Nebraska Center for Writers

advertisement

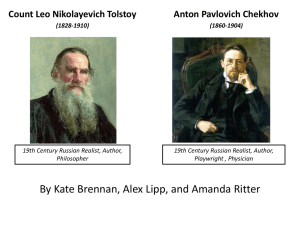

Nebraska Center for Writers What the Critics Say About Anton Chekhov The following passages focus mainly on Chekhov's fiction. Reading Anton Chekhov's stories, one feels oneself in a melancholy day of late autumn, when the air is transparent and the outline of naked trees, narrow houses, greyish people, is sharp. Everything is strange, lonely, motionless, helpless. The horizon, blue and empty, melts into the pale sky, and its breath is terribly cold upon the earth, which is covered with frozen mud. The author's mind, like autumn sun, shows up in hard outline the monotonous roads, the crooked streets, the little squalid houses in which tiny, miserable people are stifled by boredom and laziness and fill the houses with an unintelligible, drowsy bustle. ... There passes before one a long file of men and women, slaves of their love, of their stupidity and idleness, of their greed for the good things of life; there walk the slaves of the dark fear of life; they straggle anxiously along, filling life with incoherent words about the future, feeling that in the present there is no place for them. ... In front of that dreary, gray crowd of helpless people there passed a great, wise, and observant man: he looked at all these dreary inhabitants of his country, and, with a sad smile, with a tone of gentle but deep reproach, with anguish in his face and in his heart, in a beautiful and sincere voice, he said to them: "You live badly, my friends. It is shameful to live like that." — Maxim Gorky, Reminiscences of Anton Chekhov (BW Huebsch, 1921) His genius lies above all in his creative gifts as a writer of short stories. ... In fact, his plays derive directly from his stories, in which, it seems to me, the texture is far richer. — VS Pritchett a master of understatement, of concealed meaning, of twilight scenes and of prose as compressed as poetry, whose heroes don't want what they want? — Andrei Voznesensky The Chekhov mood is that cave in which are kept all the unseen and hardly palpable treasures of Chekhov's soul, so often beyond the reach of mere consciousness. — Constantin Stanislavski, My Life in Art (Theatre Arts Books, 1924) When I had read this story ["Ward No 6"], I was filled with awe. I could not remain in my room and went out of doors. I felt as if I were locked up in a ward too. — Nikolai Lenin Tolstoy is reported to have said that Tchekov was a photographer, a very talented photographer, it is true, but still only a photographer. But Tchekov has one quality which is difficult to find among photographers, and that is humour. His stories are frequently deliciously droll. They are also often full of pathos, and they invariably possess the peculiarly Russian quality of simplicity and unaffectedness. He never underlines his effects, he never nudges the reader's elbow. — Maurice Baring, Landmarks in Russian Literature (Methuen, 1916) Tchekov was the poet of hopelessness. Stubbornly, sadly, monotonously, during all the years of his literary activity, nearly a quarter of a century long, Tchekov was doing one thing alone: by one means or another he was killing human hopes. Herein, I hold, lies the essence of his creation. — Lev Shestov, Anton Tchekov and Other Essays (Maunsel & Co, 1916) His stories raise over and over again that oldest of questions about realism. For Tchehov, as Mrs [Constance] Garnett and many others have remarked, belongs most obviously to the Maupassant school of "unflinching realists." But that after all does not take us very far, and we may and do legitimately ask about the realist what he is attempting to do with this unflinching realism. The answer is easy in the case of the old photographic and cinematographic realist. Carefully and accurately to convey a piece of bleak and naked life into the covers of a book was to him enough: that was the object of his art and Art. ... But if Tchehov is an unflinching realist, his object is most certainly not unflinching realism. It is true that many of his shortest short stories seem at first sight to be the work of a man who has delicately fastidiously, and ironically picked up with the extreme tips of his fingers a little piece of real life, and then with minute care and skill pinned it by means of words into a book. — Leonard Woolf, "Miscellany: Tchehov," New Statesman, IX, 227, August 11, 1917 Chekhov is essentially a humorist. His is not the quiet, genial humor of an Addison or a Washington Irving nor the more subtle, often boisterous humor of a Mark Twain. His is rather the cynical chuckle of a grown-up watching a child assume grimaces of deep earnestness and selfimportance. In his earlier stories the laughable, and it is a more or less cheerful laugh, with little of the serious behind it, often predominates. But as the stories grow more in volume, the undercurrent of gloom and a stifled groan of pain become more and more audible, until, in the later volumes, his laugh quite eloquently suggest the ominous combination of submission to Fate and Mephistophelian despair. — N Bryllion Fagin, "Anton Chekhov: The Master of the Gray Short-Story," Poet Lore, XXXII, Autumn 1921 How did he do it? Not by dispensing with plot, but by using a totally different kind of plot, the tissues of which, as in life, lie below the surface of events, and, unobtrusive, shape our destiny. Thus he all but overlooks the eventplot; more, he deliberately lets it be as casual as it is in real life. ... To Chehov literature is life made intelligible by the discovery of form — the form that is invisible in life but which is seen when, mentally, you step aside to get a better view of life. Life, because it has aspects innumerable, seems blurred and devoid of all form. And since literature must have form, and life has none, realists of the past thought that they could not paint life in the aggregate and preserve form, and thus saw fit to express one aspect of life at a time. Until a wholly new aspect occurred to Chehov — that of life in the aggregate: which aspect, in truth, is his form. — William Gerhardi, Anton Chehov: A Critical Study (Duffield & Co, 1923) Our first impressions of Tchekov are not of simplicity but of bewilderment. What is the point of it, and why does he make a story out of this? we ask as we read story after story. A man falls in love with a married woman, and they part and meet, and in the end are left talking about their position and by what means they can be free from "this intolerable bondage." "‘How? How?' he asked, clutching his head. ... And it seemed as though in a little while the solution would be found and then a new and splendid life would begin." That is the end. A postman drives a student to the station and all the way the student tries to make the postman talk, but he remains silent. Suddenly the postman says unexpectedly, "It's against the regulations to take any one with the post." And he walks up and down the platform with a look of anger on his face. "With whom was he angry? Was it with people, with poverty, with the autumn nights?" Again, that story ends. But is it the end, we ask? We have rather the feeling that we have overrun our signals; or it is as if a tune had stopped short without the expected chords to close it. These stories are inconclusive, we say, and proceed to frame a criticism based upon the assumption that stories ought to conclude in a way that we recognise. In so doing we raise the question of our own fitness as readers. Where the tune is familiar and the end emphatic — lovers united, villains discomfited, intrigues exposed — as it is in most Victorian fiction, we can scarcely go wrong, but where the tune is unfamiliar and the end a note of interrogation or merely the information that they went on talking, as it is in Tchekov, we need a very daring and alert sense of literature to make us hear the tune, and in particular those last notes which complete the harmony. — Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1925) For he is a poet of atmosphere, of the vague thing they called in Russian nastroenie and in German Stimmung, but for which there is no adequate word in English, except this meteorological metaphor. — DS Mirsky, Modern Russian Literature (Oxford UP, 1925) Now, of Tchehov I would say that his stories have apparently neither head nor tail, they seem to be all middle like a tortoise. Many who have tried to imitate him however have failed to realise that the heads and tails are only tucked in. ... I should say that Tchehov has been the most potent magnet to young writers in several countries for the last twenty years. He was a very great writer, but his influence has been almost wholly dissolvent. For he worked naturally in a method which seems easy, but which is very hard for Westerners, and his works became accessible to Western Europe at a time when writers were restless, and eager to make good without hard labour ... — John Galsworthy, Selected Essays and Addresses (Heinemann, 1932) But when we read a story like "My Life" we are bound to notice that by the end of the tale none of the characters has changed. They spend their time going round in circles. The same can be said of "The Darling" or "The Lady with the Dog." There is essential change in neither character nor situation. ... One feels they are caught not in the toils of a story but in the wayward meshes of a mood. The things which occur to the two chief characters [in "My Life"] are like the wind soughing in the branches of two trees in winter. The branches bend and sway; they toss and struggle; but once the wind has died away they come to rest and form once more their familiar pattern against the sky. Life is something which passes through them like a sigh; it does not grow out of them. — VS Pritchett, "Books in General: ‘My Life,'" New Statesman, XXV, 631, March 27, 1943 Chekhov raised the portrayal of banality to the level of world literature. He developed the short story as a form of literary art to one of its highest peaks, and the translation of his stories into English has constituted one of the greatest single literary influences at work in the short story of America, England, and Ireland. This influence has been one of the factors encouraging the short-story writers of these nations to revolt against the conventional plot story and seek in simple and realistic terms to make of the story a form that more seriously reflects life. — James T Farrell, The League of Frightened Philistines and Other Papers (Vanguard, 1952) If we follow his line of development, we see that, beginning with satirical jokes, Chekhov goes on to master the art of the ironic anecdote, so often pathetic or tragic (it would hardly, one would think, be possible to complain of a good many of these that one did not understand the point); these, in turn, begin to expand into something more rounded-out (the dense but concise study of character and situation) and eventually — in what Mr Hingley calls Chekhov's Tolstoyan period ("A Nervous Breakdown," for example) — take on a new moral interest or attain, as in his "clinical" one ("The Black Monk"), a new psychological depth. These studies become more comprehensive — "The Steppe," "A Dreary Story," "Ward No 6" — in such a way as to cover a whole life en raccourci or an experience in fuller detail. Such pieces are not short stories but what Henry James called nouvelles. — Edmund Wilson, A Window on Russia (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1952) Chekhov belonged to the age which followed the heroic generation of Tolstoi and Dostoevski. At times his characters live, or think that they live, in the world of his predecessors. One is tempted to say that they all seem to have read Tolstoi and Dostoevski and are trying to be Tolstoi and Dostoevski characters. But Chekhov has lost the passion of his predessors because he has lost the faith which sustains it. He and often his characters are skeptics rather than believers. The soul searchings of his personages are not terrible but, frequently, ridiculous, and it is their futility rather than their tragedy which most impresses him. Whereas Tolstoi and Dostoevski were prophets, he is a critic and a satirist. They believed; he doubts. They saw tragedy; he sees, at most, pathos, usually tinged with absurdity. — Joseph Wood Krutch, Modern Drama: A Definition and an Estimate (Cornell UP, 1953) I know enough about the business of storytelling to be able to put my finger on certain devices that maintain the astonishing freshness of [Chekhov's] stories. The devices are not unlike those that [Toulouse Lautrec] and Degas used; ultimately, they can all be traced to the naturalistic theory about describing what you see — the simplest artistic theory in the world until you begin to ask yourself what you do see. As in Degas' "L'Absinthe" the figures are not placed solidly in the center of the picture and the figure of the man trails off inexplicably behind the frame, so in Chekhov there is always a deliberate artlessness of composition — people walk on and off, and sometimes a fascinating character is described and then dropped. Men are always being caught buttoning their trousers and women pulling up their stockings, and their outraged glances as we catch them at it are always part of the total ironic effect. — Frank O'Connor, "A Writer Who Refused to Pretend," New York Times Book Review, January 17, 1960 If one really wants to understand Chekhov, one must realize that he was the moralist of the venial sin, the man who laid it down that a soul is damned not for murder, adultery or embezzlement but for the small, unrecognized sins of ill-temper, untruthfulness, stinginess and disloyalty. ... As in Degas and Lautrec the whole beautiful theory of the art schools is blown sky-high, so in Chekhov the whole nineteenth-century conception of morals is blown sky-high. This is not morality as anyone from Jane Austen or Trollope would have recognized it, though I suspect that an orthodox theologian might have something very interesting to say about it. ... Sin to him is ultimately a lack of refinement, the inability to get through a badly cooked meal without a scene. — Frank O'Connor, "A Writer Who Refused to Pretend," New York Times Book Review, January 17, 1960 What becomes of the traditional division of a story — prologue, exposition or development and finally dénouement or conclusion — in Chekhov's work? The ‘prologue' or introduction to the story is generally reduced to nil, or to a short sentence that immediately goes to the heart of the matter. ... The Chekhov of the final years ended his stories and plays abruptly, on a sort of musical chord. There is, strictly speaking, no longer an ending at all. ... The same form of ending is to be found in nearly all his works after 1894. — Sophie Laffitte, Chekhov, 1860-1904 (Angus & Robertson, 1973) His meticulous anatomies of complicated human impulse and response, his view of what's funny and poignant, his clear-eyed observance of life as lived — all somehow matches our experience. — Richard Ford The most obvious feature of love as portrayed by Chekhov is that it almost never works out to the satisfaction of either party. ... He seems to have regarded young love as an illusion, but an illusion so beautiful that he repeatedly used it for the evocation of atmosphere. His young men in love are liable to meet with one of three different fates, none of them enviable. Either their love is not returned, or they are separated from their beloved by circumstances, or, finally, they get married and the illusion ends in inevitable disillusion. All these experiences involve emotions and memories which, however frustrating to the participants, make ideal material for the construction of atmosphere. — Ronald Hingley, Chekhov: A Biographical and Critical Study (George Allen & Unwin, 1966) The situation, indeed the entire plot of "The Lady with the Dog," is obvious, even banal, and its merit as a work of art lies in the artistry with which Chekhov has preserved in the story a balance between the poetic and the prosaic, and in the careful characterization, dependent upon the use of half-tones. — Virginia Llewellyn Smith, Anton Chekhov and "The Lady with the Dog" (Oxford UP, 1973) Among the most pervasive elements in the writing of Chekhov is irony, especially the irony of unfulfillment. ... One form this irony takes is the realization that achievement, arriving at one's goal, seldom brings satisfaction. ... Irony is also experienced in the failure to realize hopes, in the pursuit of what proves to be a will-o'-the-wisp, and in lack of awareness of what the present offers. — Ruth Davies, The Great Books of Russia (U of Oklahoma P, 1973) Chekhov's irony is not the self-satisfied amusement of an author pulling his characters along on strings through a labyrinth; it is not the cynical resignation to fate of Greek tragedy; it is not just a manner that hints at gold reserves of knowledge to back the paper currency of talk. Chekhov's irony is much more modern, much closer to Samuel Beckett than to the great tradition of the European novel. What he knows and what his characters often ignore is that "les choses sont contre nous" ["things are against us"]. His characters' statements not only get them nowhere, they are not even possible to complete, so insistent is the absurd importunacy of sand in the speaker's boots, the compulsion to fiddle with a sleeve, the banging of an iron rail outside the house. Not only the plays but also the stories are full of extraneous noises, physical tics and silences which give an ironic impotence to the sanest rationalisations. — Donald Rayfield, Chekhov: The Evolution of His art What happens in the course of the Chekhov play is that the characters are shown responding and reacting to one another on the emotional level: Chekhov creates among them what may be called an emotional network, in which it is not the interplay of character but the interplay of emotion that holds the attention of the audience. ... A kind of electric field exists among all the persons in a Chekhovian group. ... Emotional preoccupations in the Chekhov play do not remain private and submerged, but are brought to the surface as the characters intermingle and become emotionally involved with one another. This as it were activates the emotional network, and emotions may come to vibrate between particular individuals. ... It is on occasions such as these, when the emotional network is vibrating with an unusually high degree of harmony or disharmony, that the characters' emotional preoccupations are likely to be most clearly revealed. — Harvey Pitcher, The Chekhov Play: A New Interpretation (Chatto & Windus, 1973) Anton Chekhov's late stories mark a pivotal moment in European fiction — the point where nineteenth-century realist conventions of the short story begin their transformation into the modern form. The Russian master, therefore, straddles two traditions. On one side is the anti-Romantic realism of Maupassant with its sharp observation of external social detail and human behavior conveyed within a tightly drawn plot. On the other side is the modern psychological realism of early Joyce in which the action is mostly internal and expressed in an associative narrative built on epiphanic moments. Taking elements from both sides, Chekhov forged a powerful individual style that prefigures modernism without losing most of the traditional trappings of the form. If Maupassant excelled at creating credible narrative surprise, Chekhov had a genius for conveying the astonishing possibilities of human nature. His psychological insight was profound and dynamic. Joyce may have more exactly captured the texture of human consciousness, but no short story writer has better expressed its often invisible complexities. — Dana Gioia, Eclectic Literary Review (Fall/Winter 1998)