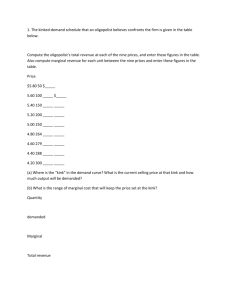

27 – Oligopoly and Strategic Behavior

advertisement

Chapter 27 Oligopoly and Strategic Behavior Overview In this chapter the oligopoly model is presented and its major characteristics are discussed. The reason why oligopoly occurs is discussed, and the concept of the concentration ratio is introduced. Strategic behavior under oligopolistic conditions along with game theory is presented. The model of price leadership as a form of strategic behavior with implicit collusion is developed. The ways oligopolists deter entry by potential competitors is analyzed. The nature and significance of network effects is then examined. Finally, the various market structures are compared. Outline I. Oligopoly: An oligopoly is a market structure in which there are very few sellers. Each seller knows the other sellers will react to its changes in prices and quantities. An oligopoly market structure can exist for either a homogeneous or a differentiated product. A. Characteristics of Oligopoly 1. Small Number of Firms: An oligopoly exists when the few top firms account for an overwhelming percentage of total industry output. 2. Interdependence: This is also called strategic dependence, which is a situation in which one firm’s actions with respect to output, price, quality, advertising, and related changes may be strategically countered by one or more other firms in the industry. Such dependence can only exist when there are a few major firms in an industry. B. Why Oligopoly Occurs 1. Economies of Scale: The strongest reason that has been offered for the existence of oligopoly is economies of scale. Economies of scale are defined as a production situation in which a doubling of output results in less that a doubling of total costs. The firm’s average total cost curve will slope downward as it produces more and more output. Average total cost can be reduced by continuing to expand the scale of operation. 2. Barriers to Entry: These barriers include legal barriers, such as patents, and control and ownership over critical supplies. 3. Oligopoly by Merger: A merger is the joining of two of more firms under a single ownership or control. There are two types of mergers. A horizontal merger involves firms producing or selling a similar product. A vertical merger occurs when one firm merges with another from which it purchases an input or to which it sells an output. C. Measuring Industry Concentration 1. Concentration Ratio: The percentage of all sales contributed by the leading four or leading eight firms in an industry: sometimes called the industry concentration ratio. (See Table 27—1.) 2. U.S. Concentration Ratios: The concept of an industry is necessarily arbitrary. As a consequence, concentration ratios rise as we narrow the definition of an industry and fall as we broaden it. (See Table 27—2.) D. Oligopoly, Efficiency, and Resource Allocation: Some oligopolists charge prices that are greater than marginal cost. There is no definite evidence of serious resource allocation in the United States. The more U.S. firms face competition from the rest of the world, the less any oligopoly will be able to exercise market power. III. Strategic Behavior and Game Theory: When there are relatively few firms in an industry, each reacts to the price, quantity, quality, and new product innovations that the others undertake. Each oligopolist has a reaction function which is the manner in which one oligopolist reacts to a change in price (or output or quality) of another oligopolist. Game theory is the analytical framework in which two or more individuals, companies, or nations compete for certain payoffs that depend on the strategy that the others employ. The plans made by these individuals are known as game strategies. A. Some Basic Notions About Game Theory: Games can be cooperative or non-cooperative. They are classified by whether the payoffs are negative, zero, or positive. A cooperative game is one in which players explicitly collude to make themselves better off. With firms, it involves companies colluding in order to make higher than competitive rates of return. A non-cooperative game is a game in which players neither collude nor negotiate in any way. Applied to firms, it is a situation in which there are few firms and each firm has some ability to change price. A zero sum game is a game in which one player’s losses are exactly offset by the other player’s gains. A negative-sum game is a game in which both players are worse off at the end of the game. A positive-sum game is a game in which both players are better off at the end of the game. 1. Strategies in Noncooperative Games: A strategy is any rule that is used to make a choice, e.g., always pick heads. The goal is to devise a dominant strategy. A dominant strategy will yield the highest benefit for the player using it. These strategies are generally successful no matter what actions other players take. B. Applying Game Theory to Pricing Strategies: An example of the use of game theory is presented. (See Figure 27—2.) C. Opportunistic Behavior: Actions that ignore possible long-run benefits of cooperation and focus solely on short-run gains. This kind of behavior can be contrasted to tit-for-tat strategic behavior when repeat transactions are likely. Here a player will behave well as long as others do likewise. 1 IV. Price Rigidity and the Kinked Demand Curve: Assume that rivals will match all price decreases (in order not to be undersold) but not price increases (because they want to capture more business). There is no collusion. The implications of this reaction function are rigid prices and a kinked demand curve. A. Nature of the Kinked Demand Curve: An oligopoly firm will assume that if it lowers price, rivals will react by matching that reduction to avoid losing their respective shares of the market. The oligopolist lowering the price will not greatly increase its quantity demanded and total revenues will fall. If it increases price, rivals will not follow. Thus, a higher price will cause quantity demanded to decease rapidly and total revenues will fall. There is a kink in the demand curve. The resulting marginal revenue curve has a discontinuous portion. (See Figure 27—3.) B. Price Rigidity: The kinked demand curve analysis may help explain why price changes might be infrequent in an oligopolistic industry without collusion. Each oligopolist can only expect lower revenues if it changes price. (See Figure 27—3.) 1. A Break in the Marginal Revenue Curve: A theoretical reason for price inflexibility under the kinked demand curve model has to do with the discontinuous portion of the marginal revenue curve. As long as the marginal cost curve passes through the discontinuity, the firm will not change price. (See Figure 27—4.) 2. A Theory of Price Rigidity: As long as the marginal cost curve is in the discontinuous portion of the firm’s marginal revenue curve neither price nor quantity will change since the price and quantity are at the profit maximizing level. (See Figure 27—4.) C. Criticisms of the Kinked Demand Curve: If every oligopolistic firm faced a kinked demand curve, it would not pay to change prices. The problem is that the kinked demand curve does not show us how supply and demand originally determined the going price of an oligopolist’s product. Oligopoly prices do not appear to be as rigid, particularly in the upward direction, as the kinked demand curve theory implies. V. Strategic Behavior with Implicit Collusion: A Model of Price Leadership: Price leadership is a model of a pricing practice in many oligopolistic industries and is a form of tacit collusion. A. The Theory of Price Leadership: The largest firm publishes its price list ahead of its competitors, who then follow those prices. This is also called parallel pricing. By definition, price leadership requires one firm to be the leader. Because of laws against collusion, firms in an industry cannot communicate who the price leader will be directly. That is why the largest firm often becomes the price leader. B. Price Wars: Price leadership may not always work. If the price leader ends up much better off than those firms that follow, they may not set prices according to the dominant firm. A price war may result. A price war is a pricing campaign designed to capture additional market share by repeatedly cutting prices. VI. Deterring Entry into an Industry: An important part of game playing has to do with how potential competitors might react to a decision. Existing firms in an industry devise strategies to deter entrance into that industry. By getting a local, state, or federal government to restrict entry, or by adopting certain pricing and investment strategies they may deter the entrance of new firms. A. Increasing Entry Costs: Any strategy undertaken by firms in an industry with the intent or effect of raising the cost of entry into the industry by a new firm. To sustain a long price war, existing firms might invest in excess capacity so that they may expand output during the price war, thus signaling potential competitors that they will engage in a price war. Existing domestic firms can also raise the cost of entry by foreign firms by getting the U.S. government to pass stringent environmental or health and safety standards. B. Limit-Pricing Strategies: The existing firms may lower their market price until they sell the same quantity as before a new firm entered the industry. Existing firms limit their price to be above competitive prices, but if there is a new entrant, the new limit price will be below the one at which a new firm can make a profit. The limit-pricing model is a model that hypothesizes a group of colluding sellers who together set the highest common price they believe they can charge without new firms seeking to enter the industry. C. Raising Customers’ Switching Costs: If an existing firm can make it more costly for customers to switch from its product or service to a competitor’s, the existing firm can deter entry. In the computer industry switching costs were high because computer operating systems were not compatible across computer operating systems. VII. Network Effects: This is a situation in which a consumer’s willingness to purchase a good or service is influenced by how many others also buy the item. A. Network Effects and Market Feedback 2 1. Positive Market Feedback: A tendency for a good or service to come into favor with additional consumers because other consumers have chosen to buy the item. 2. Negative Market Feedback: A tendency for a good or service to fall out of favor with more consumers because other consumers have stopped purchasing the item. B. Network Effects and Industry Concentration: In some industries a few firms can reap the benefits of positive market feedback. These firms can then capture the bulk of the sales in the market. VIII. Comparing Market Structures: Market structures are compared in Table 27—3. 3