Socialism Overview Essay.doc - Dorman-Data

advertisement

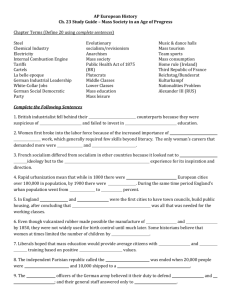

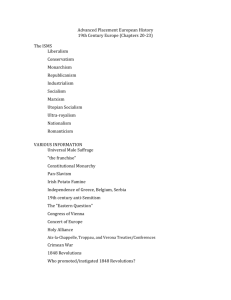

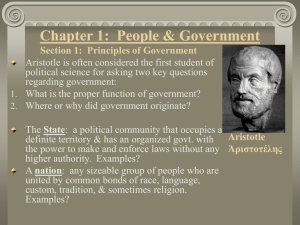

socialism Socialism is a social and governmental system, based on equality and social and economic justice, that requires government intervention in economic affairs. The state, rather than individual or market forces, owns and controls the means of production, distribution, and exchange. Socialism refers to both political doctrines and the political movement and system in which the doctrines are enacted. There are various forms of socialism, but all stress the need for revolutionary changes to redress what are believed to be moral flaws in capitalism. Socialists believe that capitalism was intended to satisfy people's needs and wants at a price, which along with paid interest and the profit motive, is immoral. Socialism stems from democracy, as the ideal of political equality is extended to economic equality. In theory, socialism is the first step toward communism. However, socialism differs from communism because it is based on democracy and ethical values and can allow for private ownership. Some historians trace the roots of socialism to the rise of philosophy in Greece. Social organization and the need to cooperate have always existed, and Hellenistic philosophy was concerned with the problems of society and citizenship. Christian morality developed from Hellenistic philosophy, and that morality encompassed economic issues. For example, the New Testament, which became the prevailing ethical code of Western civilization, included laws against usury, or excessive interest. The writings of Aristotle, as well as the Bible, show a belief that humans are entitled only to the property that they have created by their labor—a protosocialist idea. The roots of modern socialism are in revolutions in France and England. The French Revolution was the largest lower-class revolt in history, as the Third Estate, which included bourgeoisie and peasants, rebelled under the banner of "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" against the established societal, economic, and political structure of the ancien régime. The revolution progressed into a struggle for political and economic equality, as the depressed state of the French economy spread misery equally among the peasants. The Industrial Revolution in England started with the hope that the increased industrial development of a nation would lead to economic equality but instead led to the exploitation of workers and the concentration of wealth in the industrial capitalists. Those factors led to the utopian socialist movements in France and Great Britain during the early 19th century. For example, Henri de Saint-Simon believed that the social system of France before the French Revolution was not appropriate for the new age. Science had taken the place of the Catholic Church in the new era, and industry should take the place of lineage in determining social position. Saint-Simon's followers were among the first who viewed private property and capitalism as incompatible with the new system, and they argued against the hereditary transfer of wealth. Saint-Simon and his followers were influential on the early writing of Karl Marx. Charles Fourier was another early philosopher of utopian socialism who advocated the reconstruction of society into cooperative communities where work was distributed on a rotating basis among all members. Fourier advocated a scientific view of society, and his economic ideas are considered to be the forerunners of the ideas of Marx. He explained his ideas when he published Theory of Social Organization in 1820, which inspired utopian communities, including Brook Farm in Massachusetts during the 1840s. Another utopian socialist, Robert Owen, believed that cooperative living could solve the problems of unemployment and poverty. He established New Harmony in 1825 as a utopian community based on the principles of shared work, complete equality, and communal property without a religious basis. New Harmony failed and was disbanded in 1827. During the 1830s, Chartism appeared in Great Britain as the first working-class movement in the world. William Lovett drafted the Chartist People's petition (1838), which demanded reform for working conditions in Great Britain. At around the same time, Louis Blanc advocated radical social and political reforms in France. Blanc outlined his view for an ideal socialist state in The Organization of Labor, published in 1840. Later, Blanc became a leader in the socialist movement that led to the Revolutions of 1848. During this period, the anarchist movement emerged, led by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who supported some socialist principles by attacking the private property of the bourgeoisie. Marx and Friedrich Engels published the Communist Manifesto (1848)—written before the Revolutions of 1848—which outlined Marxism and became the basis for communism, the most radical form of socialism, by arguing that class struggle was the dynamic force in history and that a proletarian revolution was imminent. The Revolutions of 1848 took on some characteristics of a socialist workers' revolution, as workers marched in the streets of Vienna and Paris demanding more rights and unemployment protection. The revolutions were prompted by economic depression, political discontent, and nationalism, but they caused a backlash among the conservative monarchs. Although largely unsuccessful, the Revolutions of 1848 helped to inspire further workers' struggles during the late 19th century. In support of some aspects of Chartism and in response to the revolutions, many believed that the combination of equality and communality brought by socialism and the Christian principles of peace and love would produce an ideal society. However, Christian socialism was not as adamant as other forms of socialism because its leaders, Charles Kingsley and F. D. Maurice, were more intent on Christianizing socialism than socializing the world. The first attempt at an international organization of labor, the First International, was organized in 1864 but had its roots in the Revolutions of 1848. Marx and Engels led the First International on the idea of class struggle, the inevitability of the collapse of capitalism, the need for a workers' revolution, and the abolishment of private property. The organization attracted a number of anticapitalist leaders. During the late 19th century, socialist organizations continued to develop. As a move toward social democracy in the German states, the German Social Democratic Party was founded in 1869 by August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht. The party began with a demand for government intervention in the relations between capital and labor, and it later demanded a structure of federalism for Germany that included an end to class rule. After German unification, however, the government under Otto von Bismarck began passing antisocialist laws in 1878. Socialist leaders were not allowed to organize or have newspapers, and many were sent into exile. Also during this period, the Fabian Society was established in the United Kingdom in 1883. The organization was based on Marxist revisionism, as its members did not believe in the need or the imminence of violent revolution. Developing from socialist parties and movements throughout the world, the Second International began in 1889 with the hope of coordinating a worldwide struggle against capitalism. The Second International split into revolutionaries and revisionists before it ended at the start of World War I. Syndicalism also emerged during the early 20th century; its proponents advised workers to overthrow the government by strikes. Based on the principles of Marxism and anarchism, syndicalism advocated the replacement of the government by a series of local cooperative associations. During this time, the Socialist Party of America emerged and reached its height when presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs received 6% of the popular vote in 1912. At the same time, the guild socialism movement emerged in the United Kingdom with the goal of abolishing capitalism and establishing workers' guilds to control industry with the government's approval. Guild socialism coincided with the rise of organized labor but died out soon after World War I. The development of socialism reached its peak of radicalism with the Bolshevik Party, created by Vladimir Lenin during the years before the Russian Revolution of 1917. The development of Lenin's political thought borrowed heavily from Marxist revolutionary principles, but Marxism-Leninism included the belief that a group of dedicated revolutionaries must control, and complete, the revolution. This ideological departure led to the development of communism. During the years following World War II, socialism developed in different ways. In Africa, countries slowly began to gain independence from their colonizers. African countries attempted to wean themselves from Western trade by developing government-controlled economies. African socialism was seen as compatible with the rise of nationalism on the continent, as many saw capitalism as an extension of colonialism. With the decline of communism, however, many countries moved toward a more open economy. The latest and most revised form of socialism is market socialism. In this system, the state maintains ownership of economic enterprises but allows market forces, rather than planning, to guide the economy. The system emerged in eastern Europe during the 1960s and 1970s. Western socialism also emerged during the 20th century, as such countries as Sweden and Great Britain adopted a social safety net, guaranteeing a minimal standard of living for all citizens. Unlike the Marxist prediction, those changes were made through a parliamentarian government, not through violent revolution. At the dawn of the 21st century, socialism continues to change. In the philosophy of Marx, socialism that provides equality without a revolution has not been successful. However, many of the basic tenets of socialist thought still hold sway. Though no longer considered revolutionary, many people believe in the right to a minimal standard of living that includes health care and education. The redistribution of wealth through taxes and government programs in capitalist countries remains socialism's lasting effect on world history. References: Bauman, Zygmunt, Socialism: The Active Utopia, 1976; Davis, Horace B., Nationalism and Socialism, 1967; Lichtheim, George, A Short History of Socialism, 1970; Taylor, Keith, The Political Ideas of the Utopian Socialists, 1982. "socialism." World History: The Modern Era. 2007. ABC-CLIO. 15 May 2007 <http://www.worldhistory.abc-clio.com>.