Top of Form Second Industrial Revolution The Second Industrial

Second Industrial Revolution

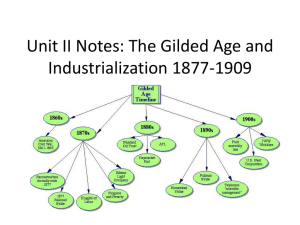

The Second Industrial Revolution , beginning roughly in the early 1870s and lasting through World War II, continued the processes of mechanization, urbanization, and change that had begun during the first phase of the Industrial Revolution. The

Second Industrial Revolution produced products for consumers based on new scientific and technological advances that would have been unimaginable only 20 years before, most notably automobiles, airplanes, home appliances, movies, radios, and televisions. The rise of massive corporate entities capable of wielding enormous amounts of power also marked the Second

Industrial Revolution, as did the fruition of the labor movement and other social movements intent on alleviating the ills of urbanization.

America had made amazing progress during the first phase of the Industrial Revolution. Industries formed to produce the machines needed to settle the new country, growing to enormous sizes when they were successful, but they still required a lot of skilled labor to produce goods. Companies operating during the Second Industrial Revolution created production and assembly processes that could be executed with less skill and fewer workers. Whereas the first phase of Industrial Revolution had been dominated by men like Francis Lowell, Samuel Colt, and Cyrus McCormick, all of whom were manufacturers, the Second Industrial Revolution was led by such a diverse array of people as banker J.P. Morgan, inventor Thomas Edison, financier John D. Rockefeller, steel producer

Andrew Carnegie, and manufacturer Henry Ford.

Morgan contributed to the Second Industrial Revolution by using his financial and organizational skills to turn successful companies into industry giants. Through his commercial bank J.P. Morgan and Company, he financed promising new technologies and invested in such emerging industries as railroads, electrical equipment, and steel production. The bank not only financed the growth of many of the great American industries but also strengthened them through consolidations and mergers. Occasionally, it even underwrote governments during financial crises and wars, including the U.S. government twice (once in 1894 and then again in 1907).

Morgan's bank was the most influential financial institution for much of the Second Industrial Revolution, particularly before the founding of the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913. In fact, with no national bank to encourage industrialization until 1913, Morgan may be said to have financed much of America's industrial growth during this period single-handedly.

In his first consolidation attempt, Morgan assembled many of the regional railroads that had been weakened in the financial Panic of 1873 into five large railroads that were formidable competitors in their markets. Although the large railroads reduced competition, under Morgan's guidance they brought stability to the transportation industry, which also helped stabilize the emerging industrial corporations. After his success with the railroads, Morgan concentrated next on companies producing electrical equipment and steel, following generally that same pattern he had with transportation. This crucial triumvirate of industries served as the foundation for the industrial innovations enacted by a wide variety of manufacturers during this period and substantially aided in the spread of technology.

The undisputed leader in the area of inventions during this period, Edison contributed to the Second Industrial Revolution with his invention of the light bulb and the electric power generation and distribution equipment to light it. This technology created the electrical equipment industry and provided the electric power to operate America's industries. In 1878, Edison formed the Edison

Electric Light Company to build electric power plants and to produce such electrical components as light bulbs, generators, transformers, and switches.

Although Edison worked mostly on solutions for the home, he also provided industry with a better way to power their machines using electricity rather than steam-driven belts. Electrically powered machines could be run directly from electricity supplied by

Edison's electric power plants. Electrifying the machines was a significant improvement because each machine then contained its own built-in power, an electric motor connected to the machine's electrical source, rather than being dependent on a single steam engine that powered several machines. Now machines could be relocated or upgraded by just plugging them into an electrical outlet, making them more flexible and safer without the overhead belts.

In addition, the electric power station did not have to be near the factory, so companies often bought power from independent power plants that also provided electricity to homes and other businesses. Separating the power station from the manufacturing plant allowed owners to size their factories to fit their business needs and to locate them anywhere electricity was available, which resulted in decentralizing many businesses and spreading work throughout the country.

As Edison's company grew, it needed much more funding and better management and turned to J.P. Morgan and Company for help. In 1892, Morgan bought the Edison Electric Light Company and the Thompson-Houston Company, another electrical equipment manufacturer, and merged them into the General Electric Company (GE), to build equipment for generating and using electricity.

Although General Electric never attained a monopoly in the electrical industry, it did create a new form of company, now called a technology company, that could rapidly introduce products from new technologies and then control its markets. In addition to equipment to generate and distribute electrical power, it produces almost everything relating to electricity, including appliances, entertainment equipment, medical equipment, locomotives, and even jet engines. Today, it is one of the largest companies in the world.

Supplying another key component of the Second Industrial Revolution, Carnegie founded the Carnegie Steel Company to provide the steel for America's buildings, bridges, industrial equipment, steel ships, and automobiles. He also led the conversion of

America's iron industry to a steel industry and in the process, created the largest steel company in the world.

In 1875, Carnegie's company built a state-of-the-art steel plant in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania using blast furnaces to reduce iron ore to pig iron, Bessemer furnaces to reduce pig iron to steel ingots, and rolling mills to fabricate ingots into blooms and slabs for later fabrication to finished shapes. It also used an early version of an open-hearth furnace to produce steel alloys for specialized applications. The plant was highly successful, due mainly to Carnegie's gamble on the Bessemer furnace. Production volumes were enormous, the quality of the steel was good, and costs were the lowest in the industry.

Railroads immediately replaced most of their iron rails with steel rails, new bridges were made of steel instead of iron, and whole new markets were created for steel in heavy industrial equipment and structures for buildings. In 1885, steel received an even greater boost when a new process was developed in Britain to improve the open-hearth furnace so it consistently produced highquality steel in large quantities from either high or low purity ores. Carnegie took another expensive gamble and replaced the

Bessemer furnaces in his plants with open-hearth furnaces, which lowered the cost of steel significantly.

Carnegie's ability to sense when new technology was applicable

—and to make the investments needed to apply the new technology

—had paid off again. In 1892, Carnegie consolidated all of his iron, steel, fabricating, bridge-building, and raw material companies into the Carnegie Steel Company. By 1898, the company produced more steel than Great Britain.

For the typical worker, laboring in the mill was hot and dangerous. Temperatures around the furnaces and the molten ingots were often high enough to be hazardous, accidents were frequent and brutal, and exposure to iron ore dust and fumes from the furnaces could damage a worker's lungs. Generally, plant managers did little to protect workers because a large labor pool promised a quick replacement for any worker who fell, became injured, or died. For the individual worker, however, working in the steel mill was a huge risk to personal safety.

In 1892, workers organized a strike at Carnegie Steel's Homestead Works, the only unionized plant in the company. A gunfight broke out between 300 Pinkerton guards brought in by the company and the strikers, resulting in the deaths of 3 guards and 10 strikers, with dozens of guards and strikers being injured. The National Guard broke up the strike, but labor disputes continued for many years, with the Homestead strike becoming a rallying point for organized labor.

In 1901, Morgan took over the Carnegie Steel Company after it encountered financial problems, in part caused by lingering effects of the financial Panic of 1893 and by the continuing labor disputes. Morgan used a voting trust to hide his organizations and activities by creating a small set of trustees to hold all of the stock in Carnegie Steel, controlling the company without being publicly accountable. Morgan then reorganized Carnegie Steel and merged it with other steel companies into the United States Steel

Corporation, allowing the company to successfully fight unionization and regulation until well after the Supreme Court declared the trusts illegal in 1913.

The other major financier of the Second Industrial Revolution was Rockefeller, who founded the Standard Oil Company to provide the oil for America's growing transportation network and in the process created a new kind of corporate structure, which would have a tremendous impact in American businesses. Standard Oil was the largest and most powerful company in America between 1880 and 1910. Initially, the company refined, shipped, and marketed oil for such products as medicine, lubricants, and most importantly, kerosene to light homes and factories.

By the 1860s, the oil industry consisted of four interrelated but independent industries: producers (to locate and drill for crude oil), refiners (to refine oil into chemicals), shippers, and distributors. Sensing a great financial opportunity if these industries could be incorporated into one company, Rockefeller merged his drilling and refining companies into the Standard Oil Company in June

1870. The new company began by producing 1,500 barrels of oil a day, making it the world's largest oil producer from the start.

Standard Oil then became active in distributing and marketing its products. Most people bought petroleum products through general merchandising stores like grocery, hardware, or drug stores. Oil products, however, were often shipped to markets in bulk tank cars, requiring complex networks of repackagers, distributors, and advertisers to manage the products in the marketplace.

Standard Oil set up an elaborate distribution and marketing network across the nation based on regional subsidiaries, thus gaining

control over much of the industry. By the 1880s, Standard Oil controlled most of the oil business from production to marketing —an arrangement that was entirely new for American corporations.

The Standard Oil Company was the first major company to alter its business practices because of lawsuits and government regulations. In building its corporate conglomerate, the company had integrated into one powerful organization all of the individual business steps required to produce, refine, distribute, and market oil, and then bought out its competitors, who had lost money when Standard Oil slashed prices in a way that any company not controlling every aspect of production could never afford.

Standard Oil also offered illegal bribes and kickbacks to various railroads and government officials to obtain preferential treatment.

To protect its monopoly by hiding its organizations and activities, the company adopted the voting trust, originally conceived by

Morgan, and formed the Standard Oil Trust. In 1911, using the Sherman Antitrust Act against large corporations for the first time, the U.S. Supreme Court declared in United States v. Standard Oil Company the voting trust, and other trust-like organizations, to be illegal, breaking Standard Oil into 70 separate companies.

Even though the company was justly criticized for its aggressive business practices, Standard Oil created order in the infant oil industry, defined the business processes needed by the industry, and prepared the industry to produce the most important chemical for the 20th century

—gasoline to fuel automobiles, airplanes, and boats. However, although the oil industry provides such important products as gasoline and petrochemicals (organic chemicals extracted from oil), the industry has also been a significant contributor to our environmental problems. Its production processes and its products can pollute the land, water, and air, as well as contribute to global warming. As usage of the petrochemicals has steadily increased, so has pollution.

Ford's contribution to the Second Industrial Revolution directly affected a large number of Americans on a daily basis by providing the automobiles that gave people true mobility. In 1908, the Ford Motor Company delivered the first Model T automobile to the country. It was marketed as a family car for the rapidly growing middle class rather than for the rich, so the car was priced at less than half the cost of other cars on the market, initially $825 but dropping to only $290 by 1924.

Using well established components for cars at that time, Ford standardized their design and production so that the Model T could be manufactured as it was carried on a conveyor down an assembly line where semi-skilled workers added components to each car that passed their workstation. Today, this approach seems obvious, but before it was introduced by Ford, teams of craftsmen made each car separately from components that had to be assembled by hand and customized to fit.

Ford's assembly line process revolutionized manufacturing, making all goods more affordable and therefore available to many more people, but it created a situation similar to the sweatshops of the 19th century because the typical worker's job became much more repetitive. The assembly line required workers to repetitively perform the same operations on each car as it went by their workstation, whether it was welding, painting, assembling, or testing, which reduced the amount of training workers needed because they no longer needed to understand any processes beyond their workstation.

Engineers could then optimize the work at each workstation to make it as simple as possible, which also made it a boring and tedious job for the worker. The work areas were often too hot or too cold, depending on the season, and were environmentally uncomfortable for laborers. Simplifying the work at a workstation also made the task of automating the assembly process much easier when automated equipment became available, ultimately causing many workers to lose their jobs.

As Ford's manufacturing plants grew in size, owners and executives became distant from their workers and their problems, leading to strong union organizing efforts to address worker grievances that eventually resulted in strikes and distrust on both sides. With help from the federal government, unions finally established a legal role in their dealings with Ford, representing labor's position on the many issues that affected Ford's workers.

Ford's assembly line process spread rapidly to other auto manufacturers and then to producers of many other products. So did the unions, representing other workers with their management problems. Eventually, the federal government passed such laws as the

National Labor Relations Act of 1935 and the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 that formalized the labor-management ground rules and established the National Labor Relations Board to mediate disputes. These developments created an entirely new environment for corporations after the Second Industrial Revolution.

The parade of new consumer goods brought to market during the 20th century has been phenomenal. New products for the home, most notably stoves, refrigerators, dishwashers, washing machines and dryers, and automatic furnaces and air conditioners, have transformed the home. New recreational products like telephones, cameras, radios, televisions, record players, and golf carts, have changed how people play. New products for industry, particularly synthetic materials, welding machines, testing machines, and office machines, have changed the workplace. The introduction of computers, telecommunications, and automation products has brought even more substantial change to Americans. All had their roots in the new technologies created during the first and second

phases of the Industrial Revolutions.

However, the rapid industrial growth is beginning to cause serious natural resource shortages and environmental problems.

Excessive use of the world's nonrenewable resources, particularly coal, oil, water, and ore deposits, will be a growing problem during the 21st century. Also, pollution of the land, water, and air by factories and the products they produce can create serious health problems. Creative solutions to these major challenges will be needed if America is to continue to grow.

There is no denying that the two revolutions, known collectively as the Industrial Revolution but actually composed of two significant phases, have prompted fundamental change in the lives of Americans, mostly for the better. The computer revolution that followed the Second Industrial Revolution is creating even more opportunities and more challenges, which should continue well into the 21st century.

References:

Clare, John D., ed., Industrial Revolution, 1994; Hunter, Louis C., A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1780-1930, vol. 2: Steam Power, 1986; Musson, A. E., and Eric Robinson, Science and Technology in the Industrial Revolution, 1989; Stearns,

Peter N., The Industrial Revolution in World History, 1993.

© 2006 ABC-CLIO. All rights reserved.