Lecture Notes

advertisement

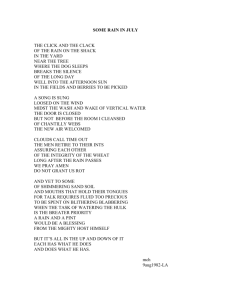

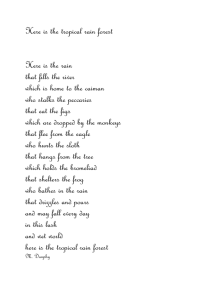

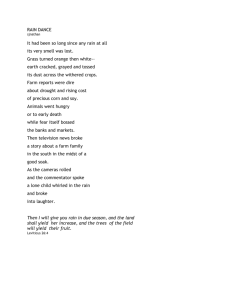

How to Read Literature like a Professor Lecture Notes “Every Trip is a Quest (Except when it’s not)” Aspects of a quest: (a) a quester (b) a place to go (c) a stated reason for going there (d) challenges and trials in route (e) a real reason to go there The real reason for the quest never involves the stated reason; in fact. More often than not the quester fails at the stated task. They go on the quest because of the stated reason, mistakenly believing that it is their real mission. We know, however, that their quest is educational. They don’t know about the subject that really matters: themselves. The real reason for a quest is always self-knowledge. Spider-Man example. “Nice to Eat with You: Acts of Communion” - Whenever people eat or drink together, it’s a communion (not in the religious sense). - In the real world, breaking bread together is an act of sharing and peace, since if you’re breaking bread you’re not breaking heads. - In literature, a meal that is successful portends a prosperous or fortunate future for community and understanding, whereas a meal that fails, or a dinner that turns ugly or doesn’t happen at all, portends the opposite. - Meals can serve as the catalyst for an act of bonding, camaraderie, or new-found understanding between characters. Discuss Their Eyes Were Watching God. “Nice to Eat You: Acts of Vampires” - Actual vampires: has a weird attractiveness to him, he’s alluring, dangerous, mysterious, and he tends to focus on beautiful, unmarried (in 19th century England this meant virginal) women. And when he gets them, he grows younger, more virile. Meanwhile, his victims become like him and begin to seek out their own victims. - By staling the girls’ innocence, he is actually taking away their “usefulness” (“marriageability”) - The Count Dracula saga has an agenda behind it beyond simply scaring us out of our wits: it deals with sex (body shame and unwholesome lust, seduction, temptation, danger) but it’s also about things other than literal vampirism: selfishness, exploitation, a refusal to accept the autonomy of other people. - Ghosts and doppelgangers (ghost doubles or evil twins) are about something besides themselves. In Hamlet, his father’s ghost is there to point out what is wrong in Denmark, and the ghost of Marley in A Christmas Carol is really a walking, clanking, moaning lesson in ethics for Scrooge. - In The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the hideous Edward Hyde exists to show that even a respectable man has a dark side- the duality of man. - - In Victorian England, the topic of sex was not allowed in literature so writers found a way to address sex without addressing it. But even today, when there are no limits on subject matter or treatment, writers still use ghosts, vampires, werewolves, and all manner of scary things to symbolize various aspects of our more common reality. Remember: ghosts and vampires are never about ghosts and vampires. Ghosts and vampires do not always have to appear in visible form (Turn of the Screw, “Daisy Miller”- copy pages 18-20 and read aloud with the kids). What vampirism really comes down to in its many forms is exploitation. Using other people to get what we want; denying someone else’s right to live in the face of our overwhelming demands; placing our desires, particularly our uglier ones, above the needs of another. Now that’s scary. “Now, Where Have I Seen Her Before?” - The more you read and the more you give thought to what you read, you will begin to see patterns, archetypes, recurrences. As with pictures among the dots, it’s a matter of learning to look. The more practice you have, the better you’ll become at recognizing the picture without connecting the dots. In literature, you need to learn not just to look but where to look and how to look. - Provide example from O’Brien’s Going After Cacciato. - Links to Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland- men fall down a hole and comment that the only way to get out is to fall back up- direct reference to the nonsensical world of Wonderland. - Sarkin Aung Wan- Sacajawea- guides white men west; she speaks the language they need to survive. - There’s only one story- all stories are built upon one another. - If you don’t see the references to other literature you are fine. The references just add to a deeper understanding of the work and can produce an aha! factor at recognizing links between works or, as some critics refer to it, a running dialogue between works- intertextuality. This intertextuality deepens and enriches the reading experience, brining multiple layers of meaning to the text. Just remember that the more you read the more you will see and recognize this ongoing dialogue; and before you know it, you’ll be asking yourself, “Now, where have I seen her before?” “When in Doubt, It’s from Shakespeare…” - If you look at any literary period between the eighteenth and twenty-first centuries, you’ll be amazed by the dominance of the Bard. He’s everywhere, in every literary form you can think of. And he’s never the same: every age and writer reinvents its own Shakespeare. - Traits the Bard made famous: astonishing disappearances and reappearances, characters in disguise (generally women dressed as men), the switch/mistaken identity (characters taking the place of another or pretending to be someone they’re not- their identity is misrepresented and not revealed until the final act of the play) - His lines continue to appear and reappear in all works of art: - - To thine own self be true, All the world’s a stage / And all the men and women merely players, Good night, sweet prince, / And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest! What’s in name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet By the pricking of my thumbs / Something wicked this way comes To be, or not to be, that is the question Writers quote what they’ve read or heard and turn to the Bard because his plays truly capture aspects of humanity. In fact, Harold Bloom contends that Shakespeare created the human. Readers love the plays, the characters, the witty repartee and, most importantly, the famous speeches. In all likelihood the majority of you will, at one time or another, find yourselves quoting Shakespeare. Shakespeare is everywhere and the majority of people have read at least one of his plays. We know Shakespeare, even if we haven’t read all of his works. “… Or the Bible” - Writers turn to the Bible, not because they are Christian and live within JudeoChristian tradition (though the majority of them are Christian), but because it was once the most widely read and referenced piece of literature. - Common images and themes from the Bible: garden, serpent, forbidden fruit, quest for knowledge, sibling rivalries, plagues, flood, parting of waters, loaves, fishes, forty days, betrayal, denial, slavery, the fall (loss of innocence), escape, fatted calves, milk and honey, resurrection, sacrifice, redemption, love. All universal themes that transcend religion. - Poetry is chock-full with quotations and situations from the Bible. - Beowulf is actually about the coming of Christianity into the old paganism of northern Germanic society- after being about a hero overcoming a villain. Grendel, the monster, is descended from the line of Cain, we’re told. - Watch out for irony- at times, authors will use Biblical references or images not to heighten continuities between the religious tradition and the contemporary moment but to illustrate a disparity or disruption. Sometimes these ironies are just a little too much for the public to fully understand (Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses). - Author’s also love to use Biblical names- Jacob, Jonah, Rebekah, Joseph, Mary, Hagar, etc. The naming of a character is never accidental. Garden of Eden: women tempting men and causing their fall, the apple as symbolic of an object of temptation, a serpent who tempts men to do evil, and a fall from innocence David and Goliath—overcoming overwhelming odds Jonah and the Whale—refusing to face a task and being “eaten” or overwhelmed by it anyway. Job: facing disasters not of the character’s making and not the character’s fault, suffers as a result, but remains steadfast The Flood: rain as a form of destruction; rainbow as a promise of restoration Christ figures (a later chapter): in 20th century, often used ironically - The Apocalypse—Four Horseman of the Apocalypse usher in the end of the world. Assign “Araby” for homework. “Hanseldee and Greteldum” - Because what readers know and read today varies dramatically from what it did twenty years ago, writers use kiddie literature for parallels, plot structures, and references because a good portion of the reading public can easily identify stories from their youth. - Fairy tales, like Shakespeare, the Bible, and mythology, belong to the one big story, and because, since we were old enough to be read to or propped up in front of a television, we’ve been living on that story, and on its fairy variants. Whenever fairy tales and their simplistic worldview crop up in connection with our complicated and morally ambiguous world, you can almost certainly plan on irony. - In the age of existentialism, the story of lost children has been all the rage. - We want strangeness in our stories, but we also want familiarity, too. And kiddie literature allows authors do this without sounding pretentious. o o o o o o o o o Hansel and Gretel: lost children trying to find their way home Peter Pan: refusing to grow up, lost boys, a girl-nurturer Little Red Riding Hood: See Vampires Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz: entering a world that doesn’t work rationally or operates under different rules, the Red Queen, the White Rabbit, the Cheshire Cat, the Wicked Witch of the West, the Wizard, who is a fraud Cinderella: orphaned girl abused by adopted family saved through supernatural intervention and by marrying a prince Snow White: Evil woman who brings death to an innocent—again, saved by heroic/princely character Sleeping Beauty: a girl becoming a woman, symbolically, the needle, blood=womanhood, the long sleep an avoidance of growing up and becoming a married woman, saved by, guess who, a prince who fights evil on her behalf. Evil Stepmothers, Queens, Rumpelstiltskin Prince Charming heroes who rescue women. (20th c. frequently switched—the women save the men—or used highly ironically) “It’s Greek to Me” - What we mean in speaking of “myth” in general is story, the ability of story to explain ourselves to ourselves in ways that physics, philosophy, mathematics, chemistry can’t. That explanation takes the shape of stories that are deeply engrained in our group memory, that shape our culture and are in turn shaped by it, that constitute a way of seeing by which we read the world and, ultimately, ourselves. Let’s say it this way: myth is a body of story that matters. - The Fall of Icarus: Daedalus, who crafted the wings, who knew how to get off of Crete and safely reach the mainland, and who in fact flew to safety; Icarus, the kid, the daredevil, failed to follow his father’s advice and plunged to his death. - His fall remains a source of enduring fascination for us and for art and literature. In it we see so much: the parental attempt to save the child and the grief at having failed, the cure that proves as deadly as the ailment, the youthful exuberance that leads to self-destruction, the clash between sober, adult wisdom and adolescent recklessness, and the terror involved in that headlong decent into the sea. Why reference the Greeks? Because by placing characters in situations where their nobility and courage are tested, they remind us that they are acting out some of the most basic, most primal patterns known to humans, exactly as Homer did all those centuries before. The need to protect one’s family: Hector; the need to maintain one’s dignity; the determination to remain faithful and to have faith: Penelope; the struggle to return home: Odysseus. Homer gives us four great struggles of the human being: with nature, with the divine, with other humans, and with ourselves. What is there, after all, against which we need to prove ourselves but those four things? “Never Stand Next to the Hero” - The hero’s best friend is at a higher risk. Usually they die and the hero is left with guilt and/or a need for revenge. - Remember: characters are not people. Even if they are based on actual people, they only the product of the writer’s and the reader’s imagination. The writer invents the character using memory, observations, and inventions and then their reader fills in the blanks using their own memories, observations, and inventions. - Round and Flat characters: Round characters are fully developed. Dynamic characters change. Flat characters are not fully developed (little is known about them). Static characters do not change. - Stories need both types. If all characters were round, it would be hard to figure out who the main character is and who to focus on. Also length would be an issue. “It’s More than Just Rain or Snow” - Even though weather does help in establishing setting, weather is never just weather; it’s never just rain. Rain prompts ancestral memories of the most profound sort. So water in great volume speaks to us at a very basic level of our being. And at times Noah is what it signifies. Remember, the flood might be a big eraser that destroys but, more importantly, it allows for a brand-new start. - Purposes of rain in literature: - (1) plot device- can force characters together or derive them apart - (2) atmospheric- rain can be more mysterious, murkier, more isolating than other weather conditions. Fog is good, too, of course. - (3) misery factor- rain has a higher wretchedness quotient than almost any other element of our environment. With a little rain and a bit of wind, you can die of hypothermia on the Fourth of July. - (4) the democratic element- Rain falls on the just and the unjust alike. - One of the paradoxes of rain is how clean it is coming down and how much mud it can make when it lands. If you want a character to be cleansed, symbolically, let him/her walk through the rain to get somewhere. They can be quite transformed when they get there. They can be less angry, less confused, more repentant. The stain that was upon them-figuratively- can be removed. On the other hand, if they fall down, they’ll be covered in mud and therefore more stained than before. - Rain has the ability- in literature- to cleanse people of their illusions and false ideals. It is also restorative (rain comes to the neglected land and with it life returns); this id chiefly because of its association with spring. Spring is the season not only of renewal but of hope, of new awakenings. Rain can bring the world back to life, to new growth, to the return of the green world. Keep in mind, however, that we have a less literary set of associations for rain that authors use for ironic purposes: it’s the source of chills, colds, pneumonia, and death. So watch out for the ironic factor. - Rain also mixes with the sun (another image of life) to produce rainbows. The main function of the image of the rainbow is to symbolize divine promise, peace between heaven and earth- it was God’s way of assuring Noah that he would never flood the earth again. Fog- signals confusion; suggests that people can’t see clearly, that matters under consideration are murky. And snow? Snow can mean as much as rain. Different but also the same. Snow is clean, stark, severe, warm (as an insulating blanket, paradoxically), inhospitable, inviting, playful, suffocating, filthy (with the passage of enough time). Just remember, whenever you start reading a poem or a story, always check the weather. - - “…More Than It’s Gonna Hurt You: Concerning Violence” - Violence is one of the most personal and even intimate acts between human beings, but it can also be cultural and societal in its implications. It can be symbolic, thematic, biblical, Shakespearean, Romantic, allegorical, transcendent. Violence in real life just is. - Read and discuss Frost’s “Out, Out-” p.88 - Two categories of violence in literature: the specific injury that authors cause characters to visit on one another or on themselves, and the narrative violence that causes characters harm in general. The first would include the usual range of behavior- shootings, stabbings, drownings, poisonings, bludgeonings, bombings, hit-and-run accidents, starvations. The second refers to death and suffering authors introduce into their work in the interest of plot advancement or thematic development and for which they, not their characters, are responsible (ex: Frost’s “Out, Out-”). - In works of literature, violence is symbolic action. (ex: Beloved. In Morrison’s classic novel, Sethe’s act of killing- drowning- her youngest daughter, Beloved, is so repugnant on a surface level that it is impossible to have sympathy for her; however, acute readers will realize that her action carries symbolic significance; we understand it not only as the literal action of a single, momentarily deranged woman but as an action that speaks for the experience of a race at a certain horrific moment in history, as a gesture explained by the whip scars on her back - that take the form of a tree, as the product of the sort of terrible choice that only characters in our great mythic stories- a Jocasta, a Madea- are driven to make. Sethe, in her own right, is a tragic heroine. She tries to drown her children because she is an escaped slave who is hiding out. When four white men ride up on horses, Sethe decides to take her children’s lives so they will not endure the humiliation of being slaves themselves. She only succeeds in killing her two-yearold daughter. The riders, in Sethe’s mind, are the Four Horsemen and they have come on The Last Day, the Day of Judgment). When dealing with what violence means, ask the following: What does this type of misfortune represent thematically? What famous or mythic death does this one resemble? Why this sort of violence and not some other? The answers may deal with psychological dilemmas, with spiritual crises, with historical or political concerns. Violence is everywhere in literature so when you see it, think about it. “Is that a symbol?” - Sure it is. If you think it is, it is. - Here’s the problem with symbols: people expect them to mean something. Not just any something, but one something in particular. It doesn’t work like that, though. In general, a symbol can’t be reduced to standing for one thing only. (A white flag? What does it mean? Peace? I surrender?) If they can, it’s not symbolic- it’s allegorical. A true symbol is likely not to be reduced to a single statement but will more likely involve a range of possible meanings and interpretations. - We want symbols to mean one thing and one thing only, because that would be convenient, easy. But that handiness would result in a huge loss: the novel would cease to be what it is, a network of meanings and significations that permits a nearly limitless range of possible interpretations. Each of us brings a different perspective to a piece of literature so each of us will see and interpret things differently. We all bring a mix of previous readings, personal history, gender, race, class, faith, social involvement, and philosophical inclination. And this is the beauty of literature- it’s open for interpretation. If we want to figure out what a symbol might mean, we have to use a variety of tools on it: questions, experience, and preexisting knowledge. - The other problem with symbols is that many readers expect them to be objects and images rather than events or actions. However, action can be symbolic too. - Read and discuss the speaker’s “moment of decision” in Frost’s “The Road Not Taken”- p. 106 - When discussing symbolism, ask questions of the text: What’s the writer doing with this image, this object, this act? What possibilities are suggested by the movement of the narrative or lyric? What does it feel like it’s doing? - Symbolism is all about feeling. If you feel it means something, then it probably does- to you. Now, the trick is finding out what. And for that, you need to search within yourself. For the meaning of a symbol is in the eye of the reader. “It’s All Political” - Some “political” writing does not withstand the test of time because it becomes too “preachy” and focuses on only one aspect pf politics. Good political writing engages the realities of its world- it thinks about human problems, including those in the social and political realm, as well as addressing the rights of persons and the wrongs of those in power. - EX: Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. The story is actually a social commentary against a popular theory that was afoot during Dickens’s time. Thomas Malthus argued that in helping the poor or in increasing food production to feed more people would, in fact, encourage an increase in the number of the impoverished, who would, among other things, simply procreate faster to take advantage of all that surplus good. Dickens caricatures this Malthusian thinking in Scrooge’s insistence that he wants nothing to do with the poor. In fact, during the course of the novel, some of Scrooge’s pronouncements echo those from Malthus and his Victorian descendants. The story is meant to change us and through us change society. The tale attacks one way of thinking about our social responsibilities and valorizes another. - Nearly all writing is political on some level; you could argue that the role of the individual is always politically charged, that matters of autonomy and free will and self-determination always drag in the larger society, if only imaginatively. - Writers and works must engage with their own specific period in ways that can be called political. Writers tend to be men and women who are interested in the world around them. That world contains many things, and on the level of society, part of what it contains is the political reality of the time- power structures, relations among classes (Marxist theory), issues of justice and rights, interactions between sexes (Feminist) and among various racial and ethnic constituencies (African American Theory). - Knowing a little something about the social and political milieu (climate) out of which a writer creates can only help us understand his/her work, not because that milieu (setting) controls their thinking but because that is the world they engage in when they sit down to write. - Read “Rip Van Winkle” “Yes, She’s a Christ Figure, Too” - Culture is so influenced by its dominant religious systems that whether a writer adheres to the beliefs or not, the values and principals of those religions will inevitably inform the literary work, and since we live in a Christian culture, the majority of the writing will incorporate some aspect of the Christian faith, primarily imagery related to Christ himself. - As you’re reading a story or a poem, religious knowledge is helpful, although religious belief, if too tightly held, can be a problem. We want to be able to identify features in stories and see how they are being used; in other words, we want to be analytical, not judgmental. When looking for aspects related to Christ or Christianity, it’s the symbolic level we’re interested in, not the literal. Remember, though, that no literary Christ figure can ever be as pure, as perfect, as divine as Jesus Christ. Here, one does well to remember that writing literature is an exercise of the imagination. And so is reading it. - Christ figures are where you find them, and as you find them. If the indicators are there, then there is some basis for drawing the conclusion. Here is a quick, though by no means definitive list, of indicators that a character (yes, even a female one) just might be a Christ figure: 1) crucified, wounds in the hands, feet, side, head 2) in agony 3) self-sacrificing 4) good with children 5) good with loaves, fishes, water, wine 6) thirty-three years of age when last seen 7) employed as a carpenter 8) known to use humble modes of transportation, feet or donkeys preferred 9) believed to have walked on water 10) often portrayed with arms outstretched 11) known to have spent time alone in the wilderness 12) believed to have had a confrontation with the devil, possibly tempted 13) last seen in the company of thieves 14) creator of many aphorisms and parables 15) buried, but arose on the third day 16) had disciples, twelve at first, although not all equally devoted 17) very forgiving 18) came to redeem an unworthy world 19) unmarried, preferably celibate - Why are there Christ figures? Probably the writer wants to make a certain point; perhaps the parallel deepens our sense of the character’s sacrifice if we see it as somehow similar to the greatest sacrifice we know of. Or maybe it has to do with redemption, or hope, or miracle (thematic elements). “Flights of Fancy” - Man has always held a fascination with flight - Flight was one of the temptations of Christ- that is why it’s considered “witchcraft” - In general, flying is freedom; freedom not only from specific circumstances but from those more general burdens that tie us down. It’s escape, the flight of imagination. - Flight, literally and figuratively, can mean freedom, escape, return to home, largeness of spirit, love. What it boils down to is flight is freedom. It does not need to be a physical flight; fleeing can also be seen as flight, such as when Inman, in Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, flees from the war in order to return home to his love Ada. He has become disillusioned with the war and feels the only way he can be redeemed is to return home. On his journey home there are constant references to flight and birds. - As with everything else in literature, however, remember that irony trumps everything. Angela Carter’s example p.128 Often in literature the freeing of the spirit is seen in terms of flight An interrupted flight is generally a bad thing Read “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” “It’s All About Sex…” a. Female symbols: chalice, Holy Grail, bowls, rolling landscapes, empty vessels waiting to be filled, tunnels, images of fertility b. Male symbols: blades, tall buildings c. Why use symbols? - Before mid 20th century, coded sex avoided censorship - Can function on multiple levels - Can be more intense than literal descriptions “…Except Sex” - When authors write directly about sex, they’re writing about something else, such as sacrifice, submission, rebellion, domination, supplication, enlightenment, etc. “If She Comes Up, It’s Baptism” - Baptism is a symbolic death (of the old self) and rebirth as a new individual. - While rain can be restorative and cleansing, it generally lacks the specific baptismal associations of submersions. And the thing with baptism is, the characters have to be ready to receive it. - Drowning is symbolic baptism. If the character comes back up, he/she is symbolically reborn. Drowning on purpose can also represent a form of rebirth, a choosing to enter a new, different life, leaving an old one behind. - Every drowning serves its own purpose: character revelation, thematic development of violence or failure or guilt, plot complication or denouement) - Traveling on water- rivers, oceans- can symbolically represent baptism (i.e. young man sails away from a known world, dies out of one existence and comes back a new person, hence rebirth). Rivers can also represent the River Styx, the mythological river separating the world from the Underworld; another form of transformation, passing from life into death. - There’s also rebirth/baptism when a character is renamed. - Baptism by fire- fire can also be seen as cleansing and restorative- it burns away the old life, singes perceptions, and offers rebirth and new insights (mythologicalthe phoenix who is “reborn out of its ashes.”) EX: Fahrenheit 451- the bomb, explosion destroys the old world and allows for a new, better world to emerge; Beatty attains salvation through fire- he becomes cleansed of his sin. “Geography Matters” Pay attention to directions in literature. North (up)- Heaven; purity; enlightenment, clarity, hope; characters may see clearly for the first time; issues become resolved, heightened sense of self; looks down below and sees problems but can also see solutions to problems- old and new. Think about what is up: snow, ice, purity, thin air, clear views, isolation, life, death. South (down)- Hell; characters go south so they can run amok; journey into the self; psyche; the heart of darkness; despair, things become foggy and unclear; loss and confusion; encounters with the subconscious. Think about what is low: swamps, crowds, fog, darkness, fields, heat, unpleasantness, people, life, death. East- rebirth; renewal; life (sun rises in the east) West- death; despair; desolation (sun sets in the west) What does it mean to the novel that its landscape is high or low, steep or shallow, flat or sunken? Why did this character die on a mountain top, that one on the savannah? Literary geography is typically about humans inhabiting spaces, and at the same time the spaces that inhabit humans. - Geography is setting, but it’s also (or can be) psychology, attitude, finance, industry- anything that place can forge in the people who live there. - Geography can also define or develop character - Geography can be character (Going After Cacciato- the land is destroyed; the squad pours its fear and anger at the land by blowing up an abandoned village: if they can’t overcome the larger geography, they can at least express their range against this small portion of it) - It can be significant to the plot- the story would be different if it didn’t happen at a certain place. “…So Does Season” Always pay attention to the seasons as well. Spring: youth, rebirth, life, fertility, happiness, growth, resurrection (Easter) Summer: passion and love, adulthood, coming-of-age, maturity, youth, fulfillment Fall: decline, middle age, tiredness, but also harvest (depends how it is used) Winter: death, desolation, resentment, old age, hibernation, lack of growth, punishment - The ancient Romans named the first month of our calendar after Janus, the god of two faces, the month of January looking back into the year gone by and forward in the one to come. - Nearly every early mythology, at least those originating in temperate zones where seasons change, had a story to explain the seasonal changes (p.181-182; Persephone and Hades) - Irony trumps everything: “April is the cruelest month” from Elliot’s “The Wasteland” “Marked for Greatness” - look at physical imperfection in symbolic terms; these marks mirror moral, emotional, or psychological scars or imperfections. - In many stories, heroes are marked in some visible way. They may be scarred or lamed or wounded or painted or born with a short leg- there is some mark that sets them apart from other characters. - Blindness can be a mark for greatness (it also signifies atonement; guilt) - - Physical imperfection, when caused by social imperfection, often reflects not only the damage inside the individual, but what is wrong with the culture that causes such damage. Monsters: (a) Frankenstein’s monster: created through no fault of their own; the maker is the real monster. (b) Faust: bargains with the devil in exchange for his soul (c) Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: The Romantics argues about the duality of human nature- that in each of us there is a dark side, a monstrous Other just waiting for its chance to escape. (d) Quasimodo, Beauty and the Beast: ugly on the outside, beautiful on the inside. The physical deformity reflects the opposite of the truth. “He’s Blind for a Reason, You Know” - Physical blindness mirrors psychological, moral, intellectual blindness. The author obviously wants to emphasize other levels of sight and blindness beyond the physical. - Sometimes the blindness is ironic; the blind see and sighted are blind (Oedipushe was “blind to the truth” while Tiersias (who is blind) sees everything) - Many times blindness is metaphorical, a failure to see- reality, love, truth - Darkness=blindness, light=sight “It’s Never Just Heart Disease…And Rarely Just Illness” - The heart is the symbolic repository of emotion in literature; when we fall in love we say we feel it in our hearts; when we lose a loved one, we feel heartbroken; when overwhelmed with strong emotions, we feel our hearts are about to burst. - Writer’s use heart ailments as a kind of short hand for characterization. A “heart problem” can really mean bad love, loneliness, cruelty, disloyalty, cowardice, or a lack of determination. Socially, it may stand for these matters on a larger scale, or for something seriously amiss at the heart of things (Heart of Darkness). If a character has a heart problem, ask yourself what the real problem is. - Authors use illnesses because they remain frightening and mysterious. In the past, people sickened and died for no discernable reason except that they “fell ill.” - With diseases in literature, not all are created equally. Cholera was more widespread than TB, but because of how nasty it is, writers instead focused on TB because it is a wasting away disease- they can use it literally or figuratively. - An illness should be mysterious in origin. - It should have strong symbolic or metaphorical possibilities: (a) Tuberculosis- a wasting away disease (b) Physical paralysis can mirror moral, social, spiritual, intellectual, political paralysis (c) Plague: divine wrath; suffering on a large scale; the isolation and despair created by wholesale destruction (d) Malaria: literally means “bad air”- great metaphorical possibilities. (e) Venereal disease: reflects immorality or innocence, when the innocent suffer because of another’s immorality; men’s exploitation of women. - For our generation the disease of choice is AIDS. Just think about it and it becomes evidently clear why others would choose this disease. “Don’t Read with Your Eyes” - When reading, try not to read only from your own fixed position in the Year of Our Lord two thousand and some. Instead try to find a reading perspective that allows for sympathy with the historical moment of the story that understands the text as having been written against its own social, historical, cultural, and personal background. - We don’t have to accept the values of another culture to sympathetically step into a story and recognize the universal qualities present there. “It’s My Symbol and I’ll Cry if I Want To” - Review this chapter on your own. Most of what you need about symbolism comes from CH. 12 “Is He Serious? And Other Ironies” - The absolute rule of literature: Irony trumps everything. - Ex. Waiting for Godot- journeys, quests, self-knowledge turned on its head. Two men by the side of a road they never take and which never brings anything interesting their way. - Irony chiefly involves a deflection from expectation. Authors play with our preconceived notions and turn them upside down and inside out in order to throw us off and bring something to our attention. - Irony doesn’t work for everyone. It’s difficult to warm to, hard for some to recognize which causes all sorts of problems. (Ex: A Clockwork Orange- Alex as a Christ figure- has followers, betrayed by one of them, tempted by the devil, has his free will taken away which is the hallmark of humanity- Alex’s sacrifice makes people bear witness to the inhuman treatment of the “Ludovico Technique.” Alex, unwittingly, sacrifices himself so that others will live).