рассказы

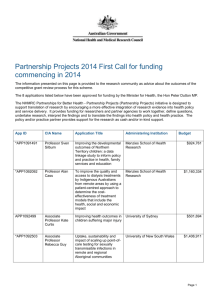

advertisement