excellent reflectors, but also confident researching practitioners. 10 To conclude, occupational therapists are required to be competent reflectors, and consumers/producers of research, however in Aotearoa/New Zealand, these competencies are separated. This poses a substantial risk, as the occupational therapist continues to develop their skills in reflection and reading research, but often leaves research to the researchers. This essay argues that there is much value for the practitioner and ultimately the clients they serve, by integrating these roles. Higgs et al’s (2004) vision that all will share the responsibility of reflecting, theorising and researching in order to make explicit their practice knowledge is achievable through Kielhofner and colleagues (Hammel et al., 2001) scholarship of practice. However, to achieve what these two visionaries have proposed will require those who have remained separate, to come together in a spirit of collaboration. It is only when this has occurred, and when practitioners and academics have created together, that occupational therapists will be able to legitimately claim the role of reflective researching practitioner. 11 References Bolton, G. (2005). Reflective practice. Writing and professional development. London: Sage Publications. Campbell, A., McNamara, O., & Gilroy, P. (2004). Practitioner research and professional development in education. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. Clayton, S., O'Brien, M., Burton, D., Campbell, A., Qualter, A., & Varga-Atkins, T. (2008). 'I know it's not proper research, but...': How professionals' understandings of research can frustrate its potential for CPD. Educational Action Research, 16(1), 73-84. Cross, V., Moore, A., Morris, J., Caladine, l., Hilton, R., & Bristow, H. (2006). The practice-based educator. A reflective tool for CPD and accreditation. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. Dadds, M. (1998). Supporting practitioner research: a challenge. Educational Action Research, 6(1), 39 - 52. Dahlgren, M. A., Richardson, B., & Kalman, H. (2004). Redefining the reflective practitioner. In J. Higgs, B. Richardson & M. A. Dahlgren (Eds.), Developing practice knowledge for health professionals (pp. 15-34). Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann. de Cossart, L., & Fish, D. (2005). Cultivating a thinking surgeon. New perspectives on clinical teaching, learning and assessment. Harley, Shrewsbury: tfm Publishing. Driscoll, J. (2007). Practicing clinical supervision. A reflective approach for healthcare professionals. Edinburgh: Balliere Tindall Elsevier. Duggan, R. (2005). Reflection as a means to foster client-centred practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(2), 103-112. Finlayson, M., Shevil, E., Mathiowetz, V., & Matuska, K. (2005). Reflections of occupational therapists working as members of a research team. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 52(2), 101-108. Fleming, M. H., & Mattingly, C. (1994). Giving language to practice. In C. Mattingly & M. H. Fleming (Eds.), Clinical reasoning: Forms of inquiry in a therapeutic practice (pp. 3-21). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. Forsyth, K., Mann, L. S., & Kielhofner, G. (2005). Scholarship of practice: making occupation-focused, theory-driven, evidence-based practice a reality. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(6), 260-268. Fox, M., Martin, P., & Green, G. (2007). Doing practitioner research. London: Sage Publications. 12 Garbett, R. (2004). The role of practitioners in developing professional knowledge and practice. In J. Higgs, B. Richardson & M. A. Dahlgren (Eds.), Developing practice knowledge for health professionals (pp. 165180). Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann. Goodson, I. F. (2003). Professional knowledge, professional lives. Studies in education and change. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press. Hammel, J., Finlayson, M., Kielhofner, G., Helfrich, C. A., & Peterson, E. (2001). Educating scholars of practice: an approach to preparing tomorrow's researchers. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 15(1/2), 157-176. Hancock, R. (2001). Why are class teachers reluctant to become researchers? In J. Soler, A. Craft & H. Burgess (Eds.), Teacher development. Exploring our own practice (pp. 119-132). London: Paul Chapman Publishing. Hargreaves, D. H. (2007). Teaching as a research-based profession: possibilities and prospects (The Teacher Training Agency Lecture 1996). In M. Hammersley (Ed.), Educational research and evidence-based practice (pp. 3-17). Los Angeles: Sage. Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching & Teacher Education, 11(1), 44-49. Higgs, J., Andresen, L., & Fish, D. (2004). Practice knowledge - its nature, sources and contexts. In J. Higgs, B. Richardson & M. A. Dahlgren (Eds.), Developing practice knoweldge for health professionals (pp. 51-70). Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann. Jay, J. K. (2004). Quality teaching. Reflection as the heart of practice. Oxford: Scarecrow Press. Johansson, A., & Bjorklund, A. (2005). Uniting theory and practice in occupational therapy students' clinical examinations: a pilot study. Practice Development in Health Care, 4(2), 96-107. Kielhofner, G. (2005a). Research concepts in clinical scholarship. Scholarship and practice: bridging the divide. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 59(2), 231-239. Kielhofner, G. (2005b). A Scholarship of Practice Creating Discourse Between Theory, Research and Practice. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 19, 716. Kielhofner, G. (2006). The necessity of research in a profession. In G. Kielhofner (Ed.), Research in occupational therapy. Methods of inquiry for enhancing practice (pp. 1-9). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co. 13 Kielhofner, G., Castle, L., Dubouloz, C.-J., Egan, M., Forsyth, K., Melton, J., et al. (2006). Participatory research for the development and evaluation of occupatioanl therapy: Researcher-practitioner collaboration. In G. Kielhofner (Ed.), Research in occupational therapy. Methods of inquiry for enhancing practice (Vol. 643-655). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis. Kinsella, E. A. (2001). Reflections on... Reflections on reflective practice. The Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(3), 195. Loughran, J. J. (1996). Developing reflective practice: learning about teaching and learning through modelling. London: Falmer Press. Middlewood, D., Coleman, M., & Lumby, J. (1999). Practitioner research in education: Making a difference. London: Paul Chapman Publishing. Occupational Therapy Board of New Zealand. (2000). Competencies for registration as an occupational therapist. Wellington, New Zealand: Author. Parsons, R. D., & Brown, K. S. (2002). Teacher as reflective practitioner and action researcher. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. Peloquin, S. M., & Abreu, B. C. (1996). The issue is. The academic and clinical worlds: shall we make meaningful connections? American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 50(7), 588-591. Polgar, S., & Thomas, S. A. (2000). Introduction to research in the health sciences. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Robinson, V., & Lai, M. K. (2006). Practitioner research for educators. A guide to improving classrooms and schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Roulston, K., Legette, R., Deloach, M., & Pitman, C. B. (2005). What is 'research' for teacher-researchers? Educational Action Research, 13(2), 169-190. Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books. Taylor, M. C. (2007). Evidence-based practice for occupational therapists. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing. Titchen, A., McGinley, M., & McCormack, B. (2004). Blending self-knowledge and professional knowledge in person-centred care. In J. Higgs, B. Richardson & M. A. Dahlgren (Eds.), Developing practice knowledge for health professionals (pp. 107-126). Edinburgh: Butterworh Heinemann. Valli, L. (1997). Listening to other voices: A description of teacher. PJE. Peabody Journal of Education, 72(1), 67. 14 Wlodarsky, R. L., & Walters, H. D. (2006). The reflective practitioner in higher education: The nature and characteristics of reflective practice among teacher education faculty [Electronic Version]. National Forum of Teacher Education Journal 16, 1-16. Retrieved 4 April 2008 from http://www.nationalforum.com/Electronic%20Journal%20Volumes/Wlodarsk y%20Rachel%20L%20The%20Reflectve%20Practitioner%20in%20Higher% 20Education.pdf. World Federation of Occupational Therapy. (2004). What is occupational therapy? Retrieved 5 April 2008, from http://wfot.org.au/information.asp Zeichner, K. M., & Noffke, S. E. (2001). Practitioner Research. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 298-330). Washington, DC: AERA. Zeichner, K. M., & Tabachnick, B. R. (2001). Reflections on reflective teaching. In J. Soler, A. Craft & H. Burgess (Eds.), Teacher Development. Exploring our own practice (pp. 72-87). London: Paul Chapman Publishing. Zimmerman, S. S., Bryam Hanson, D. J., Stube, J. E., Jedlicka, J. S., & Fox, L. (2007). Using the power of student reflection to enhance professional development [Electronic Version]. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 5, 1-7. Retrieved 20 March 2007 from http://ijahsp.nova.edu/articles/vol5num2/zimmerman.htm. 15