Privileges

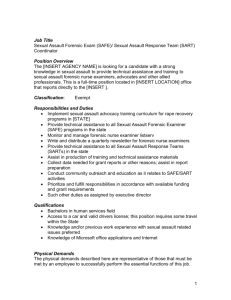

advertisement

The Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner: Should the Scope of the Physician-Patient Privilege Extend That Far? By Patricia A. Furci, M.A., R.N.1 I. Introduction For many years, sexual assault victims were routinely treated in busy, impersonal hospital emergency rooms, often waiting for several hours to be seen. These victims, thrust among the usual complement of accident and chest pain patients, were compelled not to eat, drink, or use the bathroom, since these activities could compromise physical evidence. Some victims walked out never to be examined; some stayed for the long, often police-accompanied physical examination. It was out of this troubled system that the idea for the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) program originated. The SANE program, a part of a national trend to systematically treat sexual assault victims2 at a neutral hospital setting, has been operating successfully throughout portions of the United States since 1976.3 However, almost 20 years passed before the nursing profession saw an increase in the number of SANE training and practice programs. In 1 The author is currently a 2L Day Student. At the time of this writing, the author was working with the New Jersey Legislature and the New Jersey State Attorney General's office in developing a floor amendment to New Jersey Assembly Bill No. 2083 proposing that a limited physician-patient privilege be extended to the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner. 2 Since most of the victims of sexual assault are female, the author in this writing will use the pronouns "she” and “her" when referring to victims of sexual assault. 3 See Linda Ledray and Susan Hohenhaus, Sexual Assault Clinical Issues: SANE Legislation and Lessons Learned, 22 J. OF EMERGENCY NURSING 460, 463-464 (1998). 1 the October, 1997, issue of Journal of Emergency Nursing,4 only 87 such programs were identified. Today, there are over 100 nationwide. 5 The SANE program, sometimes seen as part of the Sexual Assault Response Team (SART), uses specially trained registered professional nurses, often employees of the treating hospital, to perform prompt forensic examinations of rape and sexual assault victims once carried out by emergency room doctors. Furthermore, the SANE program introduces private, compassionate surroundings alongside the coordinated efforts of law enforcement and crisis intervention under the overall view of achieving a higher conviction rate. The Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (nurse examiner) generally completes the physical examination in two to three hours. The focus of this writing is these two to three hours where the nurse examines the sexual assault victim. During this time, the nurse examiner performs a forensic exam for evidentiary purposes. In order to collect forensic evidence, the nurse examiner must retrieve samples of tissue, hairs, and fluids from areas of the victim's body that were painfully violated during the assault. This exam, usually performed almost immediately after the episode of sexual violence, grinds at the very core of what is left of the victim's dignity, leaving nothing but the dust of utter vulnerability. However, it is also during this time that a relationship based on extraordinary trust and compassion is developed, whereby the sexual assault victim will speak with the nurse examiner, often offering additional unrelated information, believing it to be private and confidential. In actuality, the victim is imparting information that the nurse can later be compelled to disclose 4 See SANE Program Update (letter), 23 J. OF EMERGENCY NURSING 391, 396 (1997). See Debra Carr-Elsing, Crucial Caregivers; Nurse Examiners Specialize in Treating--and Testifying for--Sex Assault; Survivors, THE CAPITAL TIMES, December 4, 1997, at 1F. 5 2 during trial, or if documented, during discovery. In certain circumstances, the disclosure of this irrelevant information can be very damaging for the victim, as it may affect the integrity of her relationships, or worse, credibility itself. Should victims of sexual assault become aware of this lack of privilege in the nurse examiner-victim relationship, it may deter not only cooperation with the prosecution, but the actual reporting of sexual assaults as well. As a result, the ability to prosecute, and thereby to convict, will be lost. Although a rape-care advocate is available for counseling prior to and during the examination, it is the nurse examiner who spends the time providing the direct care while collecting evidence. This paper proposes the extension of the current physician-patient privilege to include the nurse examiner-victim relationship. Section II provides a general overview of the nationwide problem of sexual assault and of the SANE programs that treat victims of sexual assault nationwide. Sections III, IV, and V take an in-depth look at the law with regard to balancing the privacy interest of the victim of sexual assault with the countervailing rights of the defendant. Specifically, Section III addresses the fundamental need for the testimonial privilege in sexual assault cases. Section IV deals with scope of the limited physician-patient privilege in the context of the nurse examiner while explaining how other states have dealt with this issue. Section V examines the specific sexual assault evidentiary issues and the balancing of the countervailing rights of the defendant and how it has been applied in this situation. This writing concludes that it is imperative that the physician-patient privilege be extended to the sexual assault nurse examiner-victim relationship, at least on a limited basis. Additionally, an evidentiary framework of admissibility needs to be developed that would only 3 allow a defendant to use these irrelevant, yet potentially damaging disclosures, when there is a review conducted in camera. This burden of the in camera inspection, though heightened, needs to remain on the alleged assailant despite efforts to reflect the deliberate balancing of competing concerns. As a matter of public policy, the extension of a limited physician-patient privilege to the nurse examiner-victim relationship conducted with an in camera inspection is the only solution. II. Sexual Assault and the SANE Solution 1. The Problem of Sexual Assault Sexual assault is known as a crime of violence and hostility, and as is true with other violent crimes, it is difficult to get accurate estimates of the incidence of sexual assault. It is believed that sexual assault is a seriously underreported crime. Victims of rape and sexual assault may decide not to report the crime because they fear police attitudes and beliefs concerning rape as well as continuing to fear the perpetrator(s) of the rape.6 The legal term "rape" has been traditionally referred to as forced vaginal penetration of a woman by a male assailant. New Jersey, among other states, has abandoned this concept in favor of a gender-neutral concept of sexual assault.7 6 See ROBERT R. HAZELWOOD AND ANN W. BURGESS, PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF RAPE INVESTIGATION-A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH 13 (CRC Press, Inc., Second Edition 1995). 7 See, e.g., N.J. STAT. ANN. § 2A:61B-1 (West 2001). 4 According to the preliminary Uniform Crime Reporting Program 8 figures released by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, index crime decreased by 0.3 percent during the first 6 months of 2000 when compared to figures reported for the same time period of the previous year. In this report, violent and property crimes are combined to measure index crime where the crime index is composed of violent crimes such as murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault and property crimes of burglary, larceny-theft, motor-vehicle theft, and arson.9 Both violent crime and property crime declined by 0.3 percent when compared with the data from the same period in 1999. Decreases were recorded for the violent crimes of murder and robbery with robbery declining at 2.6 percent and murder declining at 1.8 percent.10 However, both rape and aggravated assault increased by 0.7 percent.11 The crime index fell in cities of populations over 250,000 and in cities of populations between 50,000 and 99,999, but in all other population groups and in suburban and rural counties the crime index increased.12 Although regionally, index crime dropped in the Northeast by 1.9 percent, in the West by 0.9 percent, and in the Midwest by 0.7 percent, it increased in the South, the most populous region, by 1.2 percent.13 As discussed in the Uniform Crime Report, there is "one forcible rape every six minutes."14 In addition to the abhorrent individual impact made by the sexual assault itself, there is also an extensive and dramatic societal impact as well. A sexual assault traumatizes both the victim 8 See Press Release, United States Department of Justice, Uniform Crime Report, Crime in the United States, 2000 (January, 2001) (This report is based on agencies submitting 3-6 months of data from January through June 2000.). 9 See Press Release, United States Department of Justice, supra note 8. 10 See id. 11 See id. 12 See id. 13 See id. 14 See id. 5 and her family/significant other(s) through its continued physical and emotional reactions long after the immediate danger has passed. Resumption of daily activities can vary from person to person while placing an enormous burden on the supportive family and significant others to help piece the victim’s life back together. Due to the nature of the crime, victims of sexual assault display unique crisis symptoms which respond best to early intervention.15 It is this early intervention with a crisis counselor or rape-care advocate that is critical in assisting in the sexual assault victim recovery process. Although some victims of sexual assault may recover quickly, there is another serious problem that, although primarily having its impact upon the victim, affects society at large due to its long-term impact on both the victim and her family. This is known as rape trauma syndrome (RTS). RTS is a general term used by psychologists to describe behavioral responses to rape. 16 RTS is a therapeutic and not a legal concept.17 It was first coined by two psychologists to describe a two-phase model of recovery exhibited by victims of rape. 18 Working at a Boston hospital, Ann Burgess and Lynda Holmstrom conducted a year-long study of the varied responses displayed by women seeking treatment for rape.19 Their study concluded that women characteristically exhibited a two-phase response to traumatic rape.20 15 See generally Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981, (1974). 16 See generally Toni M. Massaro, Experts, Psychology, Credibility, and Rape: The Rape Trauma Syndrome Issue and Its Implications for Expert Psychological Testimony, 69 MINN. L. REV. 395, 424 (1985). 17 See People v. Taylor, 75 N.Y.2d 277, 287 (1990). 18 See Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981 (1974). 19 See supra note 16. 20 See Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981, 982-83 (1974); see also People v. Taylor, 75 N.Y.2d 277, 283-86 (1990). 6 The first stage of recovery from the rape occurs during the immediate hours following the attack and consists of at least two different stress reactions.21 According to this model, approximately half of all women victimized exhibit an "expressive style" response, which is characterized by overtly emotional behavior.22 Victims in this group may experience a range of post-rape behavior that includes crying and feelings of anxiety.23 In contrast, others may exhibit a "controlled style" and may have none of these symptoms, which others may inadvertently interpret as evidence that no rape has occurred.24 The second phase of recovery, called the "long term reorganization" process was experienced by all victims in the Burgess/Holmstrom sample and is characterized by nightmares, phobic reactions, and sexual fears.25 This phase may last for several months and may render the victim and members of her family unable to handle daily activities of living. It is the total loss of control over even the entrails of one's own body that reinforces the feelings of utter vulnerability and powerlessness, thereby making control and power key psychological issues for all sexual assault victims. 26 At first, the recent sexual assault victim, especially when removed from the site of the attack, tends to be numb and withdrawn, talks slowly or inaudibly if at all, and denies or disbelieves the experience.27 Some victims, however, are visibly upset and highly emotional, sometimes palpably terrified.28 These two states may even alternate.29 Feelings of helplessness and extreme vulnerability (which may appear as indifference to one's fate) are endemic. 30 21 See Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981, 982 (1974). See id. at 982. 23 See id. 24 See id. 25 See supra note 21, at 983-84. 26 See id. at 982-84. 27 See id. 28 See id. 22 7 Once in the SANE program, the victim will be able to speak with a rape-care advocate prior to beginning any treatment, evidence collection or law enforcement interviews upon giving informed consent and expressing a clear desire to speak with the advocate. In most circumstances, absent of life threatening injuries, the sexual assault victim cannot be seen by the sexual assault nurse examiner without this informed consent. Today, in the absence of privilege, informed consent to see a sexual assault nurse examiner may be construed by a defense attorney as an open door to any and all information related by the sexual assault victim. Although it is not primarily addressed in this writing, it is questionable just how much the sexual assault victim in this fugue-like state following the sexual assault is actually able to comprehend. For this reason, certain courts have ruled that during this post-assault phase, the excited utterance exception to the hearsay rule should not apply. As stated by a Washington Court of Appeals, "…[H]er condition was a natural reaction to the recall of a traumatic event, one that could recur weeks and even years into the future. To permit the introduction of statements here would stretch the excited utterance exception [to the hearsay rule] beyond the premise of the rule."31 2. The SANE Solution SANE Programs developed in the United States in the late 1970's in Memphis and Tulsa (1976), Minneapolis (1977), and Amarillo (1978).32 In 1992, the Sexual Assault Response Team 29 See Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981, 982-84 (1974). See Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981, 982 (1974). 31 See State v. Patton, No. 39604-8-I, 1998 Wash. App. LEXIS 239, *7 (Wash. Ct. App. 1998). 32 See ROBERT R. HAZELWOOD AND ANN W. BURGESS, PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF RAPE INVESTIGATION-A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH 267 (CRC Press, Inc., Second Edition 1995). 30 8 (SART) of Minneapolis hosted the first national meeting bringing forensic nurses together. 33 The International Association of Forensic Nurses was established as an outgrowth of that meeting and is now responsible for the coordination of all research related to the crime of sexual assault.34 Today, nurse examiners are specially trained registered professional nurses who provide comprehensive care to sexual assault survivors.35 Certification for the nurse is usually attained through a local institution after completing a forty-hour training program and demonstrating competence in conducting a comprehensive evidential examination.36 Variations in the collection procedure and treatment components exist because hospitals and SANE programs each developed their own protocols.37 Although some variation is likely to continue, all forensic nursing examinations of sexual assault victims will include the following five essential components: 1) treatment and documentation of injuries; 2) treatment and evaluation of sexually transmitted diseases; 3) pregnancy risk evaluation and prevention; 4) crisis intervention and arrangements for follow-up counseling and; 5) collection of medicolegal evidence while maintaining the proper chain of evidence.38 The first New Jersey SANE programs began in 1997 in three separate counties. In 1998, the Attorney General appointed a thirty-seven member committee to develop standards to further provide services to sexual assault victims in response to the New Jersey Victims Rights Act, 33 See , e.g., ROBERT R. HAZELWOOD AND ANN W. BURGESS, PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF RAPE INVESTIGATION-A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH 267 (CRC Press, Inc., Second Edition 1995). 34 See id. at 267. 35 See id. 36 See id. at 266-67. 37 See id. 38 See id. 9 ensuring the rights of victims.39 In August 1998, the Attorney General’s office released a lengthy set of guidelines for prosecutors, law enforcement officials, and hospitals to follow in sexual assault cases. The fifty-eight page set of guidelines40 sought to encourage victims to report the crimes and to ensure that the victims felt they would be treated appropriately and with respect. Since that time, many SANE programs have been initiated in all twenty-one counties at hospital sites throughout New Jersey. There was a bill both in the New Jersey Assembly41 and in the Senate42 that was passed in March 2001 that changes the countywide SANE initiatives to a statewide sexual assault nurse examiner program (SSANE). Currently, it is pending signature by the Governor. The development of the overall SANE program is relatively recent in New Jersey and the standards of this program, while focusing on improving patient advocacy, are continuing to be refined. III. Fundamental Need for the Privilege Confidentiality and Privilege Confidentiality is a professional duty to refrain from revealing information about certain matters and is applied to the non-testimonial disclosure of confidential information,43 whereas privilege is a relief from the duty to speak in court proceedings. 44 Communications made in confidence are not protected purely because of their confidentiality, but may be kept secret only 39 See N.J. STAT. ANN. § 52:4B-44 (West 2000). See STANDARDS FOR PROVIDING SERVICES TO SURVIVORS OF SEXUAL ASSAULT, STATE OF NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF LAW AND PUBLIC SAFETY, DIVISION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE, AUGUST 1998. 41 See Statewide Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Program, A. 2083, 209th Leg. (N.J. 2001). 42 See Statewide Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Program, S. 190, 209th Leg. (N.J. 2000). 43 See generally Biddle v. Warren Gen. Hosp., 1998 Ohio App. LEXIS 1273, *8 (Ohio Ct. App. 1998). 44 See generally Biddle, 1998 LEXIS at *8; See also Perry v. Fiumano, 403 N.Y.S.2d 382, 385 (1978). 40 10 if premised upon a public policy expressed by statute or in furtherance of an overriding public concern of constitutional dimension.45 Although they are separate concepts, privilege and confidentiality are often confused. The "duty of confidentiality…protects patients from a significantly broader scope of disclosures that the physician-patient privilege."46 The presence of confidentiality alone is not enough to support a privilege.47 As stated by an Ohio court: The more intimate or embarrassing the information, the more damaging the disclosure will probably be. The [patient] may suffer ridicule, loss of business or professional reputation, or deterioration of personal relationships. Though injury often flows from widespread publication of disclosed information, the greatest injury may well be caused by disclosure to a single person, such as an employer or a spouse.48 Privilege is primarily a policy determination which is either embodied in a statute or arises from a constitutional provision that certain communications need to be protected from public inspection in order to encourage various aspects of the relationship in which the communication is made.49 For sexual assault victims there can be a misunderstanding between the concepts of confidentiality and privilege, with the real possibility of making this distinction only at trial. In the relationship between the sexual assault victim and the nurse examiner, there is a sense of extraordinary trust and confidence. The nurse examiners are registered professional nurses who are skilled in forensic nursing, but they are still considered caregivers. As nurse examiners 45 See Perry v. Fiumano, 403 N.Y.S.2d 382, 384 (1978) (citing People v. Doe, 403 N.Y.S.2d 375 (1978 ). See Biddle v. Warren Gen. Hosp., 1998 LEXIS 1273, *8 (Ohio Ct. App. 1998) (citing e.g., Dellenbach v. Robinson, 95 Ohio App.3d 358 (1993)). 47 See generally Perry v. Fiumano, 403 N.Y.S.2d 382 (1978). 48 See Biddle v. Warren Gen. Hosp., 1998 LEXIS 1273, *8-*9 (Ohio Ct. App. 1998) (citing Bullion v. Gadaleto, 872 F.Supp. 303, 306 (W.D.Va. 1995)). 46 11 become more forensically competent and focused on improving their evidence collection, the concern of many is that their newly acquired forensic role will overshadow their role as a nurse.50 As the role evolved throughout the United States in the late 1990s, and especially as nurse examiners became members of the sexual assault response teams (SARTs), the line between the nurse and the forensic evidence collector may have blurred.51 But this “blurring” is not usually apparent to the victim; the victim of a sexual assault still sees a caregiver, the nurse. When a victim of a sexual assault communicates with a nurse examiner during the physical exam, it is foreseeable that a victim may relate some intimacies to the nurse examiner. It is also foreseeable that among these confidential communications might be discussions of personal intimacies that are not relevant to the sexual assault. These communications may even be prefaced by the request not to disclose to her husband, her boyfriend, or even to another medical professional. For example, the victim may truly have the need at that time to discuss her recent abortion, her newly diagnosed cancer, or perhaps her newly diagnosed gonorrhea, in what she may perceive as a confidential setting. This need to talk may be may actually be an "expressive style" response to the sexual assault itself. Behavior such as this is seen in more than half of the women who had been sexually assaulted.52 Moreover, it is that maintenance of confidentiality under the umbrella of patient advocacy that is the essence of the SANE program. To breach that confidence would most certainly frustrate the purpose of the relationship and the SANE program. Should sexual assault 49 See generally Perry v. Fiumano, 403 N.Y.S.2d 382, 385 (1978) (citing 8 WIGMORE, EVIDENCE [MCNAUGHTON § 2285, p. 527). 50 See Linda Ledray, SANE: Advocate, Forensic Technician, Nurse? 27 J. OF EMERGENCY NURSING 90, 91 (February 2001). 51 See id. at 92. 52 See Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981, 982 (1974). REV.], 12 victims realize that their confidential statements are not protected under privilege future assaults may go unreported, even with the most victim-centered support system as the SANE program, as no victim wants to open the door to testimony about all her private affairs. Few medical situations that present to the health professional are as emotionally charged as rape.53 Yet, the terrible anguish of the rape victim, while not always so visible, is ravaging and pervasive, as it permeates so many threads of the victim's life. 54 As the nurse examiner performs this lengthy and elaborate examination on the sexual assault victim in a room within a hospital emergency department, she is also performing a form of crisis intervention, as this encounter with the nurse examiner is often the victim’s first interaction with society after the crime.55 While it is important that the examination be thorough, it must also be sensitive.56 This overall examination includes history, physical examination, and collection of specimens for laboratory analysis.57 In addition to the physical exam and collection of specimens, the nurse examiner conducts interviews with the victim to obtain the victim's general medical history, the victim's sexual history, a history of the incident and postincident events.58 In order to collect evidence, the nurse examiner must retrieve samples of tissue, hairs, and fluids from areas of the victim's body, both inside and outside, that were violated during the assault. Specimens collected routinely include any clothing that is torn, bloody, or soiled in the course of the assault, any foreign debris such as hair fibers or dried secretions adhering to the 53 See SHARON M. CROWLEY, SEXUAL ASSAULT- THE MEDICAL-LEGAL EXAMINATION 12 (Appleton and Lange, 1999). 54 See id. at 12. 55 See generally ROBERT R. HAZELWOOD AND ANN W. BURGESS, PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF RAPE INVESTIGATION-A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH 255-61 (CRC Press, Inc., Second Edition 1995). 56 See generally id at 255-61. 57 See generally id. 58 See generally id. 13 victim's body, and fingernail scrapings.59 Treatment for the prevention of pregnancy as well as venereal disease is also provided to the victim.60 In performing this lengthy examination, the nurse examiner is orally communicating with the victim during each step of the process. Also during this time, there is communication by the victim to the nurse examiner. Should the case be brought to trial, the nurse examiner will be compelled to testify as to the observation of physical injuries and other related conditions or statements made by the victim. However, the victim may relate to the nurse examiner certain facts that are unrelated or irrelevant to the assault but may sometimes become part of the medical record or attested to under oath by the nurse examiner. Moreover, in some cases, it is the nurse examiner who exercises discretion as to what is being entered into the medical record of the victim. It is the content of these confidential, unrelated communications that may become damaging to the victim or to the integrity of her current marriage or familial relationships should they be revealed. For example, should the nurse examiner observe an older episiotomy61 scar on the perineum of the victim, the victim may disclose that she had a child out of wedlock that is unknown to her current spouse or significant other. Under the present law, a defense attorney would be able to interrogate the nurse examiner about this scar on the perineum since it may appear in the diagram and/or narrative portion of the medical record as part of the nurse examiner's observations. Even if the victim were told that the information would be kept 59 See ROBERT R. HAZELWOOD AND ANN W. BURGESS, PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF RAPE INVESTIGATION-A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH 259 (CRC Press, Inc., Second Edition 1995). 60 See id at 259. 14 confidential, the nurse examiner would be compelled to testify as to the statement made by the victim regarding the reason for the scar identified in the medical record. This fact of this scar is irrelevant to the assault and does not implicate any legitimate law enforcement needs. In the interest of privacy, some human relationships are fundamental to human dignity and should be free from state interference.62 Since privacy is an emerging right, a discussion of privacy often may become a listing of examples where the right has been recognized instead of a simple definition. Although we live in a world of noisy self-confession, privacy allows us to keep certain facts to ourselves if we so choose.63 An example of privacy is included in testimonial privileges, such as confidentiality of disclosures during physician-patient, attorneyclient, and psychotherapist-patient relationship. Determining the scope of privilege is difficult because it involves the weighing of two competing interests: privacy interests of the victim and the interests of the state. When there are changes to the social attitudes of citizens in a state, each state is free to create and define the scope of privilege for certain relationships to reflect just this change. 64 As society's views on privacy rights and its understanding of sexual assault issues evolve, the scope of privilege granted to the sexual assault victim-nurse examiner relationship needs to be expanded forthwith before harms arise. In New Jersey today, should sexual assault victims realize that their communications with the nurse examiner have no protection, they may either forego treatment altogether or be less candid in their communications. Worse, they might never 61 See TABER'S CYCLOPEDIC MEDICAL DICTIONARY E-51 (12th ed. 1974). (An episiotomy scar is reflective of a surgical incision made at the time of childbirth to avoid laceration of the mother's perineum and to facilitate the delivery of a baby). 62 See generally Kerry L. Morse, A Uniform Testimonial Privilege for Mental Health Professionals, 51 OHIO ST. L.J. 741, 742-44 (1990). 63 See ELLEN ALDERMAN & CAROLINE KENNEDY, THE RIGHT TO PRIVACY xiii (Vintage Books 1997). 15 seek treatment or return prosecutors' calls once they have been seen by the nurse examiner. Without the sexual assault victim's involvement, few convictions will ever be obtained. IV. The Limited Victim- Nurse Examiner Privilege 1. Scope of Physician-Patient Privileges It is in the area of defining the scope of the protection that the privilege affords to communications between medical or health professionals where state laws have shown the most variety and the greatest inequities. For example, in New Jersey, [c]onfidential communications between physician and patient means such information transmitted between physician and patient including information obtained by an examination of the patient, as is transmitted in confidence and by a means which, so far as the patient is aware, discloses the information to no third persons other than those reasonably necessary for the transmission of the information or the accomplishment of the purpose for which it is transmitted. 65 The New Jersey statute,66 enacted in 1968, recognizes a limited privilege for information obtained by physicians during the course of treating their patients. 67 While its scope is considerably narrower than the privilege which protects communications between psychologists and their patients,68 there is no privilege extended to the nurse-patient relationship.69 The rule 64 See FED. R. EVID. 501. N.J. STAT. ANN. § 2A:84A-22.1(D) (WEST 2000). 66 N.J. STAT. ANN. § 2A:84A-22.1(D) (WEST 2000). 67 See E. JUDSON JENNINGS & GLEN WEISSENBERGER, NEW JERSEY EVIDENCE: 2000 COURTROOM MANUAL 159 (1999). 68 See id. 69 N.J. STAT. ANN. § 2A:84A-22.1(D) (WEST 2000). 65 16 and the decisions70 construing the statute, in recognizing the strong tradition in the medical profession favoring confidentiality in the diagnosis and treatment of injury, oftentimes is inconsistent with the need to evaluate patients while determining a claim for damages or the guilt or innocence of a defendant.71 The physician-patient privilege may be invoked by a patient to bar her own testimony, testimony from the physician, or testimony from a third person who obtained the information in violation of the privilege.72 Since the privilege is limited, it may be overcome by other statutes which require physicians to report information concerning communicable disease, injury by gunshot, abuse, or neglect, and the like. 73 Should the physician-patient privilege in New Jersey continues to remain as construed so as not to extend to the nurse examiner, at least on a limited basis, then it is foreseeable that the reporting of sexual assaults will decline as victims realize their interests and confidentiality issues are not protected. In New York, the scope of the privilege that exists between health professionals, including nurses and their patients, is absolute. For example as stated in State v. Keating.74 There is a limited number of privileges. They are absolute in the sense that even in matters involving public justice, a court may not compel disclosure of confidential communications between husband and wife, between attorney and client, between physician, dentists, nurses and their patients, and between clergymen and communicants.75 70 See State v. Schreiber, 122 N.J. 579 (1991); See also Behringer v. Princeton Medical Ctr., 249 N.J. Super. 597 (N.J. Super. Ct. Law Div.)1991. 71 See E. JUDSON JENNINGS & GLEN WEISSENBERGER, NEW JERSEY EVIDENCE: 2000 COURTROOM MANUAL 159 (1999). 72 See id. 73 N.J. STAT. ANN. § 2A:84A-22.5 (WEST 2000). 74 See State v. Keating, 141 N.Y.S.2d 562 (N.Y. App. Div. 1955). 75 See State v. Keating, 141 N.Y.S.2d 562, 565 (N.Y. App. Div. 1955) (citing Civ. Prac Act §§ 349-354; People v. Shapiro, 308 N.Y. 453 (1954). 17 In contrast with New Jersey, New York76 has an absolute privilege extended to those relationships between registered professional nurses and licensed practical nurses and their patients. Indiana has recognized a limited privilege extended to the registered nurse and the advanced practice nurse, but the scope does not reach to the licensed practical nurse. 77 Another distinction is that the nurse-patient privilege recognized by statute in Oregon is absolute, but it does not extend to the licensed practical nurse.78 Moreover, there are other jurisdictions where if the statutes do not expressly include nurses within the testimonial privilege of physician, then it has been held that the privilege will not be extended to nurses. Some of these states 79 include Arizona, California, Colorado, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin. With all of these various differences and features of statutory and judicially created testimonial privileges, there is clearly a conflict on the question whether the statutes merely extend the privilege to physicians and include nurses by implication.80 In many cases the privilege was denied, since the courts took the view that the statutes, being in derogation of common law, should be strictly construed and limited to those persons specifically named, whereas, in other cases, the privilege was recognized with the courts taking the view that the privilege extended to the physician would be ineffective if the nurse is permitted to testify. 81 76 See N.Y. C.P.L.R. 4504 (2000 Consol.). See Darnell v. State, 1996 Ind. App. LEXIS 1604, ***4-***5 (Ind. Ct. App. 1996). 78 See OR. REV. STAT. § 40.240 (1999); See, e.g., Deere v. Epstein, 307 Or. 348, 354 (1989). 79 See, e.g., W. R. Habeeb, Annotation, Evidence: Privilege of Communications By or To Nurse or Attendant, 47 A.L.R.2D 742, *3 (1999). 77 18 2. Limited Privileges and the Sexual Assault Victim There are important interests that support the need for a privilege to exist between the sexual assault victim and the nurse examiner. Statutes and common law define privileged relationships in an attempt "to protect citizens' private and personal confidences from unwarranted public scrutiny."82 The courts and/or the legislatures need to determine the proper scope of the privilege granted to the nurse examiner as it applies to sexual assault victims. Under a conditional or limited privilege, victims of sexual assault have the right to prevent disclosure of any confidential communications, but the courts could overrule the privilege if there is a sufficiently strong countervailing interest. This is a worthy solution because it represents a compromise between the privacy interest of the sexual assault victim and the defendant's right to confrontation and compulsory process. The limited physician-patient privilege extended to the victim-nurse examiner relationship would allow the prosecutor the ability to prosecute certain "victimless" crimes that occur in obvious situations of abuse where the abused victim is in denial, or is in fear and endures the abuse as a part of an unhealthy, and often fatal, lifestyle. As seen currently in Massachusetts,83 a limited privilege with an in camera inspection is preferable to a limited privilege in which the defense attorney can obtain direct access to the victim's records. However, the defendant should bear the burden of establishing relevance in order to obtain any in camera inspections; the limited privilege with an in camera inspection cannot be construed as a 'fishing expedition' for the defense. 80 See, e.g., Habeeb, 47 A.L.R.2D at *1 See, e.g., id. at *1 82 See Ellen M. Crowley, In Camera Inspections of Privileged Records in Sexual Assault Trials, 21 AM. J. L. & MED. 131, 131 (1995). 83 See Commonwealth v. Neumyer, 432 Mass. 23 (2000); see also Commonwealth v. Zane Z., 2001 Mass. App. Ct. Lexis 194 (March 9, 2001). 81 19 The use of a limited privilege with an in camera inspection would support the nurse examiner-victim relationship aligning with government's compelling interest in assisting the victim in the recovery process, which would outweigh even the defendant's right to confrontation.84 In Pennsylvania v. Ritchie,85 the Court balanced a state statutory privilege and a defendant's constitutional right of due process.86 Charged with rape, defendant Ritchie sought access to investigatory files regarding his daughter, the complainant. 87 On appeal, the Supreme Court remanded the case and ordered the trial judge to conduct an in camera review of all potentially exculpatory evidence to determine its materiality, rather than allow defense counsel direct access to the material.88 In Massachusetts, the development and implementation of the current in camera balancing test, as outlined in Commonwealth v. Bishop89 and modified in Commonwealth v. Fuller,90 have endeavored to protect the physician-patient relationship without impeding a defendant's constitutionally protected right.91 Prior to these holdings, a Massachusetts court92 held that since the credibility of a victim is a fundamental issue in a sexual assault case, all privileged records must be made available to counsel without any prior showing by the defendant of special circumstances demonstrating a particularized need for access to the communications.93 The court's vague guidelines afforded trial judges broad discretion in allowing the defense access 84 See Commonwealth v. Wilson, 429 Pa. Super. 197 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1992); See Pennsylvania v. Ritchie, 480 U.S. 39 (1987). 86 See Commonwealth v. Two Juveniles, 397 Mass. 261, 265-67 (1986); 87 See id. at 263. 88 See id. 89 See Commonwealth v. Bishop, 416 Mass. 169 (Mass. 1993). 90 See Fuller, 423 Mass. 216, 223 (1996). 91 See id. 92 See Commonwealth v. Figueroa, 413 Mass. 193 (1992). 93 See 413 Mass. at 202. 85 20 to a victim's statutorily protected privileged records.94 The Bishop court introduced a five-stage test emphasizing consistent in camera inspections.95 Each stage of the test focused on the relevancy of the records and their relation to the case.96 The stages built upon one another and each stage contingent upon determinations made in the prior stage(s).97 The stages included: privilege determination; relevancy determination; access to relevant materials; disclosure at trial and; the trial.98 The Bishop case applied the five-stage test to a conditional privilege but left the lower courts to question whether the new rule applied to absolutely privileged records. 99 Additionally, under the Bishop test, stage two was found to be too vague and overly broad for trial courts, since theories regarding relevancy became a general inquiry using boiler-plate language.100 In Commonwealth v. Fuller,101 the court modified the over-reaching effect noted in stage two. Fuller held that the procedural five stage test applied to any type of asserted privilege.102 Now whenever a defendant seeks to encroach upon a victim's statutorily protected privilege he must follow the standard outlined in Bishop and modified in Fuller.103 In a recent opinion, Commonwealth v. Zane Z.104 the court reaffirmed the application of the Bishop105 test as 94 See Bishop, 416 Mass. 169. See Bishop, 416 Mass. at 179-81. 96 See id. 97 See id. 98 See id. 99 See id. at 174. 100 See Fuller, 423 Mass. at 223-24; See also Bishop, 416 Mass. at 180-81. 101 See Commonwealth v. Fuller, 423 Mass. 216 (1996). 102 See id. at 224. 103 See Commonwealth v. Oliveira, 431 Mass. 609, 616-17 (2000). 104 See Commonwealth v. Zane Z., 2001 Mass. App. Ct. Lexis 194 (March 9, 2001). 105 See Bishop, 416 Mass. at 180-81. 95 21 modified under Fuller,106 and clarified under the other recent opinions of Oliveira107 and Neumyer108. Trial courts, however, in reviewing caselaw should not deem records relevant simply because they arose from the incident of sexual assault. To do so would most certainly subject many privileged communications to in camera inspections on request, which will directly abrogate the very privileges designed to encourage victim participation and reporting of the crimes. The practice of reviewing victim's communications in camera will aid both the litigants and the practitioners such as nurse examiners in clearly defining the parameters and procedure for discovery of potentially exculpatory evidence. This balancing test, a conditional or limited privilege with an in camera requirement, recognizes the constitutional rights of a defendant and protects against the random disclosure of a victim's confidential communications. V. Collateral Evidentiary Issues in Sexual Assault Cases 1. Relevance and the Countervailing Rights of the Defendant When a criminal defendant seeks to introduce relevant evidence barred by a testimonial privilege, a conflict arises between the defendant's interest in introducing exculpatory evidence and the government's interest in promoting social policy; it is well established that a defendant has no constitutional right to present irrelevant evidence,109 however, even marginally relevant evidence, though otherwise unobjectionable, may nevertheless be excluded if its probative value 106 See Fuller, 423 Mass. 216. See Commonwealth v. Oliveira, 431 Mass. 609, 616-17 (2000). 108 See generally Commonwealth v. Neumyer, 432 Mass. 23 (2000). 109 See Wood v. Alaska, 957 F.2d 1544, 1549 (9th Cir. 1992). 107 22 is substantially outweighed by principles of adversarial fairness and legitimate social policy. While the Sixth Amendment extends protection only to logically relevant evidence, the rights of the accused in a sexual assault crime can be constitutionally limited by the "valid legislative determination that rape victims deserve heightened protection."110 Since the late 1960’s, Supreme Court decisions based on the compulsory process clause,111 the confrontation clause,112 and the due process clause113 have held that in some situations the defendant's right to present relevant evidence must override evidentiary rules to the contrary. Most of these cases involved situations in which the exclusionary evidence rule was designed to enhance accurate fact-finding114 rather than to promote a social policy. In Davis v. Alaska,115 however, the Supreme Court held that a statutorily created evidentiary privilege could not be applied to prevent the introduction of evidence that tended to show bias on the part of the chief government witness. Further, in Pennsylvania v. Ritchie,116 the Court held that a statutorily created privilege could not be applied to bar the defendant from discovering all evidence protected by the privilege.117 Moreover, the Court has indicated that a defendant would also have a constitutional right to discover or introduce evidence protected by a privilege in other situations.118 110 See Michigan v. Lucas, 500 U.S. 145, 151 (1991). See Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967). See also Rock v. Arkansas, 483 U.S. 44 (1987). 112 See Davis v. Alaska, 415 U.S. 308 (1974). 113 See Chambers v. Mississippi, 410 U.S. 284 (1973. See also Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95 (1979). 114 Chambers and Green both involved applications of the hearsay rule which was designed to exclude evidence that is unreliable or may be given too much weight by the jury. See Chambers, 410 U.S. at 295; see Green, 442 U.S. at 97. Washington and Rock involved evidentiary rules that were designed to exclude categories of evidence considered untrustworthy. See Washington, 388 U.S. at 19; see Rock, 483 U.S. at 47. 115 See Davis v. Alaska, 415 U.S. 308 (1974). 116 See Pennsylvania v. Ritchie, 480 U.S. 39 (1987). 117 See Ritchie, 480 U.S. at 52. 118 See generally Rovario v. United States, 353 U.S. 53 (1957). 111 23 Embodied within the standard of relevancy are issues of admissibility, especially in the realm of sexual assault and evidentiary privilege. Assuming that the evidentiary privilege is reasonably calculated to promote a legitimate social policy, the interests in conflict--the defendant's interest in presenting relevant evidence at a criminal trial and society's interest in advancing a social policy--can be so contrasting that a court may have difficulty determining which should prevail. The physician-patient privilege extension to the sexual assault nurse examiner-victim relationship is analogous to the enactment of the rape shield statutes. These rape shield statutes, enacted in most jurisdictions, establish an evidentiary privilege by providing that, when a defendant is on trial for rape, the defendant may not ordinarily introduce the alleged victim's prior sexual conduct into evidence.119 Quite frequently, defendants charged with rape claim that they have a constitutional right to introduce evidence protected by the privilege. A court might first determine whether the privilege at issue has the purpose of assisting the government in performing one of its essential functions. Much like the objective of the rape shield statutes, the extension of the physician-patient privilege to the sexual assault nurse examiner-victim relationship would further encourage the victim to report the assault and assist in bringing the offender to justice by testifying against him in court. In addition, the privilege would enhance accurate fact-finding by excluding evidence of marginal relevance that may distract or prejudice the jury. Encouraging rape victims to report rapes services the government's compelling interest to prosecute suspected rapists. 119 The exclusionary rules enacted by the rape shield statutes are intended to promote social policies in that they are intended to protect the victim's sexual privacy and to assist law enforcement. Moreover, they are also designed to promote accurate fact-finding because the victim's prior sexual conduct is of marginal relevance and the introduction if thus evidence may divert the jury from considering the issue at hand. 24 In the area of crimes involving sexual assault, courts must have a rule that provides relatively clear guidelines. Thus, utilizing the guiding principles developed in this writing, a defendant's constitutional right to introduce evidence protected by an evidentiary privilege should be interpreted to include the right to introduce evidence material to his defense. Taken in context, the alleged victim's prior sexual conduct (as protected by the rape shield statutes), as well as conduct and communications unrelated to the sexual assault (as revealed to the nurse examiner) may tend to establish bias because it provides the defense with an open door to areas of the victim's life unrelated to the sexual assault at hand. In this context, as in Davis v. Alaska,120 evidence tending to establish bias on the part of a critical government witness is very likely to have an impact on the result. Should the defendant be able to meet the basic standard of materiality, introduction of the evidence actually protected by the rape-shield statute or the proposed evidentiary privilege might be permitted. This does not mean, of course, that defendants would generally be permitted to discover or introduce evidence protected by a rape shield statute. The defendant in a sexual assault case would not be permitted to discover or introduce instances of the victim's prior sexual conduct simply for the purpose of impeaching her credibility. Even if a judge were to adhere to the view that a victim's lack of virtue relates to her honesty, a finding that such evidence would be material in the sense that it would be reasonably likely to affect the outcome would be clearly erroneous. It can be argued that defeating a privilege only when the defendant seeks to introduce material exculpatory evidence would not harm individuals who make confidential 120 See Davis v. Alaska, 415 U.S. 308, 317-18 (1974). 25 communications. In the realm of sexual assault, it can be argued that the victim's communication with the nurse examiner would be disclosed only at the defendant's trial and measures might be taken to insure that it is not later used to adversely affect the legal or other interests of the victim. Nevertheless, confidential communications, such as those protected by the physician-patient privilege, are privileged to protect the privacy of the communication as it relates to the diagnosis and treatment of the patient. Since privileges are often justified on the assumption that they are needed to encourage confidential communications, it can be postulated that the victim's knowledge that her communications would in some situations be admissible in court at trial would sometimes deter her from making the communication. Thus, when a privilege is designed to provide maximum protection for the victim, even admitting material evidence protected by the privilege only on behalf of criminal defendants may have the overall chilling effect of reducing the protection afforded to the victim. If it will often deter such communications, then, even though the value of admitting the privileged evidence in a particular case may far outweigh the harm to the person protected by the privilege, the harm of admitting the evidence may clearly outweigh the benefit because the admission may substantially diminish the extent to which any such communications will be made in the future. Thus, even if the value of protecting the sexual assault victim is viewed as paramount, the extent to which that value may be advanced by the admission of privileged evidence in a particular case may be outweighed by the harm to some other value that occurs as a result of the disclosure of the protected evidence. 26 In two United States Supreme Court cases, Roviaro v. United States121 and Davis122 contain language that suggests that a defendant's right to introduce evidence protected by a privilege depends on a balancing of interests. Drawing upon one or both of these cases, some courts123 have suggested that the admissibility of evidence protected by a privilege should be determined by a balancing test under which the importance of the evidence offered by the defendant should be weighed against the interests to be served by the privilege. The balancing approach allows for consideration of all relevant factors relating to the privilege in question, not just those factors that relate to whether the privilege, either in general or in the context of its specific application, may be properly characterized as one that favors the government. This is important in some situations as the introduction of evidence protected by a privilege might defeat a particular witness or victim's expectation of privacy. Rather than focusing on one particular aspect of the problem, it is more appropriate to devise principles that seek to take into account the full range of interests involved. The principles developed in this writing can be used by courts to determine whether a defendant in a sexual assault crime has a constitutional right to discover or introduce evidence protected by an extension of the physician-patient privilege in the nurse examiner-victim relationship. A court could accept the basic principles presented in this writing and still draw on alternative principles for dealing with specific situations that create special problems. Thus, a court might take into account the fact that application of a privilege in a particular situation does not seem to promote any strong societal interest. Similarly, a court could reject the principle that 121 See Rovario v. United States, 353 U.S. 53, 62 (1957). See Davis v. Alaska, 415 U.S. 308, 319 (1974). 123 See, e.g., United States v. Smith, 780 U.S. 1102, 1107-10 (4th Cir. 1985). 122 27 a defendant has a constitutional right to introduce material evidence whether or not it is protected by a privilege and still hold in a particular case that the defendant must be afforded a constitutional right to introduce vital defense evidence that is privileged. The proposed principles are not intended to preclude the exclusion of these factors but to provide a framework of analysis that will generally be useful in determining the scope of a defendant's constitutional right to discover or introduce evidence protected by this extended privilege. That the disclosure of irrelevant issues such as children borne out of wedlock prior to the sexual assault, or perhaps the diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease would undoubtedly engender anguish and embarrassment is indisputable. Equally clear is Supreme Court precedent suggesting that the limited interest in minimizing embarrassment, standing alone, may not in itself outweigh the accused's interest in presenting relevant evidence.124 In Davis,125 the Court held that the state's interest in keeping a juvenile record private did not outweigh the defendant's interest in producing relevant evidence.126 The Supreme Court has consistently recognized that the more critical the excluded evidence to the defense of the accused, the more important must be the asserted state interest. 127 Perhaps most troubling is the possible inclusion of confidential communications that arise in the context of the physical exam performed by the sexual assault nurse examiner. Probing clinical interviews, whether used as evidentiary collection or not, represent a profound intrusion into the privacy of the victim and strike at the heart of both the rape shield statutes core values as 124 See generally Davis, 415 U.S. 308. See 415 U.S. 308. 126 See 415 U.S. at 319. 127 See Stephens v. Miller, 13 F.3d 998, 1020 (7th Cir. 1994) (citing Chambers v. Mississippi, 410 U.S. 284, 293303 (1973)). 125 28 well as the integrity of societal relationships between individuals. These conversations occur at a time when the woman is most vulnerable and in one of the most compromising positions she will see in her lifetime. The resurrection of these confidential conversations in a courtroom, having occurred between the nurse examiner and the victim over several long hours during which an invasive physical exam was performed, conjures legitimate fears of intrusive questioning and deeply felt exposure. Enough exposure, if publicly revealed, to deter the next victim from seeking treatment for the next rape. When juries are faced with counterintuitive behaviors of the victim such as a controlled reaction following a rape128 or individually chosen life experiences such as abortion, juries can be misled down the path of acquittal. Pervasive rape myths and sexual assault misconceptions can result in situations where juries discredit the victim and refuse to punish the alleged rapist. By disallowing irrelevant confidential communications that occurred between the nurse examiner and the victim that would otherwise foster this scheme, prosecution experts can debunk myths about rape and its victims. This function provides a valuable opportunity to challenge prejudicial views while equalizing the odds for conviction. So long as the state refrains from presenting particularized testimony involving irrelevant matters, the constitutional rights of the accused are adequately honored and the victim's privacy is preserved.129 2. The Hearsay Exception for Medical Diagnoses and Treatment 128 See generally Ann W. Burgess & Lynda L. Holstrom, Rape Trauma Syndrome, 131 AM. J. PSYCHIATRY 981 (1974). 129 See People v. Wheeler, 602 Ill.2d 298, 309-13 (1992). 29 The legal basis for the admissibility of statements made by a victim to a physician, nurse or other allied health personnel is found in the medical diagnosis and treatment exception to the hearsay rule.130 The Federal Rule of Evidence defines hearsay as: "….[a] statement other than one made by the declarant while testifying at the trial or hearing, offered in evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted."131 The Federal Rule of Evidence 803(4)132 and the New Jersey Rule133 provide for the admission of "[s]tatements made for purposes of medical diagnosis or treatment and describing medical history, or past or present symptoms, pain, or sensations, or the inception or general character of the cause or external source thereof insofar as reasonably pertinent to diagnosis or treatment."134 The rationale is that the declarant has a strong motive to speak truthfully and accurately because her successful treatment depends upon it.135 This strong self-interest makes FRE 803(4) a 'firmly rooted' hearsay exception.136 The ‘firmly rooted' exceptions satisfy the reliability standards of the Confrontation Clause because 'adversarial testing would add little to their reliability.'137 In the case United States v. Iron Shell,138 the court created a two-part test for admission of statements under rule 803(4), where the Court recognized two rationales underlying the medical diagnosis and treatment exception under the hearsay rule and joined them into a single test for admissibility. As stated in Iron Shell, "[f]irst, is the declarant's motive consistent with the 130 See ROBERT R. HAZELWOOD AND ANN W. BURGESS, PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF RAPE INVESTIGATION-A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH 267 (CRC Press, Inc., Second Edition 1995). 131 See id. at 25, (citing FED. R. EVID. 802(b)). 132 See FED. R. EVID. 803(4). 133 See N.J. R. EVID. 803(C)(4). 134 See FED. R. EVID. 803(4). 135 See United States v. Renville, 779 F.2d 430, 436 (8th Cir. 1985). 136 See White v. Illinois, 502 U.S. 346, 355 (1992). 137 See Idaho v. Wright, 497 U.S. 805, 815-16, 821 (1990). 138 See United States v. Iron Shell, 633 F.2d 77 (8th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 450 U.S. 1001 (1981). 30 purpose of the rule; and second, is it reasonable for the physician to rely on the information in diagnosis or treatment." 139 States vary in their test of this medical diagnosis and treatment exception to the hearsay rule. As stated by a Pennsylvania Supreme Court: Most federal and state courts subject statements proffered under Exception (4) [of F.R.E. 803 or its state counterpart] to a two-part reliability test. First, the declarant must have a motive consistent with obtaining medical care. Second, the content of the statement must be such as is reasonably relied upon by medical personnel for treatment or diagnosis.140 As seen in a very recent case in Ohio,141 the Court re-evaluated the medical diagnosis and treatment hearsay exception when it ruled in a child abuse case. The Court stated, "[t]he first inquiry is whether Nurse…was involved in the diagnosis and/or treatment of a medical condition and was not serving as an evidence collector or making case for the prosecution…[t]he next inquiry is whether there was an indicia of trustworthiness associated with the …statements."142 Although the statements were found admissible under the medical diagnosis and treatment exception to the hearsay rule, it was clear the case distinguished that evidence collection was not involved in the diagnosis and/or treatment of a medical condition. Although the term 'evidence collection' was not defined, Crozier concluded that since the physical examination was performed specifically as a "checkup," statements made during that exam fell within the medical diagnosis hearsay exception. 139 See United States v. Iron Shell, 633 F.2d 77, 84 (8th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 450 U.S. 1001 (1981). See Commonwealth v. Smith, 545 Pa. 487, 493 (1996). 141 See State v. Crozier, 2001 Ohio Ct. App. LEXIS 693 (February 21, 2001) 142 See State v. Crozier, 2001 Ohio Ct. App. LEXIS 693, *4-*5 (February 21, 2001) (describing child victim's statements to a nurse following a rape). 140 31 In a recent New Hampshire Supreme Court domestic abuse case, the Court applied the Roberts' test and stated that "[T]here are three areas of inquiry for a court applying Rule 803(4): the declarant's intent; the subject matter of the statements; and whether there are circumstances indicating trustworthiness of the statements."143 The Court explained where "one can infer that a person who voluntarily visits a doctor intends to obtain medical attention"144 but that "the statements must describe medical history, symptoms, pain, sensations, or their cause or source to an extent reasonably pertinent to diagnosis or treatment."145 It can be argued that a sexual assault victim's statements that may address a prior abortion, a child out of wedlock, or even perhaps a recent extra-marital affair resulting in the transmission of disease are not reasonably pertinent to medical diagnosis and treatment of the sexual assault. In some cases,146 it was clear that as long as the statements were made to the Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner during the evidentiary exam, they became admissible under the medical diagnosis and treatment exception to hearsay. Therefore, it can be concluded that these statements made to the nurse examiner as part of a history and physical examination following the incident, therefore become extremely important from a trial advocacy perspective because statements regarding the cause of injuries, including specific details of the assault and the 143 See State v. Soldi, 2000 N.H. LEXIS 119, *10 (December 28, 2000 ) (citing State v. Roberts, 136 N.H. 731, 740 (1993)) (describing physician testimony in domestic abuse case as being admissible under medical diagnosis exception to hearsay rule). 144 See Soldi, 2000 N.H. at *11 (citing Roberts at 741). 145 See Soldi, 2000 N.H. at *11 (citing Roberts at 741) 146 See Tkacik v. State, Nos. 07-98-0391CR and 07-98-0392-CR, 1999 Tex. App. LEXIS 6288 (August 23, 1999) (citing that testimony of rape victim's statements from a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner was admissible because they were pertinent to medical diagnoses). See also Fletcher v. State, 1999 Tex. LEXIS 7930 (Tex. App. October 21, 1999) (Nurse's testimony based on statements made during course of examination were admissible under medical-statements exception). See also Beheler v. State, 1999 Tex. LEXIS 6993 (Tex. App. May 17, 2000) (citing statements made by a child to a nurse fell within hearsay exception because they were made for medical diagnosis and treatment). 32 identity of the offender, could be introduced through the nurse examiner. 147 However, the Federal Rules of Evidence are clear regarding statements made for purposes of investigation in civil or criminal litigation.148 Statements made to medical and nursing personnel cannot be admitted under this exception.149 Although this issue has not been tested in New Jersey, there are other states 150 where this exception to the hearsay rule has been used in the context of the nurse examiner. In Tkacik v. Texas,151 the appellant argued that hearsay portions of testimony of a registered nurse employed as a nurse examiner were inadmissible because she provided no treatment for the child as the injured party. He argued that the function of the nurse examiner was to gather evidence to be used in prosecuting sexual assault cases, not to provide a diagnosis or treatment since none was provided.152 The state argued the nurse examiner obtained a history from the child so that she could diagnose and treat, and then performed a physical exam.153 As stated in Tkacik, "[a] diagnosis included the opinion derived from a physical examination."154 The Court went on to say that the nurse examiner expressed several opinions as the result of her examination and the condition of the child's body.155 The state continued to say that if a nurse performs the dual role of collecting evidence and providing medical service by securing statements from the victim at 147 See ROBERT R. HAZELWOOD AND ANN W. BURGESS, PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF RAPE INVESTIGATION-A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH 25 (CRC Press, Inc., Second Edition 1995). 148 See id. 149 See id. 150 This author noted that many cases involving a nurse examiner are regarded as unpublished opinions, thereby having no precedential value. 151 See Tkacik v. State, Nos. 07-98-0391-CR and 07-98-0392-CR, 1999 Tex. App. LEXIS 5345 (August 23, 1999). 152 Id. at *3. 153 Id. at *3. 154 Id. at *3-*4 (citing WEBSTER'S II NEW RIVERSIDE UNIVERSITY DICTIONARY 372 (1984)). 155 Id. at *4. 33 the time she made an examination, the report and testimony fit within the meaning of the rule. 156 In another case, the court found that the "…medical diagnoses and treatment exception to the hearsay rule is based on the assumption that the patient appreciates that the effectiveness of the treatment may depend on the accuracy of the information provided to the physician."157 Currently, some courts choose to not follow either criteria and instead base their rulings merely on the testimony of health professionals.158 These rulings are unpredictable because they depend on whether the doctor states he or she relies upon such statements to provide a medical diagnosis or treatment for the victim. Therefore, there will be a divergence in the application of the medical diagnosis and treatment exception to hearsay as there are various opinions and testimony from health professionals. To that end, the incongruous and expansive applications of the medical diagnosis and treatment exception makes Rule 803(4) a less reliable hearsay exception because it is gradually losing its once defined boundaries. It is this reasoning along with the inconsistent applications of the medical diagnosis and treatment exception to the hearsay rule in sexual assault cases that unconditionally reinforces the need for a limited privilege extension with an in camera inspection to be afforded to the sexual assault victim-nurse examiner relationship. Although there is limited caselaw in the areas involving the sexual assault nurse examiner, similar issues of confidentiality and use of medical diagnosis and treatment exception to the hearsay rule are seen most frequently in the areas of sexual abuse of children. This situation can 156 See Tkacik v. State at *3. See Fleming v. State, 1991 Tex. LEXIS 2717, *28 (Tex. Ct. App. 1991) (citing See EDWARD CLEARY, MCCORMICK ON EVIDENCE §292 (3d ed. 1984). 158 See generally Fletcher v. State, 1999 Tex. LEXIS 7930 (Tex. App. October 21, 1999). 157 34 be further complicated when the nurse examiner is providing the health care, not the physician. When there is alleged sexual abuse of children, some courts permit registered nurses to diagnosis human responses to health problems; however, most prohibit them from providing a medical diagnosis.159 A New Jersey statute160 recognized a firm distinction between nursing diagnosis and medical diagnosis. It was held that a nursing diagnosis identifies signs and symptoms only to the extent necessary to carry out the nursing regimen rather than making final conclusions about the identity and cause of the underlying disease.161 Diagnosing in the context of nursing practice means that an initial nursing assessment is performed and through analysis of the data collected, the nurse can develop an appropriate nursing plan of care. This is done to implement that plan along with methods to evaluate the patient and to re-assess the patient. Such diagnostic processes are distinct from a medical diagnosis. If the legislature does not provide the limited privilege to the sexual assault nurse examiner, the medical diagnosis and treatment exception to hearsay will continuously be misconstrued and ultimately be weakened. The medical diagnosis and treatment exception was never intended to include damaging irrelevant statements made by the victim of a sexual assault. VI. Conclusion This writing discussed the extension of the physician-patient privilege to the sexual assault nurse examiner-victim relationship, at least on a limited basis, with an in camera inspection. If this is not accomplished, defendants will continue to assert the right to proffer 159 See State v. One Marlin Rifle, 319 N.J. Super. 359 (App. Div. 1999). See N.J. STAT. ANN. § 45:11-23-52 (West 2000) (citing the New Jersey Nurse Practice Act). 161 See Flanagan v. Labe, 547 Pa. 254, 256 (Pa. 1997). 160 35 negative evidence concerning their victim, to cross-examine victims concerning their sexual history through the hearsay exception to medical diagnosis and treatment, and to compel knowledge of possibly damaging, irrelevant communications that occurred between the victim and the nurse examiner during the evidentiary examination. Without it, the actions applied by courts will continue to misconstrue the principles of the medical diagnosis and treatment exception to hearsay allowing such statements into evidence. In effect, the divergent and broad court rulings of the medical diagnosis and treatment exception make this exception less reliable. The courts must carefully evaluate the public policy issues balancing legitimately protected privacy interests of sexual assault victims against Sixth Amendment rights of the accused. However, an evidentiary framework of admissibility needs to be developed that would only allow a defendant to use these irrelevant, yet potentially damaging disclosures made by the victim during the forensic exam when there is a review conducted in camera. This burden of requiring an in camera inspection, though heightened, needs to remain on the alleged assailant despite efforts to consciously reflect the deliberate balancing of competing concerns. With the limited physician-patient privilege extended to include the nurse examiner, there would be no fear that a later disclosure of information would arise as to thwart the judicial process in obtaining testimony and eventual conviction. There would be no harm to the victim and more likely than not, the reporting of this egregious crime would rise. With improved reporting of sexual assault in any context, the conviction rate should rise proportionately. 36 37